Kalinago Ethnicity and Ancestral Knowledge 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern Caribbean Humanitarian Situation Report No

Eastern Caribbean Humanitarian Situation Report No. 9 © UNICEF/Simon (Left): UNSG visited a child friendly space in Dominica. (Right): UNSG interact with children from Barbuda 11 October 2017 Highlights Situation in numbers: Eastern Caribbean countries and overseas territories continue to respond to two devastating category 5 hurricanes - Irma and Maria - which left a 39,000 trail of destruction in Anguilla, Barbuda, British Virgin Islands, Dominica # affected children in Irma and Maria and Turks & Caicos Islands. Dominica is one of the most affected, hence it remains a primary focus of humanitarian efforts. affected countries, of which Education – More than 11,700 school-age children in Anguilla, British 19,800 Virgin Islands and Turks & Caicos Islands returned to class, some of # affected children in Dominica them using temporary learning spaces. A total of 27 of the 67 state primary and secondary schools in Dominica are slated to reopen on 16 October. 2,750 Child Protection - Over 2,800 children received psychosocial support # people who remain sheltered in and/or access to safe child spaces. In Dominica, a safe recreational Dominica space was provided for up to 900 indigenous children of the Kalinago community. Partners were trained to deliver psycho-social support to a population of 12,000 children. In Antigua, 26 new facilitators drawn 1,070 from teachers, social workers and counsellors were trained in Return # children from Dominica and to Happiness programme activities. They will further cascade their Barbuda estimated to be training in Antigua and Barbuda. integrated in schools in Antigua WASH – With water distribution systems still severely compromised in the impacted countries, especially Dominica, UNICEF and partners provided safe drinking water to nearly 35,000 vulnerable people, UNICEF Funding Needs including 9,100 children. -

August 2015 No

C A R I B B E A N On-line C MPASS AUGUST 2015 NO. 239 The Caribbean’s Monthly Look at Sea & Shore (WE) See story on page 20 MIRA NENCHEVA AUGUST 2015 CARIBBEAN COMPASS PAGE 2 NENCHEVA The Caribbean’s Monthly Look at Sea & Shore www.caribbeancompass.com “Pirate ships” AUGUST 2015 • NUMBER 239 in Aruba MCGEARY Youth Sailing Skills for life ......................... 15 SANDERSON NENCHEVA DEPARTMENTS Info & Updates ......................4 The Caribbean Sky ...............26 Business Briefs .......................8 Look Out For… ......................28 Eco-News .............................. 10 Meridian Passage .................28 Regatta News........................ 12 Cooking with Cruisers ..........29 Y2A ......................................... 15 Readers’ Forum .....................30 Seawise ................................. 22 Caribbean Market Place .....33 Cartoons ................................ 24 Calendar of Events ...............36 Panama to Island Poets ...........................24 Classified Ads ....................... 37 Antigua Passage Book Review ......................... 25 Advertisers’ Index .................38 It can be done! ...................... 16 Caribbean Compass is published monthly by Compass Publishing Ltd., P.O. Box 175 BQ, AUGUST 2015 CARIBBEAN COMPASS PAGE 3 Bequia, St. Vincent & the Grenadines. Tel: (784) 457-3409, Fax: (784) 457-3410, [email protected], www.caribbeancompass.com Editor...........................................Sally Erdle Art, Design & Production......Wilfred Dederer [email protected] -

Heritage Education — Memories of the Past in the Present Caribbean Social Studies Curriculum: a View from Teacher Practice Issue Date: 2019-05-28

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/73692 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Con Aguilar E.O. Title: Heritage education — Memories of the past in the present Caribbean social studies curriculum: a view from teacher practice Issue Date: 2019-05-28 Chapter 6: The presence of Wai’tu Kubuli in teaching history and heritage in Dominica 6.1 Introduction Figure 6.1: Workshop at the Salybia Primary School Kalinago Territory, Dominica, January 2016. During my stay in Dominica, I had the opportunity to organize a teachers’ workshop with the assistance of the indigenous people of the Kalinago Territory. Although the teachers interact with Kalinago culture on a daily basis, we decided to explore the teachers’ knowledge of indigenous heritage and to challenge them in activities where they could put their knowledge into practice. We then drew animals, plants, tools and objects that are found in daily life in the Kalinago Territory. Later on in the workshop, we asked teachers about the Kalinago names that were printed on their tag names. Teachers were able to recognize some of these Kalinago names, and sometimes even the stories behind them. In this simple way, we started our workshop on indigenous history and heritage — because sometimes the most useful and meaningful learning resources are the ones we can find in our everyday life. This case study took place in Dominica; the island is also known by its Kalinago name, Wai’tu Kubuli, which means “tall is her body.” The Kalinago Territory is the home of the Kalinago people. -

