Bloom's Situated Mind in James Joyce's Ulysses: Decoding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1974.Ulysses in Nighttown.Pdf

The- UNIVERSITY· THEAtl\E Present's ULYSSES .IN NIGHTTOWN By JAMES JOYCE Dramatized and Transposed by MARJORIE BARKENTIN Under the Supervision of PADRAIC COLUM Direct~ by GLENN ·cANNON Set and ~O$tume Design by RICHARD MASON Lighting Design by KENNETH ROHDE . Teehnicai.Direction by MARK BOYD \ < THE CAST . ..... .......... .. -, GLENN CANNON . ... ... ... : . ..... ·. .. : ....... ~ .......... ....... ... .. Narrator. \ JOHN HUNT . ......... .. • :.·• .. ; . ......... .. ..... : . .. : ...... Leopold Bloom. ~ . - ~ EARLL KINGSTON .. ... ·. ·. , . ,. ............. ... .... Stephen Dedalus. .. MAUREEN MULLIGAN .......... .. ... .. ......... ............ Molly Bloom . .....;. .. J.B. BELL, JR............. .•.. Idiot, Private Compton, Urchin, Voice, Clerk of the Crown and Peace, Citizen, Bloom's boy, Blacksmith, · Photographer, Male cripple; Ben Dollard, Brother .81$. ·cavalier. DIANA BERGER .......•..... :Old woman, Chifd, Pigmy woman, Old crone, Dogs, ·Mary Driscoll, Scrofulous child, Voice, Yew, Waterfall, :Sutton, Slut, Stephen's mother. ~,.. ,· ' DARYL L. CARSON .. ... ... .. Navvy, Lynch, Crier, Michael (Archbishop of Armagh), Man in macintosh, Old man, Happy Holohan, Joseph Glynn, Bloom's bodyguard. LUELLA COSTELLO .... ....... Passer~by, Zoe Higgins, Old woman. DOYAL DAVIS . ....... Simon Dedalus, Sandstrewer motorman, Philip Beau~ foy, Sir Frederick Falkiner (recorder ·of Dublin), a ~aviour and · Flagger, Old resident, Beggar, Jimmy Henry, Dr. Dixon, Professor Maginni. LESLIE ENDO . ....... ... Passer-by, Child, Crone, Bawd, Whor~. -

James Joyce – Through Film

U3A Dunedin Charitable Trust A LEARNING OPTION FOR THE RETIRED Series 2 2015 James Joyce – Through Film Dates: Tuesday 2 June to 7 July Time: 10:00 – 12:00 noon Venue: Salmond College, Knox Street, North East Valley Enrolments for this course will be limited to 55 Course Fee: $40.00 Tea and Coffee provided Course Organiser: Alan Jackson (473 6947) Course Assistant: Rosemary Hudson (477 1068) …………………………………………………………………………………… You may apply to enrol in more than one course. If you wish to do so, you must indicate your choice preferences on the application form, and include payment of the appropriate fee(s). All applications must be received by noon on Wednesday 13 May and you may expect to receive a response to your application on or about 25 May. Any questions about this course after 25 May should be referred to Jane Higham, telephone 476 1848 or on email [email protected] Please note, that from the beginning of 2015, there is to be no recording, photographing or videoing at any session in any of the courses. Please keep this brochure as a reminder of venue, dates, and times for the courses for which you apply. JAMES JOYCE – THROUGH FILM 2 June James Joyce’s Dublin – a literary biography (50 min) This documentary is an exploration of Joyce’s native city of Dublin, discovering the influences and settings for his life and work. Interviewees include Robert Nicholson (curator of the James Joyce museum), David Norris (Trinity College lecturer and Chair of the James Joyce Cultural Centre) and Ken Monaghan (Joyce’s nephew). -

Ulysses in Paradise: Joyce's Dialogues with Milton by RENATA D. MEINTS ADAIL a Thesis Submitted to the University of Birmingh

