Alternative Report to the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (Cerd)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools JUL 0 2 2003

Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools By Mahjabeen Quadri B.S. Architecture Studies University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2001 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2003 JUL 0 2 2003 Copyright@ 2003 Mahjabeen Quadri. Al rights reserved LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: Mahjabeen Quadri Departm 4t of Architecture, May 19, 2003 Certified by:- Reinhard K. Goethert Principal Research Associate in Architecture Department of Architecture Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Julian Beinart Departme of Architecture Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students ROTCH Thesis Committee Reinhard Goethert Principal Research Associate in Architecture Department of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Edith Ackermann Visiting Professor Department of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Anna Hardman Visiting Lecturer in International Development Planning Department of Urban Studies and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Hashim Sarkis Professor of Architecture Aga Khan Professor of Landscape Architecture and Urbanism Harvard University Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools By Mahjabeen Quadri Submitted to the Department of Architecture On May 23, 2003 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies Abstract Pakistan's greatest resource is its children, but only a small percentage of them make it through primary school. -

Muslim Saints of South Asia

MUSLIM SAINTS OF SOUTH ASIA This book studies the veneration practices and rituals of the Muslim saints. It outlines the principle trends of the main Sufi orders in India, the profiles and teachings of the famous and less well-known saints, and the development of pilgrimage to their tombs in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. A detailed discussion of the interaction of the Hindu mystic tradition and Sufism shows the polarity between the rigidity of the orthodox and the flexibility of the popular Islam in South Asia. Treating the cult of saints as a universal and all pervading phenomenon embracing the life of the region in all its aspects, the analysis includes politics, social and family life, interpersonal relations, gender problems and national psyche. The author uses a multidimen- sional approach to the subject: a historical, religious and literary analysis of sources is combined with an anthropological study of the rites and rituals of the veneration of the shrines and the description of the architecture of the tombs. Anna Suvorova is Head of Department of Asian Literatures at the Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow. A recognized scholar in the field of Indo-Islamic culture and liter- ature, she frequently lectures at universities all over the world. She is the author of several books in Russian and English including The Poetics of Urdu Dastaan; The Sources of the New Indian Drama; The Quest for Theatre: the twentieth century drama in India and Pakistan; Nostalgia for Lucknow and Masnawi: a study of Urdu romance. She has also translated several books on pre-modern Urdu prose into Russian. -

The Land of Five Rivers and Sindh by David Ross

THE LAND OFOFOF THE FIVE RIVERS AND SINDH. BY DAVID ROSS, C.I.E., F.R.G.S. London 1883 Reproduced by: Sani Hussain Panhwar The land of the five rivers and Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 TO HIS EXCELLENCY THE MOST HONORABLE GEORGE FREDERICK SAMUEL MARQUIS OF RIPON, K.G., P.C., G.M.S.I., G.M.I.E., VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, THESE SKETCHES OF THE PUNJAB AND SINDH ARE With His Excellency’s Most Gracious Permission DEDICATED. The land of the five rivers and Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 PREFACE. My object in publishing these “Sketches” is to furnish travelers passing through Sindh and the Punjab with a short historical and descriptive account of the country and places of interest between Karachi, Multan, Lahore, Peshawar, and Delhi. I mainly confine my remarks to the more prominent cities and towns adjoining the railway system. Objects of antiquarian interest and the principal arts and manufactures in the different localities are briefly noticed. I have alluded to the independent adjoining States, and I have added outlines of the routes to Kashmir, the various hill sanitaria, and of the marches which may be made in the interior of the Western Himalayas. In order to give a distinct and definite idea as to the situation of the different localities mentioned, their position with reference to the various railway stations is given as far as possible. The names of the railway stations and principal places described head each article or paragraph, and in the margin are shown the minor places or objects of interest in the vicinity. -

