GOAN INQUISITION – Hindus Victims (1560-1820)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

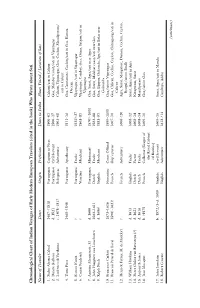

Who W Rote About Sati Name Of

Chronological Chart of Indian Voyages of Early Modern European Travelers (cited in the book) Who Wrote about Sati Name of Traveler Dates Origin Profession Dates in India Places Visited / Location of Sati 1. Pedro Alvares Cabral 1467–?1518 Portuguese Captain of Fleet 1500–01 Calicut/sati in Calicut 2. Duarte Barbosa d. 1521 Portuguese Civil Servant 1500–17 Goa, Malabar Coast/sati in Vijaynagar 3. Ludovico di Varthema c. 1475–1517 Bolognese Adventurer 1503–08 Calicut, Vijaynagar, Goa, Cochin, Masulipatam/ sati in Calicut 4. Tome Pires 1468–1540 Portuguese Apothecary 1511–16 Goa, Cannanore, Cochin/sati in Goa, Kanara, Deccan 5. Fernao Nuniz ? Portuguese Trader 1535?–37 Vijaynagar/sati in Vijaynagar 6. Caesar Frederick ? Venetian Merchant 1563–81 Vijaynagar, Cambay, Goa, Orissa, Satgan/sati in Vijaynagar 7. Antoine Monserrate, SJ d. 1600 Portuguese Missionary 1570?–1600 Goa, Surat, Agra/sati near Agra 8. John Huyghen van Linschoten 1563–1611 Dutch Trader 1583–88 Goa, Surat, Malabar coast/sati near Goa 9. Ralph Fitch d. 1606? English Merchant 1583–91 Goa, Bijapur, Golconda, Agr/sati in Bidar near Golconda 10. Francesco Carletti 1573–1636 Florentine Court Official 1599–1601 Goa/sati in Vijaynagar 11. Francois Pyrard de Laval 1590?–1621? French Ship’s purser 1607–10 Goa, Calicut, Cochin, Ceylon, Chittagong/sati in Calicut 12. Henri de Feynes, M. de Montfort ? French Adventurer 1608–?20 Agra, Surat, Mangalore, Daman, Cochin, Ceylon, Bengal/sati in Sindh 13. William Hawkins d. 1613 English Trader 1608–12 Surat, Agra/sati in Agra 14. Pieter Gielisz van Ravesteyn (?) d. 1621 Dutch Factor 1608–14 Nizapatam, Surat 15. -

Download Release 15

BIBLICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE Gordon E. Christo RELEASE15 The History of the Seventh-day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists Gordon E. Christo Biblical Research Institute Silver Spring, Maryland Copyright © 2020 by the Biblical Research Institute Silver Spring, Maryland www.adventistbiblicalresearch.org General editor: Ekkehardt Mueller Editor: Clinton Wahlen Managing editor: Marly Timm Editorial assistance and layout: Patrick V. Ferreira Copy editor: Schuyler Kline Author: Christo, Gordon Title: Te History of the Seventh-day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists Subjects: Sabbath - India Sabbatarians - India Call Number: V125.S32 2020 Printed in the U.S.A. ISBN 978-0-925675-42-2 Contents Introduction ............................................................................... 1 Early Presence of Jews in India ............................................. 3 Bene Israel ............................................................................. 3 Cochin Jews ........................................................................... 4 Early Christianity in India ....................................................... 6 Te Report of Pantaneus ................................................... 7 “Te Doctrine of the Apostles” ........................................ 8 Te Acts of Tomas ........................................................... 8 Traditions of the Tomas Christians ............................... 9 Tomas Christians and the Sabbath ....................................... 10 -

