Chapter 2: the Idea of Strategic Depth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stranka Demokratske Akcije

2%$9(=(32/,7,ý.(675$1.( Obrazac 5 1D]LYSROLWLþNHVWUDQNHSTRANKA DEMOKRATSKE AKCIJE 2EDYH]HSROLWLþNHVWUDQNHSRNUHGLWLPDLSR]DMPLFDPD GHWDOMLX 1.811,88 KM 2VWDOHREDYH]HSROLWLþNHVWUDQNH GHWDOMLX 1.817.316,10 KM 8.831(2%$9(=(32/,7,ý.(675$1.( 1.819.127,98 KM 2EDYH]HSROLWLþNHVWUDQNHSRNUHGLWLPDLSR]DMPLFDPD Iznos obaveze po 5RNYUDüDQMD osnovu kredita ili Red. Davalac kredita ili Iznos kredita ili Datum Naziv organizacionog dijela Visina rate kredita ili pozajmice na dan br. pozajmnice pozajmice realizacije pozajmice 31.12.2018 1 RO SDA SREDNJE PODRINJE ASA LEASING 33.025,80 20.2.2014 550,43 20.2.2019 1.811,88 UKUPNO: 1.811,88 5.2 Ostale obaveze Iznos obaveze Red. Datum nastanka Naziv organizacionog dijela Povjerilac / obaveza na dan br. obaveze 31122018 1 KO SDA BOSANSKO POSAVSKOG KANTONA doprinosi po ugovoru o djelu 1.1.2018 931,56 2 KO SDA BOSANSKO POSAVSKOG KANTONA ELEKTROPRIVREDA 31.12.2018 29,62 1 od 35 3 KO SDA BOSANSKO POSAVSKOG KANTONA HT ERONET 31.12.2018 84,58 4 KO SDA BOSANSKO POSAVSKOG KANTONA EURO DOO ODŽAK 1.1.2018 152,50 5 OO SDA ODŽAK doprinosi po ugovoru o djelu 1.1.2018 1.688,69 6 OO SDA ORAŠJE DOPRINOSI 31.12.2018 3.285,38 7 OO SDA ORAŠJE BH TELEKOM 31.12.2018 178,00 8 OO SDA ORAŠJE HT MOSTAR 31.12.2018 79,45 9 OO SDA ORAŠJE SERVIS ZA KNJIG USLUGE 31.12.2018 750,00 10 OO SDA ORAŠJE LA BAMBA ORAŠJE 1.1.2018 90,00 11 OO SDA ORAŠJE 60$-/29,û'22 1.1.2018 38,00 12 OO SDA ORAŠJE NAVIS 31.12.2018 2.195,47 13 RO SDA GORNJE PODRINJE OSTALE OBAVEZE 1.1.2018 126,01 14 OO SDA VIŠEGRAD OBAVEZE ZA ZAKUP 31.12.2018 400,00 15 KO SDA SARAJEVO -

Ovdje Mjestu, a Zatim Ga Punih 20 Godina Zalijevao I Njegovao, I Po Hafizi Adisa I Nijaz Sa Sinovima Madžidom I Muazom Kiši I Po Žezi, I Po Danu I Po Noći