Ulysses in Paradise: Joyce’s Dialogues with Milton by RENATA D. MEINTS ADAIL A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY English Studies School of English, Drama, American & Canadian Studies College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham October 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis considers the imbrications created by James Joyce in his writing with the work of John Milton, through allusions, references and verbal echoes. These imbrications are analysed in light of the concept of ‘presence’, based on theories of intertextuality variously proposed by John Shawcross, Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, and Eelco Runia. My analysis also deploys Gumbrecht’s concept of stimmung in order to explain how Joyce incorporates a Miltonic ‘atmosphere’ that pervades and enriches his characters and plot. By using a chronological approach, I show the subtlety of Milton’s presence in Joyce’s writing and Joyce’s strategy of weaving it into the ‘fabric’ of his works, from slight verbal echoes in Joyce’s early collection of poems, Chamber Music, to a culminating mass of Miltonic references and allusions in the multilingual Finnegans Wake. -

Ulysses: the Novel, the Author and the Translators

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 21-27, January 2011 © 2011 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.1.1.21-27 Ulysses: The Novel, the Author and the Translators Qing Wang Shandong Jiaotong University, Jinan, China Email: [email protected] Abstract—A novel of kaleidoscopic styles, Ulysses best displays James Joyce’s creativity as a renowned modernist novelist. Joyce maneuvers freely the English language to express a deep hatred for religious hypocrisy and colonizing oppressions as well as a well-masked patriotism for his motherland. In this aspect Joyce shares some similarity with his Chinese translator Xiao Qian, also a prolific writer. Index Terms—style, translation, Ulysses, James Joyce, Xiao Qian I. INTRODUCTION James Joyce (1882-1941) is regarded as one of the most innovative novelists of the 20th century. For people who are interested in modernist novels, Ulysses is an enormous aesthetic achievement. Attridge (1990, p.1) asserts that the impact of Joyce‟s literary revolution was such that “far more people read Joyce than are aware of it”, and that few later novelists “have escaped its aftershock, even when they attempt to avoid Joycean paradigms and procedures.” Gillespie and Gillespie (2000, p.1) also agree that Ulysses is “a work of art rivaled by few authors in this or any century.” Ezra Pound was one of the first to recognize the gift in Joyce. He was convinced of the greatness of Ulysses no sooner than having just read the manuscript for the first part of the novel in 1917. -

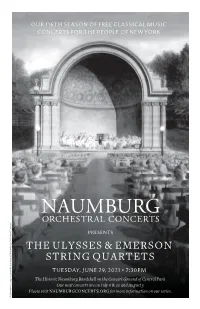

The Ulysses & Emerson String Quartets

OUR 116TH SEASON OF FREE CLASSICAL MUSIC CONCERTS FOR THE PEOPLE OF NEW YORK PRESENTS THE ULYSSES & EMERSON STRING QUARTETS TUESDAY, JUNE 29, 2021 • 7:30PM The Historic Naumburg Bandshell on the Concert Ground of Central Park Our next concerts are on July 6 & 20 and August 3 Please visit NAUMBURGCONCERTS.ORG for more information on our series. ©Anonymous, 1930’s gouache drawing of Naumburg Orchestral of Naumburg Concert©Anonymous, 1930’s gouache drawing TUESDAY, JUNE 29, 2021 • 7:30PM In celebration of 116 years of Free Concerts for the people of New York City - The oldest continuous free outdoor concert series in the world Tonight’s concert is being hosted by classical WQXR - 105.9 FM www.wqxr.org with WQXR host Terrance McKnight NAUMBURG ORCHESTRAL CONCERTS PRESENTS THE ULYSSES & EMERSON STRING QUARTETS RICHARD STRAUSS, (1864-1949) Sextet from Capriccio, Op. 85, (1942) (performed by the Ulysses Quartet with Lawrence Dutton, viola and Paul Watkins, cello) ANTON BRUCKNER, (1824-1896) String Quintet in F major, WAB 112., (1878-79) Performed by the Emerson String Quartet with Colin Brookes, viola III. Adagio, G-flat major, common time -INTERMISSION- DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH, (1906-1975) Two Pieces for String Octet, Op. 11, (1924-25) Performed with the Ulysses Quartet playing the first parts 1. Adagio 2. Allegro molto FELIX MENDELSSOHN, (1809-1847 Octet in E-flat major, Op. 20, (1825) 1. Allegro moderato ma con fuoco (E-flat major) 2. Andante (C minor) 3. Scherzo: Allegro leggierissimo (G minor) 4. Presto (E-flat major) The performance of The Ulysses and Emerson String Quartets has been made possible by a generous grant from The Arthur Loeb Foundation The summer season of 2021 honors the memory of our past President, MICHELLE R. -

