European Parliament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Parliament

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT ITRE(2005)0316_1 COMMITTEE ON INDUSTRY, RESEARCH AND ENERGY Meeting Wednesday, 16 March 2005 from 15:00 to 18:30, Brussels Thursday, 17 March 2005 from 9:00 to 12:30, Brussels PUBLISHED DRAFT AGENDA Wednesday, 16 March 2005, from 15:00 to 18:30 1. Adoption of draft agenda 2. Announcements from the Chair 3. Approval of minutes of meeting of: Minutes of 14/12/04 PE353.264 v01-00 Minutes of 11/01/05 PE353.386 v01-00 Minutes of 17/01/05 PE353.441 v01-00 * * * In the presence of the Council and the European Commission At 03.00pm : VOTE 4. European Security Strategy ITRE/6/24333 PA - PE353.510v02-00 AM - PE353.739v01-00 Draftperson: Jan Christian Ehler (EPP-ED) - Adoption of a draft opinion - Deadline for tabling amendments: 15.02.2005 12:00 2004/2167(INI) Main: AFET F - Helmut Kuhne (PSE) PE349.862 v01-00 PE353.585 v01-00 * * * ITRE_OJ(2005)0316_1_v01-00_EN.rtf - 1 - ITRE_OJ(2005)0316_1 v01-00 EN EN From 03.05pm to 04.00pm: 5. Visit of Mr. Jeannot KRECKÉ, Minister in-office of the Council, for Economics and External Trade ITRE/6/26494 - Exchange of views * * * 6. Strengthening European competitiveness: the impact of industrial change on the policy and role of SMEs ITRE/6/23588 PR - PE355.420v01-00 Rapporteur: Dominique Vlasto (EPP-ED) - Consideration of a draft report - Set deadline for tabling amendments 2004/2154(INI) COM(2004)0274 Main: ITRE F - Dominique Vlasto (EPP-ED) Opinion: ECON, EMPL Joint discussion: 7. (Chemicals: REACH system and European Chemicals Agency, amending Directive 1999/45/EC and regulation on pollutants ITRE/6/21103 PA - PE353.595v01-00 Draftperson: Lena Ek (ALDE) - Consideration of a draft opinion - Set deadline for tabling amendments ***I 2003/0256(COD) COM(2003)0644 - C5-0530/2003 Main: ENVI F* - Guido Sacconi (PSE) Opinion: INTA, BUDG, ECON, EMPL, ITRE, IMCO, JURI, FEMM 8. -

13. Transatlantycka Rada Gospodarcza (Debata)

C 168 E/6 Dziennik Urzędowy Unii Europejskiej PL 3.7.2008 Środa, 7 maja 2008 r. PRZEWODNICTWO: Rodi KRATSA-TSAGAROPOULOU Wiceprzewodnicząca Głos zabrali: Wolf Klinz w imieniu grupy ALDE, Alain Lipietz w imieniu grupy Verts/ALE, Mario Borghezio w imieniu grupy UEN, Adamos Adamou w imieniu grupy GUE/NGL i Jens-Peter Bonde w imieniu grupy IND/DEM. Zgodnie z procedurą pytań z sali głos zabrali: Reinhard Rack, Monika Beňová, Olle Schmidt, Othmar Karas, Zita Pleštinská, Danutė Budreikaitė, Gerard Batten, Zsolt László Becsey, Antolín Sánchez Presedo i Zbigniew Zaleski. Głos zabrał Joaquín Almunia. 12. Zaostrzenie sytuacji w Gruzji (debata) Oświadczenia Rady i Komisji: Zaostrzenie sytuacji w Gruzji Janez Lenarčič (urzędujący przewodniczący Rady) i Benita Ferrero-Waldner (członkini Komisji) złożyli oświadczenia. Głos zabrali: Jacek Saryusz-Wolski w imieniu grupy PPE-DE, Hannes Swoboda w imieniu grupy PSE, Georgs Andrejevs w imieniu grupy ALDE, Marie Anne Isler Béguin w imieniu grupy Verts/ALE, Konrad Szymański w imieniu grupy UEN, Miloslav Ransdorf w imieniu grupy GUE/NGL, Ria Oomen-Ruijten, Jan Marinus Wiersma, Árpád Duka-Zólyomi, Józef Pinior, Charles Tannock, Alessandro Battilocchio, Corien Wortmann- Kool, Robert Evans i Vytautas Landsbergis. Zgodnie z procedurą pytań z sali głos zabrali: Urszula Gacek, Katrin Saks, Ewa Tomaszewska, Janusz Onysz- kiewicz, Tunne Kelam, Siiri Oviir i Zbigniew Zaleski. Głos zabrał Janez Lenarčič. PRZEWODNICTWO: Mechtild ROTHE Wiceprzewodnicząca Głos zabrała Benita Ferrero-Waldner. Złożone projekty rezolucji, które nie są jeszcze dostępne, zostaną ogłoszone w późniejszym terminie. Debata została zamknięta. Głosowanie: okres sesyjny czerwiec I. 13. Transatlantycka rada gospodarcza (debata) Oświadczenie Komisji: Transatlantycka rada gospodarcza Günter Verheugen (wiceprzewodniczący Komisji) złożył oświadczenie. -

