Reinforcing Leninist Means of Corruption Control in China: Centralization, Regulatory Changes and Party-State Integration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 1: Rank of China's 338 Prefecture-Level Cities

Appendix 1: Rank of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities © The Author(s) 2018 149 Y. Zheng, K. Deng, State Failure and Distorted Urbanisation in Post-Mao’s China, 1993–2012, Palgrave Studies in Economic History, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92168-6 150 First-tier cities (4) Beijing Shanghai Guangzhou Shenzhen First-tier cities-to-be (15) Chengdu Hangzhou Wuhan Nanjing Chongqing Tianjin Suzhou苏州 Appendix Rank 1: of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities Xi’an Changsha Shenyang Qingdao Zhengzhou Dalian Dongguan Ningbo Second-tier cities (30) Xiamen Fuzhou福州 Wuxi Hefei Kunming Harbin Jinan Foshan Changchun Wenzhou Shijiazhuang Nanning Changzhou Quanzhou Nanchang Guiyang Taiyuan Jinhua Zhuhai Huizhou Xuzhou Yantai Jiaxing Nantong Urumqi Shaoxing Zhongshan Taizhou Lanzhou Haikou Third-tier cities (70) Weifang Baoding Zhenjiang Yangzhou Guilin Tangshan Sanya Huhehot Langfang Luoyang Weihai Yangcheng Linyi Jiangmen Taizhou Zhangzhou Handan Jining Wuhu Zibo Yinchuan Liuzhou Mianyang Zhanjiang Anshan Huzhou Shantou Nanping Ganzhou Daqing Yichang Baotou Xianyang Qinhuangdao Lianyungang Zhuzhou Putian Jilin Huai’an Zhaoqing Ningde Hengyang Dandong Lijiang Jieyang Sanming Zhoushan Xiaogan Qiqihar Jiujiang Longyan Cangzhou Fushun Xiangyang Shangrao Yingkou Bengbu Lishui Yueyang Qingyuan Jingzhou Taian Quzhou Panjin Dongying Nanyang Ma’anshan Nanchong Xining Yanbian prefecture Fourth-tier cities (90) Leshan Xiangtan Zunyi Suqian Xinxiang Xinyang Chuzhou Jinzhou Chaozhou Huanggang Kaifeng Deyang Dezhou Meizhou Ordos Xingtai Maoming Jingdezhen Shaoguan -

002170196E1c16a28b910f.Pdf

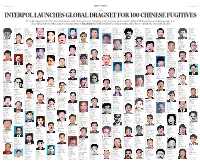

6 THURSDAY, APRIL 23, 2015 DOCUMENT CHINA DAILY 7 JUSTICE INTERPOL LAUNCHES GLOBAL DRAGNET FOR 100 CHINESE FUGITIVES It’s called Operation Sky Net. Amid the nation’s intensifying antigraft campaign, arrest warrants were issued by Interpol China for former State employees and others suspected of a wide range of corrupt practices. China Daily was authorized by the Chinese justice authorities to publish the information below. Language spoken: Liu Xu Charges: Place of birth: Anhui property and goods Language spoken: Zeng Ziheng He Jian Qiu Gengmin Wang Qingwei Wang Linjuan Chinese, English Sex: Male Embezzlement Language spoken: of another party by Chinese Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Female Charges: Date of birth: Chinese, English fraud Charges: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Accepting bribes 07/02/1984 Charges: Embezzlement Embezzlement 15/07/1971 14/11/1965 15/05/1962 03/01/1972 17/07/1980 Place of birth: Beijing Place of birth: Henan Language spoken: Place of birth: Place of birth: Place of birth: Language spoken: Language spoken: Chinese Zhejiang Jinan, Shandong Jilin Chinese, English Chinese Charges: Graft Language spoken: Language spoken: Language spoken: Charges: Corruption Charges: Chinese Chinese, English Chinese Embezzlement Charges: Contract Charges: Commits Charges: fraud, and flight of fraud by means of a Misappropriation of Yang Xiuzhu 25/11/1945 Place of birth: Chinese Zhang Liping capital contribution Chu Shilin letter of credit Dai Xuemin public funds Sex: Female -