Yurumein - Homeland Study Guide

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Andrea E. Leland Documentary Collection Center for Black Music Research 2018 Yurumein - Homeland Study Guide Andrea E. Leland Lauren Poluha Paula Prescod Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/leland Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, Communication Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, History Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Music Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. A Documentary Film by NINE MORNING PRODUCTIONS and ANDREA E. LELAND PRODUCTIONS, INC. Producer, Director, Camera: ANDREA E. LELAND Additional Camera: FABIAN GUERRA / GORO TOSHIMA Editor: TOM SHEPARD Sound Edit: BURKE SOUND STUDIO Color Correction: GARY COATES Animation: JON EICHNER/ RAMIRO SEGURA, TIN ROOF PRODUCTIONS Online Editor: HEATHER WEAVER www.yurumeinproject.com/ [email protected] • www.andrealeland.com/ [email protected] Photography credit: Kingsley Roberts Teachers’ Study Guide YURUMEIN – HOMELAND RESISTANCE, RUPTURE & REPAIR: THE CARIBS OF ST VINCENT A documentary film by Andrea E. Leland Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………….............. 3 Introduction ..………………………………………………………………………............. 4 About the filmmaker………………………………………………………............ 5 Featured in the film…………………………………………………….............. 5 Concepts and definitions…………………………………………………………............. 6 Discussion: Tradition and Identity ………........…………………….................. 7 St Vincent -

CALL for PAPERS the Garifuna Heritage Foundation Inc. in Collaboration with UWI Open Campus of St

CALL FOR PAPERS The Garifuna Heritage Foundation Inc. In collaboration with UWI Open Campus of St. Vincent and the Grenadines Presents The 4th ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL GARIFUNA CONFERENCE “Celebrating Our Indigenous History, Heritage and Cultures - From Mainland to Islands and Return: Strengthening links, Forging networks, Claiming Ancestral space” March 7th – 9th, 2017 Kingstown, St. Vincent and the Grenadines The Garifuna are a hybrid of the Kalinago and African people, their histories and their cultures which emerged in the 17th Century on the island of St. Vincent known by the Kalinago as “Yurumein”. A unique culture, it captures the African as well as the Kalinago experience forged together through the crucible of colonial expansionism. The Garifuna, who controlled the island of St. Vincent , resisted the incursion of British Colonialism into St. Vincent for over two hundred years until the majority subjected to forced Exile by the British from St. Vincent to Central America in 1797 after the Second Carib War. Despite this, they survived and thrived and today vibrant communities exist on Mainland Central & North America - Belize, Honduras, Guatemala , Nicaragua and the United States, practicing their Culture and in all cases contributing a significant cultural component to these countries’ national dynamics. The influence of the Indigenous Kalinago culture and people continues to impact the Islands of the Caribbean, particularly Dominica, Trinidad and Martinique. This strand of the Garifuna Heritage represents a unique link with Mainland South America through the Orinoco Basin , now part of Venezuela, where the Kalinago people originated and where many of their communities still thrive. In addition, the mainland African component of the Garifuna culture has placed an indelible print on the manifestations of the Garifuna people in the practicing of their spirituality, music and dance. -

Regional Overview: Impact of Hurricanes Irma and Maria

REGIONAL OVERVIEW: IMPACT OF MISSION TO HURRICANES IRMA AND MARIA CONFERENCE SUPPORTING DOCUMENT 1 The report was prepared with support of ACAPS, OCHA and UNDP 2 CONTENTS SITUATION OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................... 4 KEY FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Overall scope and scale of the impact ....................................................................................... 5 Worst affected sectors ...................................................................................................................... 5 Worst affected islands ....................................................................................................................... 6 Key priorities ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Challenges for Recovery ................................................................................................................. 7 Information Gaps ................................................................................................................................. 7 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RECOVERY ................................................................................ 10 Infrastructure ...................................................................................................................................... -

Afro-Central Americans: T Rediscovering the African Heritage AFRO-CENTRAL AMERICANS • 96/3 T TIONAL REPOR an MRG INTERNA

