Multi-Ethnic Stakeholders and Their Perspective of Culture-Based Intervention Programs in Belize: Case Study of Program for the Garifuna People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estimation of Key Population Size of Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender Women in Belize

Caribbean Vulnerable Communities University of Alabama at Birmingham Estimation of Key Population Size of Men Who Have Sex with Men and Transgender Women in Belize Final Report, October 2018 0 TITLE OF THE PROJECT Estimation of Key Population Size of Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM), and Transgender Women in Belize Final Report, August 1st, 2018 Submitted to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the National AIDES Commission of Belize and the Belize Country Coordinating Mechanism for the Global Fund by the Caribbean Vulnerable Communities Coalition (CVC) and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. PRIMARY INVESTIGATORS AND INSTITUTIONAL AFFILIATIONS Lead Co-Investigators: Henna Budhwani, PhD, MPH, Assistant Professor, Public Health and Deputy Director, Sparkman Center for Global Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham Contact Information: [email protected] or 1 (205) 296-3330 John Waters, MD. MSc, MA (Oxon), Programme Manager, Caribbean Vulnerable Communities Coalition Contact Information: [email protected] or 1 (809) 889-4660 Lead Co-Investigator in Charge of Field Work Julia Hasbun, Lic. Independent Consultant and Field Work Expert Contact information: [email protected] or 1 (809) 421-0362 Research Assistants: Ryan Turley, B.A. M.A. Caribbean Vulnerable Communities Coalition Mugdha Mokashi, University of Alabama at Birmingham Elias Ramos, Lic. Caribbean Vulnerable Communities Coalition W. Lupita Raposo, Caribbean Vulnerable Communities Coalition Expert Demography and Statistics Resource Person Page 1 of 149 University of Alabama at Birmingham K. Ria Hearld, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Health Services Administration, University of Alabama at Birmingham Birmingham, AL 35294 Contact information: [email protected] or 1 (205) 934-1670 Expert Research Resource Person Craig M. -

A Study of the Garifuna of Belize's Toledo District Alexander Gough

Indigenous identity in a contested land: A study of the Garifuna of Belize’s Toledo district Alexander Gough This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 Lancaster University Law School 1 Declaration This thesis has not been submitted in support of an application for another degree at this or any other university. It is the result of my own work and includes nothing that is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated. Many of the ideas in this thesis were the product of discussion with my supervisors. Alexander Gough, Lancaster University 21st September 2018 2 Abstract The past fifty years has seen a significant shift in the recognition of indigenous peoples within international law. Once conceptualised as the antithesis to European identity, which in turn facilitated colonial ambitions, the recognition of indigenous identity and responding to indigenous peoples’ demands is now a well-established norm within the international legal system. Furthermore, the recognition of this identity can lead to benefits, such as a stake in controlling valuable resources. However, gaining tangible indigenous recognition remains inherently complex. A key reason for this complexity is that gaining successful recognition as being indigenous is highly dependent upon specific regional, national and local circumstances. Belize is an example of a State whose colonial and post-colonial geographies continue to collide, most notably in its southernmost Toledo district. Aside from remaining the subject of a continued territorial claim from the Republic of Guatemala, in recent years Toledo has also been the battleground for the globally renowned indigenous Maya land rights case. -

Environmental Statistics for Belize, 2012 Is the Sixth Edition to Be Produced in Belize and Contains Data Set Corresponding to the Year 2010

Environmental Statistics for Belize 2012 Environmental Statistics for Belize 2012 Copyright © 2012 Lands and Surveys Department, Ministry of Natural Resources and Agriculture This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. The Lands and Surveys Department would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this report as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other form of commercial use whatsoever. DISCLAIMER The information contained in this publication is based on information available at the time of the publication and may require updating. Please note that all efforts were made to include reliable and accurate information to eliminate errors, but it is still possible that some inconsistencies remain. We regret for errors or omissions that were unintentionally made. Lands and Surveys Department Ministry of Natural Resources and Agriculture Queen Elizabeth II Blvd. Belmopan, Belize C. A. Phone: 501-802-2598 Fax: 501-802-2333 e-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Printed in Belize, October 2012 [ii] Environmental Statistics for Belize 2012 PREFACE The country of Belize is blessed with natural beauty that ranges from a gamut of biodiversity, healthy forest areas, the largest living coral reef system in the world, ancient heritage and diverse cultures. The global trend of industrialization and development for economic development has not adequately considered the natural environment. As a result, globally our natural resources and environment face tremendous pressures and are at high risk of further disruption. -

“I'm Not a Bloody Pop Star!”