Conversion in the Pluralistic Religious Context of India: a Missiological Study

Conversion in the pluralistic religious context of India: a Missiological study Rev Joel Thattupurakal Mathai BTh, BD, MTh 0000-0001-6197-8748 Thesis submitted for the degree Philosophiae Doctor in Missiology at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University in co-operation with Greenwich School of Theology Promoter: Dr TG Curtis Co-Promoter: Dr JJF Kruger April 2017 Abstract Conversion to Christianity has become a very controversial issue in the current religious and political debate in India. This is due to the foreign image of the church and to its past colonial nexus. In addition, the evangelistic effort of different church traditions based on particular view of conversion, which is the product of its different historical periods shaped by peculiar constellation of events and creeds and therefore not absolute- has become a stumbling block to the church‘s mission as one view of conversion is argued against the another view of conversion in an attempt to show what constitutes real conversion. This results in competitions, cultural obliteration and kaum (closed) mentality of the church. Therefore, the purpose of the dissertation is to show a common biblical understanding of conversion which could serve as a basis for the discourse on the nature of the Indian church and its place in society, as well as the renewal of church life in contemporary India by taking into consideration the missiological challenges (religious pluralism, contextualization, syncretism and cultural challenges) that the church in India is facing in the context of conversion. The dissertation arrives at a theological understanding of conversion in the Indian context and its discussion includes: the multiple religious belonging of Hindu Christians; the dual identity of Hindu Christians; the meaning of baptism and the issue of church membership in Indian context. -

Download Individual TIFF Images for Personal Use

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title From Inquisition to E-Inquisition: A Survey of Online Sources on the Portuguese Inquisition Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05k4h9qb Journal Journal of Lusophone Studies, 4(2) ISSN 2469-4800 Author Pendse, Liladhar Publication Date 2020 DOI 10.21471/jls.v4i2.241 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California From Inquisition to E-Inquisition: A Survey of Online Sources on the Portuguese Inquisition LILADHAR R. PENDSE University of California, Berkeley Abstract: The Portuguese Inquisition in the colonies of the Empire remains understudied due to a lack of primary source materials that are available the researchers and educators. The advances in digital technologies and the current drive to foster Open Access have allowed us to understand better the relations among the complex set of circumstances as well as the mechanisms that, in their totality, represent the Portuguese Inquisition. The present paper seeks to answer questions that vary from describing these resources to identifying the institutions that created them. Digitized resources serve as a surrogate of the originals, and we can leverage the access to these electronic surrogates and enhance our understanding of the mechanisms of inquisition through E-Inquisitional objects in pedagogy and research. Keywords: Empire, Brazil, India, Africa, archives, open access The study of the history of the Portuguese Inquisition and its institutions has acquired importance in the context of early efforts to convert, indoctrinate, organize and “civilize” the large native and indigenous populations over the vast global expanse of the Portuguese Empire. From the beginning, the Portuguese Crown formed an alliance with the Catholic Church to promote proselytization in its early colonial acquisitions in India. -

Day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-Day Adventists

The History of the Seventh- day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists Biblical Research Institute Release – 15 Gordon E. Christo The History of the Seventh- day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists Gordon E. Christo Biblical Research Institute Silver Spring, Maryland Copyright © 2020 by the Biblical Research Institute Silver Spring, Maryland www.adventistbiblicalresearch.org General editor: Ekkehardt Mueller Editor: Clinton Wahlen Managing editor: Marly Timm Editorial assistance and layout: Patrick V. Ferreira Copy editor: Schuyler Kline Author: Christo, Gordon Title: Te History of the Seventh-day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists Subjects: Sabbath - India Sabbatarians - India Call Number: V125.S32 2020 Printed in the U.S.A. by the Pacifc Press Publishing Association Nampa, ID 83653-5353 ISBN 978-0-925675-42-2 Contents Introduction ............................................................................... 1 Early Presence of Jews in India ............................................. 3 Bene Israel ............................................................................. 3 Cochin Jews ........................................................................... 4 Early Christianity in India ....................................................... 6 Te Report of Pantaneus ................................................... 7 “Te Doctrine of the Apostles” ........................................ 8 Te Acts of Tomas .......................................................... -

