Izydora Dąmbska SYMBOL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorandum of the Secretariat General on the European Flag Pacecom003137

DE L'EUROPE - COUNCIL OF EDMFE Consultative Assembly Confidential Strasbourg,•15th July, 1951' AS/RPP II (3) 2 COMMITTEE ON RULES OF PROCEDURE AND PRIVILEGES Sub-Committee on Immunities I MEMORANDUM OF THE SECRETARIAT GENERAL ON THE EUROPEAN FLAG PACECOM003137 1.- The purpose of an Emblem There are no ideals, however exalted in nature, which can afford to do without a symbol. Symbols play a vital part in the ideological struggles of to-day. Ever since there first arose the question of European, organisation, a large number of suggestions have more particularly been produced in its connection, some of which, despite their shortcomings, have for want of anything ;. better .been employed by various organisations and private ' individuals. A number of writers have pointed out how urgent and important it is that a symbol should be adopted, and the Secretariat-General has repeatedly been asked to provide I a description of the official emblem of the Council of Europe and has been forced to admit that no such emblem exists. Realising the importance of the matter, a number of French Members of Parliament^ have proposed in the National Assembly that the symbol of the European Movement be flown together with the national flag on public buildings. Private movements such as'the Volunteers of Europe have also been agitating for the flying of the European Movement colours on the occasion of certain French national celebrations. In Belgium the emblem of the European Movement was used during the "European Seminar of 1950" by a number of *•*: individuals, private organisations and even public institutions. -

16088-Chars-For-Emoji-Provisional.Pdf

Characters Proposed for Emoji=Provisional To: UTC From: Emoji Subcommittee Date: 2016-04-21 Emoji_ Emoji_ Emoji_ Code Name Char LG Microsoft Samsung Presentation Modifier_Base Direction_Base U+2605 BLACK STAR ★ Provisional U+2607 LIGHTNING ☇ Provisional U+2608 THUNDERSTORM ☈ Provisional U+2609 SUN ☉ Provisional U+260A ASCENDING NODE ☊ Provisional U+260B DESCENDING NODE ☋ Provisional U+260C CONJUNCTION ☌ Provisional U+260D OPPOSITION ☍ Provisional U+260F WHITE TELEPHONE ☏ Provisional U+2610 BALLOT BOX ☐ Provisional U+2612 BALLOT BOX WITH X ☒ Provisional U+2616 WHITE SHOGI PIECE ☖ Provisional U+2617 BLACK SHOGI PIECE ☗ Provisional U+2619 REVERSED ROTATED FLORAL HEART BULLET ☙ Provisional 1 U+261A BLACK LEFT POINTING INDEX ☚ Provisional U+261B BLACK RIGHT POINTING INDEX ☛ Provisional U+261C WHITE LEFT POINTING INDEX ☜ Provisional Provisional U+261E WHITE RIGHT POINTING INDEX ☞ Provisional Provisional U+261F WHITE DOWN POINTING INDEX ☟ Provisional Provisional U+2621 CAUTION SIGN ☡ Provisional U+2624 CADUCEUS ☤ Provisional U+2625 ANKH ☥ Provisional U+2627 CHI RHO ☧ Provisional U+2628 CROSS OF LORRAINE ☨ Provisional U+2629 CROSS OF JERUSALEM ☩ Provisional U+262B FARSI SYMBOL ☫ Provisional U+262C ADI SHAKTI ☬ Provisional U+262D HAMMER AND SICKLE ☭ Provisional U+263B BLACK SMILING FACE ☻ Provisional U+263C WHITE SUN WITH RAYS ☼ Provisional U+263D FIRST QUARTER MOON ☽ Provisional U+263E LAST QUARTER MOON ☾ Provisional U+263F MERCURY ☿ Provisional 2 U+2640 FEMALE SIGN ♀ Provisional U+2641 EARTH ♁ Provisional U+2642 MALE SIGN ♂ Provisional U+2643 -