Europäisches Parlament

EUROPÄISCHES PARLAMENT GGG G G G G 1999 G G 2004 G G G Plenarsitzungsdokument ENDGÜLTIG A5-0224/2004 2. April 2004 ***I ZWEITER BERICHT über den Vorschlag für eine Richtlinie des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates zur Harmonisierung der Rechts- und Verwaltungsvorschriften der Mitgliedstaaten über den Kredit an Verbraucher (KOM(2002) 0443 – C5-0420/2002 – 2002/0222(COD)) Ausschuss für Recht und Binnenmarkt Berichterstatter: Joachim Wuermeling RR\338483DE.doc PE 338.483 DE DE PR_COD_1am Erklärung der benutzten Zeichen * Verfahren der Konsultation Mehrheit der abgegebenen Stimmen **I Verfahren der Zusammenarbeit (erste Lesung) Mehrheit der abgegebenen Stimmen **II Verfahren der Zusammenarbeit (zweite Lesung) Mehrheit der abgegebenen Stimmen zur Billigung des Gemeinsamen Standpunkts Absolute Mehrheit der Mitglieder zur Ablehnung oder Abänderung des Gemeinsamen Standpunkts *** Verfahren der Zustimmung Absolute Mehrheit der Mitglieder außer in den Fällen, die in Artikel 105, 107, 161 und 300 des EG-Vertrags und Artikel 7 des EU-Vertrags genannt sind ***I Verfahren der Mitentscheidung (erste Lesung) Mehrheit der abgegebenen Stimmen ***II Verfahren der Mitentscheidung (zweite Lesung) Mehrheit der abgegebenen Stimmen zur Billigung des Gemeinsamen Standpunkts Absolute Mehrheit der Mitglieder zur Ablehnung oder Abänderung des Gemeinsamen Standpunkts ***III Verfahren der Mitentscheidung (dritte Lesung) Mehrheit der abgegebenen Stimmen zur Billigung des gemeinsamen Entwurfs (Die Angabe des Verfahrens beruht auf der von der Kommission vorgeschlagenen Rechtsgrundlage.) Änderungsanträge zu einem Legislativtext In den Änderungsanträgen werden Hervorhebungen in Fett- und Kursivdruck vorgenommen. Wenn Textteile mager und kursiv gesetzt werden, dient das als Hinweis an die zuständigen technischen Dienststellen auf solche Teile des Legislativtextes, bei denen im Hinblick auf die Erstellung des endgültigen Textes eine Korrektur empfohlen wird (beispielsweise Textteile, die in einer Sprachfassung offenkundig fehlerhaft sind oder ganz fehlen). -