Knight of the Renaissance: D

THE NEW CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF INDIA The Portuguese in India Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008 THE NEW CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF INDIA General editor GORDON JOHNSON Director, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of Selwyn College Associate editors C. A. BAYLY Smuts Reader in Commonwealth Studies, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of St Catharine's College and JOHN F. RICHARDS Professor of History, Duke University Although the original Cambridge History of India, published between 1922 and 1937, did much to formulate a chronology for Indian history and de- scribe the administrative structures of government in India, it has inevitably been overtaken by the mass of new research published over the last fifty years. Designed to take full account of recent scholarship and changing concep- tions of South Asia's historical development, The New Cambridge History of India will be published as a series of short, self-contained volumes, each dealing with a separate theme and written by a single person. Within an overall four-part structure, thirty complementary volumes in uniform format will be published during the next five years. As before, each will conclude with a substantial bibliographical essay designed to lead non-specialists further into the literature. The four parts planned are as follows: I The Mughals and their Contemporaries. II Indian States and the Transition to Colonialism. Ill The Indian Empire and the Beginnings of Modern Society. IV The Evolution of Contemporary South Asia. A list of individual titles in preparation will be found at the end of the volume. Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008 Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008 Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008 THE NEW CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF INDIA I • 1 The Portuguese in India M. -

MITAGARS of GOA (A Sociological Study of a Community in Transition) E)2? 6Q

-7/ MITAGARS OF GOA (A Sociological Study of a Community in Transition) e)2? 6q \o By Rey a Sequega Jo CrJa'A‘\IJA \ \k\t QA\\ lutAko, (muatigidi 9K r7A Thesis Submitted for the Award of the Degree of Doctor o Philosophy in Sociology Al rkcAo co- I- 4-60 Department of Sociology Goa University GOA December 2009 DECLARATION I, Ms. Reyna Sequeira, hereby declare that this thesis entitled "Mitagars of Goa (A Sociological Study of a Community in Transition)" is the outcome of my own study undertaken under the guidance of Dr. R. B. Patil, Reader and Head, Department of Sociology, M.E.S. College of Arts and Commerce, Zuarinagar, Goa and Dr. Ganesha Somayaji, Head Department of Sociology, Goa University. It has not previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma or certificate of this or any other university. I have duly acknowledged all the sources used by me in the preparation of this thesis. Place: Goa University Reyna Sequeira Date: ii • CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled "Mitagars of Goa (A Sociological Study of a Community in Transition)" is the record of the original work done by Reyna Sequeira under our guidance. The results of the research presented in this thesis have not previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma or certificate of this or any other university. Place: Goa University Dr. R. B. Patil Ph. D Guide and Reader Date: 28'42=2009— M.E.S. College of Arts and Commerce, (1) - Zuarinagar, Goa – 403 726 Dr. -

Persecution of Hindus - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Persecution of Hindus from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

12/15/2014 Persecution of Hindus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Persecution of Hindus From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Persecution of Hindus refers to the religious persecution inflicted upon Hindus. In modern times, Hindus in the Muslim-majority regions of Kashmir, Pakistan, Bangladesh and others have also suffered persecution. Contents 1 Medieval 1.1 Persecution by Muslim Rulers 1.1.1 By Arabs 1.1.2 Mahmud of Ghazni 1.1.3 Timur's campaign against India 1.1.4 Delhi Sultanate 1.1.4.1 Firuz Shah Tughlaq 1.1.5 In the Mughal empire 1.1.6 Haidar Ali and Tipu Sultan 1.1.7 In Kashmir 1.2 During European rule of the Indian subcontinent 1.2.1 Goa 1.2.2 British Colonial India 2 Modern 2.1 Partition of India 2.1.1 Direct Action Day 2.1.2 Naokhali Riots 2.1.3 During the era of Nizam state of Hyderabad 2.1.4 Pakistan 2.1.4.1 1971 Bangladesh genocide 2.2 Contemporary persecution 2.2.1 Persecution by Buddhists 2.2.1.1 Bhutan 2.2.2 South Asia 2.2.2.1 Republic of India 2.2.2.1.1 Jammu and Kashmir 2.2.2.1.2 Northeast India 2.2.2.1.3 Punjab http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persecution_of_Hindus 2.2.2.1.4 Kerala 1/33 12/15/2014 Persecution of Hindus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 2.2.2.1.4 Kerala 2.2.2.2 Bangladesh 2.2.2.3 Pakistan 2.2.2.3.1 Pakistan Studies curriculum issues 2.2.2.3.2 Forced conversions 2.2.2.3.3 Temple Destruction 2.2.2.3.4 Discrimination due to the rise of Taliban 2.2.2.4 Afghanistan 2.2.2.5 Sri Lanka 2.2.3 In other countries 2.2.3.1 Germany 2.2.3.2 Italy 2.2.3.3 Kazakhstan 2.2.3.4 Malaysia 2.2.3.5 Saudi Arabia 2.2.3.6 Fiji 2.2.3.7 Trinidad & Tobago 2.2.3.8 South Africa 2.2.3.9 United States 3 See also 4 Notes 5 References 6 External links Medieval Persecution by Muslim Rulers By Arabs Muslim conquest of the Indian subcontinent began during the early 8th century, when the Umayyad governor of Damascus, Hajjaj responded to a casus belli provided by the kidnapping of Muslim women and treasures by pirates off the coast of Debal,[1] by mobilising an expedition of 6,000 cavalry under Muhammad bin-Qasim in 712 CE. -