The Merovingian Dynasty with Their King Dagobert II Presents An

On an article by Tracy R Twyman To read Tracy R Twyman’s full article, please refer to the internet. The Merovingian dynasty with their king Dagobert II presents an important spiritual link between Jesus Christ and the Cathar endeavour to restore genuine Christianity a few centuries later. The history of the Merovingian dynasty spans the history of human kind. Just as the dynasty was at the shaping of World’ events, so World’s events shaped the dynasty’s fate. The first phase of humanity has concluded and the Merovingian story stands as the archetype of societal evolution reflected through a significant blood line. The Cathar Testament explains the principles in theory, whilst focusing on the Soul. Using an article by Tracy R. Twyman, I have pinpointed some of the pivotal stages against the Merovingian story traced through legends from the times of Atlantis. My comments do not represent the views of Tracy R Twyman. The adaptation is a working tool for students of the Cathar Testament. My comments are in brackets. To read Tracy R Twyman’s full article, please refer to the internet. Corascendea 17.03.2013. The Myth: The Frankish King Dagobert II, and the Merovingian dynasty from which he came, have been romantically mythologized in the annals of both legend and mystical pseudo-history. The mystique that surrounds them includes attributions of divine origin from Atlantis. They were described as the descendants of Mary Magdalene and Jesus Christ, while legends talk of their powers, even of the magical powers of their regalia. The Merovingian race originated with a civilization far more ancient than recorded history, from which came all of the major arts and sciences. -

Guide to Saints and Symbols in Stained Glass

Guide to Saints and Symbols in Stained Glass In churches and chapels, stained glass windows help create the sense of a sacred space. Stained glass windows of the saints can provide worshipers with inspirational illustrations of the venerated. The various saints may be depicted in stained glass either symbolically or in scenes from their lives. One of the challenges facing church designers, building committees and pastors doing church construction or remodeling is finding the right stained Saint Matthew Saint Mark glass images for your church or chapel. Panel #1001 Panel #1000 To help you, Stained Glass Inc. offers the largest selection of stained glass in the world. You will find Stained Glass Inc. windows to be of the finest quality, affordable and custom made to the size and shape of your window. If your church or organization is looking for a stained glass window of a saint, we can help. Not all the saints are listed here. If you are looking for a particular saint and you don’t find him or her listed here, just contact us, we can create a stained glass artwork for you. Saint Luke Saint John Panel #1005 Panel #1006 4400 Oneal, Greenville, TX • Phone: (903) 454-8376 [email protected] • www.StainedGlassInc.com To see more Saints in stained glass, click here: http://stainedglassinc.com/religious/saints-and-angels/saints.html The following is a list of the saints and their symbols in stained glass: Saint Symbol in Stained Glass and Art About the Saint St. Acathius may be illustrated in Bishop of Melitene in the third century. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 4.1 This File Contains an Excerpt from the Character Code Tables and List of Character Names for the Unicode Standard, Version 4.1

Miscellaneous Symbols Range: 2600–26FF The Unicode Standard, Version 4.1 This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 4.1. Characters in this chart that are new for The Unicode Standard, Version 4.1 are shown in conjunction with any existing characters. For ease of reference, the new characters have been highlighted in the chart grid and in the names list. This file will not be updated with errata, or when additional characters are assigned to the Unicode Standard. See http://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See http://www.unicode.org/Public/4.1.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 4.1. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the on-line reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 4.1 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this excerpt file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 4.1, at http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode4.1.0/, including sections unchanged in The Unicode Standard, Version 4.0 (ISBN 0-321-18578-1), as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, and #34, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available on-line. See http://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and http://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

The Migration of an Emblem Through the Example of the Cross of Burgundy

The migration of an emblem through the example of the cross of Burgundy by Patrice de La Condamine Abstract The choice for the subject of this paper, The migration of an emblem through the example of the cross of Burgundy, needs an explanation. The purpose of this subject is double. The first one, as the first part of the title indicates, is to show the migration of the emblems, showing that they follow the movements of populations. The second purpose is to explain this reality through an example: the cross of Burgundy. This choice seems to be all the more appropriate since the country which welcomes us was one of the first to receive this emblem on its ter - ritory, in historic circumstances that everybody knows. The story could begin with Once upon a time, there was a cross... The Burgundian native land I do not pretend to know everything about the origins of the cross of Burgundy, how - ever I can talk about its history. First, its name ‘Cross of Burgundy’ does not let any doubt 1 about its origin: Burgundy, the actual region situated in the east of France. On the graphic aspect, it’s a saltirewise cross, called a Saint-Andrew’s cross 2, which is particular, as on the edges of its four limbs some small branch-like offshoots from the main cross can be noticed. That is why this emblem is also called “croix écotée”, 6 in The saltire of Burgundy French. Originally, it represented two crossed tree trunks of which the branches had been cut off, so that only the sawn-off ends remained. -

