Conversion in the Pluralistic Religious Context of India: a Missiological Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stenographer (Post Code-01)

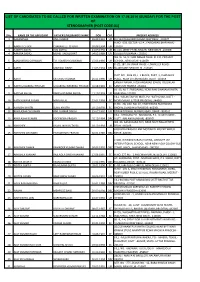

LIST OF CANDIDATES TO BE CALLED FOR WRITTEN EXAMINATION ON 17.08.2014 (SUNDAY) FOR THE POST OF STENOGRAPHER (POST CODE-01) SNo. NAME OF THE APPLICANT FATHER'S/HUSBAND'S NAME DOB CAT. PRESENT ADDRESS 1 AAKANKSHA ANIL KUMAR 28.09.1991 UR B II 544 RAGHUBIR NAGAR NEW DELHI -110027 H.NO. -539, SECTOR -15-A , FARIDABAD (HARYANA) - 2 AAKRITI CHUGH CHARANJEET CHUGH 30.08.1994 UR 121007 3 AAKRITI GOYAL AJAI GOYAL 21.09.1992 UR B -116, WEST PATEL NAGAR, NEW DELHI -110008 4 AAMIRA SADIQ MOHD. SADIQ BHAT 04.05.1989 UR GOOSU PULWAMA - 192301 WZ /G -56, UTTAM NAGAR NEAR, M.C.D. PRIMARY 5 AANOUKSHA GOSWAMI T.R. SOMESH GOSWAMI 15.03.1995 UR SCHOOL, NEW DELHI -110059 R -ZE, 187, JAI VIHAR PHASE -I, NANGLOI ROAD, 6 AARTI MAHIPAL SINGH 21.03.1994 OBC NAJAFGARH NEW DELHI -110043 PLOT NO. -28 & 29, J -1 BLOCK, PART -1, CHANAKYA 7 AARTI SATENDER KUMAR 20.01.1990 UR PLACE, NEAR UTTAM NAGAR, DELHI -110059 SANJAY NAGAR, HOSHANGABAD (GWOL TOLI) NEAR 8 AARTI GULABRAO THOSAR GULABRAO BAKERAO THOSAR 30.08.1991 SC SANTOSHI TEMPLE -461001 I B -35, N.I.T. FARIDABAD, NEAR RAM DHARAM KANTA, 9 AASTHA AHUJA RAKESH KUMAR AHUJA 11.10.1993 UR HARYANA -121001 VILL. -MILAK TAJPUR MAFI, PO. -KATHGHAR, DISTT. - 10 AATIK KUMAR SAGAR MADAN LAL 22.01.1993 SC MORADABAD (UTTAR PRADESH) -244001 H.NO. -78, GALI NO. 02, KHATIKPURA BUDHWARA 11 AAYUSHI KHATRI SUNIL KHATRI 10.10.1993 SC BHOPAL (MADHYA PRADESH) -462001 12 ABHILASHA CHOUHAN ANIL KUMAR SINGH 25.07.1992 UR RIYASAT PAWAI, AURANGABAD, BIHAR - 824101 VILL. -

How the Vision of the Serampore Quartet Has Come Full Circle

Oxford Centre for Christianity and Culture, Centre for Baptist History and Heritage and Baptist Historical Society The heritage of Serampore College and the future of mission From the Enlightenment to modern missions: how the vision of the Serampore Quartet has come full circle John R Hudson 20 October 2018 The vision of the Serampore Quartet was an eighteenth century Enlightenment vision involving openness to ideas and respect for others and based on the idea that, for full understanding, you need to study both the ‘book of nature’ and the ‘book of God.’ Serampore College was a key component in the working out of this wider vision. This vision was superseded in Britain by the racist view that European civilisa- tion is superior and that Christianity is the means to bring civilisation to native peoples. This view had appalling consequences for native peoples across the Empire and, though some Christians challenged it, only in the second half of the twentieth century did Christians begin to embrace a vision more respectful of non-European cultures and to return to a view of the relationship between missionaries and native peoples more akin to that adopted by the Serampore Quartet. 1 Introduction Serampore College was not set up in 1818 as a theological college though ministerial training was to be part of its work (Carey et al., 1819); nor was it a major part, though it remains the most visible legacy of, the work of the Serampore Quartet.1 Rather it came as an outgrowth of the wider vision of the Serampore Quartet — a wider vision which, I will argue, arose from the eighteenth century Enlightenment and which has been rediscovered as the basis for mission in the second half of the twentieth century. -