Early Modern Goa Indian Trade, Transcultural Medicine, and the Inquisition

Early modern Goa Indian trade, transcultural medicine, and the Inquisition BINDU MALIECKAL ortugal’s introduction of the Inquisition to India in 1560 placed the lives of Jews, New PChristians, and selected others labelled ‘heretics’, in peril. Two such victims were Garcia da Orta, a Portuguese New Christian with a thriving medical practice in Goa, and Gabriel Dellon, a French merchant and physician. In scholarship, Garcia da Orta and Gabriel Dellon’s texts are often examined separately within the contexts of Portuguese and French literature respectively and in terms of medicine and religion in the early modern period. Despite the similarities of their train- ing and experiences, da Orta and Dellon have not previously been studied jointly, as is attempted in this article, which expands upon da Orta and Dellon’s roles in Portuguese India’s international commerce, especially the trade in spices, and the collaborations between Indian and European physicians. Thus, the connection between religion and food is not limited to food’s religious and religio-cultural roles. Food in terms of spices has been at the foundations of power for ethno- religious groups in India, and when agents became detached from the spice trade, their downfalls were imminent, as seen in the histories of Garcia da Orta and Gabriel Dellon. Early modern Goa through the eyes of Garcia da Orta and Gabriel Dellon In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Indian textiles, wood, gems, and spices were exported to the Middle East, Africa, and Southeast Asia. Mingling with merchants and doctors from across the Indian Ocean were Europeans who were merchants and doctors themselves. -

Conversion Religions and Multi Religious Entanglements Booklet

“Conversion” Religions and Multi-Religious Entanglements in South Asia (8th to 19th c.): Contexts and Perspectives 25 April 2019 Room 737 - 54 boulevard Raspail 75006 Paris Workshop organized by Ines G. Županov “Conversion” Religions and Multi-Religious Entanglements in South Asia (8th to 19th c.): Contexts and Perspectives 25 April 2019 9:00 | Welcome Breakfast 9:30 | Zoé Headley (CNRS, CEIAS) Welcome Address Ines G. Županov (CNRS, CEIAS) Introduction 9:45-10:25 | Istvan Perczel (CEU, Budapest) A new perspective on the ninth-century Christian copper plates: the testimony of the indirect text tradition 10:25- 11:05 | Radu Mustaţă (CEU, Budapest) Entangled literary genres: Jesuit accommodatio and Syriac paideia in Malabar, in the times of the Synod of Diamper (1599) 11:05- 11:20 | tea/coffee 11:20-12:00 | Ophira Gamliel (Theology and Religious Studies, University of Glasgow) Coastal Judaism of the South Asian Cosmopoleis: Transregional Networks, Continuities, and Change 1200s-1700s 12:00-13:00 | lunch 13:00-13:40 | Manu V. Devadevan (Indian Institute of Technology at Mandi) Religious Encounters in the Context of Changing Systems of Knowledge 13:40-14:20 | Mahmood Kooria (Leiden University) Matrilineal and Oceanic Encounters: Indic-Abrahamic Entanglements in Premodern Southwest India 14:20-15:00 | Torsten Tschacher (FU, Berlin) Translation, Islam, and the Formulation of ‘Religious’ Difference in Early Modern South India 15:00-15:15 | tea/coffee 15:15-15:55 | Carsten Wilke (CEU, Budapest) The Archives of the Goa Inquisition: State of the -