The Brill Typeface User Guide & Complete List of Characters

The Brill Typeface User Guide & Complete List of Characters Version 2.06, October 31, 2014 Pim Rietbroek Preamble Few typefaces – if any – allow the user to access every Latin character, every IPA character, every diacritic, and to have these combine in a typographically satisfactory manner, in a range of styles (roman, italic, and more); even fewer add full support for Greek, both modern and ancient, with specialised characters that papyrologists and epigraphers need; not to mention coverage of the Slavic languages in the Cyrillic range. The Brill typeface aims to do just that, and to be a tool for all scholars in the humanities; for Brill’s authors and editors; for Brill’s staff and service providers; and finally, for anyone in need of this tool, as long as it is not used for any commercial gain.* There are several fonts in different styles, each of which has the same set of characters as all the others. The Unicode Standard is rigorously adhered to: there is no dependence on the Private Use Area (PUA), as it happens frequently in other fonts with regard to characters carrying rare diacritics or combinations of diacritics. Instead, all alphabetic characters can carry any diacritic or combination of diacritics, even stacked, with automatic correct positioning. This is made possible by the inclusion of all of Unicode’s combining characters and by the application of extensive OpenType Glyph Positioning programming. Credits The Brill fonts are an original design by John Hudson of Tiro Typeworks. Alice Savoie contributed to Brill bold and bold italic. The black-letter (‘Fraktur’) range of characters was made by Karsten Lücke. -

Proposal to Encode the Typikon Symbols in Unicode

PONOMAR PROJECT Proposal to Encode the Typikon Symbols in Unicode Yuri Shardt, Aleksandr Andreev L2/09-310 L2/09-310 1 In Church Slavonic documents, for example, in the Orthodox Typikon, one encounters 4 common symbols that are used designate the rank of an ecclesiastical commemoration. Depending on the publisher and local convention, these symbols can be placed within the text or in the margins. Since these symbols are often found in Slavonic Church books, these symbols will be encoded in the “Extended Cyrillic Block B” of the Unicode standard. Based on the information in Chapter 47 of the Orthodox Typikon ( (Тѷпікон сіесть´ Ѹ҆ставъ (Tipikon siject' Ustav), 1954), (Тѷпікон сіесть´ Ѹ҆ставъ (Tipikon sijest' Ustav), 1965)) and local convention, the desired symbols, their characteristics, and proposed encoding region are described in Table 1. Two examples of Chapter 47 of the Typikon are presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2. As well, extracts from the Orthodox Menologion, where theses symbols are used to rank the commemorations, are given in Figure 3 and Figure 4. As can be seen from the sample publications, these symbols can occur anywhere in the line. Table 1: Summary of the Proposed Typikon Symbols for Encoding Typical Typikon Proposed Name Proposed Location Comments Symbol Typikon Symbol U + A674 The cross need not be Great Feast the same as the cross in the Typikon ⛐ Symbol Polyeleos. Typikon Symbol Vigil U + A675 The cross need not be Service the same as the cross in the Typikon ⛑ Symbol Polyeleos. Typikon Symbol U + A676 This symbol can be Polyeleos similar to U + 2722 (Four teardrop-spoked ⛒ asterisk). -

The Unicode Standard 5.2 Code Charts

Miscellaneous Symbols Range: 2600–26FF The Unicode Standard, Version 5.2 This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 5.2. Characters in this chart that are new for The Unicode Standard, Version 5.2 are shown in conjunction with any existing characters. For ease of reference, the new characters have been highlighted in the chart grid and in the names list. This file will not be updated with errata, or when additional characters are assigned to the Unicode Standard. See http://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See http://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-5.2/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 5.2. See http://www.unicode.org/Public/5.2.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 5.2. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 5.2 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 5.2, online at http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode5.2.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, and #44, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. -

Emoji and Symbol Additions - Religious Symbols and Structures

Emoji and Symbol Additions - Religious Symbols and Structures To: UTC Date: 19 October 2014 From: Shervin Afshar (HighTech Passport, Ltd.), Roozbeh Pournader (Google Inc.) Live Doc: http://goo.gl/pz5a00 As a follow-up to previously submitted documents to UTC, L2/14-1721 and L2/14-174R2, this document proposes a set of eight additional characters representing religious symbols and structures for incorporation into Unicode. Contents Contents Current State Objective and Selection Criteria Major Belief Systems According to Statistics Encoding Models for Symbols for Religious Structures Proposed Symbols Other Symbols Considered Discussion Character Properties Appendix 1: Current Religious Symbols in Unicode Appendix 2: Common Religious Map Symbols Bibliography Current State There are numerous religious symbols already incorporated into Unicode. Among those some may qualify as emoji. See the chart in Appendix 1. Symbols for church (U+26EA) and Shinto 1 Edberg, and Davis. “Proposed enhancements for emoji characters: background”. 2 Edberg, and Davis. “Emoji Additions”. 1 shrine (U+26E9) already exist in Unicode and have emoji usage. Objective and Selection Criteria The objective has been to have symbols and structures of major belief systems worldwide represented with an emphasis on filling up existing gaps in the encoded symbol repertoire (e.g. for those major belief systems with specific, strong focus on places of worship as centers of community3). 4 Major Belief Systems According to Statistics Statistics reported are percentages of global population: ● Pew Research Center5 (2012) statistics are: Christianity (31.5%), Islam (23.2%), Unaffiliated (16.3%), Hinduism (15.0%), Buddhism (7.1%), Folk religions (5.9%), Other (0.8%), Judaism (0.2%). -

