“The Portrait Recovered” (“Shihua” ਕ), of Tang Xian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

From Story to Script: Towards a Morphology of the Peony Pavilion–– a Dream/ Ghost Drama from Ming China

From Story to Script: towards a Morphology of The Peony Pavilion–– a Dream/ Ghost Drama from Ming China Xiaohuan Zhao University of Otago, Donghua University This article is an attempt to analyze the dramatic structure of the Mudan ting 牡丹 亭 (Peony Pavilion) as a piece of fantasy which Tang Xianzu 湯顯祖 (1550–1616) created through the utilisation of structural devices and techniques of magic tales. The particular model adopted for the textual analysis is that formulated by Vladimir Propp in Morphology of Russian Folktale. This paper starts with a comparison of Russian magic tales Propp investigated for his morphological study and Chinese zhiguai 志怪 tales which provide the prototype for the Mudan ting with a view of justifying the application of the Proppian model. The second part of this paper is devoted to a critical review of the Proppian model and method in terms of function versus non-function, tale versus move, and character versus tale / theatrical role. Further information is also given in this part as a response to challenges and criticisms this article may incur as regards the applicability of the Proppian model in inter-cultural and inter-generic studies. Part Three is a morphological analysis of the dramatic text with a focus on the main storyline revolving around the hero and heroine. In the course of textual analysis, the particular form and sequence of functions is identified, the functional scheme of each move presented, and the distribution of dramatis personae in accordance with the sphere(s) of action of characters delineated. Finally this paper concludes with a presentation of the overall dramatic structure and strategy of this play. -

Stories to Caution the World: a Ming Dinasty Collection (Volume 2)

Stories to Caution the World μ@q• Stories to Caution the World a ming dynasty collection volume 2 Compiled by Feng Menglong (1574–1646) Translated by Shuhui Yang and Yunqin Yang university of washington press seattle and london Publication of Stories to Caution the World has been generously supported by Bates College. © 2005 by the University of Washington Press Printed in the United States of America 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. University of Washington Press P.O. Box 50096, Seattle, WA 98145 www.washington.edu/uwpress Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Feng, Menglong, 1574–1646. [Jing shi tong yan. English] Stories to caution the world : a Ming dynasty collection / compiled by Feng Menglong ; translated by Shuhui Yang and Yunqin Yang. p. cm. isbn 0-295-98552-6 (hardback : alk. paper) I. Yang, Shuhui. II. Yang, Yunqin. III. Title. pl2698.f4j5613 2005 895.1'346—dc22 2005010013 The paper used in this publication is acid-free and 90 percent recycled from at least 50 percent post-consumer waste. It meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984. To our parents and sisters Contents Acknowledgments xi Introduction xiii Translators’ Note xvii Chronology of Chinese Dynasties xix stories to caution the world Title Page from the 1624 Edition 3 Preface to the 1624 Edition 5 1. -

Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies in Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 In The Eye Of The Selector: Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies In Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China Timothy Robert Clifford University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Clifford, Timothy Robert, "In The Eye Of The Selector: Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies In Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2234. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2234 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2234 For more information, please contact [email protected]. In The Eye Of The Selector: Ancient-Style Prose Anthologies In Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) China Abstract The rapid growth of woodblock printing in sixteenth-century China not only transformed wenzhang (“literature”) as a category of knowledge, it also transformed the communities in which knowledge of wenzhang circulated. Twentieth-century scholarship described this event as an expansion of the non-elite reading public coinciding with the ascent of vernacular fiction and performance literature over stagnant classical forms. Because this narrative was designed to serve as a native genealogy for the New Literature Movement, it overlooked the crucial role of guwen (“ancient-style prose,” a term which denoted the everyday style of classical prose used in both preparing for the civil service examinations as well as the social exchange of letters, gravestone inscriptions, and other occasional prose forms among the literati) in early modern literary culture. This dissertation revises that narrative by showing how a diverse range of social actors used anthologies of ancient-style prose to build new forms of literary knowledge and shape new literary publics. -

SHAKESPEARE STUDIES in CHINA by Hui Meng Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the Un

