A Sunday's Journey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools JUL 0 2 2003

Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools By Mahjabeen Quadri B.S. Architecture Studies University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2001 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2003 JUL 0 2 2003 Copyright@ 2003 Mahjabeen Quadri. Al rights reserved LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: Mahjabeen Quadri Departm 4t of Architecture, May 19, 2003 Certified by:- Reinhard K. Goethert Principal Research Associate in Architecture Department of Architecture Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Julian Beinart Departme of Architecture Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students ROTCH Thesis Committee Reinhard Goethert Principal Research Associate in Architecture Department of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Edith Ackermann Visiting Professor Department of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Anna Hardman Visiting Lecturer in International Development Planning Department of Urban Studies and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Hashim Sarkis Professor of Architecture Aga Khan Professor of Landscape Architecture and Urbanism Harvard University Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools By Mahjabeen Quadri Submitted to the Department of Architecture On May 23, 2003 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies Abstract Pakistan's greatest resource is its children, but only a small percentage of them make it through primary school. -

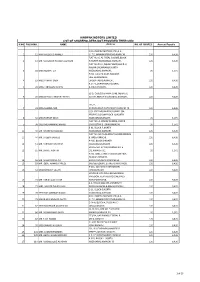

Hinopak Motors Limited List of Shareholders Not Provided Their Cnic S.No Folio No

HINOPAK MOTORS LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS NOT PROVIDED THEIR CNIC S.NO FOLIO NO. NAME Address NO. OF SHARES Amount Payable C/O HINOPAK MOTORS LTD.,D-2, 1 12 MIR MAQSOOD AHMED S.I.T.E.,MANGHOPIR ROAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO. 6, AL-FAZAL SQUARE,BLOCK- 2 13 MR. MANZOOR HUSSAIN QURESHI H,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 FLAT NO.19-O, IQBAL PLAZA,BLOCK-O, NAGAN CHOWRANGI,NORTH 3 18 MISS NUSRAT ZIA NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 20 1,071 H.NO. E-13/40,NEAR RAILWAY LINE,GHARIBABAD, 4 19 MISS FARHAT SABA LIAQUATABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 R.177-1,SHARIFABADFEDERAL 5 24 MISS TABASSUM NISHAT B.AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 52-D, Q-BLOCK,PAHAR GANJ, NEAR LAL 6 28 MISS SHAKILA ANWAR FATIMA KOTTHI,NORTH NAZIMABAD,KARACHI., 120 6,426 171/2, 7 31 MISS SAMINA NAZ AURANGABAD,NAZIMABAD,KARACHI-18. 120 6,426 C/O. SYED MUJAHID HUSSAINP-394, PEOPLES COLONYBLOCK-N, NORTH 8 32 MISS FARHAT ABIDI NAZIMABADKARACHI, 20 1,071 FLAT NO. A-3FARAZ AVENUE, BLOCK- 9 38 SYED MOHAMMAD HAMID 20GULISTAN-E-JOHARKARACHI, 20 1,071 B-91, BLOCK-P,NORTH 10 40 MR. KHURSHID MAJEED NAZIMABAD,KARACHI. 120 6,426 FLAT NO. M-45,AL-AZAM SQUARE,FEDRAL 11 44 MR. SALEEM JAWEED B. AREA,KARACHI., 120 6,426 A-485, BLOCK-DNORTH 12 51 MR. FARRUKH GHAFFAR NAZIMABADKARACHI. 120 6,426 HOUSE NO. D/401,KORANGI NO. 5 13 55 MR. SHAKIL AKHTAR 1/2,KARACHI-31. 20 1,071 H.NO. 3281, STREET NO.10,NEW FIDA HUSSAIN SHAIKHA 14 56 MR. -

