Circumventing the China Extradition Conundrum: Relying on Deportation to Return Chinese Fugitives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

002170196E1c16a28b910f.Pdf

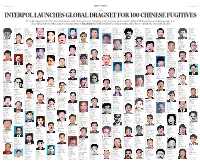

6 THURSDAY, APRIL 23, 2015 DOCUMENT CHINA DAILY 7 JUSTICE INTERPOL LAUNCHES GLOBAL DRAGNET FOR 100 CHINESE FUGITIVES It’s called Operation Sky Net. Amid the nation’s intensifying antigraft campaign, arrest warrants were issued by Interpol China for former State employees and others suspected of a wide range of corrupt practices. China Daily was authorized by the Chinese justice authorities to publish the information below. Language spoken: Liu Xu Charges: Place of birth: Anhui property and goods Language spoken: Zeng Ziheng He Jian Qiu Gengmin Wang Qingwei Wang Linjuan Chinese, English Sex: Male Embezzlement Language spoken: of another party by Chinese Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Female Charges: Date of birth: Chinese, English fraud Charges: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Accepting bribes 07/02/1984 Charges: Embezzlement Embezzlement 15/07/1971 14/11/1965 15/05/1962 03/01/1972 17/07/1980 Place of birth: Beijing Place of birth: Henan Language spoken: Place of birth: Place of birth: Place of birth: Language spoken: Language spoken: Chinese Zhejiang Jinan, Shandong Jilin Chinese, English Chinese Charges: Graft Language spoken: Language spoken: Language spoken: Charges: Corruption Charges: Chinese Chinese, English Chinese Embezzlement Charges: Contract Charges: Commits Charges: fraud, and flight of fraud by means of a Misappropriation of Yang Xiuzhu 25/11/1945 Place of birth: Chinese Zhang Liping capital contribution Chu Shilin letter of credit Dai Xuemin public funds Sex: Female -

Christian Women and the Making of a Modern Chinese Family: an Exploration of Nü Duo 女鐸, 1912–1951

Christian Women and the Making of a Modern Chinese Family: an Exploration of Nü duo 女鐸, 1912–1951 Zhou Yun A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University February 2019 © Copyright by Zhou Yun 2019 All Rights Reserved Except where otherwise acknowledged, this thesis is my own original work. Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Benjamin Penny for his valuable suggestions and constant patience throughout my five years at The Australian National University (ANU). His invitation to study for a Doctorate at Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW) not only made this project possible but also kindled my academic pursuit of the history of Christianity. Coming from a research background of contemporary Christian movements among diaspora Chinese, I realise that an appreciation of the present cannot be fully achieved without a thorough study of the past. I was very grateful to be given the opportunity to research the Republican era and in particular the development of Christianity among Chinese women. I wish to thank my two co-advisers—Dr. Wei Shuge and Dr. Zhu Yujie—for their time and guidance. Shuge’s advice has been especially helpful in the development of my thesis. Her honest critiques and insightful suggestions demonstrated how to conduct conscientious scholarship. I would also like to extend my thanks to friends and colleagues who helped me with my research in various ways. Special thanks to Dr. Caroline Stevenson for her great proof reading skills and Dr. Paul Farrelly for his time in checking the revised parts of my thesis. -

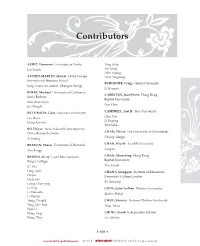

Contributors.Indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM F-479 /203/BER00069/Work/Indd/%20Backmatter