SHAKESPEARE STUDIES IN CHINA By Copyright 2012 Hui Meng Submitted to the graduate degree program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Geraldo U. de Sousa ________________________________ Misty Schieberle ________________________________ Jonathan Lamb Date Defended: April 3, 2012 ii The Thesis Committee for Hui Meng certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: SHAKESPEARE STUDIES IN CHINA ________________________________ Chairperson Geraldo U. de Sousa Date approved: April 3, 2012 iii Abstract: Different from Germany, Japan and India, China has its own unique relation with Shakespeare. Since Shakespeare’s works were first introduced into China in 1904, Shakespeare in China has witnessed several phases of developments. In each phase, the characteristic of Shakespeare studies in China is closely associated with the political and cultural situation of the time. This thesis chronicles and analyzes noteworthy scholarship of Shakespeare studies in China, especially since the 1990s, in terms of translation, literary criticism, and performances, and forecasts new territory for future studies of Shakespeare in China. iv Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………1 Section 1 Oriental and Localized Shakespeare: Translation of Shakespeare’s Plays in China …………………………………………………………………... 3 Section 2 Interpretation and Decoding: Contemporary Chinese Shakespeare Criticism………………………………………………………………. -

Women, Autonomy, and Desire in Feng Menglong's Short Stories

Women, Autonomy, and Desire in Feng Menglong’s Short Stories Rosa Hargrove Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in Chinese Language & Culture April 2015 Hargrove 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………...2 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………...3 Chapter 1: The Limits of Virtue………………………………………………………10 Chapter 2: Heavenly Retribution……………………………………………………...32 Chapter 3: Retribution and Balance…………………………………………………..48 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….67 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………..73 Hargrove 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Sarah Allen for all of her patience and guidance throughout this process. Being her student was one of the most enriching parts of my experience at Wellesley, and I am extremely grateful for all of her help in this project. I would also like to thank the EALC faculty for their support and my thesis committee for their willingness to read and comment on my work. I’m also indebted to Charlotte, Delia, Judy, Narayani, Neha, and everyone else in my Wellesley family for reminding me to laugh, stay hydrated, and believe in myself. I would also like to thank my longsuffering parents, grandparents, and friends from home for being so patient about not having their phone calls returned for the past few months. Hargrove 3 Introduction Feng Menglong’s (15741645) collection of stories constitute some of the most important works in Chinese fiction. The Ming Dynasty author and lateblooming scholar recorded a total of 120 stories, forty in each of three volumes, referred to as the Sanyan (literally “three words”). The three works’ individual titles are Stories Old and New, Stories to Caution the World, and Stories to Awaken the World. -

Kunqu Opera in the Last Hundred Years in China

Review of Educational Theory | Volume 02 | Issue 04 | October 2019 Review of Educational Theory https://ojs.bilpublishing.com/index.php/ret REVIEW Kunqu Opera in the Last Hundred Years in China Yue Wang* The University of Milan, Milan, 20122, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history Kunqu, literally means kun melody, is one of the most ancient forms of Received: 26 September 2019 Chinese opera. Originally her melody derives from Kunshan zone of Jiangsu province therefore it has been named Kunshan melody before, Revised: 15 October 2019 now Kunqu also known as Kunju, which means Kunqu opera. This paper Accepted: 21 October 2019 mainly focuses on the development of Kunqu in the past 100 years and the Published Online: 31 October 2019 influence of historical social and humanistic changes behind the special era on Kunqu, and compares the attitudes of scholars of different schools Keywords: of thought in different eras to Kunqu and the social public to compare and analyze the degree of love of Kunqu. Kunqu Last hundred years Development Inuence 1. Introduction opera have been developed on the basis of Kunqu. It is the most complete type of drama in the history of Chinese The original name of Kunqu is “tune of KunShan”, is opera, the biggest feature is the lyrical and delicate move- the ancient Chinese opera intonation type of drama, now ments, the combination of singing and dancing is inge- known as the “Kun drama”. Originated from the Yuan nious and harmonious ,in the costumes and make-up, the Dynasty (the middle of the 14th century), it’s a traditional generals have various kinds of costumes, the civil servants Chinese culture and art of the Han ethnic group. -

Representing Talented Women in Eighteenth-Century Chinese Painting: Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instruction at the Lake Pavilion

REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION By Copyright 2016 Janet C. Chen Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler ________________________________ Amy McNair ________________________________ Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Jungsil Jenny Lee ________________________________ Keith McMahon Date Defended: May 13, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Janet C. Chen certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler Date approved: May 13, 2016 ii Abstract As the first comprehensive art-historical study of the Qing poet Yuan Mei (1716–97) and the female intellectuals in his circle, this dissertation examines the depictions of these women in an eighteenth-century handscroll, Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instructions at the Lake Pavilion, related paintings, and the accompanying inscriptions. Created when an increasing number of women turned to the scholarly arts, in particular painting and poetry, these paintings documented the more receptive attitude of literati toward talented women and their support in the social and artistic lives of female intellectuals. These pictures show the women cultivating themselves through literati activities and poetic meditation in nature or gardens, common tropes in portraits of male scholars. The predominantly male patrons, painters, and colophon authors all took part in the formation of the women’s public identities as poets and artists; the first two determined the visual representations, and the third, through writings, confirmed and elaborated on the designated identities. -

