(Colour).Indd 1 17/10/2017 15:03 2 Colouring the Caribbean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yurumein - Homeland Study Guide

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Andrea E. Leland Documentary Collection Center for Black Music Research 2018 Yurumein - Homeland Study Guide Andrea E. Leland Lauren Poluha Paula Prescod Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/leland Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, Communication Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, History Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Music Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. A Documentary Film by NINE MORNING PRODUCTIONS and ANDREA E. LELAND PRODUCTIONS, INC. Producer, Director, Camera: ANDREA E. LELAND Additional Camera: FABIAN GUERRA / GORO TOSHIMA Editor: TOM SHEPARD Sound Edit: BURKE SOUND STUDIO Color Correction: GARY COATES Animation: JON EICHNER/ RAMIRO SEGURA, TIN ROOF PRODUCTIONS Online Editor: HEATHER WEAVER www.yurumeinproject.com/ [email protected] • www.andrealeland.com/ [email protected] Photography credit: Kingsley Roberts Teachers’ Study Guide YURUMEIN – HOMELAND RESISTANCE, RUPTURE & REPAIR: THE CARIBS OF ST VINCENT A documentary film by Andrea E. Leland Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………….............. 3 Introduction ..………………………………………………………………………............. 4 About the filmmaker………………………………………………………............ 5 Featured in the film…………………………………………………….............. 5 Concepts and definitions…………………………………………………………............. 6 Discussion: Tradition and Identity ………........…………………….................. 7 St Vincent -

Kalinago Ethnicity and Ancestral Knowledge 1

Kalinago Ethnicity and Ancestral Knowledge 1 Kalinago Ethnicity and Ancestral Knowledge Kathryn A. Hudepohl Western Kentucky University The Kalinago of Dominica have engaged in various efforts at cultural renewal in the past three decades. In this paper I examine one particular activity, recreated traditional dancing, and analyze how performers combine current and past cultural practices from their own community together with knowledge garnered from other indigenous groups to reinvent dance performances. Such performances represent a recent manifestation of successful cultural renewal in which community members use known resources to re-imagine and recreate meaningful tradition(s). Analysis of recreated traditional dance performances provides insight regarding how some members of the Kalinago community think about and utilize the ancestral knowledge base that forms the wellspring of their identity and reveals the regional and global exchanges that contribute to and enrich processes of cultural renewal. Performers interpret this type of cultural borrowing as a positive strategic maneuver because situating the community in a regional indigenous context bolsters claims to a strong, vibrant Kalinago identity. In this context, both the act of borrowing and the fi nal product are expressions of indigeneity. Protected from the heat of a Caribbean afternoon by the steeply-pitched roof of an open-sided longhouse, three traditionally dressed dancers from the Carib community in Dominica move across the raised stage as they perform a series of dances. Four additional individuals, dressed similarly, ring the back of the stage providing musical accompaniment on drums, a mounted piece of bamboo, and a shak-shak (similar in function to maracas). The director of the ensemble, dressed in western-style clothes, introduces the group and each song to provide cultural context. -

Picturing Antilles' Markets As an Inventory of Human

Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura ISSN: 0120-2456 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de Colombia Colombia LAFONT, ANNE Fabric, Skin, Color: Picturing Antilles’ Markets as an Inventory of Human Diversity Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura, vol. 43, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2016, pp. 121-154 Universidad Nacional de Colombia Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=127146460005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Fabric, Skin, Color: Picturing Antilles’ Markets as an Inventory of Human Diversity* doi: 10.15446/achsc.v43n2.59074 Tela, piel, color: retratando los mercados de las Antillas como un inventario de la diversidad humana Tecido, pele, cor: retratando os mercados das Antilhas como um inventário da diversidade humana anne lafont** Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art Université Paris Est Marne-la-Vallée París, Francia * I would like to thank anonymous readers for precise advice and careful remarks and, as well, two dear colleagues involved in outstanding research concerning textile and art history: Rémi Labrusse and Tristan Weddigen, who made precious suggestions to improve this article. ** [email protected] Artículo de investigación Recepción: 3 de marzo del 2016. Aprobación: 15 de marzo del 2016. Cómo citar este artículo Anne Lafont, “Fabric, Skin, Color: Picturing Antilles’ Markets as an Inventory of Human Diversity”, Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura 43.2 (2016): 121-154. -