New Christians, Converted Hindus, Jesuits, and the Inquisition

Journal of Jesuit Studies 8 (2021) 195-213 New Christians, Converted Hindus, Jesuits, and the Inquisition José Eduardo Franco Open University of Portugal, Department of Social Sciences and Management, Lisbon, Portugal [email protected] Célia Tavares State University of Rio de Janeiro, Department of Human Sciences, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil [email protected] Abstract This paper analyses the complex relationship between Jesuits, New Christians, converted Hindus, and the Inquisition. The collaboration of Jesuits with the Holy Office did not prevent voices from being raised within the Society of Jesus against the tribunal’s practices, which were observed with caution by the first Jesuit leaders. For their part, conversos were initially welcomed into the Society and even assumed high positions in the Society, such as the second superior general. Despite the difficult history of intolerance and inquisitorial persecution against New Christians, in the seventeenth century, Jesuits in Portugal became prominent advocates of their cause. In turn, Hindu conversion strategies fueled disputes and tensions between the Society of Jesus and the Inquisition of Goa. Their strained relations make these disputes an important historiographical subject for understanding many of the plots and dramas of Portuguese society under the Old Regime. Keywords Inquisition – conversos – Hindus – Jesuits – Portugal – Goa © José Eduardo Franco and Célia Tavares, 2021 | doi:10.1163/22141332-0802P003 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the prevailingDownloaded cc-by-nc-nd from Brill.com09/29/20214.0 license. 02:34:18AM via free access 196 franco and tavares Preliminary Considerations When studying the tense relations that existed between two institutions within the Catholic Church—the Inquisition and the Society of Jesus—one should bear in mind that the latter was established while coming under fire from the former. -

Newman, Robert S. 1999. the Struggle for A

Newman, Robert S. 1999. The Struggle for a Goan Identity. In: Dantas, Norman (ed.), The Transforming of Goa. Pp. 17-42. The Other India Press, Mapusa, Goa. ~ J} :i-\~~::~1)~~::,~ ~ ~: >~~'~:; i «;~ ~•- .,::•%"i~o~~-~t),:: ~ -o/ ~~:i~:~~~fllt~~ Struggle for a <;;,} "(::,;c.;;,-·<.':.>, .- ' .·;::(Joan Identity Robert S. Newman* ~.. -""""Y-'·M-• Qoa became the 25th state in the Repub ..,.,.,.,h,~n.n><months earlier, Konkani had been made "'e-.nt••JGhP. small temtory on India's west coast, south was a lan:dm~k year in Goan history, the ·_paJn;ll~l"tlt¥- was officially recognised. Goa became a ~;~a;~~a•l;iOJu•'~-lin~:u.I:stic states and her regional c~ ~i:W41t'gi.,ren. :permanent acknowledgement by the Union two things. First, I want to attempt a limit J(ll~nl;lcy. This.is very difficult -because I do not "f!:"'~""'-"· ... tbipg as the 'Goan ~nd'. There is no una- .. CQnstitqtes a 'G()ari' or 'Goan-ness', . nati(malism (or political iden- .._ places. Malcolm Yapp1 ex- '""'-~·'~'··"~~ n,a:tio,n,8llsm, classing the theories into w~tWJ~a.t•. reac~ve and mOdernising. While each nUJ()n.eu~s andthe.~ments of each can be tha,t moderUjsmg theories-those de ""'h"''"'.,· tradition and modernity plus the role ~u;:a.p•~·'!>'bridge the gap betWeen them ...-,.,.,,,.-;"· not a review of theories of po- ijcaJ:riilil.ation ofhow Goan identity and self .;.·...+:··~"·'*'• years, from the time Iri.dia gained : ~' evolving definition of the Goan (Vol.77, No.1, Jan. 1989) under 'l'h·rnnr>· The Cultural Basis of Goan I.I!Aiig£~tf1Jropot()~~.