Christian Women and the Making of a Modern Chinese Family: an Exploration of Nü Duo 女鐸, 1912–1951

Christian Women and the Making of a Modern Chinese Family: an Exploration of Nü duo 女鐸, 1912–1951 Zhou Yun A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University February 2019 © Copyright by Zhou Yun 2019 All Rights Reserved Except where otherwise acknowledged, this thesis is my own original work. Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Benjamin Penny for his valuable suggestions and constant patience throughout my five years at The Australian National University (ANU). His invitation to study for a Doctorate at Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW) not only made this project possible but also kindled my academic pursuit of the history of Christianity. Coming from a research background of contemporary Christian movements among diaspora Chinese, I realise that an appreciation of the present cannot be fully achieved without a thorough study of the past. I was very grateful to be given the opportunity to research the Republican era and in particular the development of Christianity among Chinese women. I wish to thank my two co-advisers—Dr. Wei Shuge and Dr. Zhu Yujie—for their time and guidance. Shuge’s advice has been especially helpful in the development of my thesis. Her honest critiques and insightful suggestions demonstrated how to conduct conscientious scholarship. I would also like to extend my thanks to friends and colleagues who helped me with my research in various ways. Special thanks to Dr. Caroline Stevenson for her great proof reading skills and Dr. Paul Farrelly for his time in checking the revised parts of my thesis. -

As of April 7, 2014 Select List of Delegates Boao Forum for Asia

As of April 7, 2014 Select List of Delegates Boao Forum for Asia Annual Conference 2014 State/Government Leaders 1. H.E. LI Keqiang, Premier, State Council, the People’s Republic of China 2. The Hon. Tony Abbott, Prime Minister, the Common-wealth of Australia 3. H.E. Chung Hongwon, Prime Minister, Republic of Korea 4. H.E. Thongsing Thammavong, Prime Minister, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic 5. Rt. Hon. Dr. Hage Geingob, Prime Minister, the Republic of Namibia 6. H.E. Nawaz Sharif, Prime Minister, Islamic Republic of Pakistan 7. H.E. Kay Rala Xanana Gusmao, Prime Minister, the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste 8. H.E. Arkady Vladimirovich Dvorkovich, Deputy Prime Minister, Russian Federation 9. H.E. Vu Duc Dam, Vice Prime Minister, Socialist Republic of Vietnam 10. H. E. YANG Jiechi, State Councilor, People’s Republic of China 11. FUKUDA Yasuo, Former Prime Minister, Japan 12. ZENG Peiyan, Former Vice Premier, China 13. Abdullah bin Haji Ahmad BADAWI, Former Prime Minister, Malaysia 14. GOH Chok Tong, Emeritus Senior Minister, Republic of Singapore 15. Jean-Pierre RAFFARIN, Former Prime Minister, France 16. Dominique de VILLEPIN, former Prime Minister, France 17. Fidel V. RAMOS, Former President, the Philippines 18. Bob HAWKE, Former Prime Minister of Australia 19. HAN Duck-Soo, Chairman, KITA; Former Prime Minister, Republic of Korea 20. ZHOU Xiaochuan, Governor, People’s Bank of China 21. Surakiart SATHIRATHAI, Chairman of the Asian Peace and Reconciliation Council (APRC), Former Deputy Prime Minister & Minister of Foreign Affairs of Thailand 22. Peter COSTELLO, Former Treasurer, Commonwealth of Australia; Chairman, Australian Government Sovereign Wealth Fund, Future Fund; Managing Director, BKK Partners; Chairman, ECG Advisory Solutions 23. -

