Is Xi Jinping the Reformist Leader China Needs?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Data Supplement

China Data Supplement October 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 29 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 36 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 45 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR................................................................................................................ 54 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR....................................................................................................................... 61 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 66 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 October 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Nationalizing Transnational Mobility in Asia Xiang Biao, Brenda S

RETURN RETURN Nationalizing Transnational Mobility in Asia Xiang Biao, Brenda S. A. Yeoh, and Mika Toyota, eds. Duke University Press Durham and London 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-f ree paper ♾ Cover by Heather Hensley. Interior by Courtney Leigh Baker. Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Return : nationalizing transnational mobility in Asia / Xiang Biao, Brenda S. A. Yeoh, and Mika Toyota, editors. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5516-8 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5531-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Return migration—Asia. 2. Asia—Emigration and immigration. I. Xiang, Biao. II. Yeoh, Brenda S. A. III. Toyota, Mika. jv8490.r48 2013 325.5—dc23 2013018964 CONTENTS Acknowledgments ➤➤ vii Introduction Return and the Reordering of Transnational Mobility in Asia ➤➤ 1 Xiang biao Chapter One To Return or Not to Return ➤➤ 21 The Changing Meaning of Mobility among Japanese Brazilians, 1908–2010 Koji sasaKi Chapter Two Soldier’s Home ➤➤ 39 War, Migration, and Delayed Return in Postwar Japan MariKo asano TaManoi Chapter Three Guiqiao as Political Subjects in the Making of the People’s Republic of China, 1949–1979 ➤➤ 63 Wang Cangbai Chapter Four Transnational Encapsulation ➤➤ 83 Compulsory Return as a Labor-M igration Control in East Asia Xiang biao Chapter Five Cambodians Go “Home” ➤➤ 100 Forced Returns and Redisplacement Thirty Years after the American War in Indochina -

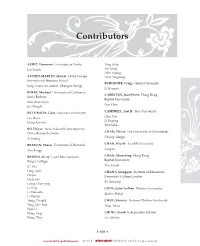

Contributors.Indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM F-479 /203/BER00069/Work/Indd/%20Backmatter

02_Contributors.indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM f-479 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter Contributors AUBIÉ, Hermann University of Turku Yang Jiang Liu Xiaobo Yao Ming Zhao Ziyang AUSTIN-MARTIN, Marcel China Europe Zhou Youguang International Business School BURGDOFF, Craig Capital University Jiang Zemin (co-author: Zhengxu Wang) Li Hongzhi BERRY, Michael University of California, CABESTAN, Jean-Pierre Hong Kong Santa Barbara Baptist University Hou Hsiao-hsien Lien Chan Jia Zhangke CAMPBELL, Joel R. Troy University BETTINSON, Gary Lancaster University Chen Yun Lee, Bruce Li Keqiang Wong Kar-wai Wen Jiabao BO Zhiyue New Zealand Contemporary CHAN, Felicia The University of Manchester China Research Centre Cheung, Maggie Xi Jinping BRESLIN, Shaun University of Warwick CHAN, Hiu M. Cardiff University Zhu Rongji Gong Li BROWN, Kerry Lau China Institute, CHAN, Shun-hing Hong Kong King’s College Baptist University Bo Yibo Zen, Joseph Fang Lizhi CHANG Xiangqun Institute of Education, Hu Jia University College London Hu Jintao Fei Xiaotong Leung Chun-ying Li Peng CHEN, Julie Yu-Wen Palacky University Li Xiannian Kadeer, Rebiya Li Xiaolin Tsang, Donald CHEN, Szu-wei National Taiwan University Tung Chee-hwa Teng, Teresa Wan Li Wang Yang CHING, Frank Independent Scholar Wang Zhen Lee, Martin • 569 • www.berkshirepublishing.com © 2015 Berkshire Publishing grouP, all rights reserved. 02_Contributors.indd Page 570 9/22/15 12:09 PM f-500 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter • Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography • Volume 4 • COHEN, Jerome A. New -

Insights for Intra-Party Tensions?