Beliefs and Behaviors of Shrine Visitors of Bibi Pak Daman

Journal of Gender and Social Issues Spring 2020, Vol. 19, Number 1 ©Fatima Jinnah Women University, Rawalpindi Beliefs and Behaviors of Shrine Visitors of Bibi Pak Daman Abstract The present study aims at focusing on what kind of beliefs are associated with the shrine visits that make them visitors believe and behave in a specific way. The shrine selected for this purpose was Bibi Pak Daman, Lahore, Pakistan. The visitors of this shrine were observed using non- participant observation method. Field notes were used to record observations and the data were analyzed using thematic analysis. Three major themes emerged out of the data. The first major theme of immortality appeared with sub-themes of belief in existence after death, belief in supernatural powers of chaste ladies and objects placed at the shrine. The second theme that emerged consisted of superstitions with the sub-themes of superstitions related to objects and miracles/mannat system. The third theme that emerged was of the beliefs in the light of the placebo effect and the sub-themes included prayer fulfillment, enhanced spirituality and problem resolution. Keywords: Bibi Pak Daman, beliefs, shrine visitors INTRODUCTION Islam has a unique role in meeting the spiritual needs of its followers through Sufism, which is defined as a system of beliefs wherein Muslims search for their spiritual knowledge in the course of direct personal experience and practice of Allah Almighty (Khan & Sajid, 2011). Sufism represents the spiritual dimension of Islam. Sufis played a major role in spreading Islam throughout the sub-continent, sometimes even more than the warriors. In early 12th century, Sufi saints connected the Hindus and Muslims with their deep devotion and love for God as the basic tenet of belief. -

Kurrachee (Karachi) Past: Present and Future

KURRACHEE (KARACHI) PAST: PRESENT AND FUTURE ALEXANDER F. BAILLIE, F.R.G.S., 1880 BIRD'S EYE VIEW OF VICTORIA ROAD CLERK STREET, SADDAR BAZAR KARACHI REPRODUCED BY SANI H. PANHWAR (2019) KUR R A CH EE: PA ST:PRESENT:A ND FUTURE. KUR R A CH EE: (KA R A CH I) PA ST:PRESENT:A ND FUTURE. BY A LEXA NDER F.B A ILLIE,F.R.G.S., A uthor of"A PA RA GUA YA N TREA SURE,"etc. W ith M a ps,Pla ns & Photogra phs 1890. Reproduced by Sa niH .Panhw a r (2019) TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE SIR MOUNTSTUART ELPHINSTONE GRANT-DUFF, P.C., G.C.S.I., C.I.E., F.R.S., M.R.A.S., PRESIDENT OF THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY, FORMERLY UNDER-SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INDIA, AND GOVERNOR OF THE PROVINCE OF MADRAS, ETC., ETC., THIS ACCOUNT OF KURRACHEE: PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE, IS MOST RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY HIS OBEDIENT SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. INTRODUCTION. THE main objects that I have had in view in publishing a Treatise on Kurrachee are, in the first place, to submit to the Public a succinct collection of facts relating to that City and Port which, at a future period, it might be difficult to retrieve from the records of the Past ; and secondly, to advocate the construction of a Railway system connecting the GateofCentralAsiaand the Valley of the Indus, with the Native Capital of India. I have elsewhere mentioned the authorities to whom I am indebted, and have gratefully acknowledged the valuable assistance that, from numerous sources, has been afforded to me in the compilation of this Work; but an apology is due to my Readers for the comments and discursions that have been interpolated, and which I find, on revisal, occupy a considerable number of the following pages. -

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES and MONUMENTS in SINDH PROVINCE PROTECTED by the FEDERAL GOVERNMENT Badin District 1

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES AND MONUMENTS IN SINDH PROVINCE PROTECTED BY THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT Badin District 1. Runs of old city at Badin, Badin Dadu District 2. Tomb of Yar Muhammad Khan kalhora and its adjoining Masjid near khudabad, Dadu. 3. Jami Masjid, Khudabad, Dadu. 4. Rani Fort Kot, Dadu. 5. Amri, Mounds, Dadu. 6. Lakhomir-ji-Mari, Deh Nang opposite Police outpost, Sehwan, Dadu. 7. Damb Buthi, Deh Narpirar at the source of the pirari (spring), south of Jhangara, Sehwan, Dadu. 8. Piyaroli Mari, Deh Shouk near pir Gaji Shah, Johi, Dadu. 9. Ali Murad village mounds, Deh Bahlil Shah, Johi, Dadu. 10. Nasumji Buthi, Deh Karchat Mahal, Kohistan, Dadu. 11. Kohtrass Buthi, Deh Karchat about 8 miles south-west of village of Karchat on road from Thana Bula Khan to Taung, Dadu. 12. Othamjo Buthi Deh Karchat or river Baran on the way from the Arabjo Thano to Wahi village north-west of Bachani sandhi, Mahal, Kohistan, Dadu. 13. Lohamjodaro, Deh Palha at a distance of 30 chains from Railway Station but not within railway limits, Dadu. 14. Pandhi Wahi village mounds, Deh Wahi, Johi, Dadu. 15. Sehwan Fort, Sehwan, Dadu. 16. Ancient Mound, Deh Wahi Pandhi, Johi, Dadu. 17. Ancient Mound, Deh Wahi Pandhi, Johi, Dadu. Hyderabad District 18. Tomb of Ghulam Shah Kalhora, Hyderabad. 19. Boundary Wall of Pucca Fort, Hyderabad. 20. Old office of Mirs, Hyderabad Fort, Hyderabad. 21. Tajar (Treasury) of Mirs, Hyderabad Fort, Hyderabad. 22. Tomb of Ghulam Nabi Khan Kalhora, Hyderabad. 23. Buddhist Stupa, (Guja) a few miles from Tando Muhammad Khan, Hyderabad. 24. -