China Special Edition About Asia Society Australia

2019 China Special Edition About Asia Society Australia For over 60 years globally, and over two Our mission is to prepare Australian leaders and the community for deeper and sustained engagement decades in Australia, Asia Society has with Asia. been building bridges of understanding Asia Society Australia is a centre of Asia Society – between leaders and change-makers of a preeminent global non-profit organisation Asia, Australia, and the United States. dedicated to Asia, founded in 1956 by John D. Rockefeller 3rd, with centres in New York, Hong Launched in 1997 by then Prime Minister John Kong, Houston, Los Angeles, Manila, Melbourne, Howard, Asia Society Australia is the leading national Mumbai, San Francisco, Seoul, Shanghai, Sydney, centre for engagement with Asia, with a centre Tokyo, Washington DC and Zurich. in Melbourne and an office in Sydney. We are a Across the fields of arts, business, culture, education not-for-profit, non-governmental and non-political and policy, Asia Society provides insight, generates organisation empowered by leading Australian ideas, and promotes collaboration to address and regional business, government, education and present challenges and create a shared future. cultural institutions. asiasociety.org/Australia This series was made possible through the “Desai-Oxnam Innovation Fund” established by the Asia Society to celebrate generosity and almost 40 years of combined service of former Asia Society Presidents Dr. Vishakha Desai and Dr Robert Oxnam. The 2019 edition is supported by the Victorian Government. 2019 China Special Edition About Disruptive Asia Disruptive Asia is a thought-leadership The Asia debate has long ceased to be the exclusive intellectual domain of the foreign policy project by Asia Society Australia, and business elite. -

P020110307527551165137.Pdf

CONTENT 1.MESSAGE FROM DIRECTOR …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 03 2.ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 05 3.HIGHLIGHTS OF ACHIEVEMENTS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 Coexistence of Conserve and Research----“The Germplasm Bank of Wild Species ” services biodiversity protection and socio-economic development ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 The Structure, Activity and New Drug Pre-Clinical Research of Monoterpene Indole Alkaloids ………………………………………… 09 Anti-Cancer Constituents in the Herb Medicine-Shengma (Cimicifuga L) ……………………………………………………………………………… 10 Floristic Study on the Seed Plants of Yaoshan Mountain in Northeast Yunnan …………………………………………………………………… 11 Higher Fungi Resources and Chemical Composition in Alpine and Sub-alpine Regions in Southwest China ……………………… 12 Research Progress on Natural Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV) Inhibitors…………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Predicting Global Change through Reconstruction Research of Paleoclimate………………………………………………………………………… 14 Chemical Composition of a traditional Chinese medicine-Swertia mileensis……………………………………………………………………………… 15 Mountain Ecosystem Research has Made New Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Plant Cyclic Peptide has Made Important Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Progresses in Computational Chemistry Research ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 New Progress in the Total Synthesis of Natural Products ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… -

Article on the Un Convention Against Transnational

ARTICLE ON THE UN CONVENTION AGAINST TRANSNATIONAL ORGANIZED CRIME AND CONVENTION AGAINST CORRUPTION IN CHINA: DOMESTIC EFFORTS AND INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION Shang Haowen Huang Gui Table of Contents I.INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 85 II.THE UNTOC AND THE UNCAC IN CHINA: FROM ACCEPTANCE TO IMPLEMENTATION ................................................................................. 90 A. Challenges in Bolstering Anticorruption Cooperation ................. 90 B. Overriding Principles of Combating Corruption .......................... 95 1. Good Governance ................................................................... 95 2. Rule of Law ........................................................................... 102 III.DOMESTIC ANTI-CORRUPTION LEGAL FRAMEWORK .............................. 106 A. Overview of Updates in Chinese Anticorruption Legal Framework ..................................................................................................... 107 B. To Promise and Propose Giving a Bribe Was First Stipulated in the Criminal Law ........................................................................ 109 C. The Corruption Involving Foreign and International Officials Could Be Cracked down on by Criminal Law ........................... 111 D. The Corruption Involving Legal Person and its Liabilities ........ 112 IV.INTERNATIONAL ANTICORRUPTION COOPERATION PRACTICE ............... 115 A. The Domestic Legal Basis of International Anticorruption -