Andy Palacio (in white) and the Garifuna Collective onstage in Dangriga, Belize, last November, and with admirers (below) the voice of thPHOTOGRAPHYe p BYe ZACH oSTOVALLple BY DAVE HERNDON Andy Palacio was more than a world-music star. “I’m not a bloody pop star!” He was a cultural hero who insisted Andy Palacio after an outdoor gig in Hopkins, Belize, that revived the hopes of a was so incendiary, a sudden rainstorm only added sizzle. But if it Caribbean people whose was true that Palacio wasn’t a pop star, you couldn’t tell it from the heritage was slipping away. royal treatment he got everywhere he went last November upon 80 CARIBBEANTRAVELMAG.COM APRIL 2008 81 THE EVENTS OF THAT NOVEMBER TOUR WILL HAVE TO GO DOWN AS PALACIO’S LAST LAP, AND FOR ALL WHO WITNESSED ANY PART OF IT, THE STUFF OF HIS LEGEND. Palacio with his role model, the singer and spirit healer Paul Nabor, at Nabor’s home in Punta Gorda (left). The women of Barranco celebrated with their favorite son on the day he was named a UNESCO Artist for Peace (below left and right). for me as an artist, and for the Belizean people which had not been seen before in those parts. There was no as an audience.” The Minister of Tourism Belizean roots music scene or industry besides what they them- thanked Palacio for putting Belize on the map selves had generated over more than a dozen years of collabora- in Europe, UNESCO named him an Artist tion. To make Watina, they started with traditional themes and for Peace, and the Garifuna celebrated him motifs and added songcraft, contemporary production values as their world champion. -

No. 10232 MULTILATERAL Agreement Establishing The

No. 10232 MULTILATERAL Agreement establishing the Caribbean Development Bank (with annexes, Protocol to provide for procedure for amendment of article 36 of the Agreement and Final Act of the Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Caribbean Development Bank). Done at Kingston, Jamaica, on 18 October 1969 Authentic text: English. Registered ex officio on 26 January 1970. MULTILATÉRAL Accord portant création de la Banque de développement des Caraïbes (avec annexes, Protocole établissant la procé dure de modification de l'article 36 de l'Accord et Acte final de la Conférence de plénipotentiaires sur la Ban que de développement des Caraïbes). Fait à Kingston (Jamaïque), le 18 octobre 1969 Texte authentique: anglais. Enregistr d©office le 26 janvier 1970. 218 United Nations Treaty Series 1970 AGREEMENT 1 ESTABLISHING THE CARIBBEAN DEVEL OPMENT BANK The Contracting Parties, CONSCIOUS of the need to accelerate the economic development of States and Territories of the Caribbean and to improve the standards of living of their peoples; RECOGNIZING the resolve of these States and Territories to intensify economic co-operation and promote economic integration in the Caribbean; AWARE of the desire of other countries outside the region to contribute to the economic development of the region; CONSIDERING that such regional economic development urgently requires the mobilization of additional financial and other resources; and CONVINCED that the establishment of a regional financial institution with the broadest possible participation will facilitate -

Table 1 Comprehensive International Points List

Table 1 Comprehensive International Points List FCC ITU-T Country Region Dialing FIPS Comments, including other 1 Code Plan Code names commonly used Abu Dhabi 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Aden 5 967 YE include with Yemen Admiralty Islands 7 675 PP include with Papua New Guinea (Bismarck Arch'p'go.) Afars and Assas 1 253 DJ Report as 'Djibouti' Afghanistan 2 93 AF Ajman 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Akrotiri Sovereign Base Area 9 44 AX include with United Kingdom Al Fujayrah 5 971 TC include with United Arab Emirates Aland 9 358 FI Report as 'Finland' Albania 4 355 AL Alderney 9 44 GK Guernsey (Channel Islands) Algeria 1 213 AG Almahrah 5 967 YE include with Yemen Andaman Islands 2 91 IN include with India Andorra 9 376 AN Anegada Islands 3 1 VI include with Virgin Islands, British Angola 1 244 AO Anguilla 3 1 AV Dependent territory of United Kingdom Antarctica 10 672 AY Includes Scott & Casey U.S. bases Antigua 3 1 AC Report as 'Antigua and Barbuda' Antigua and Barbuda 3 1 AC Antipodes Islands 7 64 NZ include with New Zealand Argentina 8 54 AR Armenia 4 374 AM Aruba 3 297 AA Part of the Netherlands realm Ascension Island 1 247 SH Ashmore and Cartier Islands 7 61 AT include with Australia Atafu Atoll 7 690 TL include with New Zealand (Tokelau) Auckland Islands 7 64 NZ include with New Zealand Australia 7 61 AS Australian External Territories 7 672 AS include with Australia Austria 9 43 AU Azerbaijan 4 994 AJ Azores 9 351 PO include with Portugal Bahamas, The 3 1 BF Bahrain 5 973 BA Balearic Islands 9 34 SP include -