Download Map (PDF | 1.89

Panjpai P a k i s t a Maamuri n Kinjar Khas Shikh Wasil Kolpur Kohlu Barkhan Mach Sangan Shujaabad Kot Chutta Khangarh Basti Maluk Jhok Utara Dunyapur Rohilanwali !(H ! ! ! Mall Nau ! Kotla Band Ali * Dirao # ! Mithri Alipur ! Alipur ! ! ! Kalanpur ! ! ! Hajipur Sikhaniwala ! ! ! Manguuchar !( ! ! * # Khairpur Sadat Panjnad ! Johan Nari Bolan Dam Haji Terhi! ! Fazilpur !! Kahan Margand ! ! ! ! ! Bibargi o ! Uch! ! Kotla ! ! ! RAJANPUR ! Kundai! Sitpur ! Dad Uch Lahri ! ! NORTHWEST ! Bhalla JhallManoghla Khairwah Nanshahra !Hatkari ! ! Basti Khor 67°E 67°30'E Chhamb SachuBabar Ahmad Khan 68°E 68°30'E 69°E 69°30'E 7!0°E 70°30'E ! 71°AEli Muhammad ! ! ! ! Sabzal Kot Rajanpur Aqilpur MUZAFFARGARH! Ahmad Yar !( ! ! ! ! Bent Sauntra Bakhshu Banhar Khan ! ! ! Kulab ! Pir Jongal ! Bangzila! ! ! Katbar Karam Thul Nurpur Tarind Muhammad Panah ! Goth Rais ! Kohing ! Dera Bugti ! Mian ! Bazdan Abra ! ! Ahmad Ali Lar !( ! Bhag ! ! ! Kalat KALAT ! Asni Foliji Kotla 29°N BOLAN SIBI ! Janpur 29°N Rahim ! Lahna Loti Allahabad ! ! Wazira ! ! Tuziani ! ! ! ! Chalgari ! Lanjewala Kot ! Gazo ! Chaudhari ! Mahmud Aulia ! ! Sanhri Murghai Mithankot Chandni ! ! ! ! Chacharan ! Bughia ! Dilbar Abdullah Shaheed ! Matela D. G. KHAN ! ! Shoran Rahmanpur Chhatr Saleh Mahar Basti ! ! ! ! DERA BUGTI ! RAJANUPmUarRkot Ghanspur Gandoi Chauki ! ! Jam Ghulam Rasul ! ! ! ! Nichera Basti Basti Haji ! Chak ! ! Khuddi Fateh Muhammad ! Bahram Khan Ramdani Nawab Khan! Badh Machhi Imam Bakhsh ! Quraishi ! ! ! ! Nuttal Bandowali Rukkanpur !Basti ! Moinabad ! Feroza ! Shahpur ! -

