Colonialism and After: a Study of Select Fictional Echoes from India and Africa Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Affairs

Mahendra Publication CONTENTS Pvt. Ltd. VOL-13 ISSUE -05 Editor Success Saga 5 N.K. Jain IBPS 6-9 Advisors Spotlight 10 Neeraj Chabra The People 12-22 K.C.Gupta News Bytes 24-84 Minister of Railways Flags off Country’s first Antyodaya Registered Office Express running between Ernakulam - Howrah 85-87 Mahendra Publication Pvt. Ltd. Swachh Bharat Milestone- 100 districts in India declared ODF 88 103, Pragatideep Building, Shri Kiren Rijiju launches “MySSB APP” 89 Plot No. 08, Laxminagar, President of India inaugurates international conference on ‘Bharat Bodh’ 90 District Centre, New Delhi - 110092 Lok Sabha passes the Enemy Property Bill 2016 91 TIN-09350038898 29th Academy Awards 2017 92-93 w.e.f. 12-06-2014 Que Tm - General Awareness 95-100 NP QUIZ 102-104 Branch Office Graphic Factory 106-112 Mahendra Publication Pvt. Ltd. Who’s Who 113 E-42,43,44, Sector-7, Noida (U.P.) For queries regarding ANTYODAYA EXPRESS promotion, distribution & advertisement, contact:- [email protected] Ph.: +91-9670575613 SWACHH BHARAT MILESTONE Owned, printed & published by N.K. Jain 103, Pragatideep Building, SHRI KIREN RIJIJU LAUNCHES “MYSSB APP” Plot No. 08, Laxminagar, District Centre, New Delhi - 110092 Please send your suggestions and grievances to:- ‘BHARAT BODH’ Mahendra Publication Pvt. Ltd. CP-9, Vijayant Khand, Gomti Nagar Lucknow - 226010 E-mail:[email protected] LOK SABHA PASSES THE ENEMY © Copyright Reserved PROPERTY BILL 2016 # No part of this issue can be printed in whole or in part without the written permission of the publishers. # All the disputes are subject to Delhi 29TH ACADEMY AWARDS 2017 jurisdiction only. -

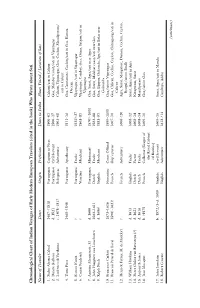

Who W Rote About Sati Name Of

Chronological Chart of Indian Voyages of Early Modern European Travelers (cited in the book) Who Wrote about Sati Name of Traveler Dates Origin Profession Dates in India Places Visited / Location of Sati 1. Pedro Alvares Cabral 1467–?1518 Portuguese Captain of Fleet 1500–01 Calicut/sati in Calicut 2. Duarte Barbosa d. 1521 Portuguese Civil Servant 1500–17 Goa, Malabar Coast/sati in Vijaynagar 3. Ludovico di Varthema c. 1475–1517 Bolognese Adventurer 1503–08 Calicut, Vijaynagar, Goa, Cochin, Masulipatam/ sati in Calicut 4. Tome Pires 1468–1540 Portuguese Apothecary 1511–16 Goa, Cannanore, Cochin/sati in Goa, Kanara, Deccan 5. Fernao Nuniz ? Portuguese Trader 1535?–37 Vijaynagar/sati in Vijaynagar 6. Caesar Frederick ? Venetian Merchant 1563–81 Vijaynagar, Cambay, Goa, Orissa, Satgan/sati in Vijaynagar 7. Antoine Monserrate, SJ d. 1600 Portuguese Missionary 1570?–1600 Goa, Surat, Agra/sati near Agra 8. John Huyghen van Linschoten 1563–1611 Dutch Trader 1583–88 Goa, Surat, Malabar coast/sati near Goa 9. Ralph Fitch d. 1606? English Merchant 1583–91 Goa, Bijapur, Golconda, Agr/sati in Bidar near Golconda 10. Francesco Carletti 1573–1636 Florentine Court Official 1599–1601 Goa/sati in Vijaynagar 11. Francois Pyrard de Laval 1590?–1621? French Ship’s purser 1607–10 Goa, Calicut, Cochin, Ceylon, Chittagong/sati in Calicut 12. Henri de Feynes, M. de Montfort ? French Adventurer 1608–?20 Agra, Surat, Mangalore, Daman, Cochin, Ceylon, Bengal/sati in Sindh 13. William Hawkins d. 1613 English Trader 1608–12 Surat, Agra/sati in Agra 14. Pieter Gielisz van Ravesteyn (?) d. 1621 Dutch Factor 1608–14 Nizapatam, Surat 15. -