An Ancient Maya Hafted Stone Tool from Northern Belize

Volume 1986 Article 24 1986 An Ancient Maya Hafted Stone Tool from Northern Belize Harry J. Shafer [email protected] Thomas R. Hester Center for Archaeological Research, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Cite this Record Shafer, Harry J. and Hester, Thomas R. (1986) "An Ancient Maya Hafted Stone Tool from Northern Belize," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 1986, Article 24. https://doi.org/10.21112/ita.1986.1.24 ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol1986/iss1/24 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Regional Heritage Research at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Ancient Maya Hafted Stone Tool from Northern Belize Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License This article is available in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol1986/iss1/24 AN ANCIENT MAYA HAFTED STONE TOOL FRCJ.1 NORTHERN BELIZE Harry J. -

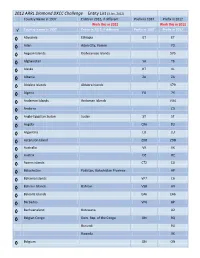

2012 ARRL Diamond DXCC Challenge Entity List

2012 ARRL Diamond DXCC Challenge Entity List (3 Jan, 2012) Country Name in 1937 Entity in 2012, if different Prefix in 1937 Prefix in 2012 Work this in 2012 Work this in 2012 √ Country name in 1937 Entity in 2012, if different Prefix in 1937 Prefix in 2012 ◊ Abyssinia Ethiopia ET ET ◊ Aden Aden City, Yemen 7O ◊ Aegean Islands Dodecanese Islands SV5 ◊ Afghanistan YA T6 ◊ Alaska K7 KL ◊ Albania ZA ZA ◊ Aldabra Islands Aldabra Islands S79 ◊ Algeria FA 7X ◊ Andaman Islands Andaman Islands VU4 ◊ Andorra C3 ◊ Anglo-Egyptian Sudan Sudan ST ST ◊ Angola CR6 D2 ◊ Argentina LU LU ◊ Ascension Island ZD8 ZD8 ◊ Australia VK VK ◊ Austria OE OE ◊ Azores islands CT2 CU ◊ Baluchistan Pakistan, Balochistan Province AP ◊ Bahama Islands VP7 C6 ◊ Bahrein Islands Bahrain VS8 A9 ◊ Balearic islands EA6 EA6 ◊ Barbados VP6 8P ◊ Bechuanaland Botswana A2 ◊ Belgian Congo Dem. Rep. of the Congo ON 9Q Burundi 9U Rwanda 9X ◊ Belgium ON ON ◊ Bermuda Islands VP9 VP9 ◊ Bhutan A5 Bismarck Archipelago Islands off the northeast coast ◊ of Papua New Guinea1 OC-008 Bismarck Archipelago P29 OC-025 Admiralty Islands P29 OC-103 St Matthias Group P29 OC-257 Nuguria Islands P29 OC-258 Coastal Islands North P29 ◊ Bolivia CP CP ◊ Borneo, Netherlands Borneo, Indonesia PK5 YB7 ◊ Brazil PY PY ◊ British Honduras Belize VP1 V3 ◊ British North Borneo Sabah State, Malaysia VS4 9M6 ◊ Brunei V8 ◊ Bulgaria LZ LZ ◊ Burma Myanmar XZ XZ ◊ Cameroons, French Cameroon FE8 TJ ◊ Canada Does not include VO1/VO2 VE VE Canal Zone Any area within 8 km of the NY HP ◊ Panama Canal ◊ Canary Islands EA8 EA8 -