Hong Kong as a proxy battlefield Insights for Intra-Party tensions? Zhang Xiaoming 张晓明, the director of the State Council Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office 国务 院港澳办, was replaced a few days ago, as vice-director of the small leading group of the same name, by the current Minister of Public Security, Zhao Kezhi 赵克志. That said, it seems Hong Kong’s issues run deeper than just a few personnel appointments. Is the special administrative zone becoming a proxy battleground for opposing political forces inside the Party? The timeline and people involved suggest that parts of the ongoing crisis might have been made by design by outgoing political networks amid the anti-corruption campaign. From the selection of Carrie Lam 林郑月娥, the underpinnings of the Hong Kong and Macau affairs system, to the bid for the London Stock Exchange, there is more than meets the eye. The “Manchurian” Candidate and the Jiangpai From the beginning, the opinion was that Madame Lam would be a short-live replacement for Liang Zhenying 梁振英. Carrie Lam, who actually joined the protest – even for a brief moment – for universal suffrage back in 2014, stayed close to the negotiation with Beijing, unlike some of her counterparts who were refused entry in Shenzhen back in 2015. She then became one of the favorite faces of the administration, especially in late 2016, when Liang Zhenying1 announced he would not be running for re-election. Liang, a representative of the “old regime” – associated with both Zeng Qinghong 曾庆红2 and Zhang Dejiang 张德江, was creating issues leading to the deterioration of the situation in Hong Kong (i.e. -

YAO-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf

CONSUMING SCIENCE: A HISTORY OF SOFT DRINKS IN MODERN CHINA A Dissertation Presented to The Academic Faculty by Liang Yao In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of History and Sociology Georgia Institute of Technology May 2016 COPYRIGHT © 2015 BY LIANG YAO CONSUMING SCIENCE: A HISTORY OF SOFT DRINKS IN MODERN CHINA Approved by: Dr. Hanchao Lu, Advisor Dr. Laura Bier School of History and Sociology School of History and Sociology Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. John Krige Dr. Kristin Stapleton chool of History and Sociology History Department Georgia Institute of Technology University at Buffalo Dr. Steven Usselman chool of History and Sociology Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: December 2, 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would never have finished my dissertation without the guidance, help, and support from my committee members, friends, and family. Firstly, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor Professor Hanchao Lu for his caring, continuous support, and excellent intellectual guidance in all the time of research and writing of this dissertation. During my graduate study at Georgia Tech, Professor Lu guided me where and how to find dissertation sources, taught me how to express ideas and write articles like a historian. He provided me opportunities to teach history courses on my own. He also encouraged me to participate in conferences and publish articles on journals in the field. His patience and endless support helped me overcome numerous difficulties and I could not have imagined having a better advisor and mentor for my doctorial study. -

Paper by Professor ZHAO Bingzhi, Dean, College for Criminal Law

Paper by Professor ZHAO Bingzhi, Dean, College for Criminal Law Science and School of Law, Beijing Normal University and President, Criminal Law Research Committee, China Law Society, Mainland China Criminal Legality in Mainland China’s 30 Years of Reform and Opening-up — Perspective from a Number of Typical Cases (Translation of original speech in Chinese) Table of Contents Preamble I. Outline of the criminal legality prior to the promulgation and implementation of the 1997 Penal Code (1978-1997) (I) Lin Biao & Jiang Qing Counter-revolutionary Group Case (II) Han Kun Bribe-taking Case (III) Jiang Aizhen Intentional Homicide Case (IV) December Eighth Karamai City (Xinjiang) Major Liability Incident & Negligence of Duty Case II. Outline of the criminal legality subsequent to the promulgation and implementation of the 1997 Penal Code (1997-2008) (I) Zhang Ziqiang Case (II) Gong Jianping Football “Black Whistle” Case (III) Zheng Xiaoyu Bribe-taking & Negligence of Duty Case (IV) Xu Ting Theft Case (V) Several Typical Cases with Criminal Fled Away (Yu Zhendong Case, Hu Xing Case and Lai Changxing Case) Conclusion Preamble The reform and opening-up cause of China has witnessed a 30-year splendid and brilliant course since the third plenary session of the 11th Central Committee in December 1978. The 30 years of reform and opening-up was accompanied with the 30 years of hardships and explorations, the 30 years of fluctuations and transitions and the 30 years of advancements within each passing day. We have, during these 30 years of reform and opening-up, gone through earthshaking social developments and changes and have acquired spectacular achievements to which worldwide attention was drawn. -