Verzeichnis Der Abkürzungen

Verzeichnis der Abkürzungen APuZ Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte BCSV Badisch-Christlich-Soziale Volkspartei BHE Block (Bund) der Heimatvertriebenen und Entrechteten BP Bayernpartei BVerfG Bundesverfassungsgericht BVP Bayrische Volkspartei CDU Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands csu Christlich Soziale Union CVP Christliche Volkspartei DP Deutsche Partei DKP Deutsche Kommunistische Partei DNVP Deutschnationale Volkspartei DRP Deutsche Reichspartei DVP Deutsche Volkspartei DZP Deutsche Zentrumspartei EG Europäische Gemeinschaft EU Europäische Union EURATOM Europäische Atomgemeinschaft EVG Europäische Verteidigungsgemeinschaft FAZ Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung FDP Freie Demokratische Partei FR Frankfurter Rundschau GG Grundgesetz INFAS Institut ftir angewandte Sozialwissenschaft JÖR Jahrbuch des Öffentlichen Rechts der Gegenwart KPD Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands LDPD Liberaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands MP Ministerpräsident MPen Ministerpräsidenten 395 NPD Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands NZZ Neue Züricher Zeitung ÖVP Österreichische Volkspartei POS Partei des Demokratischen Sozialismus PVS Politische Vierteljahreszeitschrift RNZ Rhein-Neckar-Zeitung SBZ Sowjetische Besatzungszone SED Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands SPD Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands SPÖ Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs ssw Südschleswigscher Wählerverband sz Süddeutsche Zeitung Zentrum Deutsche Zentrumspartei ZParl Zeitschrift flir Parlamentsfragen 396 Tabellenverzeichnis Tabelle I: Einstellungen zur Auflösung von Landtagen -

4. Misja Powierzona Posłowi 5. Oficjalne Powitanie 6. Skład Komisji

C 27 E/2 Dziennik Urzędowy Unii Europejskiej PL 31.1.2008 Środa, 28 marca 2007 r. 4. Misja powierzona posłowi Przewodniczący poinformował, że premier Republiki Czeskiej poinformował go, iż nominował Jana Zahra- dila do reprezentowania go podczas konsultacji dotyczących deklaracji berlińskiej oraz, szerzej we wznowie- niu procesu konstytucyjnego w trakcie prezydencji niemieckiej Unii. Komisja Prawna, poproszona zgodnie z art. 4 ust. 5 Regulaminu o wydanie opinii, uznała na swoim posie- dzeniu w dniach 19 i 20 marca 2007 r., że misja jest zgodna z literą i duchem Aktu dotyczącego wyboru członków Parlamentu Europejskiego w powszechnych wyborach bezpośrednich oraz, że w związku z tym Jan Zahradil nie jest w sytuacji niezgodności i może wykonywać swój mandat poselski. 5. Oficjalne powitanie W imieniu Parlamentu Przewodniczący przywitał delegację z parlamentu irackiego, pod przewodnictwem Hamida Mousa, który zajął miejsce na trybunie honorowej. 6. Skład komisji i delegacji Przewodniczący otrzymał od grup PPE-DE, PSE, ALDE i posłów niezrzeszonych wnioski w sprawie nastę- pujących nominacji: — komisja AFET: Ria Oomen-Ruijten — komisja INTA: Corien Wortmann-Kool zamiast Alberta Jana Maata — komisja CONT: Ruth Hieronymi zamiast Vito Bonsignore — komisja REGI: Wolfgang Bulfon zamiast Giulietto Chiesa — komisja PECH: Joop Post zamiast Alberta Jana Maata — komisja JURI: Giulietto Chiesa zamiast Wolfganga Bulfona — komisja LIBE: Albert Jan Maat zamiast Ria Oomen-Ruijten — komisja FEMM: Albert Jan Maat zamiast CorienWortmann-Kool — komisja PETI: Gaya -

Download (515Kb)