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R Afro-Central Americans: T Rediscovering the African Heritage AFRO-CENTRAL AMERICANS • 96/3 T TIONAL REPOR AN MRG INTERNA G R M EDITED BY MINORITY RIGHTS GROUP AFRO-CENTRAL AMERICANS: REDISCOVERING THE AFRICAN HERITAGE © Minority Rights Group 1996 Acknowledgements British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Minority Rights Group (MRG) gratefully acknowledges all A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library organizations and individuals who gave financial and other ISBN 1 897693 51 6 ISSN 0305 6252 assistance for this report. Published June 1996 This report has been commissioned and is published by The text of this report was first published in 1995 in No Longer Invisible – MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the issue Afro-Latin Americans Today by Minority Rights Publications which forms its subject. The text and views of the individ- Typeset by Texture ual authors do not necessary represent, in every detail and Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper by MFP Design and Print in all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. THE AUTHORS lator and interpreter at the Universidad Nacional, Heredia, Costa Rica. She is the author and co-author of several pub- JAMEELAH S. MUHAMMAD is currently studying at the lished works and articles. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City. FRANKLIN PERRY is a Costa Rican of Jamaican descent. She is a founding member of the Organization of Africans He holds a licenciatura in English and translation and a BA in the Americas and is the author of numerous articles on in English and education from the Universidad de Costa the African presence in Mexico. -

Origin and Maintenance of Genetic Variation in Black Carib Populations

ORIGIN AND MAINTENANCE OF GENETIC VARIATION IN BLACK CARm POPULATIONS OF ST. VINCENT AND CENTRAL AMERICA M.H.CRAWFORD Department of Anthropology, University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas, U.S.A. INTRODUCTION The Black Caribs of Central America (also known as the Gariftma) provide " tropical example of an evolutionarily successful colonising population. They .....,"eased from fewer than 2000 persons in the year 1800 to more than 80,000 in I"~l~; than 180 years. Primarily through popUlation fission, the five founding IIl1t(~k Carib communities established a total of 54 coastal towns and villages. rhis rapid geographical expansion from the Bay of Honduras to Guatemala, 11I'lt ish Honduras and Nicaragua extended over approximately 1000 kilometers of I "lIt,'al American coastline (Figure 1). The successful colonisation of the coast by the Black Caribs can be .,~plllined in part by: (1) an exceptional level of genetic variation contained in II,,· Irene pool of the founding group; (2) pre-eXisting genetic adaptation against III,dlll'ia; (3) a social organisation which maintained high level of fertility and 1""1\'1 i<~ variation; (4) a unique sequence of historical events. This recent I ~1'''lIsion of the Black Caribs provides an excellent opportunity to explore the IV"'"l1ics and population structure of tropical colonising populations. HmTOR~ALBACKGROUND The Black Caribs originated on St. Vincent Island of the Lesser Antilles as 1I" "lllItlgl1m between Carib/Arawak Amerindians and West Africans (Figure 1). h"I'"lly, St. Vincent Island was settled by Arawaks from South America in "1.1 )(llllul:ely 100 A.D. Between 1200 A.D. -

On Leaving and Joining Africanness Through Religion: the 'Black Caribs' Across Multiple Diasporic Horizons

Journal of Religion in Africa 37 (2007) 174-211 www.brill.nl/jra On Leaving and Joining Africanness Th rough Religion: Th e ‘Black Caribs’ Across Multiple Diasporic Horizons Paul Christopher Johnson University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, Center for Afroamerican and African Studies, 505 S. State St./4700 Haven, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1045, USA [email protected] Abstract Garifuna religion is derived from a confluence of Amerindian, African and European anteced- ents. For the Garifuna in Central America, the spatial focus of authentic religious practice has for over two centuries been that of their former homeland and site of ethnogenesis, the island of St Vincent. It is from St Vincent that the ancestors return, through spirit possession, to join with their living descendants in ritual events. During the last generation, about a third of the population migrated to the US, especially to New York City. Th is departure created a new dia- sporic horizon, as the Central American villages left behind now acquired their own aura of ancestral fidelity and religious power. Yet New-York-based Garifuna are now giving attention to the African components of their story of origin, to a degree that has not occurred in homeland villages of Honduras. Th is essay considers the notion of ‘leaving’ and ‘joining’ the African diaspora by examining religious components of Garifuna social formation on St Vincent, the deportation to Central America, and contemporary processes of Africanization being initiated in New York. Keywords Garifuna, Black Carib, religion, diaspora, migration Introduction Not all religions, or families of religions, are of the diasporic kind. -