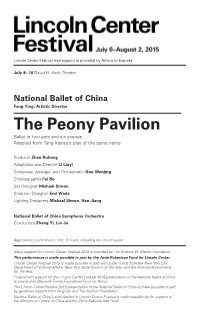

National Ballet of China Feng Ying, Artistic Director the Peony Pavilion Ballet in Two Acts and Six Scenes Adapted from Tang Xianzu’S Play of the Same Name

07-08 Peony_Gp 3.qxt 6/29/15 2:42 PM Page 1 Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 8 – 10 David H. Koch Theater National Ballet of China Feng Ying, Artistic Director The Peony Pavilion Ballet in two acts and six scenes Adapted from Tang Xianzu’s play of the same name Producer Zhao Ruheng Adaptation and Director Li Liuyi Composer, Arranger, and Orchestrator Guo Wenjing Choreographer Fei Bo Set Designer Michael Simon Costume Designer Emi Wada Lighting Designers Michael Simon, Han Jiang National Ballet of China Symphony Orchestra Conductors Zhang Yi, Liu Ju Approximate performance time: 2 hours, including one intermission Major support for Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Lincoln Center Festival 2015 is made possible in part with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, New York State Council on the Arts, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Endowment support for the Lincoln Center Festival 2015 presentation of the National Ballet of China is provided by Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance. The Lincoln Center Festival 2015 presentation of the National Ballet of China is made possible in part by generous support from Yang Lan and The Joelson Foundation. National Ballet of China’s participation in Lincoln Center Festival is made possible by the support of the Ministry of Culture of China and the China National Arts Fund. 07-08 Peony_Gp 3.qxt 6/29/15 2:42 PM Page 2 LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2015 THE PEONY PAVILION July 8, 2015, at 8:00 p.m. -

Women and Men, Love and Power: Parameters of Chinese Fiction and Drama

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 193 November, 2009 Women and Men, Love and Power: Parameters of Chinese Fiction and Drama edited and with a foreword by Victor H. Mair Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series edited by Victor H. Mair. The purpose of the series is to make available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including Romanized Modern Standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino-Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. The only style-sheet we honor is that of consistency. Where possible, we prefer the usages of the Journal of Asian Studies. Sinographs (hanzi, also called tetragraphs [fangkuaizi]) and other unusual symbols should be kept to an absolute minimum. -

The Social Setting of Chinese Religious

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 310 March, 2021 The Social Setting of Chinese Religious Storytelling in the Late Sixteenth – Early Seventeenth Centuries: A Passage from the Novel Pacification of the Demons’ Revolt (1620) by Rostislav Berezkin Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino-Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out for peer review, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. -

How I Enjoyed the Peony Pavilion!

FEATURE How I Enjoyed The Peony Pavilion! By Chia-Hui Shih I enjoyed the performance of The Peony Pavilion so much that I wrote of my experiences with the show in two parts: first my overall impression as a layman and then my appreciation of the performance on each of the three days that the show lasted. Part I: A Layman’s Experience On September 22 to 24, I watched The Peony Pavilion at the Barclay Theater in Irvine, Calif. It was presented by a Chinese Kunqu opera company from Suzhou, Jiangsu Province. Tang Xian Zu (the Ming Dynasty, 1550- 1616) wrote the libretti, originally consisting of 55 acts. I have never seen a Kunqu production, nor even heard any recital of Kunqu. My closer encounter with the play came some twenty years The melodies (if they could be called ago when I read a play written by Bai Xian Yong melodies, more like tones) in Kunqu are quite (the producer of The Peony Pavilion) named different from those in the popular Jingju (Peking “Visiting a Garden, Startled in a Dream”. It was Opera), are more monotonous—at least to the based on one episode of The Peony Pavilion. untrained ears of mine. On the other hand, the non-singing parts, such as the movement of eyes, hands, and arms; walking styles of men and women; and the dialogue were quite similar to those in Jingju. Actually I had expected that the spoken lines would be the dialect of Suzhou, but it turned out to be a mixture of Mandarin and some Jiangsu dialects, including that of Suzhou.