A Shorter Finnegans Wake Ed. Anthony Burgess

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. A SHORTER FINNE GANS WAKE ]AMES]OYCE EDITED BY ANTHONY BURGESS NEW YORK THE VIKING PRESS "<) I \J I Foreword ASKED to name the twenty prose-works of the twentieth century most likely to survive into the twenty-first, many informed book-lovers would feel constrained to· include James Joyce's Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. I say "constrained" advisedly, because the choice of these two would rarely be as spontaneous as the choice of, say, Proust's masterpiece or a novel by D. H. Lawrence or Thomas Mann. Ulysses and Finnegans Wake are highly idiosyncratic and "difficult" books, admired more often than read, when read rarely read through to the end, when read through to the end not often fully, or even partially, under stood. This, of course, is especially t-rue of Finnegans Wake. And yet there are people who not only claim to understand a great deal of these books but affirm great love for them-love of an intensity more commonly accorded to Shakespeare or Jane Austen or Dickens. -

Reading the Margins of Joyce's Dubliners

Colby Quarterly Volume 18 Issue 2 June Article 6 June 1982 "Chronicles of Disorder": Reading the Margins of Joyce's Dubliners Joseph C. Voelker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 18, no.2, June 1982, p.126-144 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Voelker: "Chronicles of Disorder": Reading the Margins of Joyce's Dubliner "Chronicles of Disorder": Reading the Margins of Joyce's Dubliners by JOSEPH C. VOELKER lIKE Flaubert's Madame Bovary, Joyce's Dubliners is a book which L derives its power from ambivalence. Of the two writers, Joyce is perhaps the more generous, for while Flaubert could qualify his hatred only in the case of his heroine, Joyce found himself to be of two minds toward an entire city. All his life, Joyce oscillated between injured rage at the parochial closed-mindedness of Dublin and a grudging fondness for its inexplicable and unsteady joie de vivre. It is strange, therefore, that even sensitive readers of Dubliners have agreed to see a very singleminded Joyce lurking behind the realism of his narrative. Perhaps because of the shrillness of his letters at the time, we have come to envision the young Joyce as a nlalignant artist, crafting maledictory leitmotivs out of coffins, priests, books, and gold florins. In such a view, the book is a clinically detailed diagnosis of hemiplegia, and all conclusions concerning the quality of actions within its pages are necessarily foregone. -