02_Contributors.indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM f-479 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter Contributors AUBIÉ, Hermann University of Turku Yang Jiang Liu Xiaobo Yao Ming Zhao Ziyang AUSTIN-MARTIN, Marcel China Europe Zhou Youguang International Business School BURGDOFF, Craig Capital University Jiang Zemin (co-author: Zhengxu Wang) Li Hongzhi BERRY, Michael University of California, CABESTAN, Jean-Pierre Hong Kong Santa Barbara Baptist University Hou Hsiao-hsien Lien Chan Jia Zhangke CAMPBELL, Joel R. Troy University BETTINSON, Gary Lancaster University Chen Yun Lee, Bruce Li Keqiang Wong Kar-wai Wen Jiabao BO Zhiyue New Zealand Contemporary CHAN, Felicia The University of Manchester China Research Centre Cheung, Maggie Xi Jinping BRESLIN, Shaun University of Warwick CHAN, Hiu M. Cardiff University Zhu Rongji Gong Li BROWN, Kerry Lau China Institute, CHAN, Shun-hing Hong Kong King’s College Baptist University Bo Yibo Zen, Joseph Fang Lizhi CHANG Xiangqun Institute of Education, Hu Jia University College London Hu Jintao Fei Xiaotong Leung Chun-ying Li Peng CHEN, Julie Yu-Wen Palacky University Li Xiannian Kadeer, Rebiya Li Xiaolin Tsang, Donald CHEN, Szu-wei National Taiwan University Tung Chee-hwa Teng, Teresa Wan Li Wang Yang CHING, Frank Independent Scholar Wang Zhen Lee, Martin • 569 • www.berkshirepublishing.com © 2015 Berkshire Publishing grouP, all rights reserved. 02_Contributors.indd Page 570 9/22/15 12:09 PM f-500 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter • Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography • Volume 4 • COHEN, Jerome A. New -

Article on the Un Convention Against Transnational

ARTICLE ON THE UN CONVENTION AGAINST TRANSNATIONAL ORGANIZED CRIME AND CONVENTION AGAINST CORRUPTION IN CHINA: DOMESTIC EFFORTS AND INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION Shang Haowen Huang Gui Table of Contents I.INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 85 II.THE UNTOC AND THE UNCAC IN CHINA: FROM ACCEPTANCE TO IMPLEMENTATION ................................................................................. 90 A. Challenges in Bolstering Anticorruption Cooperation ................. 90 B. Overriding Principles of Combating Corruption .......................... 95 1. Good Governance ................................................................... 95 2. Rule of Law ........................................................................... 102 III.DOMESTIC ANTI-CORRUPTION LEGAL FRAMEWORK .............................. 106 A. Overview of Updates in Chinese Anticorruption Legal Framework ..................................................................................................... 107 B. To Promise and Propose Giving a Bribe Was First Stipulated in the Criminal Law ........................................................................ 109 C. The Corruption Involving Foreign and International Officials Could Be Cracked down on by Criminal Law ........................... 111 D. The Corruption Involving Legal Person and its Liabilities ........ 112 IV.INTERNATIONAL ANTICORRUPTION COOPERATION PRACTICE ............... 115 A. The Domestic Legal Basis of International Anticorruption -

Paper by Professor ZHAO Bingzhi, Dean, College for Criminal Law

Paper by Professor ZHAO Bingzhi, Dean, College for Criminal Law Science and School of Law, Beijing Normal University and President, Criminal Law Research Committee, China Law Society, Mainland China Criminal Legality in Mainland China’s 30 Years of Reform and Opening-up — Perspective from a Number of Typical Cases (Translation of original speech in Chinese) Table of Contents Preamble I. Outline of the criminal legality prior to the promulgation and implementation of the 1997 Penal Code (1978-1997) (I) Lin Biao & Jiang Qing Counter-revolutionary Group Case (II) Han Kun Bribe-taking Case (III) Jiang Aizhen Intentional Homicide Case (IV) December Eighth Karamai City (Xinjiang) Major Liability Incident & Negligence of Duty Case II. Outline of the criminal legality subsequent to the promulgation and implementation of the 1997 Penal Code (1997-2008) (I) Zhang Ziqiang Case (II) Gong Jianping Football “Black Whistle” Case (III) Zheng Xiaoyu Bribe-taking & Negligence of Duty Case (IV) Xu Ting Theft Case (V) Several Typical Cases with Criminal Fled Away (Yu Zhendong Case, Hu Xing Case and Lai Changxing Case) Conclusion Preamble The reform and opening-up cause of China has witnessed a 30-year splendid and brilliant course since the third plenary session of the 11th Central Committee in December 1978. The 30 years of reform and opening-up was accompanied with the 30 years of hardships and explorations, the 30 years of fluctuations and transitions and the 30 years of advancements within each passing day. We have, during these 30 years of reform and opening-up, gone through earthshaking social developments and changes and have acquired spectacular achievements to which worldwide attention was drawn. -