Download Release 15

BIBLICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE Gordon E. Christo RELEASE15 The History of the Seventh-day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists Gordon E. Christo Biblical Research Institute Silver Spring, Maryland Copyright © 2020 by the Biblical Research Institute Silver Spring, Maryland www.adventistbiblicalresearch.org General editor: Ekkehardt Mueller Editor: Clinton Wahlen Managing editor: Marly Timm Editorial assistance and layout: Patrick V. Ferreira Copy editor: Schuyler Kline Author: Christo, Gordon Title: Te History of the Seventh-day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists Subjects: Sabbath - India Sabbatarians - India Call Number: V125.S32 2020 Printed in the U.S.A. ISBN 978-0-925675-42-2 Contents Introduction ............................................................................... 1 Early Presence of Jews in India ............................................. 3 Bene Israel ............................................................................. 3 Cochin Jews ........................................................................... 4 Early Christianity in India ....................................................... 6 Te Report of Pantaneus ................................................... 7 “Te Doctrine of the Apostles” ........................................ 8 Te Acts of Tomas ........................................................... 8 Traditions of the Tomas Christians ............................... 9 Tomas Christians and the Sabbath ....................................... 10 -

Conversion in the Pluralistic Religious Context of India: a Missiological Study

Conversion in the pluralistic religious context of India: a Missiological study Rev Joel Thattupurakal Mathai BTh, BD, MTh 0000-0001-6197-8748 Thesis submitted for the degree Philosophiae Doctor in Missiology at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University in co-operation with Greenwich School of Theology Promoter: Dr TG Curtis Co-Promoter: Dr JJF Kruger April 2017 Abstract Conversion to Christianity has become a very controversial issue in the current religious and political debate in India. This is due to the foreign image of the church and to its past colonial nexus. In addition, the evangelistic effort of different church traditions based on particular view of conversion, which is the product of its different historical periods shaped by peculiar constellation of events and creeds and therefore not absolute- has become a stumbling block to the church‘s mission as one view of conversion is argued against the another view of conversion in an attempt to show what constitutes real conversion. This results in competitions, cultural obliteration and kaum (closed) mentality of the church. Therefore, the purpose of the dissertation is to show a common biblical understanding of conversion which could serve as a basis for the discourse on the nature of the Indian church and its place in society, as well as the renewal of church life in contemporary India by taking into consideration the missiological challenges (religious pluralism, contextualization, syncretism and cultural challenges) that the church in India is facing in the context of conversion. The dissertation arrives at a theological understanding of conversion in the Indian context and its discussion includes: the multiple religious belonging of Hindu Christians; the dual identity of Hindu Christians; the meaning of baptism and the issue of church membership in Indian context. -

Download Individual TIFF Images for Personal Use

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title From Inquisition to E-Inquisition: A Survey of Online Sources on the Portuguese Inquisition Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05k4h9qb Journal Journal of Lusophone Studies, 4(2) ISSN 2469-4800 Author Pendse, Liladhar Publication Date 2020 DOI 10.21471/jls.v4i2.241 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California From Inquisition to E-Inquisition: A Survey of Online Sources on the Portuguese Inquisition LILADHAR R. PENDSE University of California, Berkeley Abstract: The Portuguese Inquisition in the colonies of the Empire remains understudied due to a lack of primary source materials that are available the researchers and educators. The advances in digital technologies and the current drive to foster Open Access have allowed us to understand better the relations among the complex set of circumstances as well as the mechanisms that, in their totality, represent the Portuguese Inquisition. The present paper seeks to answer questions that vary from describing these resources to identifying the institutions that created them. Digitized resources serve as a surrogate of the originals, and we can leverage the access to these electronic surrogates and enhance our understanding of the mechanisms of inquisition through E-Inquisitional objects in pedagogy and research. Keywords: Empire, Brazil, India, Africa, archives, open access The study of the history of the Portuguese Inquisition and its institutions has acquired importance in the context of early efforts to convert, indoctrinate, organize and “civilize” the large native and indigenous populations over the vast global expanse of the Portuguese Empire. From the beginning, the Portuguese Crown formed an alliance with the Catholic Church to promote proselytization in its early colonial acquisitions in India. -