Sadržaj 4. Imamo zlatne momke „Šahid“ List učenika 6. 10 jublarno takmičenje učača Kur’ana Medrese „Osman ef. Redžović“ 8. Najbolji sportski pedagog u 2015. godini Čajangrad, Visoko, BiH Tel: 032/745-771; fax:032/745-770 9. Pjesma vjetra e-mail: [email protected] 10. Svaki peti član Nastavničkog vijeća hafiz www.medresa.org 13. Mala Medresa 2015 IZDAVAČ: 17. Zašto gazite ruže bosanske? Medresa „Osman ef. Redžović“ 18. Gdje su danas Ensarije? GLAVNI I ODGOVORNI UREDNIK: 20. Akcija kurban 2015 uspješno realizirana ALIJAGIĆ Harun 22. Aktivnosti Vijeća učenika SEKRETAR REDAKCIJE: 23. Jedan slatkiš, jedno dijete HALILOVIĆ Merjema 24. Od puberteta do identiteta VODITELJ NOVINARSKE SEKCIJE: 25. Ko visoko gađa visočije pogađa UZUNALIĆ Emir, prof. 26. Drugi po redu Dani bosanske kulture LEKTOR: 28. Zasađen drvored lipa uz džamiju DELIBAŠIĆ – KASA Saliha 30. Sastanak redakcija medresanskih listova REDAKTURA: u Mostaru UZUNALIĆ Emir, prof. 32. Vijesti REDAKCIJA: 40. Bez snova ALIJAGIĆ Harun, LUŽIĆ Sulejman, LUŽIĆ Halid, 41. U društvu sa hafizom Ammarom Bašićem HALILOVIĆ Merjema, BERBIĆ Merjem, SULJIĆ Amila, ČAMO Asim, ČEHAJIĆ Irhad, ALKAZ 42. Domovina se brani sjećanjem Alema, PAŠANBEGOVIĆ Ammar, 44. Muhammed a.s. poslanik čovječanstvu GADŽUN Dino, OMANOVIĆ Emina, GANIJA Emin, HUSIKA Ilma, ŽOLJA Ajša 46. Arapski jezik, institucije i perspektive 48. Viceprvaci debatnog takmičenja srednjih VANJSKI SARADNICI: REZAKOVIĆ Dženan, prof., SMAILHODŽIĆ Suad, prof., škola ZDK NUMANAGIĆ Amela, prof. 49. Laži koje živimo DTP I NASLOVNA STRANA: 52. Ne rock grupe nego krvne grupe trebamo MAHMUTOVIĆ Ensar poznavati FOTO: 55. Priča o ljubomornom magarcu RAŠČIĆ Almina 57. Dižem glas, ali njime govorim i sebi 58. Hoću da vam kažem ŠTAMPA: DOBRA KNJIGA 59. -

Islam and Democracy

ISLAM AND DEMOCRACY number 85/86 • volume 22, 2017 EDITED BY ANJA ZALTA MUHAMED ALI POLIGRAFI Editor-in-Chief: Helena Motoh (ZRS Koper) Editorial Board: Lenart Škof (ZRS Koper), Igor Škamperle (Univ. of Ljubljana), Mojca Terčelj (Univ. of Primorska), Miha Pintarič (Univ. of Ljubljana), Rok Svetlič (ZRS Koper), Anja Zalta (Univ. of Ljubljana) Editorial Office: Science and Research Centre Koper, Institute for Philosophical Studies, Garibaldijeva 1, SI-6000 Koper, Slovenia Phone: +386 5 6637 700, Fax: + 386 5 6637 710, E-mail: [email protected] http://www.zrs-kp.si/revije number 85/86, volume 22 (2017) ISLAM AND DEMOCRACY Edited by Anja Zalta and Muhamed Ali International Editorial Board: Th. Luckmann (Universität Konstanz), D. Kleinberg-Levin (Northwestern University), R. A. Mall (Universität München), M. Ježić (Filozofski fakultet, Zagreb), D. Louw (University of the Free State, Bloemfontain), M. Volf (Yale University), K. Wiredu (University of South Florida), D. Thomas (University of Birmingham), M. Kerševan (Filozofska fakulteta, Ljubljana), F. Leoncini (Università degli Studi di Venezia), P. Zovatto (Università di Trieste), T. Garfitt (Oxford University), M. Zink (Collège de France), L. Olivé (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), A. Louth (Durham University), P. Imbert (University of Ottawa), Ö. Turan (Middle-East Technical University, Ankara), E. Krotz (Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán / Universidad Autónoma de Metropolitana-Iztapalapa), S. Touissant (École Normale Supérieure), B. Mezzadri (Université d’Avignon), A. Bárabas -