Muslim Saints of South Asia

MUSLIM SAINTS OF SOUTH ASIA This book studies the veneration practices and rituals of the Muslim saints. It outlines the principle trends of the main Sufi orders in India, the profiles and teachings of the famous and less well-known saints, and the development of pilgrimage to their tombs in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. A detailed discussion of the interaction of the Hindu mystic tradition and Sufism shows the polarity between the rigidity of the orthodox and the flexibility of the popular Islam in South Asia. Treating the cult of saints as a universal and all pervading phenomenon embracing the life of the region in all its aspects, the analysis includes politics, social and family life, interpersonal relations, gender problems and national psyche. The author uses a multidimen- sional approach to the subject: a historical, religious and literary analysis of sources is combined with an anthropological study of the rites and rituals of the veneration of the shrines and the description of the architecture of the tombs. Anna Suvorova is Head of Department of Asian Literatures at the Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow. A recognized scholar in the field of Indo-Islamic culture and liter- ature, she frequently lectures at universities all over the world. She is the author of several books in Russian and English including The Poetics of Urdu Dastaan; The Sources of the New Indian Drama; The Quest for Theatre: the twentieth century drama in India and Pakistan; Nostalgia for Lucknow and Masnawi: a study of Urdu romance. She has also translated several books on pre-modern Urdu prose into Russian. -

(Nip) for Phasing out and Elimination of Pops From

Government of Pakistan Ministry of Environment Islamabad NATIONAL IMPLEMENTATION PLAN (NIP) FOR PHASING OUT AND ELIMINATION OF POPS FROM PAKISTAN UNDER STOCKHOLM CONVENTION ARTICLE 7 (a) POPs, Enabling Activity Project, Islamabad, PAKISTAN. Page 1 of 842 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................... ..2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................................... 3 ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................... 17 1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................... 20 Objectives of the National Implementation Plan (NIP) ........................................................ 21 2. COUNTRY BASELINE .................................................................................................. 23 2.1. Country Profile .............................................................................................................. 23 2.1.1. Location, Geography and Climate.......................................................................... 23 2.1.2 Population, education, health and employment ....................................................... 27 2.1.3 Overview of the economy........................................................................................ 30 2.1.4 Economic sectors.................................................................................................... -

The Land of Five Rivers and Sindh by David Ross

THE LAND OFOFOF THE FIVE RIVERS AND SINDH. BY DAVID ROSS, C.I.E., F.R.G.S. London 1883 Reproduced by: Sani Hussain Panhwar The land of the five rivers and Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 TO HIS EXCELLENCY THE MOST HONORABLE GEORGE FREDERICK SAMUEL MARQUIS OF RIPON, K.G., P.C., G.M.S.I., G.M.I.E., VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, THESE SKETCHES OF THE PUNJAB AND SINDH ARE With His Excellency’s Most Gracious Permission DEDICATED. The land of the five rivers and Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 PREFACE. My object in publishing these “Sketches” is to furnish travelers passing through Sindh and the Punjab with a short historical and descriptive account of the country and places of interest between Karachi, Multan, Lahore, Peshawar, and Delhi. I mainly confine my remarks to the more prominent cities and towns adjoining the railway system. Objects of antiquarian interest and the principal arts and manufactures in the different localities are briefly noticed. I have alluded to the independent adjoining States, and I have added outlines of the routes to Kashmir, the various hill sanitaria, and of the marches which may be made in the interior of the Western Himalayas. In order to give a distinct and definite idea as to the situation of the different localities mentioned, their position with reference to the various railway stations is given as far as possible. The names of the railway stations and principal places described head each article or paragraph, and in the margin are shown the minor places or objects of interest in the vicinity. -