“Sirens” Episode of James Joyce's Ulysses

Wiesenmayer, Theodóra angolPark Fugal form and polyphony in the “Sirens” episode of seas3.elte.hu/angolpark James Joyce’s Ulysses © Theodóra Wiesenmayer, ELTE BTK: seas3.elte.hu/angolpark Teodóra Wiesenmayer: Fugal form and polyphony in the “Sirens” episode of James Joyce’s Ulysses . Introduction The emergence of monumental orchestral music in the 19th century resulted in its growing influence upon literary works. Music started to be highly valued because it could express feelings in an undistorted manner. Due to the development of psychoanalytic theories the main concern of the modernist writers was to convey the workings of the human mind. Since the focus of novels shifted from describing outer realities to expressing inner states of mind, language needed to be freed from its semantic rigidity, imitating the natural flow of music (Aronson 20–22). Apart from equating the interior monologue with musical expression (Aronson 22), there was another feature borrowed from music. The departure from traditional storytelling, the impressionistic expression of human thoughts required a shape, which could be borrowed from music. The application of musical forms in order to give a shape to the narrative reached its peak in the “Sirens” episode of Ulysses. This musical frame is part of a larger, mythical frame. While the musical frame makes the “Sirens” episode coherent, the intertextual background of Homer’s Odyssey provides the whole novel’s unity, which “is simply a way of controlling, of ordering, of giving a shape and a significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history” (Eliot 177). This paper deals with the musical structure of the “Sirens” episode, trying to determine its exact form, and to find the reason why Joyce resorted to that specific form. -

Why Joyce Is and Is Not Responsible for the Quark in Contemporary Physics

Papers on Joyce 16 (2010): 19-27 Why Joyce Is and Is Not Responsible for the Quark in Contemporary Physics GERALD E. P. GILLESPIE Abstract The study traces the origins of the term “quark” that Nobel Prize winning physicist Murray Gell-Mann took from Joyce‟s Finnegans Wake. Gillespie argues that the origin of the term is not in an outmoded English verb, as some Joycean critics have proposed, but is rather an instance of “Joyce‟s creative appropriation” of Goethe and Goethe‟s Faust. Keywords: quark, physics, Murray Gell-Mann, Finnegans Wake, Old and Middle English, Goethe‟s Faust. It really should not surprise us that a writer like Joyce, who could entertain the notion of the coincidentia oppositorum, might become the source of such a recondite term as “quark” in the era of quantum mechanics, particle theory, and amazing newer cosmogonies. Joyce enjoys juxtaposing the interlacing polarities of the rival brothers Shaun the postman and Shem the penman who body forth aspects of the world process that are 1 implicated in the larger family romance in Finnegans Wake. The terms of this cabalistic dialectic occur with some WHY JOYCE IS AND IS NOT RESPONSIBLE FOR THE QUARK IN CONTEMPORARY PHYSICS frequency in the parable of the “Ondt” and the “Gracehoper” as 2 told by Shaun in Book III (FW 414 ff) and are anticipated in the long passage near the end of the “Nightletter” in Book II, with the suggestion: “Tell a Friend in a Chatty Letter the Fable of the Grasshopper and the Ant […]” (FW 307.14-15). -

Contingency, Choice and Consensus in James Joyce's

CONTINGENCY, CHOICE AND CONSENSUS IN JAMES JOYCE’S ULYSSES by CARLY HAUFE Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts World Literature CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2015 2 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Carly Haufe candidate for the degree of Master of Arts Committee Chair Florin Berindeanu, Ph.D. Committee Member Chin-Tai Kim, Ph.D. Committee Member Sarah Gridley, M.A., M.F.A. Date of Defense March 20th, 2015 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 4 Contingency, Choice and Consensus in James Joyce’s Ulysses 5 Bibliography 45 4 Contingency, Choice and Consensus in James Joyce’s Ulysses ABSTRACT BY CARLY HAUFE In a work of fiction, we don’t always encounter the contingent in obvious ways. The story is usually told in a w y such that interdependencies of events can be easily overlooked. The distinction of contingent events might be taken for a granted; however, in Joyce’s Ulysses we see an examination of contingency in which the reader is continuously invited to participate. Interpretations of the concept of truth usually indicate a determination by community consensus. The need for an audience to assent to any truth in a fictional work has been identified by most modernist readings of literature, but there is a penumbra, not well- defined, where the author’s intention and the assent of his actual audience intersect—in Ulysses, contingencies of language and of plot might help us to identify these intersections of authorial intent and reader assent. -