European Community No. 26/1984 July 10, 1984 Contact: Ella Krucoff (202) 862-9540 THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT: 1984 ELECTION RESULTS :The newly elected European Parliament - the second to be chosen directly by European voters -- began its five-year term last month with an inaugural session in Strasbourg~ France. The Parliament elected Pierre Pflimlin, a French Christian Democrat, as its new president. Pflimlin, a parliamentarian since 1979, is a former Prime Minister of France and ex-mayor of Strasbourg. Be succeeds Pieter Dankert, a Dutch Socialist, who came in second in the presidential vote this time around. The new assembly quickly exercised one of its major powers -- final say over the European Community budget -- by blocking payment of a L983 budget rebate to the United Kingdom. The rebate had been approved by Community leaders as part of an overall plan to resolve the E.C.'s financial problems. The Parliament froze the rebate after the U.K. opposed a plan for covering a 1984 budget shortfall during a July Council of Ministers meeting. The issue will be discussed again in September by E.C. institutions. Garret FitzGerald, Prime Minister of Ireland, outlined for the Parliament the goals of Ireland's six-month presidency of the E.C. Council. Be urged the representatives to continue working for a more unified Europe in which "free movement of people and goods" is a reality, and he called for more "intensified common action" to fight unemployment. Be said European politicians must work to bolster the public's faith in the E.C., noting that budget problems and inter-governmental "wrangles" have overshadolted the Community's benefits. -

Association of Accredited Lobbyists to the European Parliament

ASSOCIATION OF ACCREDITED LOBBYISTS TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT OVERVIEW OF EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT FORUMS AALEP Secretariat Date: October 2007 Avenue Milcamps 19 B-1030 Brussels Tel: 32 2 735 93 39 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.lobby-network.eu TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction………………………………………………………………..3 Executive Summary……………………………………………………….4-7 1. European Energy Forum (EEF)………………………………………..8-16 2. European Internet Forum (EIF)………………………………………..17-27 3. European Parliament Ceramics Forum (EPCF………………………...28-29 4. European Parliamentary Financial Services Forum (EPFSF)…………30-36 5. European Parliament Life Sciences Circle (ELSC)……………………37 6. Forum for Automobile and Society (FAS)…………………………….38-43 7. Forum for the Future of Nuclear Energy (FFNE)……………………..44 8. Forum in the European Parliament for Construction (FOCOPE)……..45-46 9. Pharmaceutical Forum…………………………………………………48-60 10.The Kangaroo Group…………………………………………………..61-70 11.Transatlantic Policy Network (TPN)…………………………………..71-79 Conclusions………………………………………………………………..80 Index of Listed Companies………………………………………………..81-90 Index of Listed MEPs……………………………………………………..91-96 Most Active MEPs participating in Business Forums…………………….97 2 INTRODUCTION Businessmen long for certainty. They long to know what the decision-makers are thinking, so they can plan ahead. They yearn to be in the loop, to have the drop on things. It is the genius of the lobbyists and the consultants to understand this need, and to satisfy it in the most imaginative way. Business forums are vehicles for forging links and maintain a dialogue with business, industrial and trade organisations. They allow the discussions of general and pre-legislative issues in a different context from lobbying contacts about specific matters. They provide an opportunity to get Members of the European Parliament and other decision-makers from the European institutions together with various business sectors. -