The Prevention and Control of Economic Crime in China

The Prevention and Control of Economic Crime in China: A Critical Analysis of the Law and its Administration Enze Liu Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Advanced Legal Studies School of Advanced Study, University of London September 2017 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis represents my own work. Where information has been used they have been duly acknowledged. Signature: …………………………. Date: ………………………………. 2 Abstract Economic crime and corruption has been an issue throughout Chinese history. While there may be scope for discussion as to the significance of public confidence in the integrity of a government, in practical terms the government of China has had to focus attention on maintaining confidence in its integrity as an issue for stability. Since the establishment of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its assumption of power and in particular after the ‘Opening’ of the Chinese economy, abusive conduct on the part of those in positions of privilege, primarily in governmental organisations, has arguably reached an unprecedented level. In turn, this is impeding development as far as it undermines public confidence, accelerates jealousy and forges an even wider gap between rich and poor, thereby threatening the stability and security of civil societies. More importantly, these abuses undermine the reputation of the CCP and the government. China naturally consider this as of key significance in attracting foreign investment and assuming its leading role in the world economy. While there have been many attempts to curb economic crime, the traditional capabilities of the law and particularly the criminal justice system have in general terms been found to be inadequate. -

A Sporting Ambition P.26

world: S. AFRICAN PRESIDENT INTERVIEW P.18 | NATION: A SPORTING AMBITION P.26 VOL.57 NO.50 DECEMBER 11, 2014 WWW.BJREVIEW.COM TARGET IN FOCUS China aims to intensify anti-corruption efforts through international cooperation RMB6.00 USD1.70 AUD3.00 GBP1.20 CAD2.60 CHF2.60 JPY188 邮发代号2-922·国内统一刊号:CN11-1576/G2 VOL.57 NO.50 DECEMBER 11, 2014 CONTENTS 38 Ecologically Invested EDITOR’S DESK A conversation with China’s top 02 No Place to Hide eco-business innovator THIS WEEK 40 Market Watch CULTURE COVER STORY 44 The Sound of Hunan An operatic revival takes place WORLD 22 The Korean Quandary FORUM Pyongyang-Moscow meeting under 46 Statesman to Statesman the microscope Veteran German politician offers COVER STORY appraisal of Xi’s new book NATION 14 26 Not a Spectator Sport Coming Together Against Corruption EXPAT’S EYE Giving promising sector a sporting China sniffs out graft suspects abroad 48 Right on Track chance In defense of China’s transportation system BUSINESS 34 Calling Private Investors WORLD Will relaxed policy open investment floodgates? P.20 | Necessary Negotiations 36 Green Desert Seeking a solution to Iran nuclear issue From arid wasteland to fertile wonderland BUSINESS P.32 | Safeguarding Deposits Protecting interests of China’s banking customers WORLD P.18 | A Multifaceted Friendship South African president on collaboration ©2014 Beijing Review, all rights reserved. with China www.bjreview.com Follow us on BREAKING NEWS » SCAN ME » Using a QR code reader Beijing Review (ISSN 1000-9140) is published weekly for US$64.00 per year by Cypress Books, 360 Swift Avenue, Suite 48, South San Francisco, CA 94080, Periodical Postage Paid at South San Francisco, CA 94080. -