June 7, 2011 Dr. Roy Taylor Stated Clerk of the Presbyterian Church In

June 7, 2011 Dr. Roy Taylor Stated Clerk of the Presbyterian Church in America Office of the Stated Clerk Administrative Committee 1700 North Brown Road, Suite 105 Lawrenceville, GA 30043 Dear Dr. Taylor, Warm greetings in the precious name of Jesus Christ. I am an Iranian Christian and have been involved in ministry among Muslims for fifty years. I served for 18 years with the United Bible Societies, being heavily involved in Scripture distribution in Iran, the Middle East and North Africa. In 1990, by God’s grace, I founded Elam Ministries with a goal to strengthen and expand the church in the Iran region and beyond. One of the primary ways of outreach has been through Scripture translation, production and distribution. Elam has published nearly 1 million Scriptures in Persian during these 21 years. I understand that you are discussing the issue of the ‘Insider Movement’ (IM) at your event, and I am writing this letter to express my serious reservations regarding this subject, particularly with regard to the altering of words in Muslim friendly Bible translations. I have spoken with many Iranian church leaders and I have not found one that is sympathetic to the movement. In the following paragraphs I would like to outline some of our concerns. The Authority of the Word of God: • God’s Word cannot be changed. It is deeply shocking to Iranian Christians that some feel they have the liberty to change God’s Word in order to make the Gospel more palatable to Muslims. Our methods must never compromise the inspired Word that has been passed down to us. -

Theology, Mission and Child: Global Perspectives William Prevette University of Edinburgh, Ir [email protected]

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Edinburgh Centenary Series Resources for Ministry 1-1-2014 Theology, Mission and Child: Global Perspectives William Prevette University of Edinburgh, [email protected] Keith White University of Edinburgh, [email protected] C. Rosalee Velloso da Silva University of Edinburgh, [email protected] D. J. Konz University of Edinburgh, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.csl.edu/edinburghcentenary Part of the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Prevette, William; White, Keith; da Silva, C. Rosalee Velloso; and Konz, D. J., "Theology, Mission and Child: Global Perspectives" (2014). Edinburgh Centenary Series. Book 24. http://scholar.csl.edu/edinburghcentenary/24 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Resources for Ministry at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Edinburgh Centenary Series by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REGNUM EDINBURGH CENTENARY SERIES Volume 24 Theology, Mission and Child: Global Perspectives REGNUM EDINBURGH CENTENARY SERIES The centenary of the World Missionary Conference of 1910, held in Edinburgh, was a suggestive moment for many people seeking direction for Christian mission in the 21st century. Several different constituencies within world Christianity held significant events around 2010. From 2005, an international group worked collaboratively to develop an intercontinental and multi- denominational project, known as Edinburgh 2010, based at New College, University of Edinburgh. This initiative brought together representatives of twenty different global Christian bodies, representing all major Christian denominations and confessions, and many different strands of mission and church life, to mark the centenary. -

A Collective Response to Understanding Insider Movements Eight Southern Baptist Missiologists