Towards a Biography of a Caribbean Island of Death, Grief and Memory

Island Studies Journal, 15(2), 2020, 255-272 Mourning Balliceaux: Towards a biography of a Caribbean island of death, grief and memory Niall Finneran Department of Archaeology, Anthropology and Geography, University of Winchester, UK [email protected] (corresponding author) Christina Welch Department of Theology, Religions and Philosophy, University of Winchester, UK [email protected] Abstract: This contribution considers how a small Caribbean island (Balliceaux, St Vincent and the Grenadines) holds up a mirror to the wider experiences of the Garifuna (‘Black Carib’) peoples who live on the neighbouring island of St Vincent, and in diasporic communities through the Americas. In the late-18th Century Balliceaux was the scene of a genocide orchestrated by the British colonial authorities on the Garifuna, and as a consequence it has become an important place of memory for them, yet it also provokes other emotional responses. We start by taking a broadly phenomenological approach to the analysis of islandscape, emphasising its qualities as an embodied as well as physical entity, and then build upon the notion of embodiment using perspectives drawn from psychological studies of grief and grieving through the lens of grief and death studies. We argue that it is only through deploying such a phenomenological perspective to the study of this Caribbean island that we can discern the metaphors employed by the Garifuna in making sense of this island of death, grief and memory. By drawing on their own understandings of Balliceaux as a base for our theorisations, we offer an original theoretical and decolonised approach to thinking about the character, or sense of place, of a small, yet emotionally significant, Caribbean island. -

Latinos and Afro-Latino Legacy in the United States: History, Culture, and Issues of Identity Refugio I

Professional Agricultural Workers Journal Volume 3 2 Number 2 Professional Agricultural Workers Journal 4-6-2016 Latinos and Afro-Latino Legacy in the United States: HIstory, Culture, and Issues of Identity Refugio I. Rochin University of California, Davis/Santa Cruz, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://tuspubs.tuskegee.edu/pawj Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, Agriculture Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, and the Latina/o Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rochin, Refugio I. (2016) "Latinos and Afro-Latino Legacy in the United States: HIstory, Culture, and Issues of Identity," Professional Agricultural Workers Journal: Vol. 3: No. 2, 2. Available at: http://tuspubs.tuskegee.edu/pawj/vol3/iss2/2 This Reflections and Commentaries is brought to you for free and open access by Tuskegee Scholarly Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Agricultural Workers Journal by an authorized administrator of Tuskegee Scholarly Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEORGE WASINGTON CARVER BANQUET LECTURE; ORIGINALLY DELIVERED AT THE 59TH PROFESSIONAL AGRICULTURAL WORKERS CONFERENCE. REVISED AUGUST 2015* LATINOS AND AFRO-LATINO LEGACY IN THE UNITED STATES: HISTORY, CULTURE, AND ISSUES OF IDENTITY *Refugio I. Rochin1,2 1Smithsonian Center for Latino Initiatives and 2University of California Davis *Email of author: [email protected]; [email protected] Introduction Since my first visit to the campus in 1992, I have looked forward to this event. Tuskegee University is a world famous campus with many firsts in science and higher education. And it gives me great pleasure to speak about Latinos and Afro-Latinos. -

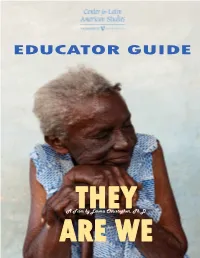

An Educator's Guide to They Are We

THEY A Film by Emma Christopher, Ph.D ARE WE VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES Table of Contents FILM SYNOPSIS ....................................................................................................................................................4 ABOUT THE DIRECTOR ....................................................................................................................................5 DIRECTORS NOTE ..............................................................................................................................................6 AFRICAN SLAVE TRADE IN LATIN AMERICA ...........................................................................................8 AFRO-CUBAN CULTURE AND INFLUENCE .............................................................................................14 LESSON PLANS ..................................................................................................................................................18 AFRO-CUBAN CULTURE .....................................................................................................................................18 AFRO-CUBAN AND AFRO-LATINO COMMUNITIES .............................................................................................20 AFRO-CUBAN MUSIC AND INFLUENCE ...............................................................................................................24 CONTEMPORARY AFRO-LATINOS IN LATIN AMERICA AND USA ........................................................................28