1 Annotated Bibliography of Liu Xiaobo's Texts in Chronological Order

1 Annotated Bibliography of Liu Xiaobo’s Texts in Chronological Order Year Chinese Title English Title Category 04/1984 艺术直觉 On Artistic Intuition 关系学院 学 1 1984 庄子 On Zhuangzi 社科学战线 05/1985 和冲突 – 中西美意的差别 Harmony and Conflicts – Differences between Chinese 京师范大学 and Western Aesthetics 学 07/1985 味觉说 Theory of Taste 科知 Early 1986 种的美思潮 – 徐星陈村索拉的 A New Aesthetic Trend – Remarks Inspired by the Works 文学 2 部作谈起 of Xu Xing, Chen Cun and Liu Suola (1986:3) 04/1986 无法回避的思 – 几部关知子的小说 Unavoidable Reflection – Contemplating Stories on 中 / MA 谈起 Intellectuals (EN 94) Thesis 03/10/1986 机,时期文学面临机 Crisis! New Era’s Literature is Facing a Crisis (FR) 深圳青 10/1986 李厚对 – Dialogue with Li Zehou (1) 中 1986 On Solitude (EN) 家 1988:2 1 th Zhuangzi was a Chinese Daoist thinker who lived around the 4 century BC during the Warring States period, when the Hundred Schools of Thought flourished. 2 Shanghai writer Chen Cun (1954-) and Beijing writers Liu Suola (1955-) and Xu Xing (1956-) who expressed contempt for the formal education of the mid-1980s and its pretention. Liu Xiaobo responded to a conservative attack on 'superfluous people' by defending these three writers who were popular in 1985 and who would be also attacked in 1990 as “rebellious aristocrats” whose works displayed a “liumang mentality.” He wrote a positive interpretation of their way of “ridiculing the sacred, the lofty and commonly valued standards and traditional attitude.” He also drew a connection between traditional “individualists” such as Zhuangzi, the poet Tao Yuanming (365-427 CE) and the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove (竹林七) as related to this modem trend of irreverence. -

Tianbo Li O Inglês Como Língua Global Na China English As a Global Language in China

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositório Institucional da Universidade de Aveiro Universidade de AveiroDepartamento de Línguas e Culturas 2005 Tianbo Li O Inglês como Língua Global na China English as a Global Language in China Universidade de AveiroDepartamento de Línguas e Culturas 2005 Tianbo Li O Inglês como Língua Global na China English as a Global Language in China dissertação apresentada à Universidade de Aveiro para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Estudos Ingleses, realizada sob a orientação científica do Dr. Gillian Moreira, Professor Auxiliar do Departamento de Línguas e Culturas da Universidade de Aveiro o júri presidente Prof.Doutor Anthony David Barker, Professor Associado da Universidade de Aveiro. Profa. Doutora Francesca Clare Rayner, Professora Auxiliar do Instituto de Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade do Minho. Profa.Doutora Gillian Grace Owen Moreira, Professora Auxiliar da Universidade de Aveiro. (Orientadora) agradecimentos My gratitude and esteem go to Professor Gillian Owen Grace Moreira, my supervisor in this work, without her patient direction and suggestions and corrections, this work would not have been presented here. Very special thanks to my family, who have been supporting and encouraging me. To Professor Susan Howcroft and Professor Teresa Roberto, who have constantly encouraged me to keep on my research. To the University of Aveiro, Portugal; Suihua Teachers College and No.7 Middle School of Suihua in Heilongjiang Province, P.R.China; China Mining Industry University; Nanjing University and No.50 Middle School of Nanjing in Jiangsu Province (PRC); which provided valid and valuable information for my dissertation. -