The Impact of Skin Color on Atlantic Ethnic Africans in the Eighteenth Century

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2016 "Favorite of Heaven": The mpI act of Skin Color on Atlantic Ethnic Africans in the Eighteenth Century Kimberly V. Jones Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Jones, Kimberly V., ""Favorite of Heaven": The mpI act of Skin Color on Atlantic Ethnic Africans in the Eighteenth Century" (2016). Masters Theses. 2500. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2500 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� EA5u:�ILLINOIS lJN1vER..'iJTY Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may r reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyight; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. -

©2017 Tashima Thomas ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2017 Tashima Thomas ALL RIGHTS RESERVED AN IMPERIAL DIET: FROM CACAO TO COCONUTS – REPRESENTING EDIBLE BODIES IN THE AMERICAS FROM THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT by TASHIMA THOMAS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Art History Written under the direction of Dr. Tatiana Flores And approved by New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION An Imperial Diet: From Cacao to Coconuts – Representing Edible Bodies in the Americas from the Eighteenth Century to the Present By TASHIMA THOMAS Dissertation Director: Dr. Tatiana Flores This dissertation endeavors to prove through a series of visual mediations that the alimentary tract signifies a gastropoetical dialectic between the eater and the eaten. Alimentary discourse is capable of developing a visual language that illustrates the interiority of appetites of empire through the politics of provender. In this study sugar, cacao, pineapples, and coconuts operate as a lens to view the scaffolding of social and artistic strategies. This project is committed to the excavation of image construction, the visual representation of the African Diaspora in the Americas, and understanding the formation of gastronomical narratives through colonial discourse. Anthropologist Sidney W. Mintz suggests that anthropology has the capabilities to answer the outside and inside meanings of food pathways; but so far it has not done so. This dissertation will be able to offer insight into these issues. In a way, this work calls out what I consider obvious omissions regarding the connections between art history, the visual archive, and tropical food pathways by clearly articulating the power of these foods to transform cultures of vision and the induction of a modern world system. -

Imoinda's Shade

Imoinda’s Shade Free West Indian Dominicans, ca. 1770, Agostino Brunias (1728–96) a Imoinda’s Shade Marriage and the African Woman in Eighteenth-Century British Literature, 1759–1808 Lyndon J. Dominique The Ohio State University Press Columbus Copyright © 2012 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dominique, Lyndon Janson, 1972– Imoinda’s shade : marriage and the African woman in eighteenth-century British litera- ture, 1759–1808 / Lyndon J. Dominique. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1185-4 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8142-1185-2 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8142-9286-0 (cd-rom) 1. English literature—18th century—History and criticism. 2. Race in literature. 3. Women, Black, in literature. 4. Marriage in literature. I. Title. PR448.R33D66 2012 820.9'3552—dc23 2011049519 Cover design by Mia Risberg Type set in Adobe Garamond Pro Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For my mother and father, Rita and Victor Dominique a CONTENTS Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction Imoinda, Marriage, Slavery 1 Part One. Imoinda’s Original Shades: African Women in British Antislavery Literature Chapter 1 Altering Oroonoko and Imoinda in Mid-Eighteenth-Century British Drama 27 Chapter 2 Amelioration, African Women, and The Soft, Strategic Voice of Paternal Tyranny in The Grateful Negro 70 Chapter 3 “Between the saints and the rebels”: Imoinda and the Resurrection of the Black African Heroine 104 Part Two. -