Sindhu Jii Sanjah

G M Syed Sindhudesh A Study In Its Separate Identity Through The Ages (Translation of "Sindhu Ji Saanjah" in Sindhi) PREFACE A considerable span of my life remained in search of Islam, its precepts and practice. Also, while playing a significant role in my country's politics, 1, at times, pondered over the socioeconomic and socio-political problems of our beloved Sindh. My feelings, experiences, knowledge and research on these matters have already been expressed from time to time on different occasions in various publications. On our country's politics, my contributions were published entitled (i) "BIRDS EYE VIEW ON PAKISTAN'S PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE"; (ii) "SINDHU DESH WHY AND WHAT FOR?" [For full text...click here] On religion the other two works (i) "RELIGION AND REALITY" [For full text...click here] and (ii) "ON THE PATH OF MY BELOVED" are worth mentioning. Who-so- ever has read these books, may easily understand the evolution of my approach towards politics and religion. Now, owing to my old age, I am afraid, I will not be in a position to write any more on these subjects separately. So, in this book, I deem it necessary to assimilate the facts and figures summarily. Hoping this may serve to the readers about the crux of the problem aiming at its remedy, which of course, is now the sole objective of my life. SINDHU DESH is that part of the Indian Subcontinent to It's Nature has entrusted from time immemorial a vast area of rich and cultivable land, with plenty of water flowing in the river Indus as also, with a bounty of long seashore, which enabled the natives of this land to acquire a rich heritage of refined culture and civilization, for their citizens in the pre- historic period of this region. -

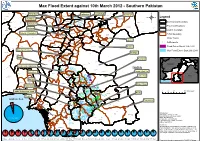

Max Flood Extent Against 10Th March 2012

Max Flood Extent against 10th March 2012 - Southern Pakistan R R R R R R Nuttal Shahpur Derawar Fort Sanni Bhag R Rajhan Shaikh Salar Bhag R R Kalat Chattar R Garhi Ikhtiar Khan Mamatawa R Nasirabad Gandava R Asreli Chauki Jacobabad Gandawa R SuiJaffarabad R Sui Shori Data Kashmore R De- Excluded Area Rajanpur Rojhan Khanpur (Rahim Yar Khan) Kharan Zehri Dera murad jamali Shahwali R Surab Sohbatpur R Tamboo Rahim Yar Khan Legend Garruk Kashmore R JhalGazan Magsi Abad R Rahim Yar Khan R R R Khan Baba kot R R Jhatpat Jhat Pat R Khangarh Toba Anjira R R R Jaccobabad Kashmore R Nawa Kot Surab Jhal Magsi Yazman . International boundary R Jacobabad Thul R R Sadiqabad Sadiqabad R Khanpur R Kandhkot ShikarpurR Kandi Thul Tangwani Jacobabad Mirpur Jhal Magsi Jaffarabad R R R Ubauro Usta Muhammad R Ghauspur Ubauro Provincial boundary Alat Hatachi Liaquatpur R R Bijnot Kanhdkot R Gandakha R Garhi Khairo Shikarpur Larkana Khanpur (Shikarpur) R Mirpur Mathelo Garhi Khairo Ghotki Besima Shikarpur District boundary R Shahdadkot Kakiwala Toba Pariko Garhi Yasin R R Tebri R Sandh R R Pano Aqil Khanpur Islamgarh Khuzdar Shahdadkot Garhi Yasin Lakhi R Qambar Shadadkot R Pano Aqil R R Shireza Qubo Saeed Khan Raiodero R R Khuzdar R Daharki Tehsil boundary R Karkh Miro Khan Mirpur Mathelo Sukkur Dabar Wahan Sukkur Zidi R Nai R R Rohri R R Ratodero R Major Towns Sangrar Ghaibi Dero R Qambar Shahdad Kot Kingri R Nandewaro Kambar Ali Khan R Rohri R Larkana Ghotki R Khairpur Larkana R !( Khairpur R Mithrau Settlements Gambat Khangarh Mamro Warah Nasirabad R Haji -