06 Forum 129-150.Indd

† Muallimov forum † MUALLIMOV FORUM RADIO ISLAMSKE ZAJEDNICE Dževad HODŽIĆ Od prije nekoliko mjeseci Islamska zajednica ima svoj radio, Radio Islamske zajednice BIR. Način na koji su Islamska zajednica u cjelini i svi njeni organi, a posebno Rijaset i Sabor osnovali i pokrenuli ovu instituciju, kao i način na koji se odnosimo prema Radiju BIR govori mnogo o nama. Govori da ne znamo šta je to radio, kakva je to institucija, kakav je to medij, koje mogućnosti pruža, šta zahtijeva u finansijskom, organizacijskom, kadrovskom i konceptualnom pogledu. Govori da nas to i ne zanima, da smo prema svemu ravnodušni, da smo okamenjeni u starim i mrtvim formama, da živimo u davno minulim vremenima i stoljećima, da smo zaostali, da nemamo volje, znanja i snage da se kreativno odnosimo prema izazovima i mogućnostima koje nam se pružaju u aktualnim životnim i kulturnim formama i sadržajima. Prvo, mi ne znamo šta je radio. Evo, može se svako od nas iz Islamske zajednice diskretno testirati. Neka pokuša sam sebi, kao na pitanje šta je to džamija, odgovoriti na pitanje šta je to radio. Odmah ćemo uvidjeti da nam je na pitanje šta je to džamija mnogo lakše odgovoriti. Kod radija smo u nedoumici: Je li to zgrada i tehnika i ljudi ili je to radiopredajnik, ili frekvencija ili sve to zajedno? I šta je to radiofrekvencija koju sada ima Islamska zajednica? Je li to neka materijalna činjenica ili duhovna stvarnost? Spada li frekvencija u alemuš-šehadeh ili u alemu’l-gajb? Kakav je stav šerijatskog prava u pogledu vlasničkih odnosa i raspodjele frekvencija? Kolika je vrijednost radiofrekvencije koju ima Islamska zejednica? Šta je Radio BIR: organ, institucija, ustanova, firma? Drugo, je li Islamska zajednica odgovorno pokrenula Radio BIR? A to prije svega znači je li provela temeljitu konceptualnu, proceduralnu, oraganizacijsku, tehničku i finasijsku elaboraciju rada i djelovanja Radija BIR? Prema onome što je meni poznato i prema onome što radio kao medij znači, pretpostavlja i pruža, Islamska zajednica, odnosno Rijaset i Sabor to nisu učinili. -

Izvještaj O Izrečenim Izvršnim Mjerama Regulatorne Agencije Za Komunikacije Za 2020

IZVJEŠTAJ O IZREČENIM IZVRŠNIM MJERAMA REGULATORNE AGENCIJE ZA KOMUNIKACIJE ZA 2020. GODINU april, 2021. godine SADRŽAJ: 1. UVOD .............................................................................................................................. 3 2. PREGLED KRŠENJA I IZREČENIH IZVRŠNIH MJERA ............................................................. 5 2.1 KRŠENJA KODEKSA O AUDIOVIZUELNIM MEDIJSKIM USLUGAMA I MEDIJSKIM USLUGAMA RADIJA ......... 5 2.2 KRŠENJA KODEKSA O KOMERCIJALNIM KOMUNIKACIJAMA .................................................................... 15 2.3 KRŠENJA PRAVILA O PRUŽANJU AUDIOVIZUELNIH MEDIJSKIH USLUGA I PRAVILA O PRUŽANJU MEDIJSKIH USLUGA RADIJA................................................................................................................................................. 19 2.4 KRŠENJA PRAVILA 79/2016 O DOZVOLAMA ZA DISTRIBUCIJU AUDIOVIZUELNIH MEDIJSKIH USLUGA I MEDIJSKIH USLUGA RADIJA ............................................................................................................................... 24 2.5 KRŠENJA ODREDBI IZBORNOG ZAKONA BiH ............................................................................................. 26 2.6 KRŠENJA PRAVILA I PROPISA U OBLASTI TEHNIČKIH PARAMETARA DOZVOLA ZA PRUŽANJE AVM USLUGA KOJI USLUGE PRUŽAJU PUTEM ZEMALJSKE RADIODIFUZIJE .............................................................................. 29 3. SAŽETAK ....................................................................................................................... -

Džemal Najetović

Curriculum vitae PERSONAL INFORMATION Džemal Najetović Derviša Numića 9, 71.000 Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina +387 30 877328 [email protected] Sex Male | Date of birth19.10.1958. | NationalityBiH WORK ▪ Associate Professor in the research fields, Public Law and International Law WORK EXPERIENCE ▪ Professor at the research fields of Public Law and International Law Faculty of Law, University of Travnik, Kiseljak ▪ Head of specific scientific field International Law ▪ From September 1994 as the professor of Defense homeland until it was shut down on Islamic Pedagogical Academy in Zenica. ▪ From September 2007, assistant professor of Modern Legal and Political Systems at the Law Faculty of the University. ▪ In September 2010, at International Univerrzitetu Philip Noel-Baker in Sarajevo was elected associate professor for the scientific field of diplomacy ▪ In late November 2012, he was elected to the position vandrednog Professor of Contemporary entitled Political Systems EDUCATION AND TRANING 1965. - 1973. Elementary School "Stranjani" near Zenica, 1973. - 1977. Technical secondary military school in Zagreb, traffic technician, 1979. - 1984. Military Technical Academy, in Zagreb, dipl.ing.saobraćaja and transport, the Decision of the Ministry of Science, Education and Sports R Croatian, class UP / I-602-05 / 11-02 / 00001, Reg 533-04-11-0002 from 22.09 .2001.godine determined by the academic title of Master of traffic engineers, 1996/1997. - 2001. Department of Political Science, University of Sarajevo, Master of Political Science 2004. - 2006.. Department of Political Science, University of Sarajevo, Doctor of Political Sciences. Organized by NATO, SFOR, the Office for assistance to Bosnia and Herzegovina in the field of defense (the US Embassy) and the US Institute of Management in the field of defense in 2002 completed a course in management and planning resources for defense. -