The Five Pillars of the Insiders: A Collective Response to Understanding Insider Movements Eight Southern Baptist missiologists (six in the United States and two elsewhere) join forces here to respond briefly to a new volume on Insider Movements (IMs).1 It is an initiative most of us had no intention of taking as little as three months ago, but feel compelled to take now. Quite frankly, some of us were surprised when we received a copy of the book in September 2015. We had rejoiced to see the movement of God as the gospel crossed all kinds of anthropological barriers in our changing world. However, that was not the same as endorsing IMs—or all their promoters claim for them. In fact, we believed that cogent arguments of respected evangelical scholars, against disturbing elements of IMs, had relegated them to the periphery of evangelical missions efforts. Unfortunately, we were mistaken. Advocacy for IMs, as exemplified in the book at hand, is alive and well. It now appears that a major task lies before us. What we present here is simply a preliminary effort which we hope to supplement in months to come. It consists of an overview of the volume, five reflections of a biblical and theological nature, and two missiological insights. It is by no means the last word on the subject. However, as we offer this very limited response to some of the specifics in Understanding Insider Movements, we hope the reader will understand why we are concerned. Ant B. Greenham Ayman S. Ibrahim An Overview of Understanding Insider Movements—and its Five “Pillars”2 The long-awaited volume Understanding Insider Movements has finally been released. -

Carey in Brief Carey's Bengal Legacy Facing a Task Unfinished

8 Friday, July 15, 2011 | THE BAPTIST TIMES THE BAPTIST TIMES | Friday, July 15, 2011 9 Feature Feature he had to get the gospel into a version the people could Facing a task understand. So he set about translating the entire Bible into local languages – from scratch! remarkably, he produced the first Bengali Bible, eventually translating the whole Bible into six languages. William Carey: 250 unfinished he also translated at least one book of the scriptures into another 29, many of which had never been printed before, becoming in the process one of the greatest linguists of all Carey’s story is remarkable, time. that principle of making the gospel known in local languages was key to his success. writes Mark Craig – but Just for good measure, he also developed his interest in botany, studying and cataloguing the local flora and fauna, there’s work still to be done and developing a reputation for excellence in this field which is still intact today. years of mission Edmund and elizabeth Carey’s first child was born in More than 200 years later, the Baptist Missionary 1761, in the tiny Northamptonshire village of Paulerspury. Society continues, under the name BMS World Mission. At the time, there was no reason to suppose that the child, Mission work in India via BMS also continues, with a new William, would go on to change the world. mission boat having been launched last year, to enable local raised in the Church of england, he’d been able to go partners to reach remote villages in the Sunderbans region to school, where he’d shown an early interest in languages. -

Dalit Theology and Indian Christian History in Dialogue: Constructive and Practical Possibilities

religions Article Dalit Theology and Indian Christian History in Dialogue: Constructive and Practical Possibilities Andrew Ronnevik Department of Religion, Baylor University, Waco, TX 76706, USA; [email protected] Abstract: In this article, I consider how an integration of Dalit theology and Indian Christian history could help Dalit theologians in their efforts to connect more deeply with the lived realities of today’s Dalit Christians. Drawing from the foundational work of such scholars as James Massey and John C. B. Webster, I argue for and begin a deeper and more comprehensive Dalit reading and theological analysis of the history of Christianity and mission in India. My explorations—touching on India’s Thomas/Syrian, Catholic, Protestant, and Pentecostal traditions—reveal the persistence and complexity of caste oppression throughout Christian history in India, and they simultaneously draw attention to over-looked, empowering, and liberative resources that are bound to Dalit Christians lives, both past and present. More broadly, I suggest that historians and theologians in a variety of contexts—not just in India—can benefit from blurring the lines between their disciplines. Keywords: Dalit theology; history of Indian Christianity; caste; liberation 1. Introduction In the early 1980s, Christian scholars in India began to articulate a new form of Citation: Ronnevik, Andrew. 2021. theology, one tethered to the lives of a particular group of Indian people. Related to libera- Dalit Theology and Indian Christian tion theology, postcolonialism, and Subaltern Studies, Dalit theology concentrates on the History in Dialogue: Constructive voices, experiences, and aspirations of India’s so-called “untouchables”, who constitute the and Practical Possibilities. -