Appendix to Memorandum of Law on Behalf of United

APPENDIX TO MEMORANDUM OF LAW ON BEHALF OF UNITED KINGDOM AND EUROPEAN PARLIAMENTARIANS AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER’S MOTION FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION LIST OF AMICI HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT OF THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND AND MEMBERS OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT House of Lords The Lord Ahmed The Lord Alderdice The Lord Alton of Liverpool, CB The Rt Hon the Lord Archer of Sandwell, QC PC The Lord Avebury The Lord Berkeley, OBE The Lord Bhatia, OBE The Viscount Bledisloe, QC The Baroness Bonham-Carter of Yarnbury The Rt Hon the Baroness Boothroyd, OM PC The Lord Borrie, QC The Rt Hon the Baroness Bottomley of Nettlestone, DL PC The Lord Bowness, CBE DL The Lord Brennan, QC The Lord Bridges, GCMG The Rt Hon the Lord Brittan of Spennithorne, QC DL PC The Rt Hon the Lord Brooke of Sutton Mandeville, CH PC The Viscount Brookeborough, DL The Rt Hon the Lord Browne-Wilkinson, PC The Lord Campbell of Alloway, ERD QC The Lord Cameron of Dillington The Rt Hon the Lord Cameron of Lochbroom, QC The Rt Rev and Rt Hon the Lord Carey of Clifton, PC The Lord Carlile of Berriew, QC The Baroness Chapman The Lord Chidgey The Lord Clarke of Hampstead, CBE The Lord Clement-Jones, CBE The Rt Hon the Lord Clinton-Davis, PC The Lord Cobbold, DL The Lord Corbett of Castle Vale The Rt Hon the Baroness Corston, PC The Lord Dahrendorf, KBE The Lord Dholakia, OBE DL The Lord Donoughue The Baroness D’Souza, CMG The Lord Dykes The Viscount Falkland The Baroness Falkner of Margravine The Lord Faulkner of Worcester The Rt Hon the -

European Parliament

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT ««« « « « « 1999 « « 2004 ««« Session document FINAL A5-0332/2001 11 October 2001 REPORT on the progress achieved in the implementation of the common foreign and security policy (C5-0194/2001 – 2001/2007(INI)) Committee on Foreign Affairs, Human Rights, Common Security and Defence Policy Rapporteur: Elmar Brok RR\451563EN.doc PE 302.047 EN EN PE 302.047 2/18 RR\451563EN.doc EN CONTENTS Page PROCEDURAL PAGE ..............................................................................................................4 MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION .............................................................................................5 EXPLANATORY STATEMENT............................................................................................11 RR\451563EN.doc 3/18 PE 302.047 EN PROCEDURAL PAGE At the sitting of 18 January 2001 the President of Parliament announced that the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Human Rights, Common Security and Defence Policy had been authorised to draw up an own-initiative report, pursuant to Rule 163 of the Rules of Procedure and with a view to the annual debate pursuant to Article 21 of the EU Treaty, on the progress achieved in the implementation of the common foreign and security policy). By letter of 4 May 2001 the Council forwarded to Parliament its annual report on the main aspects and basic choices of the CFSP, including the financial implications for the general budget of the European Communities; this document was submitted to Parliament pursuant to point H, paragraph 40, of the Interinstitutional Agreement of 6 May 1999 (7853/2001 – 2001/2007(INI)). At the sitting of 14 May 2001 the President of Parliament announced that she had referred this document to the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Human Rights, Common Security and Defence Policy as the committee responsible (C5-0194/2001). -

List of Members

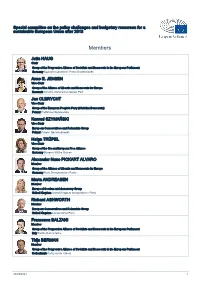

Special committee on the policy challenges and budgetary resources for a sustainable European Union after 2013 Members Jutta HAUG Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Germany Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands Anne E. JENSEN Vice-Chair Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Denmark Venstre, Danmarks Liberale Parti Jan OLBRYCHT Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska Konrad SZYMAŃSKI Vice-Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Helga TRÜPEL Vice-Chair Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Bündnis 90/Die Grünen Alexander Nuno PICKART ALVARO Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Germany Freie Demokratische Partei Marta ANDREASEN Member Europe of freedom and democracy Group United Kingdom United Kingdom Independence Party Richard ASHWORTH Member European Conservatives and Reformists Group United Kingdom Conservative Party Francesca BALZANI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Thijs BERMAN Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Netherlands Partij van de Arbeid 26/09/2021 1 Reimer BÖGE Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands José BOVÉ Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance France Europe Écologie Michel DANTIN Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) France Union pour un Mouvement Populaire Jean-Luc DEHAENE Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Belgium Christen-Democratisch & Vlaams Albert DESS Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich-Soziale Union in Bayern e.V. -