December 2013 405 Al Baraka Bank (Pakistan) Ltd

Appendix IV Scheduled Banks’ Islamic Banking Branches in Pakistan As on 31st December 2013 Al Baraka Bank -Lakhani Centre, I.I.Chundrigar Road Vehari -Nishat Lane No.4, Phase-VI, D.H.A. (Pakistan) Ltd. (108) -Phase-II, D.H.A. -Provincial Trade Centre, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Askari Bank Ltd. (38) Main University Road Abbottabad -S.I.T.E. Area, Abbottabad Arifwala Chillas Attock Khanewal Faisalabad Badin Gujranwala Bahawalnagar Lahore (16) Hyderabad Bahawalpur -Bank Square Market, Model Town Islamabad Burewala -Block Y, Phase-III, L.C.C.H.S Taxila D.G.Khan -M.M. Alam Road, Gulberg-III, D.I.Khan -Main Boulevard, Allama Iqbal Town Gujrat (2) Daska -Mcleod Road -Opposite UBL, Bhimber Road Fateh Jang -Phase-II, Commercial Area, D.H.A. -Near Municipal Model School, Circular Gojra -Race Course Road, Shadman, Road Jehlum -Block R-1, Johar Town Karachi (8) Kasur -Cavalry Ground -Abdullah Haroon Road Khanpur -Circular Road -Qazi Usman Road, near Lal Masjid Kotri -Civic Centre, Barkat Market, New -Block-L, North Nazimabad Minngora Garden Town -Estate Avenue, S.I.T.E. Okara -Faisal Town -Jami Commercial, Phase-VII Sheikhupura -Hali Road, Gulberg-II -Mehran Hights, KDA Scheme-V -Kabeer Street, Urdu Bazar -CP & Barar Cooperative Housing Faisalabad (2) -Phase-III, D.H.A. Society, Dhoraji -Chiniot Bazar, near Clock Tower -Shadman Colony 1, -KDA Scheme No. 24, Gulshan-e-Iqbal -Faisal Lane, Civil Line Larkana Kohat Jhang Mansehra Lahore (7) Mardan -Faisal Town, Peco Road Gujranwala (2) Mirpur (AK) -M.A. Johar Town, -Anwar Industrial Complex, G.T Road Mirpurkhas -Block Y, Phase-III, D.H.A. -

Beliefs and Behaviors of Shrine Visitors of Bibi Pak Daman

Journal of Gender and Social Issues Spring 2020, Vol. 19, Number 1 ©Fatima Jinnah Women University, Rawalpindi Beliefs and Behaviors of Shrine Visitors of Bibi Pak Daman Abstract The present study aims at focusing on what kind of beliefs are associated with the shrine visits that make them visitors believe and behave in a specific way. The shrine selected for this purpose was Bibi Pak Daman, Lahore, Pakistan. The visitors of this shrine were observed using non- participant observation method. Field notes were used to record observations and the data were analyzed using thematic analysis. Three major themes emerged out of the data. The first major theme of immortality appeared with sub-themes of belief in existence after death, belief in supernatural powers of chaste ladies and objects placed at the shrine. The second theme that emerged consisted of superstitions with the sub-themes of superstitions related to objects and miracles/mannat system. The third theme that emerged was of the beliefs in the light of the placebo effect and the sub-themes included prayer fulfillment, enhanced spirituality and problem resolution. Keywords: Bibi Pak Daman, beliefs, shrine visitors INTRODUCTION Islam has a unique role in meeting the spiritual needs of its followers through Sufism, which is defined as a system of beliefs wherein Muslims search for their spiritual knowledge in the course of direct personal experience and practice of Allah Almighty (Khan & Sajid, 2011). Sufism represents the spiritual dimension of Islam. Sufis played a major role in spreading Islam throughout the sub-continent, sometimes even more than the warriors. In early 12th century, Sufi saints connected the Hindus and Muslims with their deep devotion and love for God as the basic tenet of belief. -

Kurrachee (Karachi) Past: Present and Future

KURRACHEE (KARACHI) PAST: PRESENT AND FUTURE ALEXANDER F. BAILLIE, F.R.G.S., 1880 BIRD'S EYE VIEW OF VICTORIA ROAD CLERK STREET, SADDAR BAZAR KARACHI REPRODUCED BY SANI H. PANHWAR (2019) KUR R A CH EE: PA ST:PRESENT:A ND FUTURE. KUR R A CH EE: (KA R A CH I) PA ST:PRESENT:A ND FUTURE. BY A LEXA NDER F.B A ILLIE,F.R.G.S., A uthor of"A PA RA GUA YA N TREA SURE,"etc. W ith M a ps,Pla ns & Photogra phs 1890. Reproduced by Sa niH .Panhw a r (2019) TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE SIR MOUNTSTUART ELPHINSTONE GRANT-DUFF, P.C., G.C.S.I., C.I.E., F.R.S., M.R.A.S., PRESIDENT OF THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY, FORMERLY UNDER-SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INDIA, AND GOVERNOR OF THE PROVINCE OF MADRAS, ETC., ETC., THIS ACCOUNT OF KURRACHEE: PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE, IS MOST RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY HIS OBEDIENT SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. INTRODUCTION. THE main objects that I have had in view in publishing a Treatise on Kurrachee are, in the first place, to submit to the Public a succinct collection of facts relating to that City and Port which, at a future period, it might be difficult to retrieve from the records of the Past ; and secondly, to advocate the construction of a Railway system connecting the GateofCentralAsiaand the Valley of the Indus, with the Native Capital of India. I have elsewhere mentioned the authorities to whom I am indebted, and have gratefully acknowledged the valuable assistance that, from numerous sources, has been afforded to me in the compilation of this Work; but an apology is due to my Readers for the comments and discursions that have been interpolated, and which I find, on revisal, occupy a considerable number of the following pages. -