Number 1 January 2010 Volume

VOLUME LVI JANUARY 2010 NUMBER 1 ZWALLET_KT0110:Layout 1 11/13/09 11:18 AM Page 1 EXCLUSIVELY DESIGNED FOR SIR KNIGHTS York Rite Security Wallet A Useful Accessory and Daily Reminder of Your Fraternity Actual size is 2 3/4" X 4 1/4" closed. We proudly present our genuine leather for security. Also suitable to hold small zippered security wallet, with our Official cell phones. Fits neatly in your pant or Chapter, Council & Commandery York jacket pocket. Rite Emblem, minted like a fine coin and Order several for yourself and as gifts for displayed on the front flap fellow Sir Knights. You have earned The unique ultra-thin design features the right to own this York Rite wallet. convenient exterior slots for credit cards, It is not sold in stores and is available insurance and ID’s. Interior with additional only through this announcement. Your card slots, window display and stretch band satisfaction is guaranteed or return within to secure currency is completely zippered 30 days for replacement or refund. CALL TOLL-FREE TO ORDER: 1-800-437-0804 MON - FRI 9AM - 5PM EST. PLEASE HAVE CREDIT CARD READY WHEN ORDERING. Mail To: York Rite Masonic Order Center, SHIPPING ADDRESS: (Sorry, we cannot ship to P.O. Boxes) Two Radnor Corporate Center, Suite 120, Radnor, PA 19087 YES, I wish to order _____ (Qty) York Rite leather security wallet(s) Name: ______________________________________ at $29.95* each. Address: ____________________________________ I PREFER TO PAY AS FOLLOWS: I enclose my check or money order for $______as payment in full, OR City: ____________________ State: ____ Zip: ________ Charge my credit card $______, as follows: Phone: (_________)____________________________ Credit Card: Visa MasterCard AMEX Discover Card # _______________________ Exp. -

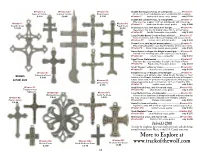

To Explore At

#Pewter-LC #Pewter-LCT #Pewter-FC Double Bar Iroquois Cross, of solid pewter ................#Pewter-IC Cross of Lorraine Cross of Lorraine Flower Cross Circle, tear, heart and diamond pierced. Christian fish markings. $ 4.00 $ 9.99 $ 5.25 #Pewter-IC double bar Iroquois cross, pewter only $10.99 Double Bar Lorraine Cross, of solid pewter ...............#Pewter-LC This tiny cross is about 1-1/2” tall. Solid pewter with loop at top. #Pewter-IC #Pewter-PC #Pewter-LC double bar Lorraine cross, pewter only $ 4.00 Iroquois Cross Papal Cross $10.99 $ 6.99 Arabesque Cross, with decorative designs .............. #Pewter-AC Decorated in the fanciful Arabian style, with no animal figures. #Pewter-AC fanciful Arabesque cross, pewter only $ 3.99 Large Double-barred Lorraine Cross with tail ........ #Pewter-LCT Cross of Lorraine, with embossed markings, and a crescent tail. #Pewter-LCT Lorraine cross, with tail, pewter only $ 9.99 Flower Cross, with basket weave pattern...................#Pewter-FC This small solid pewter cross has five flowers, at ends and center. #Pewter-FC flower cross, basket weave, pewter only $ 5.25 Sword Cross, in shape of a Knight’s sword grip ...... #Pewter-SC A small cross of solid pewter, with embossed circle designs. #Pewter-SC sword cross, solid pewter only $ 4.50 Papal Cross, triple-barred ........................................... #Pewter-PC This three bar cross resembles the staff of the Pope in Rome. #Pewter-PC Papal cross, three bars, pewter only $ 6.99 Small “Rosace” or Rosary Cross ............................... #Pewter-RC #Pewter-RC Rosace cross, solid pewter only $ 6.99 #Pewter-AC Templier Cross of “Knights of the Temple” ................#Pewter-TC Shown Arabesque Cross A religious and military order called Knight Templars or Poor $ 3.99 Soldiers of the Temple, founded in Jerusalem on the site of Soloman’s actual size #Pewter-SC temple about 1118, for protection of pilgrims and the Holy Sepulcher.