Zuhdija-Hasanović.Pdf

BIOGRAFIJA, BIBLIOGRAFIJA, NASTAVNE I DRUGE AKTIVNOSTI ZUHDIJE HASANOVIĆA Ime i prezime Zuhdija Hasanović E-mail adresa i [email protected] kontakt telefon [email protected] Nebočaj 4 71 321 Semizovac tel. 033/431-765 Mjesto i godina Rođen je 23. juna 1967. g. u Križevićima, općina Zvornik. rođenja Obrazovanje - Osnovnu školu završava 1980./81. u Semizovcu, a Gazi Husrev- begovu medresu 1984./85. u Sarajevu; - iste godine se upisuje na tadašnji Islamski teološki fakultet čije studije, uz jednogodišnje služenje vojnog roka, okončava 2. jula 1991. g. odbranom diplomskog rada pod naslovom "Provjera stepena autentičnosti 60-90 hadisa iz djela 'Izbor Poslanikovih hadisa' Jakub- ef. Memića". Mentor na ovom radu mu je bio prof. dr. Omer Nakičević, a rad je ocijenjen najvišom ocjenom; - u januaru 1996. god. upisuje se na postdiplomski studij na FIN-u, katedra Hadis i hadiske znanosti kojeg okončava 26. 5. 1999. god. odbranom magistarskog rada pod naslovom "Muhaddis Mustafa Pruščak i metode odgoja u djelu 'Er-Radi lil-murtedi šerhul-Hadi lil- muhtedi'" pred komisijom u sastavu: prof. dr. Omer Nakičević (mentor), rahm. mr. Ibrahim Džananović (član), rahm. mr. Mesud 1 Hafizović (član) i mr. Ismet Bušatlić (član). Rad je ocijenjen najvišom ocjenom; - doktorirao je, također, na Fakultetu islamskih nauka u Sarajevu 6. 7. 2004. javnom odbranom doktorske disertacije pod naslovom "Rad h. Mehmed-ef. Handžića na polju hadiskih znanosti s osvrtom na djelo 'Izharul-behadža bi šerh Sunen Ibn Madža'" pred komisijom u sastavu: prof. dr. Adnan Silajdžić (predsjednik), prof. dr. Omer Nakičević (mentor), prof. dr. Jusuf Ramić (član), prof. dr. Fuad Sedić (član) i doc. -

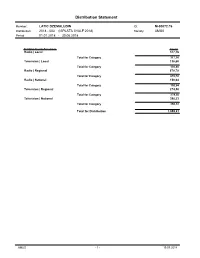

Distribution Statement

Distribution Statement Member: LATIC DZEMALUDIN ID: M-00072.76 Distribution: 2018 - 003 (ISPLATA I HALF 2018) Society: AMUS Period: 01.01.2018 - 30.06.2018 Distributed Amounts Per Category: Amount: Radio | Local 317,16 Total for Category 317,16 Television | Local 136,60 Total for Category 136,60 Radio | Regional 678,78 Total for Category 678,78 Radio | National 150,04 Total for Category 150,04 Television | Regional 274,50 Total for Category 274,50 Television | National 398,53 Total for Category 398,53 Total for Distribution 1.955,61 AMUS - 1 - 19.07.2018 Distribution Statement Member: LATIC DZEMALUDIN ID: M-00072.76 Distribution: 2018 - 003 (ISPLATA I HALF 2018) Society: AMUS Period: 01.01.2018 - 30.06.2018 BEJTULLAHOV CRN OGRTAC ID: W-0000029.77 Role: Rightholders: Society: Share%: ** A LATIC DZEMALUDIN AMUS 55,00 AR BAJRAKTAREVIC MEHMED AMUS 45,00 C TRADITIONAL NS 0,00 Category/Class/Subclass: Amount: Radio | Local/RADIO GRACANICA 0,41 Total for Work 0,41 KAD VJETAR ASKILE ID: W-0002428.53 Role: Rightholders: Society: Share%: ** CA LATIC DZEMALUDIN AMUS 100,00 Category/Class/Subclass: Amount: Radio | Local/RADIO BREZA 0,74 Total for Work 0,74 TENZILA ID: W-0002432.62 Role: Rightholders: Society: Share%: ** A LATIC DZEMALUDIN AMUS 25,00 AR BURHAN SABAN AMUS 33,34 C BURHAN SABAN AMUS 41,66 Category/Class/Subclass: Amount: Radio | Regional/RTV BIHAC - RADIO 2,55 Total for Work 2,55 DRAGI SVOJOJ DRAGOJ LASTI ID: W-0002434.58/1 Role: Rightholders: Society: Share%: ** CA LATIC DZEMALUDIN AMUS 100,00 Category/Class/Subclass: Amount: Radio -