373 Part 744—Control Policy

Bureau of Industry and Security, Commerce Pt. 744 GOV (§ 740.11(b) of the EAR) do not re- Turkey United Kingdom quire such notification. Ukraine United States (2) Exports of ‘‘600 Series Major De- [63 FR 55020, Oct. 14, 1998, as amended at 70 fense Equipment’’ that have been or FR 41102, July 15, 2005; 71 FR 52964; Sept. 7, will be described in a notification filed 2006; 77 FR 39369, July 2, 2012] by the U.S. State Department under the Arms Export Control Act do not re- PART 744—CONTROL POLICY: END- quire such notification by BIS. USER AND END-USE BASED (b) BIS will notify Congress prior to issuing a license authorizing the export Sec. of items to a country outside the coun- 744.1 General provisions. tries listed in Country Group A:5 (see 744.2 Restrictions on certain nuclear end- uses. supplement no. 1 to part 740 of the 744.3 Restrictions on certain rocket systems EAR) that are sold under a contract (including ballistic missiles, space that includes $14,000,000 or more of ‘‘600 launch vehicles and sounding rockets) Series Major Defense Equipment.’’ and unmanned aerial vehicles (including (c) BIS will notify Congress prior to cruise missiles, target drones and recon- issuing a license authorizing the export naissance drones) end-uses. 744.4 Restrictions on certain chemical and of items to a country listed in Country biological weapons end-uses. Group A:5 (see supplement no. 1 to part 744.5 Restrictions on certain maritime nu- 740 of the EAR) that are sold under a clear propulsion end-uses. -

List of Merchants Issuing Cards

Merchant/Agent Name MID/AID Merchant Address Merchant Mobile No Merchant/Agent Region Assigned credit limit Avaiable Credit Limit Re-ordering Qty EQQ Merchant/Agent Status Total 0.1% Commission TotalCardsReceivedToDate TotalCardsIssuedToCustomer TotalCardsInHand PriceChargedReorderedQuantity Total Cards Refund DeviceUsed PSO SERVICE STATION 3 (M.G MOTORS) 000001670015541 NEAR PSO HOUSE, KHAYABAN-E-IQBAL, CLIFTON KARACHI 03452335649 KARACHI 1000000 782524 120 300 Active 189257.31 5290 4995 295 5000 0 Yes AMBER SERVICE STATION 000001340015541 B-6, SITE AREA, MANGHOPIR ROAD KARACHI KARACHI 500000 475000 10 25 Active 6022.38 225 167 58 5000 0 Yes MACCA MOBILE SERVICE 000001550015541 1036, JAIL CHOWANGI, M.A. JINNAH ROAD KARACHI KARACHI 500000 500000 40 100 Active 15317.26 430 375 55 30000 0 Yes PSO SERVICE STATION 25 (ITTEHAD) 000001400015541 KHAYABAN-E-ITTEHAD, DEFENCE PHASE V KARACHI KARACHI 1000000 760610 100 250 Active 78415.63 3475 3262 213 5000 0 Yes STADIUM SERVICE STATION 000001770015541 ADJACENT AGHA KHAN HOSPITAL, STADIUM ROAD KARACHI KARACHI 500000 461700 100 250 Active 53302.66 1725 1388 212 5000 125 Yes AL-MADINA SERVICE STATION 000001320015541 ST-2 BLOCK-4 SECTOR-5C, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI 400000 400000 40 100 Active 8239.65 400 286 114 20000 0 Yes AL-YASIN FILLING STATION 000001330015541 PLOT NO. ST-1/2 BLOCK NO. 1, 15/A-1 , NORTH KARACHI KARACHI 300000 497157 20 30 Active 3163.58 50 29 21 4000 0 Yes ARABIAN GASOLINE 000001360015541 ST 1/9, SECTOR 15, KORANGI INDUSTRIAL AREA KARACHI 500000 480000 40 100 Active 11333.46 400 283 117 20000 0 Yes CHOWRANGI SERVICE STATION 000001390015541 1ST CHOWRANGI, NAZIMABAD KARACHI KARACHI 500000 494470 20 30 Active 3306.29 200 120 80 30000 0 Yes MIDWAY PETROLEUM SERVICES 000041440035541 MAIN DOUBLE ROAD H-11/1, ISLAMABAD ISLAMABAD 300000 233080 40 100 Active 17440.24 700 477 131 20000 92 Yes P S O SERVICE STATION 7 (A. -