INDIA Shadow Report

INDIA Shadow Report To the Third and Fourth Combined Report on the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child Submitted by CRC 20 BS Collective July 2012 Published by HAQ: Centre for Child Rights July 2011 Report by: CRC 20 BS collective C/O HAQ: Centre for Child Rights B1/2 Malviya Nagar New Delhi -110017 India Telephone: 91-11-26677412 Fax: 91-11- 26674688 Email: [email protected] Website: www.haqcrc.org Supported by: terre des hommes Germany 1 Preface Government of India submitted its Third and Fourth Combined Report on the Convention on the Rights of the Child to the Committee on the Rights of the Child in 2011, which the Committee is scheduled to consider in its 66th pre-sessional working group to be held in Geneva from 7-11 October 2013. This report by the CRC20BS (Balance Sheet) Collective, is being submitted as an alternative to that submitted by the Government. The CRC 20 BS collective (consisting of 173 organizations and 215 children associated with them) came together to undertake a review of the two decades of implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. It came out with a three volume report titled Twenty Years of CRC- A Balance Sheet in 2011. The process of pulling together the Balance Sheet through consultations with NGOs and children was undertaken by HAQ: Centre for Child Rights Delhi, supported by terre des hommes, Germany. The present shadow report is an update of the Balance Sheet of 2011 (already sent to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child). -

A Humble Appeal to C5/Insider Movement Muslim Ministry

The Jerusalem Council Applied A Humble Appeal to C5/Insider Movement Muslim Ministry Advocates to Consider Ten Questions by Gary Corwin with responses from Brother Yusuf, Rick Brown, Kevin Higgins, Rebecca Lewis and John Travis Gary Corwin: Introductory Comments s a long-time participant in the ISFM, and a long-time reader of and occasional writer for the IJFM, I am exceedingly grateful to A God and to the leaders of both entities for the attention being given to Insider Movements. It is difficult to think of a subject more timely and important as God’s people move forward in the 21st century to make disciples among the least reached peoples of the earth. I have been praying for a number of years now that the kind of dialogue we are having here in Atlanta in these days would soon happen. While it was hap- pening to a limited degree in the pages of both EMQ and the IJFM, neither has been adequate to provide the kind of give and take that a face-to-face gath- ering with a broad representation of views can provide. I was also concerned that C5/IM (Insider Movement) advocates seemed to be traveling the world to talk to one another or to influence the uninitiated, but were not engaging as broadly as needed with their peers in the larger mission community. On a personal level, over the last several years I have serendipitously enjoyed several hours each with a couple of the leading advocates of C5/Insider Movements among Muslims. While helpful in deepening understanding of concerns both for and against, these meetings only increased my sense of need for a broader discussion that was both thoughtful and thorough. -

6427 Hon. Edolphus Towns

May 2, 2000 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 6427 health professionals—the 2 million+ registered In Haryana on April 22, three nuns were at- states like Uttar Pradesh where there have nurses in the United States. tacked by a Hindu fundamentalist. One, Sister been three violent attacks against Christians These outstanding men and women, who Anandi, remains in Holy Family Hospital in se- in the last two weeks. work hard to save lives and maintain the rious condition. No one has been arrested for Madhavrao Scindia, deputy leader of the Congress Party in the Lok Sabha (the lower health of millions of individuals, will celebrate this crime. house of Parliament), said the government National Nurses Week from May 6–12, 2000. The militant Hindu fundamentalists who car- should put a stop to incidents like those re- Registered nurses will be honored by hosting ried out these acts are allies of the Indian gov- ported in Uttar Pradesh and Haryana this or participating in several events such as ral- ernment. The government itself has killed over month. He demanded a response from Home lies, childhood immunizations, community 200,000 Christians in Nagaland, over a quar- Affairs Minister Lal Kishen Advani, who is health screenings, publicity efforts, dinners, re- ter of a million Sikhs, more than 65,000 Kash- considered a friend of most of India’s Hindu ceptions and hospital events. I believe that miri Muslims since 1988, and tens of thou- nationlist groups and is the second most any American who has ever been cared for by sands of others. It holds tens of thousands of powerful man in India after Vajpayee. -