CHINA DAILY for Chinese and Global Markets

OLD MOBILES CHANCE RELATIONS LOTUS FROM SPACE Outlining the high stakes Flower seeds made Showroom opening to attract > p13 in future China-US ties a tour beyond Earth buyers of hand-assembled cars > ACROSS AMERICA, PAGE 2 > CHINA, PAGE 7 WEDNESDAY, June 19, 2013 chinadailyusa.com $1 The ‘Long March’ to Tinseltown By LIU WEI in shanghai “It is a long way to go,” he [email protected] says, “but I believe as the Chi- nese = lm market keeps growing The next Kung Fu Panda so fast, it is totally possible that will be the brainchild of both Chinese capital will hold shares American and Chinese film- in the major six Hollywood stu- makers and production will dios. It is just a matter of time.” start in August, says Peter Li, China’s Wanda Cultural managing director of China Group is one of the pioneers Media Capital, co-investor of in this process. In 2012 Wanda Oriental DreamWorks, a joint acquired AMC, the second venture with DreamWorks largest theater chain in North Animation. America, for $2.6 billion. CMC co-founded Oriental What Ye Ning, the group’s DreamWorks in 2012 with vice-president, has learned DreamWorks, Shanghai Media from the following integration Group and Shanghai Alliance is, = rst of all, trust and respect. Investment, with the aim of “The managing team of CHARACTER BUILDING producing and distributing ani- AMC was worried that we mated and live-action content would send a group of yellow PHOTO BY SUN CHENBEI / CHINA DAILY for Chinese and global markets. faces to replace them,” Ye says, From le : Li Xiaolin, president -

Xi Jinping's 'New Era' – Continuities and Change

No. 88 February 2020 Xi Jinping’s ‘New Era’ – Continuities and Change Anurag Viswanath Singapore based China Analyst and Adjunct Fellow, Institute of Chinese [email protected] supplemented with the addition of ‗Xi Jinping Thought‘ and ‗New Era‘ at the beginning and In post-1978 China, moderniser par excellence at the end. China‘s transformation is evident in Deng Xiaoping‘s ‗reform and open door‘ Xi‘s 2020 New Year Speech, with China‘s per (gaige and kaifang) defined China‘s political capita GDP reaching $10,000 in 2019. In 1978, and economic terrain. In 2020, forty odd years when China was on the cusp of reforms, it was after Deng‘s reforms, observers wonder if ‗the $156. Indeed, the Chinese themselves say reform era, launched by Deng Xiaoping in ‗Under Mao, the Chinese people stood up 1978, is over‘ (Minxin Pei: 2018). China has (zhan qilai); under Deng, the Chinese people changed, with far-reaching changes under got rich (fu qilai); and under Xi, the Chinese President Xi Jinping. Xi has gifted China with people are getting stronger (qiang qilai)‘ a new guiding ideology ‗Xi Jinping: Thought (Susan Shirk, 2018:27)2. on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for the New Era‘ codified in the constitution by the Xi‘s rise in 2012 coincided with China sealing th Second Plenum of the 19 Party Congress in its place as the world‘s second largest economy January 2018. Xi has introduced no less than (in 2010). The decade had seen much 300 reforms that have signalled changes and optimism about China‘s aggregate economy departures in ‗every aspect of the party, surpassing that of America in 2025 (Muhlhahn, 1 government, economy, military and society‘ 2019:167)3. -

Combatting Corruption in the “Era of Xi Jinping”: a Law and Economics Perspective