11. Explanations of Vote 12. Corrections to Votes

C 77 E/90 Official Journal of the European Union EN 26.3.2004 Wednesday 24 September 2003 11. Explanations of vote Written explanations of vote: Explanations of vote submitted in writing under Rule 137(3) appear in the verbatim report of proceedings for this sitting. Oral explanations of vote: Report McCarthy A5-0238/2003: Nuala Ahern, Brian Crowley, Hiltrud Breyer, Jean-Maurice Dehousse, Daniela Raschhofer Report Jonckheer A5-0302/2003: Agnes Schierhuber Report Andersson A5-0259/2003: Carlo Fatuzzo, Francesco Enrico Speroni Report Gil-Robles Gil-Delgado and Tsatsos A5-0299/2003: Carles-Alfred Gasòliba i Böhm, Jean-Maurice Dehousse, Bernd Posselt, Francesco Enrico Speroni, Robert Goebbels 12. Corrections to votes Corrections to votes were submitted by the following Members: Report Brok A5-0306/2003 amendment 10 for: Paul Coûteaux, Fodé Sylla against: Marie Anne Isler Béguin, Lissy Gröner, W.G. van Velzen amendment 4 for: Fodé Sylla abstention: Walter Veltroni, Philip Claeys, Koenraad Dillen recommendation against: Fodé Sylla abstention: Geneviève Fraisse Report McCarthy A5-0238/2003 amendments 52, 54/rev and 68 (identical) against: Christa Klaß amendment 69 for: Klaus Hänsch, Marie-Thérèse Hermange, Olga Zrihen, Othmar Karas against: Hans-Gert Poettering, Godelieve Quisthoudt-Rowohl amendments 55/rev, 97 and 108 (identical) for: Marie Anne Isler Béguin, Pervenche Berès, Hubert Pirker, Olga Zrihen article 4, paragraph 1 amendment 16 cp against: Béatrice Patrie, Bernard Poignant, Othmar Karas, Michel Rocard article 4, paragraph -

European Parliament Minutes En En

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 2006 - 2007 MINUTES of the sitting of Tuesday 16 January 2007 P6_PV(2007)01-16 PE 382.953 EN EN KEYS TO SYMBOLS USED * Consultation procedure ** I Cooperation procedure: first reading ** II Cooperation procedure: second reading *** Assent procedure ***I Codecision procedure: first reading ***II Codecision procedure: second reading ***III Codecision procedure: third reading (The type of procedure is determined by the legal basis proposed by the Commission) INFORMATION RELATING TO VOTING TIME Unless stated otherwise, the rapporteurs informed the Chair in writing, before the vote, of their position on the amendments. ABBREVIATIONS USED FOR PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEES AFET Committee on Foreign Affairs DEVE Committee on Development INTA Committee on International Trade BUDG Committee on Budgets CONT Committee on Budgetary Control ECON Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs EMPL Committee on Employment and Social Affairs ENVI Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety ITRE Committee on Industry, Research and Energy IMCO Committee on the Internal Market and Consumer Protection TRAN Committee on Transport and Tourism REGI Committee on Regional Development AGRI Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development PECH Committee on Fisheries CULT Committee on Culture and Education JURI Committee on Legal Affairs LIBE Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs AFCO Committee on Constitutional Affairs FEMM Committee on Women's Rights and Gender Equality PETI Committee on Petitions ABBREVIATIONS USED FOR POLITICAL GROUPS PPE-DE Group of the European People’s Party (Christian Democrats) and European Democrats PSE Socialist Group in the European Parliament ALDE Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe UEN Union for Europe of the Nations Group Verts/ALE Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance GUE/NGL Confederal Group of the European United Left – Nordic Green Left IND/DEM Independence and Democracy Group ITS Identity, Tradition and Sovereignty Group NI Non-attached Members Contents 1.