06Th ) MONTHLY REVIEW MEETING of DISTRICT HYDERABAD

MINUTES OF THE (06th ) MONTHLY REVIEW MEETING OF DISTRICT HYDERABAD Monthly Review Meeting (M.R.M) of District, Hyderabad for the Month of April, 2012 was held on 15.05.2012 at meeting Hall of Ex-Zila Nazim Office, Hyderabad. ritten invitations to participate were sent to the Administrator/ DCO, the D.H.O, all Focal persons of Vertical Programs, District Population Officer i.e EPI, TB DOTS,MNCH, National Program, Malaria Control, Hepatitis, DHIS & DEWS, representatives WHO, all I/c Medical Officers/ FMOs/LHVs etc. List of Participants: Sr. Names Designation S # Names Designation 1. Agha Shahnawaz Babar D.C Hyderabad 45 Dr. Aruna Kumari FMO 2. Abid Salemm A.D. C, Hyd. 46 Dr. Aqsa Mushtaque FMO 3. Abdul Shakoor Shaikh DSM, PPHI 47 Dr. Rubina Abro FMO 4. Dr. Altaf Khero Act: DHO 48 Dr. Jahan Ara FMO 5. Dr. Iqtedar Hussain DTC Hyd 49 Dr. Naila Sheikh FMO 6. Dr. Qazi Rasheed Ahmed F.P, DHIS 50 Dr. Sadia Pir FMO 7. Mr. Athar Ali Memon Ex: M&E 51 Dr. Rukhsana Dal Sonologist 8. Maqsood Ahmed SO 52 Dr. Farzana Chachar Sonologist 9. Dr. Rafique Ahmed SMO 53 Dr. Shazia Zeeshan FMO 10. Dr. Muhammad Ali MO 54 Dr. Anaila Soomro WMO 11. Dr. Ammnullah Shahani SMO 55 Dr. Rahila Solangi WMO MNCH 12. Dr. Capt: Nasarullah SMO (MS) 56 Dr. Mumtaz Rajper FMO 13. Dr. Azeem Shah SMO I/C 57 Dr. Neelofer Kazi FMO 14. Dr. A. Majeed Samoon SMO I/C 58 Dr. Rubina Sheikh SWMO 15. Dr. Raza Muhammad SMO I/C 59 Dr. -

IHH Mir Husain Ali Khan, Son of Mir Nur Muhammad

ApPENDIX I. LIST OF PRIVILEGED AND OTHER PERSONS OF THE TALPUR FAMILY RESIDING IN THE PROVINCE or SIND. Age in Name. PIa,e oC Residence. To what estent Educated. How Employed. -1814. I I. H.H. MIr Husain Ali Khan, son of Mir 49 Hyderabad Is acquainted with Persian Not in any employment. Nur Muhammad Khan (deceased). and Arabic. 2. H.H. Mir Hasan Ali Khan, son of the ex· 44 Ditto. Ditto. , Ditto. Mir Nasir Khan (deceased), 3. H.lL Mir Sher Muhammad Khan, C.S. I., 65 Ditto. Ditto •. Ditto. ex.Mir of Mirpur, son of Mir Ali Murad Khan (deceased). 4- H.H. Mir Shah Nawaz Khan, son of ex· 26 Ditto. Ditto. Ditto. Mir Nur Muhammad Khan (deceased), S. lLH. Abdul Husain Khan, son of Mir 18 Ditto. , . In addition to the above, Ditto• Abbas Ali Khan (deceased). has a slight knowledge of English. 6. H.H. Mir Khan Muhammad Khan, son 46 Alahyar·jo-Tando Is versed in Persian and Ditto. of Mir Ali Murad of Mirpur (deceased). Arabic. 7. Mir Ali Mardan Khan, son of H.H. Mir 62 Mirpur Khas . Ditto, , Ditto. Rustam Khan (deceased). 00 I ~... IAge in Place of Residence. To what extent Educated. How Employed. Name. 1874. t 8. Mir Fateh Khan, son of H.H. Mir Sher 39 Mirpur Khas Fairly in Persian Not in any employment. Muhammad Khin. 9. ·Mir Ghulam Muhammad Khan, son of SI Ditto. Ditto. Ditto. H.H. Mir Rustam Khan (deceased). 10: Mir Imam Bakhsh Khan, son of H.H. 26 Ditto. Ditto. Ditto. -

Sindh Solar Energy Project

Sindh Solar Energy Project Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework Public Disclosure Authorized February 2018 Public Disclosure Authorized ESMF for Sindh Solar Energy Project Contents List of Acronyms ............................................................................................................ 1-1 Glossary of Terms .......................................................................................................... 1-4 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... 1-7 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1-14 1.1. Project Overview ........................................................................................... 1-14 1.2. Legal and Policy Frameworks relevant to Environmental and Social Aspects . 1- 15 1.3. Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF)....................... 1-15 1.4. ESMF Methodology....................................................................................... 1-16 1.4.1. Review of the Project Details ........................................................... 1-16 1.4.2. Review of Relevant Legislation, Policies, and Guidelines .............. 1-17 1.4.3. Review of Secondary Literature ....................................................... 1-17 1.4.4. Scoping ............................................................................................