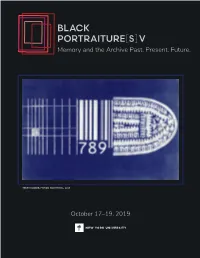

Black Portraitures V: Memory and the Archive Past. Present. Future

V Memory and the Archive Past. Present. Future. TERRY BODDIE,PRISON INDUSTRIAL, 2018 October 17–19, 2019 2 V Memory and the Archive Past. Present. Future. Table of Contents Welcome ..............................................................................................................................................................................................................4 Schedule Grid / Thursday, October 17, 2019...........................................................................................................................................8 Schedule Grid / Friday, October 18, 2019.................................................................................................................................................9 Schedule Grid / Saturday, October 19, 2019.........................................................................................................................................10 Day at a glance / Thursday, October 17, 2019.....................................................................................................................................11 Day at a glance / Friday, October 18, 2019 ...........................................................................................................................................13 Day at a glance / Saturday, October 19, 2019......................................................................................................................................15 Schedule/Abstracts........................................................................................................................................................................................16 -

Qt3j476038 Nosplash 503B781

The Fear of French Negroes Transcolonial Collaboration in the Revolutionary Americas Sara E. Johnson university of california press Berkeley • Los Angeles • London The Fear of French Negroes flashpoints The series solicits books that consider literature beyond strictly national and disciplin- ary frameworks, distinguished both by their historical grounding and their theoretical and conceptual strength. We seek studies that engage theory without losing touch with history and work historically without falling into uncritical positivism. FlashPoints aims for a broad audience within the humanities and the social sciences concerned with mo- ments of cultural emergence and transformation. In a Benjaminian mode, FlashPoints is interested in how literature contributes to forming new constellations of culture and history and in how such formations function critically and politically in the present. Available online at http://repositories.cdlib.org/ucpress. Series Editors: Ali Behdad (Comparative Literature and English, UCLA); Judith Butler (Rhetoric and Comparative Literature, UC Berkeley), Founding Editor; Edward Dimendberg (Film & Media Studies, UC Irvine), Coordinator; Catherine Gallagher (English, UC Berkeley), Founding Editor; Jody Greene (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Susan Gillman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Richard Terdiman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz) 1. On Pain of Speech: Fantasies of the First Order and the Literary Rant, by Dina Al-Kassim 2. Moses and Multiculturalism, by Barbara Johnson, with a foreword by Barbara Rietveld 3. The Cosmic Time of Empire: Modern Britain and World Literature, by Adam Barrows 4. Poetry in Pieces: César Vallejo and Lyric Modernity, by Michelle Clayton 5. Disarming Words: Empire and the Seductions of Translation in Egypt, by Shaden M. Tageldin 6. Wings for Our Courage: Gender, Erudition, and Republican Thought, by Stephanie H. -

Contemporary Pursuits in the Art of Edouard Duval-Carrié

Edouard Duval-Carrié, Soucouyant #3, 2017, 96 in. diameter Decolonizing Refinement: Contemporary Pursuits in the Art of Edouard Duval-Carrié Exhibition co-curated by Paul B. Niell, Michael D. Carrasco, and Lesley A. Wolff In collaboration with Edouard Duval-Carrié February 16 – April 1, 2018 Museum of Fine Arts, Florida State University 250 Fine Arts Building 530 West Call Street Tallahassee, Florida 32306 (850) 644-6836 https://edouardduvalcarriefsu.wordpress.com Table of Contents All contents created by Lesley A. Wolff, Sumaya Ayad, Ashton Langrick, and Emily Thames Common Core Standards…………………………………………………………….……...2 Artist’s Biography...……………… ………………………………………………..………..3 About this Packet.…………………………………………………………………………...4 About the Work: Sugar Conventions…………………………………………….……….….…7 Individual Panels in Sugar Conventions……………………………………………….…..……8 The Haitian Revolution……………………………………………………………..……....11 Agostino Brunias……………………………………………………………….…………..12 Social “Conventions” in Saint Domingue……………………………..……………………13 Haitian Vodou………………………………………………………………….………….15 Prompting Questions: Sugar Conventions……………………………………..……..….……16 About the Work: The Kingdom of This World Etchings…………………..…………………...18 Plot Summary: The Kingdom of This World……………………………………..………….…19 Individual Plates with Corresponding Scenes………………………………..……………..20 Prompting Questions: The Kingdom of This World Etchings…………..……………………...25 North Florida’s Plantation Heritage………………………………………………………..26 Glossary of Terms………………………………………………………………………....28 Student Activities…………………………………………………………………...….…..30 -