01 Putokazi1-12.Indd

† MUALLIMOV FORUM RADIO ISLAMSKE ZAJEDNICE Dževad HODŽIĆ Od prije nekoliko mjeseci Islamska zajednica ima svoj radio, Radio Islamske zajednice BIR. Način na koji su Islamska zajednica u cjelini i svi njeni organi, a posebno Rijaset i Sabor osnovali i pokrenuli ovu instituciju, kao i način na koji se odnosimo prema Radiju BIR govori mnogo o nama. Govori da ne znamo šta je to radio, kakva je to institucija, kakav je to medij, koje mogućnosti pruža, šta zahtijeva u finansijskom, organizacijskom, kadrovskom i konceptualnom pogledu. Govori da nas to i ne zanima, da smo prema svemu ravnodušni, da smo okamenjeni u starim i mrtvim formama, da živimo u davno minulim vremenima i stoljećima, da smo zaostali, da nemamo volje, znanja i snage da se kreativno odnosimo prema izazovima i mogućnostima koje nam se pružaju u aktualnim životnim i kulturnim formama i sadržajima. Prvo, mi ne znamo šta je radio. Evo, može se svako od nas iz Islamske zajednice diskretno testirati. Neka pokuša sam sebi, kao na pitanje šta je to džamija, odgovoriti na pitanje šta je to radio. Odmah ćemo uvidjeti da nam je na pitanje šta je to džamija mnogo lakše odgovoriti. Kod radija smo u nedoumici: Je li to zgrada i tehnika i ljudi ili je to radiopredajnik, ili frekvencija ili sve to zajedno? I šta je to radiofrekvencija koju sada ima Islamska zajednica? Je li to neka materijalna činjenica ili duhovna stvarnost? Spada li frekvencija u alemuš-šehadeh ili u alemu’l-gajb? Kakav je stav šerijatskog prava u pogledu vlasničkih odnosa i raspodjele frekvencija? Kolika je vrijednost radiofrekvencije koju ima Islamska zejednica? Šta je Radio BIR: organ, institucija, ustanova, firma? Drugo, je li Islamska zajednica odgovorno pokrenula Radio BIR? A to prije svega znači je li provela temeljitu konceptualnu, proceduralnu, oraganizacijsku, tehničku i finasijsku elaboraciju rada i djelovanja Radija BIR? Prema onome što je meni poznato i prema onome što radio kao medij znači, pretpostavlja i pruža, Islamska zajednica, odnosno Rijaset i Sabor to nisu učinili. -