China Helped Block Fugitive's Cash

DESKEDT SCM,2001-07-19,1,SCM,3,SECOND EDITION COLOUR BLACK C5 ad1 27x5, The Peninsula (Page 3) - Thu Jul 19 01:01:24 2001 - Job7169776 SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST THURSDAY JULY 19 2001 HONG KONG 3 Top health China helped block fugitive’s cash inspector Documents show Beijing leaned on Turkish-controlled Cyprus to freeze account held by wife of ‘kingpin’ badly hurt Michael Chugani in Seattle Frozen assets in attack China exerted political pressure How Lai Changxing’s money ended up trapped in a northern Cyprus bank Clifford Lo to make a bank in Turkish-con- trolled Cyprus freeze a US$1 mil- US$2million US$1.6 million US$1million lion (HK$7.8 million) account A chief health inspector who led held by the wife of alleged smug- frontline campaigns to shut down gling kingpin Lai Changxing, doc- illegal slaughterhouses was criti- Sale of property Banque Nationale HSBC, Renfrew Security uments obtained by the South cally ill last night after being blud- development in China de Paris, Singapore Vancouver Bank and Trust China Morning Post suggest. geoned by three men. The documents show the off- October 19, 1999: Renfrew Security Bank to Lai’s wife, Tsang Mingna Wong Wai-wan, 46, underwent shore Renfrew Security Bank and brain surgery in Tuen Mun Hos- Trust froze the account on the pital after the attack, which hap- grounds that it may contain laun- pened as he made his way to his dered money from Hong Kong. Yuen Long office. Other documents show the Detectives were investigating funds were transferred to the whether the attack on the Food bank in the Turkish-controlled and Environmental Hygiene De- part of Cyprus from a Vancouver partment official was linked to his HSBC branch. -

An Assessment of Stephen Harper's China Policy

CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE / COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 36 / PCEMI 36 Master of Defence Studies Even Dief’ Sold Wheat: An Assessment of Stephen Harper’s China Policy By/par Lieutenant-Commander Todd Bonnar This paper was written by a student attending La présente étude a été rédigée par un stagiaire the Canadian Forces College in fulfilment of one du Collège des Forces canadiennes pour of the requirements of the Course of Studies. satisfaire à l'une des exigences du cours. L'étude The paper is a scholastic document, and thus est un document qui se rapporte au cours et contains facts and opinions, which the author contient donc des faits et des opinions que seul alone considered appropriate and correct for l'auteur considère appropriés et convenables au the subject. It does not necessarily reflect the sujet. Elle ne reflète pas nécessairement la policy or the opinion of any agency, including politique ou l'opinion d'un organisme the Government of Canada and the Canadian quelconque, y compris le gouvernement du Department of National Defence. This paper Canada et le ministère de la Défense nationale may not be released, quoted or copied, except du Canada. Il est défendu de diffuser, de citer ou with the express permission of the Canadian de reproduire cette étude sans la permission Department of National Defence. expresse du ministère de la Défense nationale. Word Count: 18,208 Compte de mots : 18, 208 i ABSTRACT The weak legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) owing to 25 years of market reform and the opening of the country to the world economy has radically transformed the Chinese society. -

PIERS 2016 Shanghai

PIERS 2016 Shanghai Progress In Electromagnetics Research Symposium Program August 8–11, 2016 Shanghai, CHINA www.emacademy.org www.piers.org For more information on PIERS, please visit us online at www.emacademy.org or www.piers.org. PIERS 2016 Shanghai Program CONTENTS TECHNICALPROGRAMSUMMARY . ......... 4 THEELECTROMAGNETICSACADEMY. ........... 11 JOURNAL: PROGRESS IN ELECTROMAGNETICS RESEARCH . ......... 11 PIERS2016SHANGHAIORGANIZATION . ........... 12 PIERS 2016 SHANGHAI SESSION ORGANIZERS . ......... 15 SYMPOSIUMVENUE ........................................ ........ 16 REGISTRATION ......................................... .......... 16 SPECIALEVENTS ....................................... ........... 16 PIERSONLINE ......................................... ........... 16 GUIDELINEFORPRESENTERS............................... ........... 17 PIERS 2016 SHANGHAI ORGANIZERS AND SPONSORS . ........ 18 PIERS2016SHANGHAIEXHIBITORS. ............. 18 MAPOFCONFERENCESITE ................................... ........ 19 GENERALINFORMATION ................................... .......... 22 PIERS 2016 SHANGHAI TECHNICAL PROGRAM . ............ 24 PIERS 2016 SHANGHAI SESSION OVERVIEW . ..........175 3 Progress In Electromagnetics Research Symposium TECHNICAL PROGRAM SUMMARY Monday AM, August 8, 2016 1A1 FocusSession.SC2: Transformation Optics 1 .................................................................. 24 1A2 FocusSession.SC2: Plasmonic Nanolasers and Active Metamaterials ....................................... 24 1A3 SC2: Thermal and Acoustic