![CHRYSALIS [Kris-Uh-Lis]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9949/chrysalis-kris-uh-lis-10259949.webp)

CHRYSALIS [Kris-Uh-Lis]

CHRYSALIS [kris-uh-lis] from Latin chrӯsallis, from Greek khrusallis 1. the obtect pupa of a moth or butterfly 2. anything in the process of developing A CRITICAL STUDENT JOURNAL OF TRANSFORMATIVE ART HISTORY SPECIAL ISSUE: THE VISUAL CULTURE OF SLAVERY (PART 1 OF 2) CULTURAL AND MATERIAL PRACTICE Volume I Number 3 Winter 2016 Editor: Dr. Charmaine A. Nelson, Associate Professor of Art History, McGill University Managing Editor: Anna T. January, MA Art History, McGill University © CHARMAINE A. NELSON AND INDIVIDUAL AUTHORS CHRYSALIS was created by Dr. Charmaine A. Nelson as a vehicle to showcase the most innovative, rigorous, and sophisticated research produced by students within the context of her Art History courses at McGill University (Montreal). Over the years, Nelson observed that undergraduate students in her courses were more than capable of producing exceptional research on par with that of graduate students, and at times even professional academics. Disappointed that the majority of these students were faced with a negligible audience (if any) for their incredible work, with the help of her MA Art History student Anna T. January, Nelson came up with the idea to provide another platform for their research dissemination. CHRYSALIS is that platform! In this the third issue of CHRYSALIS, we say goodbye to the founding Managing Editor, Anna T. January, without whom this publication would simply not exist. Anna has been a wonderful colleague and the success of this publication is due in large part to her intelligence and dedication. Good luck in your future endeavours Anna! CHRYSALIS is an open access, electronic journal that will be published in seven special issues on Nelson’s research website: www.blackcanadianstudies.com The goal of CHRYSALIS is transformation: to publish scholarship that seeks answers to exciting new questions, to encourage students to undertake primary research and to open the discipline of Art History in ways that make it more welcoming to a diverse population of students. -

Fabric, Skin, Color: Picturing Antilles' Markets As An

Fabric, Skin, Color: Picturing Antilles’ Markets as an Inventory of Human Diversity* doi: 10.15446/achsc.v43n2.59074 Tela, piel, color: retratando los mercados de las Antillas como un inventario de la diversidad humana Tecido, pele, cor: retratando os mercados das Antilhas como um inventário da diversidade humana anne lafont** Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art Université Paris Est Marne-la-Vallée París, Francia * I would like to thank anonymous readers for precise advice and careful remarks and, as well, two dear colleagues involved in outstanding research concerning textile and art history: Rémi Labrusse and Tristan Weddigen, who made precious suggestions to improve this article. ** [email protected] Artículo de investigación Recepción: 3 de marzo del 2016. Aprobación: 15 de marzo del 2016. Cómo citar este artículo Anne Lafont, “Fabric, Skin, Color: Picturing Antilles’ Markets as an Inventory of Human Diversity”, Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura 43.2 (2016): 121-154. achsc * Vol. 43 n.° 2, jUl. - diC. 2016 * issn 0120-2456 (impreSo) - 2256-5647 (en línea) * colombia * págs. 121-154 anne lafont [122] abstract The confrontation of West Indies’ variegated and mixed-race populations with painting’s material (canvas and pigments) and the human classificatory systems proper to the era of Encyclopédie’s illustrations prove to be, regarding race and racialization process, a notably interesting research field. Yet, until today, the idea of early modern Caribbean painting has not been raised as such; this is therefore what I propose to study in this article. Indeed, Caribbean painting by means of figurative inventiveness and because of its grounding in the geographical, political, and historical specificity of racial and cultural archipelago, created an original pictorial inventory of human diversity.