The Prevention and Control of Economic Crime in China

The Prevention and Control of Economic Crime in China: A Critical Analysis of the Law and its Administration Enze Liu Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Advanced Legal Studies School of Advanced Study, University of London September 2017 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis represents my own work. Where information has been used they have been duly acknowledged. Signature: …………………………. Date: ………………………………. 2 Abstract Economic crime and corruption has been an issue throughout Chinese history. While there may be scope for discussion as to the significance of public confidence in the integrity of a government, in practical terms the government of China has had to focus attention on maintaining confidence in its integrity as an issue for stability. Since the establishment of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its assumption of power and in particular after the ‘Opening’ of the Chinese economy, abusive conduct on the part of those in positions of privilege, primarily in governmental organisations, has arguably reached an unprecedented level. In turn, this is impeding development as far as it undermines public confidence, accelerates jealousy and forges an even wider gap between rich and poor, thereby threatening the stability and security of civil societies. More importantly, these abuses undermine the reputation of the CCP and the government. China naturally consider this as of key significance in attracting foreign investment and assuming its leading role in the world economy. While there have been many attempts to curb economic crime, the traditional capabilities of the law and particularly the criminal justice system have in general terms been found to be inadequate. -

The CCP Central Committee's Leading Small Groups Alice Miller

Miller, China Leadership Monitor, No. 26 The CCP Central Committee’s Leading Small Groups Alice Miller For several decades, the Chinese leadership has used informal bodies called “leading small groups” to advise the Party Politburo on policy and to coordinate implementation of policy decisions made by the Politburo and supervised by the Secretariat. Because these groups deal with sensitive leadership processes, PRC media refer to them very rarely, and almost never publicize lists of their members on a current basis. Even the limited accessible view of these groups and their evolution, however, offers insight into the structure of power and working relationships of the top Party leadership under Hu Jintao. A listing of the Central Committee “leading groups” (lingdao xiaozu 领导小组), or just “small groups” (xiaozu 小组), that are directly subordinate to the Party Secretariat and report to the Politburo and its Standing Committee and their members is appended to this article. First created in 1958, these groups are never incorporated into publicly available charts or explanations of Party institutions on a current basis. PRC media occasionally refer to them in the course of reporting on leadership policy processes, and they sometimes mention a leader’s membership in one of them. The only instance in the entire post-Mao era in which PRC media listed the current members of any of these groups was on 2003, when the PRC-controlled Hong Kong newspaper Wen Wei Po publicized a membership list of the Central Committee Taiwan Work Leading Small Group. (Wen Wei Po, 26 December 2003) This has meant that even basic insight into these groups’ current roles and their membership requires painstaking compilation of the occasional references to them in PRC media. -

Please Click Here to See the List of 315

The Tiananmen Papers Revisited Alfred L. Chan, Andrew J. Nathan Journal: The China Quarterly / Volume 177 / 2004 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741004000116 Published online: 11 May 2004, pp. 190-214 The Tiananmen Papers: An Editor's Reflections Andrew J. Nathan Journal: The China Quarterly / Volume 167 / 2001 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0009443901000407 Published online: 01 September 2001, pp. 724-737 China's Universities since Tiananmen: A Critical Assessment Ruth Hayhoe Journal: The China Quarterly / Volume 134 / 1993 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741000029696 Published online: 01 February 2009, pp. 291-309 Beijing and Taipei: Dialectics in Post-Tiananmen Interactions Chong-Pin Lin Journal: The China Quarterly / Volume 136 / 1993 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741000032331 Published online: 01 February 2009, pp. 770-804 The “Shekou Storm”: Changes in the Mentality of Chinese Youth Prior to Tiananmen Luo Xu Journal: The China Quarterly / Volume 142 / 1995 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741000035050 Published online: 01 February 2009, pp. 541-572 The Road to Tiananmen Square. By HoreCharlie. [London: Bookmarks, 1991. 159 pp. £4.95.] Nicola Macbean Journal: The China Quarterly / Volume 130 / 1992 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741000040832 Published online: 01 February 2009, pp. 417-419 China Rising: The Meaning of Tiananmen. By FeigonLee. [Chicago: DeeIvan R., 1990. 269 pp. $19.95.] Gregor Benton Journal: The China Quarterly / Volume 125 / 1991 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741000030459 Published online: 01 February 2009, pp. 168-169 PLA and the Tiananmen Crisis. Edited by YangRichard H.. [Kaohsiung, Taiwan: SCPS Papers No. 1, 101989. -