Who W Rote About Sati Name Of

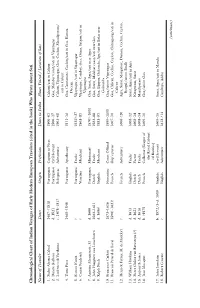

Chronological Chart of Indian Voyages of Early Modern European Travelers (cited in the book) Who Wrote about Sati Name of Traveler Dates Origin Profession Dates in India Places Visited / Location of Sati 1. Pedro Alvares Cabral 1467–?1518 Portuguese Captain of Fleet 1500–01 Calicut/sati in Calicut 2. Duarte Barbosa d. 1521 Portuguese Civil Servant 1500–17 Goa, Malabar Coast/sati in Vijaynagar 3. Ludovico di Varthema c. 1475–1517 Bolognese Adventurer 1503–08 Calicut, Vijaynagar, Goa, Cochin, Masulipatam/ sati in Calicut 4. Tome Pires 1468–1540 Portuguese Apothecary 1511–16 Goa, Cannanore, Cochin/sati in Goa, Kanara, Deccan 5. Fernao Nuniz ? Portuguese Trader 1535?–37 Vijaynagar/sati in Vijaynagar 6. Caesar Frederick ? Venetian Merchant 1563–81 Vijaynagar, Cambay, Goa, Orissa, Satgan/sati in Vijaynagar 7. Antoine Monserrate, SJ d. 1600 Portuguese Missionary 1570?–1600 Goa, Surat, Agra/sati near Agra 8. John Huyghen van Linschoten 1563–1611 Dutch Trader 1583–88 Goa, Surat, Malabar coast/sati near Goa 9. Ralph Fitch d. 1606? English Merchant 1583–91 Goa, Bijapur, Golconda, Agr/sati in Bidar near Golconda 10. Francesco Carletti 1573–1636 Florentine Court Official 1599–1601 Goa/sati in Vijaynagar 11. Francois Pyrard de Laval 1590?–1621? French Ship’s purser 1607–10 Goa, Calicut, Cochin, Ceylon, Chittagong/sati in Calicut 12. Henri de Feynes, M. de Montfort ? French Adventurer 1608–?20 Agra, Surat, Mangalore, Daman, Cochin, Ceylon, Bengal/sati in Sindh 13. William Hawkins d. 1613 English Trader 1608–12 Surat, Agra/sati in Agra 14. Pieter Gielisz van Ravesteyn (?) d. 1621 Dutch Factor 1608–14 Nizapatam, Surat 15. -

Download Release 15

BIBLICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE Gordon E. Christo RELEASE15 The History of the Seventh-day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists Gordon E. Christo Biblical Research Institute Silver Spring, Maryland Copyright © 2020 by the Biblical Research Institute Silver Spring, Maryland www.adventistbiblicalresearch.org General editor: Ekkehardt Mueller Editor: Clinton Wahlen Managing editor: Marly Timm Editorial assistance and layout: Patrick V. Ferreira Copy editor: Schuyler Kline Author: Christo, Gordon Title: Te History of the Seventh-day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists Subjects: Sabbath - India Sabbatarians - India Call Number: V125.S32 2020 Printed in the U.S.A. ISBN 978-0-925675-42-2 Contents Introduction ............................................................................... 1 Early Presence of Jews in India ............................................. 3 Bene Israel ............................................................................. 3 Cochin Jews ........................................................................... 4 Early Christianity in India ....................................................... 6 Te Report of Pantaneus ................................................... 7 “Te Doctrine of the Apostles” ........................................ 8 Te Acts of Tomas ........................................................... 8 Traditions of the Tomas Christians ............................... 9 Tomas Christians and the Sabbath ....................................... 10