Hastings International and Comparative Law Review Volume 43 Number 2 Summer 2020 Article 3 Summer 2020 Combatting Corruption in the “Era of Xi Jinping”: A Law and Economics Perspective Miron Mushkat Roda Mushkat Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_international_comparative_law_review Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Miron Mushkat and Roda Mushkat, Combatting Corruption in the “Era of Xi Jinping”: A Law and Economics Perspective, 43 HASTINGS INT'L & COMP. L. Rev. 137 (2020). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_international_comparative_law_review/vol43/ iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 - Mushkat_HICLR_V43-2 (Do Not Delette) 5/1/2020 4:08 PM Combatting Corruption in the “Era of Xi Jinping”: A Law and Economics Perspective MIRON MUSHKAT AND RODA MUSHKAT Abstract Pervasive graft, widely observed throughout Chinese history but deprived of proper outlets and suppressed in the years following the Communist Revolution, resurfaced on massive scale when partial marketization of the economy was embraced in 1978 and beyond. The authorities had endeavored to alleviate the problem, but in an uneven and less than determined fashion. The battle against corruption has greatly intensified after Xi Jinping ascended to power in 2012. The multiyear antigraft campaign that has unfolded has been carried out in an ironfisted and relentless fashion. -

Narrative Vitae Of

CV of G. Chen Narrative Vitae of GANG CHEN ______________________________________________________________________________ Carl Richard Soderberg Professor E-mail: [email protected] Mechanical Engineering Department http://web.mit.edu/nanoengineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology Tel: (617) 253-0006 (Office) 77 Massachusetts Avenue, 3-260 (617) 253-7413 (Assistant) Cambridge, MA 02139 Fax: (617) 324- 5519 ____________________________________________________________________________________ Gang Chen is currently Carl Richard Soderberg Professor of Power Engineering and Head of the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He received his bachelor and master degrees from the Power Engineering Department, Huazhong Institute of Technology (now Huazhong University of Science and Technology or HUST in short), China, in 1984 and 1987, respectively. He stayed at HUST as a lecturer from 1987-1989. He received his PhD degree from the Mechanical Engineering Department, UC Berkeley, in 1993, studying under then Chancellor Chang-Lin Tien. He was an assistant professor at Duke University from 1993 to 1997, a tenured associate professor at University of California at Los Angeles from 1997 to 2001. He joined MIT in 2001 as a tenured associate professor, and was promoted to full professor in 2004. Professor Chen’s research interests center on nanoscale thermal transport and energy conversion phenomena, and their applications in energy storage and conversion, thermal management, and water treatment and desalination. He has made important contributions to the understanding of heat conduction in nanostructures structures such as ballistic and coherent heat conduction in quantum wells and superlattices via both modeling and experimental studies. He and his collaborators invented ways to extract phonon mean free path distributions in solids by exploiting ballistic phonon transport processes and advanced first principles simulation tools to compute phonon thermal conductivity. -

China Story Yearbook 2014: Shared Destiny

SHARED DESTINY 共同命运 EDITED BY Geremie R Barmé WITH Linda Jaivin AND Jeremy Goldkorn C HINA S TORY YEARBOOK 2 0 14 © The Australian National Univeristy (as represented by the Australian Centre on China in the World) First published October 2015 by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Shared destiny / Geremie R Barmé, Linda Jaivin, Jeremy Goldkorn, editors. ISBN: 9781925022933 (paperback) 9781925022940 (ebook) Series: China story yearbook ; 2014. Subjects: China--Politics and government--2002- | China--Foreign relations--2002- China--Relations--Asia | Asia--Relations--China | China--Relations--Pacific Area Pacific Area--Relations--China. Other Creators/Contributors: Barmé, Geremie, editor. Jaivin, Linda, editor. | Goldkorn, Jeremy, editor. Dewey Number: 915.1156 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. This publication is made available as an Open Educational Resource through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike 3.0 Australia Licence: http://creativecommons.org/licensese/by-nc-sa/3.0/au/deed.en Note on Visual Material All images in this publication have been fully accredited. As this is a non-commercial publication, certain images have been used under a Creative Commons licence. These images have been sourced from flickr, Wikipedia Commons and the copyright owner of each original picture is acknowledged and indicated in the source information.