The Making of China's Peace with Japan

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY SOURCES IN CHINESE Books Jin, Chongji. ed. (principal editor). Zhou Enlai zhuan 1898–1949 (Biography of Zhou Enlai 1898–1949). Edited by Zhonggong-zhongyang wenxian-yanjiushi. Beijing: Renmin-chubanshe and Zhongyang wenxian-chubanshe, 1989. Jin, Chongji. ed. (principal editor). Zhou Enlai zhuan (Biography of Zhou Enlai). 2 vols. Edited by Zhonggong-zhongyang wenxian-yanjiushi. Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian-chubanshe, 1998. Jinian Zhou Enlai chuban-faxing weiyuanhui. ed. Ribenren xinmuzhong de Zhou Enlai (Zhou Enlai in the Hearts of the Japanese). Trans by Liu Shouxu. Beijing: Zhonggong-zhongyang dangxiao-chubanshe, 1991. Li, Enmin. Zhongri minjian jingji waijiao (Sino-Japanese Private Economic Diplomacy). Beijing: Renmin-chubanshe, 1997. Li, Rongde. Liao Chengzhi. Singapore: Yongsheng-shuju, 1992. Liao Chengzhi ziliaoji (Documents on Liao Chengzhi). Hong Kong: Taozhai- shuwu, 1973. Liu, Wusheng. Zhou Enlai de wannian suiyue (Late Years of Zhou Enlai). Hong Kong: Sanlian-shudian, 2006. Sun, Pinghua. Wode lulishu (My Autobiography). Beijing: Shijie-zhishi chu- banshe, 1998. Wang, Junyan. Da-waijiaojia Zhou Enlai (Zhou Enlai: A Great Diplomat). Beijing: Jingji-ribao chubanshe, 1998. Wang, Xuanren. Nibuzhidao de Zhou Enlai (Zhou Enlai That You Do Not Know). Taipei: Wanyuan-tushu, 2005. © The Author(s) 2017 271 M. Itoh, The Making of China’s Peace with Japan, DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-4008-5 272 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Wang, Yongxiang and Takahashi, Tsuyoshi. eds. Riben liuxue-shiqi de Zhou Enlai (Zhou Enlai During his Study Period in Japan). Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian- chubanshe, 2001. Wu, Xuewen. Fengyu yinqing: Wosuo jingli de Zhongri guanxi (Wind, Rain, Cloud, Sun: My Autobiography and Sino-Japanese Relations). Beijing: Shijie-zhishi chubanshe, 2002. -

1 Annotated Bibliography of Liu Xiaobo's Texts in Chronological Order

1 Annotated Bibliography of Liu Xiaobo’s Texts in Chronological Order Year Chinese Title English Title Category 04/1984 艺术直觉 On Artistic Intuition 关系学院 学 1 1984 庄子 On Zhuangzi 社科学战线 05/1985 和冲突 – 中西美意的差别 Harmony and Conflicts – Differences between Chinese 京师范大学 and Western Aesthetics 学 07/1985 味觉说 Theory of Taste 科知 Early 1986 种的美思潮 – 徐星陈村索拉的 A New Aesthetic Trend – Remarks Inspired by the Works 文学 2 部作谈起 of Xu Xing, Chen Cun and Liu Suola (1986:3) 04/1986 无法回避的思 – 几部关知子的小说 Unavoidable Reflection – Contemplating Stories on 中 / MA 谈起 Intellectuals (EN 94) Thesis 03/10/1986 机,时期文学面临机 Crisis! New Era’s Literature is Facing a Crisis (FR) 深圳青 10/1986 李厚对 – Dialogue with Li Zehou (1) 中 1986 On Solitude (EN) 家 1988:2 1 th Zhuangzi was a Chinese Daoist thinker who lived around the 4 century BC during the Warring States period, when the Hundred Schools of Thought flourished. 2 Shanghai writer Chen Cun (1954-) and Beijing writers Liu Suola (1955-) and Xu Xing (1956-) who expressed contempt for the formal education of the mid-1980s and its pretention. Liu Xiaobo responded to a conservative attack on 'superfluous people' by defending these three writers who were popular in 1985 and who would be also attacked in 1990 as “rebellious aristocrats” whose works displayed a “liumang mentality.” He wrote a positive interpretation of their way of “ridiculing the sacred, the lofty and commonly valued standards and traditional attitude.” He also drew a connection between traditional “individualists” such as Zhuangzi, the poet Tao Yuanming (365-427 CE) and the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove (竹林七) as related to this modem trend of irreverence.