Informal Land Controls, a Case of Karachi-Pakistan

Informal Land Controls, A Case of Karachi-Pakistan. This Thesis is Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Saeed Ud Din Ahmed School of Geography and Planning, Cardiff University June 2016 DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… i | P a g e STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of …………………………(insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed ………………………………………………………………………..………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed …………………………………………………………….…………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ……………………………………………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed …………………………………………………….……………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… ii | P a g e iii | P a g e Acknowledgement The fruition of this thesis, theoretically a solitary contribution, is indebted to many individuals and institutions for their kind contributions, guidance and support. NED University of Engineering and Technology, my alma mater and employer, for financing this study. -

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES and MONUMENTS in SINDH PROVINCE PROTECTED by the FEDERAL GOVERNMENT Badin District 1

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES AND MONUMENTS IN SINDH PROVINCE PROTECTED BY THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT Badin District 1. Runs of old city at Badin, Badin Dadu District 2. Tomb of Yar Muhammad Khan kalhora and its adjoining Masjid near khudabad, Dadu. 3. Jami Masjid, Khudabad, Dadu. 4. Rani Fort Kot, Dadu. 5. Amri, Mounds, Dadu. 6. Lakhomir-ji-Mari, Deh Nang opposite Police outpost, Sehwan, Dadu. 7. Damb Buthi, Deh Narpirar at the source of the pirari (spring), south of Jhangara, Sehwan, Dadu. 8. Piyaroli Mari, Deh Shouk near pir Gaji Shah, Johi, Dadu. 9. Ali Murad village mounds, Deh Bahlil Shah, Johi, Dadu. 10. Nasumji Buthi, Deh Karchat Mahal, Kohistan, Dadu. 11. Kohtrass Buthi, Deh Karchat about 8 miles south-west of village of Karchat on road from Thana Bula Khan to Taung, Dadu. 12. Othamjo Buthi Deh Karchat or river Baran on the way from the Arabjo Thano to Wahi village north-west of Bachani sandhi, Mahal, Kohistan, Dadu. 13. Lohamjodaro, Deh Palha at a distance of 30 chains from Railway Station but not within railway limits, Dadu. 14. Pandhi Wahi village mounds, Deh Wahi, Johi, Dadu. 15. Sehwan Fort, Sehwan, Dadu. 16. Ancient Mound, Deh Wahi Pandhi, Johi, Dadu. 17. Ancient Mound, Deh Wahi Pandhi, Johi, Dadu. Hyderabad District 18. Tomb of Ghulam Shah Kalhora, Hyderabad. 19. Boundary Wall of Pucca Fort, Hyderabad. 20. Old office of Mirs, Hyderabad Fort, Hyderabad. 21. Tajar (Treasury) of Mirs, Hyderabad Fort, Hyderabad. 22. Tomb of Ghulam Nabi Khan Kalhora, Hyderabad. 23. Buddhist Stupa, (Guja) a few miles from Tando Muhammad Khan, Hyderabad. 24.