Modernism and the Movies | University of Bristol

09/28/21 ENGL30128: Modernism and the Movies | University of Bristol ENGL30128: Modernism and the Movies View Online 60 Free Charlie Chaplin Films Online | Open Culture (no date). Available at: http://www.openculture.com/2011/12/free_charlie_chaplin_films_on_the_web.html. ‘1925: How Sergei Eisenstein Used Montage To Film The Unfilmable - YouTube’ (no date). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g5WbeoP_B8E. ‘Battleship Potemkin (1925) with Eng Subtitles - YouTube’ (no date). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ca0c4vEc5Is. Benyahia, S. C. and Mortimer, C. (2013) ‘Reading a Film’, in Doing film studies: a subject guide for students. London: Taylor and Francis, pp. 67–77. Briggs, A. (19960101) ‘Chaplin’s Charlie and Joyce's Bloom’, Journal of Modern Literature, 20(2). Available at: https://bris.on.worldcat.org/search?databaseList=638&queryString=Austin Briggs, ‘Chaplin’s Charlie and Joyce's Bloom’&clusterResults=true#/oclc/5544093330. Bryher (1998) ‘What Can I Do?’, in Close up, 1927-1933: cinema and modernism. London: Cassell, pp. 286–287. Burkdall, T. B. (2001) ‘Cinema Fakes: Film and Joycean Fantasy’, in Joycean Frames: Film and the Fiction of James Joyce. New York.: Routledge. Available at: https://www-taylorfrancis-com.bris.idm.oclc.org/books/9780203815021/chapters/10.4324/9 780203815021-5. ‘Buster Keaton films - YouTube’ (no date). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=buster+keaton+films. Chaplinesque by Hart Crane | Poetry Foundation (no date). Available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43257/chaplinesque. Doolittle, H. and D, H. (1983) ‘“Projector” and “Projector II”’, in Martz, L. L. (ed.) Collected poems, 1912-1944. New York: New Directions, pp. -

Joseph Strick to Serve As a Regents' Lecturer

Joseph Strick to serve as a Regents' Lecturer January 18, 1978 Academy Award winning director Joseph Strick, who has built successful careers in both the business and film world, will serve as a Regents' Lecturer at the University of California, San Diego January 30 to February 3. Strick, whose film "Interviews with My Lai Veterans" won an Oscar in 1971, will meet with students in seminars and will give three public lectures/film showings while on the campus. His stay is sponsored by Revelle College. During his career, Strick has brought two classic works by novelist James Joyce to the screen. He was producer and director of "Ulysses" which was nominated for an Academy Award in 1968 and last year he produced and directed "A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man." The three lectures and film showings, all free and open to the public, will be held in the Mandeville Auditorium. At the first, scheduled for 4 p.m. Monday, January 30, Strick will show and discuss "A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man." He will show and discuss his film "Ulysses" at 4 p.m. the next day, Tuesday, January 31. In his final public presentation, scheduled for 4 p.m. Thursday, February 2, Strick will show and discuss two other Joyce works adapted for film, "Dubliners" and "Finnegan's Wake." For information contact: Paul Lowenberg, 452-3120 (January 18, 1978) Joseph Strick Films - Director & producer Muscle Beach 1949 The Savage Eye 1959 Awards at Venice, Mannheim and Edinburgh Festivals The Balcony 1963 Academy Award Nomination Ulysses 1967 Academy Award Nomination The Hecklers 1967 Tropic of Cancer 1970 Interviews with My Lai Veterans 1971 Academy Award Road Movie 1974 A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man 1977 Films - Producer The Boy and the Eagle Ring of Bright Water The Darwin Adventure Stage Plays Gallows Humor 1965 Dublin Theater Festival Aristophanes 1966 Royal Shakespeare Co-Stratford upon Avon Other Enterprises Founder and Board Chairman, Electrosolids Corp.