Stranka Demokratske Akcije

2%$9(=(32/,7,ý.(675$1.( Obrazac 5 1D]LYSROLWLþNHVWUDQNHSTRANKA DEMOKRATSKE AKCIJE 2EDYH]HSROLWLþNHVWUDQNHSRNUHGLWLPDLSR]DMPLFDPD GHWDOMLX 0,00 KM 2VWDOHREDYH]HSROLWLþNHVWUDQNH GHWDOMLX 1.694.070,44 KM 8.831(2%$9(=(32/,7,ý.(675$1.( 1.694.070,44 KM 2EDYH]HSROLWLþNHVWUDQNHSRNUHGLWLPDLSR]DMPLFDPD Iznos obaveze po 5RNYUDüDQMD Red. Davalac kredita ili Iznos kredita ili Datum osnovu kredita ili Naziv organizacionog dijela Visina rate kredita ili br. pozajmnice pozajmice realizacije pozajmice na dan pozajmice UKUPNO: 0,00 5.2 Ostale obaveze Iznos obaveze Red. Datum nastanka Naziv organizacionog dijela Povjerilac / obaveza na dan br. obaveze 31122019 1 KO SDA BOSANSKO POSAVSKOG KANTONA ELEKTROPRIVREDA 31.12.2019 204,42 2 KO SDA BOSANSKO POSAVSKOG KANTONA HT MOSTAR 31.12.2019 104,19 3 OO SDA ODŽAK EURO ODŽAK 31.12.2019 372,50 1 od 32 4 OO SDA ORAŠJE BH TELEKOM 31.12.2019 164,45 5 OO SDA ORAŠJE LA BAMBA ORAŠJE 1.1.2019 90,00 6 OO SDA ORAŠJE GRAFOLADE 31.12.2019 151,96 7 OO SDA ORAŠJE 5(*29$ý.$5$'1-$ 31.12.2019 100,00 8 OO SDA ORAŠJE NAVIS 1.1.2019 2.176,30 9 RO SDA GORNJE PODRINJE VODOVOD I KANALIZACIJA 1.1.2019 14,91 10 OO SDA VIŠEGRAD BENO DOO 31.12.2019 169,35 11 KO SDA SARAJEVO ELEKTROPRIVREDA 31.12.2019 305,39 12 KO SDA SARAJEVO BH TELEKOM 31.12.2019 339,08 13 KO SDA SARAJEVO AVAZ 31.12.2019 31,00 14 KO SDA SARAJEVO CENTROTRANS 1.1.2019 1.500,00 15 KO SDA SARAJEVO NOVA GAMA 31.12.2019 117,10 16 KO SDA SARAJEVO 23û,1$67$5,*5$' 31.12.2019 361,80 17 KO SDA SARAJEVO BUNJO DOO 1.1.2019 320,04 18 KO SDA SARAJEVO ARCH DESIGN 1.1.2019 416,52 19 KO -

PATRONS, CLIENTS and FRIENDS the Role of Bosnian Ulama In

Patrons, clients, and friends : the role of Bosnian ulama in the rebuilding of trust and coexistence in Bosnia and Herzegovina Cetin, O. Citation Cetin, O. (2011, September 21). Patrons, clients, and friends : the role of Bosnian ulama in the rebuilding of trust and coexistence in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/17852 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/17852 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). PATRONS, CLIENTS AND FRIENDS The Role of Bosnian Ulama in the Rebuilding of Trust and Coexistence in Bosnia and Herzegovina PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof. mr. P.F. van der Heijden, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op woensdag 21 september 2011 klokke 10:00 uur door Önder Çetin geboren te Meriç in 1979 Promotiecommissie Promotor: prof. dr. T. Atabaki, Leiden University Co-Promotor: prof. dr. A. Bayat, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Referent: prof. dr. K. Asdar Ali, University of Texas Overige leden: prof. dr. L.P.H.M. Buskens, Leiden University prof. dr. M. Kemper, University of Amsterdam prof. dr. J. M. Otto, Leiden University CONTENTS List of Figures, Maps and Tables .............................................................................................. 5 List -

Godišnji Izvještaj Regulatorne Agencije Za Komunikacije Za 2018

GODIŠNJI IZVJEŠTAJ REGULATORNE AGENCIJE ZA KOMUNIKACIJE ZA 2018. GODINU Mart, 2019. godine SADRŽAJ I UVODNE NAZNAKE ......................................................................................................................... 5 II AKTIVNOSTI IZ PODRUČJA EMITOVANJA, TELEKOMUNIKACIJA, UREĐENJA RADIOFREKVENCIJSKOG SPEKTRA, MONITORINGA I PODRUČJA PRAVNIH, FINANSIJSKIH I OPĆIH POSLOVA .................................................................................................... 6 1. PODRUČJE EMITOVANJA ...................................................................................................... 6 1.1. Dozvole iz područja emitovanja ............................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Korisnici dozvola za televizijsko i radijsko emitovanje koje se vrši putem zemaljske radiodifuzije................................................................................................................................. 6 1.1.2 Korisnici Dozvole za televizijsko emitovanje putem drugih elektronskih komunikacijskih mreža ........................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1.3 Saglasnosti za pružanje audiovizuelnih medijskih usluga na zahtjev ................................ 7 1.1.4 Korisnici Dozvole za radijsko emitovanje putem drugih elektronskih komunikacijskih mreža ..........................................................................................................................................