302232 Travelguide

302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.1> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 5 WELCOME 6 GENERAL VISITOR INFORMATION 8 GETTING TO BELIZE 9 TRAVELING WITHIN BELIZE 10 CALENDAR OF EVENTS 14 CRUISE PASSENGER ADVENTURES Half Day Cultural and Historical Tours Full Day Adventure Tours 16 SUGGESTED OVERNIGHT ADVENTURES Four-Day Itinerary Five-Day Itinerary Six-Day Itinerary Seven-Day Itinerary 25 ISLANDS, BEACHES AND REEF 32 MAYA CITIES AND MYSTIC CAVES 42 PEOPLE AND CULTURE 50 SPECIAL INTERESTS 57 NORTHERN BELIZE 65 NORTH ISLANDS 71 CENTRAL COAST 77 WESTERN BELIZE 87 SOUTHEAST COAST 93 SOUTHERN BELIZE 99 BELIZE REEF 104 HOTEL DIRECTORY 120 TOUR GUIDE DIRECTORY 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.2> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.3> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 The variety of activities is matched by the variety of our people. You will meet Belizeans from many cultural traditions: Mestizo, Creole, Maya and Garifuna. You can sample their varied cuisines and enjoy their music and Belize is one of the few unspoiled places left on Earth, their company. and has something to appeal to everyone. It offers rainforests, ancient Maya cities, tropical islands and the Since we are a small country you will be able to travel longest barrier reef in the Western Hemisphere. from East to West in just two hours. Or from North to South in only a little over that time. Imagine... your Visit our rainforest to see exotic plants, animals and birds, possible destinations are so accessible that you will get climb to the top of temples where the Maya celebrated the most out of your valuable vacation time. -

1.0 Overview of IDB Invest Scope of Review BSI Has an Annual Crushing

IDBInvest Belize Sugar Industries Limited 1.0 Overview of IDB Invest Scope of Review BSI has an annual crushing capacity of 1.3 million tons of sugarcane, with an average daily milling throughput of 6,800 tons. The mill is in Tower Hill, Orange Walk District, and receives sugarcane from more than 5,000 independent cane suppliers, of which some 1,000 are women. Ninety per cent of farmers are small holders with farm sizes less than 8 ha, of which 35% are less than 2 ha. BSI produces enough sugar to meet the demand of the domestic sugar market, with the balance exported as raw and food-grade sugar products to refineries in the United Kingdom, United States, Canada and CARICOM. Sugar accounts for 60% of Belize's agricultural exports. BSI also owns and operates a 31.5 MW cogeneration energy power plant (Belcogen) which powers the sugar operations and exports to the national public grid, providing 15% of the country needs (70GWh), increasing Belize’s energy security. The country is heavily reliant on imported energy. BSI agricultural operations and sugar milling facilities are certified by SQF Kosher, Fair Trade, and ProTerra. The latter standard covers all the important challenges relating to large-scale production of agricultural commodities along the whole value chain. It is applicable for all agricultural commodities worldwide, providing compliance with environmental and social criteria as well as Health and Safety Regulations. It also covers key components such as protection of high conservation value areas, protection of children, and of the rights of communities, indigenous people, and small holders. -

Anthropology / Anthropologie/ Antropología

Bibliographical collection on the garifuna people The word garifuna comes from Karina in Arawak language which means “yucca eaters”. ANTHROPOLOGY / ANTHROPOLOGIE/ ANTROPOLOGÍA Acosta Saignes, Miguel (1950). Tlacaxipeualiztli, Un Complejo Mesoamericano Entre los Caribes. Caracas: Instituto de Antropología y Geografía, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad Central. Adams, Richard N. (1956). «Cultural Components of Central America». American Anthropologist, 58, 881- 907. Adams, Sharon Wilcox (2001). The Garifuna of Belize: Strategies of Representation. B.A. Honors Thesis, Mary Washington College. Adams, Sharon Wilcox (2006). Reconstructing Identity: Representational Strategies in the Garifuna Community of Dangriga, Belize. M. A. Thesis, University of Texas, Austin. Agudelo, Carlos (2012). “Qu’est-ce qui vient après la reconnaissance ? Multiculturalisme et populations noires en Amérique latine» in Christian Gros et David Dumoulin Kervran (eds.) Le multiculturalisme au concret. Un modèle latino américain?. Paris: Presses Sorbonne Nouvelle, pp. 267-277. Agudelo, Carlos (2012). «The afro-guatemalan Political Mobilization: Between Identity, Construction Process, Global Influences and Institutionalization» in Jean Rahier (ed) Black Social Movements in Latin America. From Monocultural Mestizaje to Multiculturalism. Miami: Palgrave Macmillan. Agudelo, Carlos (2012). “Los garifunas, identidades y reivindicaciones de un pueblo afrodescendiente de América Central” in CINU-Centro de información de las Naciones Unidas (ed.) Afrodescendencia: aproximaciones contemporáneas desde América Latina y el Caribe, pp. 59-66. http://www.cinu.mx/AFRODESCENDENCIA.pdf viewed 06.04.2012. Agudelo, Carlos (2010). “Génesis de redes transnacionales. Movimientos afrolatinoamericanos en América Central» in Odile Hoffmann (ed.) Política e Identidad. Afrodescendientes en México y América Central. México: INAH, UNAM, CEMCA, IRD, pp. 65-92. Agudelo, Carlos (2011). “Les Garifuna. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) .