Previous Year GK Questions Free Static GK E-Book

PREVIOUS YEAR IMPORTANT GK QUESTIONS For SSC CGL Examination Previous Year GK Questions Free static GK e-book General Knowledge is very important for SSC CGL examination. Aspirants preparing for SSC CGL examination should be aware of all the important General Knowledge questions that can be asked in the examination. Keeping in mind the same we have brought you a free e-book on SSC CGL Previous Year GK questions. Download the Part 1 of free PDF, we will be coming up with more e-books that will help you in upcoming SSC CGL examination. Previous Year GK Questions Free static GK e-book SSC CGL PREVIOUS YEAR GK QUESTIONS Q1) Sundari, a well-known species of trees, is found in? A. TROPICAL RAINFORESTS B. HIMALAYAN MOUNTAINS C. TROPICAL DECIDUOUS FORESTS D. MANGROVE FORESTS Correct Answer: “D” Q2) Methyl propane is an isomer of? A. n-hexane B. n-butane C. n-propane D. n-pentane Correct Answer: “B” Q3) Which queen died fighting Mughal armies while defending Garha Katanga in 1564? A. RANI AVANTIBAI B. RANI RUDRAMBARA C. RANI DURGAVATI D. RANI AHILYABAI Correct Answer: “C” Q4) Rihand Dam Project provides irrigation to A. GUJARAT AND MAHARASHTRA B. ODISHA AND WEST BENGAL C. UTTAR PRADESH AND BIHAR D. KERALA AND KARNATAKA Correct Answer: “C” Q5) The Headquarters of MCF (Master Control Facility) – the nerve centre of all entire space craft operations-in India is at A. HYDERABAD – TELANGANA B. THUMBA – KERALA C. SRIHARIKOTA –ANDHRA PRADESH D. HASSAN – KARNATAKA Correct Answer: “D” Previous Year GK Questions Free static GK e-book Q6) Which is the longest irrigation canal in India? A. -

1 Wifistudy.Com

• Currency: Dollar • Prime Minister: Malcolm Turnbull By 2050, India will have most Muslims in world Ukraine region to use Russian ruble as currency By 2050, India will be the Ukraine's self-proclaimed Luhansk People's Republic will use country with the world's the Russian ruble as its official currency, according to an largest Muslim population, official statement. said American think tank The ruble would be used in the pro-Russian territory as the Pew Research Centre. basic unit of currency as of 1 March 2017, the statement While Islam is said. currently the world's The use of the ruble, which is already used informally in second-largest religion after Christianity, it is now also the the pro-Russian territory along with the Ukrainian hryvnia, fastest-growing major religion. serves to stabilise the volatile economic situation in the There were 1.6 billion Muslims in the world as of 2010 - region. roughly 23% of the global population - according to a Pew Ukraine estimate. Currently, Indonesia has the world's largest Muslim • Capital: Kiev population. • Currency: Hryvnia • Prime Minister: Volodymyr Groysman Syrian Army recaptures Palmyra from Islamic State • President: Petro Poroshenko The General Staff of the Syrian Army said it had recaptured the ancient city of Palmyra from the extremist group Islamic State Pakistan hosted 13th ECO Summit in Islamabad (IS). The 13th Economic Cooperation Organisation Summit was The city, which is home to Greco-Roman ruins on the held in Islamabad, Pakistan. United Nations cultural body’s World Heritage list, had The theme of ECO Summit was "Connectivity for been the scene of heavy fighting for months. -

Day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-Day Adventists

The History of the Seventh- day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists Biblical Research Institute Release – 15 Gordon E. Christo The History of the Seventh- day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists Gordon E. Christo Biblical Research Institute Silver Spring, Maryland Copyright © 2020 by the Biblical Research Institute Silver Spring, Maryland www.adventistbiblicalresearch.org General editor: Ekkehardt Mueller Editor: Clinton Wahlen Managing editor: Marly Timm Editorial assistance and layout: Patrick V. Ferreira Copy editor: Schuyler Kline Author: Christo, Gordon Title: Te History of the Seventh-day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists Subjects: Sabbath - India Sabbatarians - India Call Number: V125.S32 2020 Printed in the U.S.A. by the Pacifc Press Publishing Association Nampa, ID 83653-5353 ISBN 978-0-925675-42-2 Contents Introduction ............................................................................... 1 Early Presence of Jews in India ............................................. 3 Bene Israel ............................................................................. 3 Cochin Jews ........................................................................... 4 Early Christianity in India ....................................................... 6 Te Report of Pantaneus ................................................... 7 “Te Doctrine of the Apostles” ........................................ 8 Te Acts of Tomas .......................................................... -

Festival of Letters 2014

DELHI Festival of Letters 2014 Conglemeration of Writers Festival of Letters 2014 (Sahityotsav) was organised in Delhi on a grand scale from 10-15 March 2014 at a few venues, Meghadoot Theatre Complex, Kamani Auditorium and Rabindra Bhawan lawns and Sahitya Akademi auditorium. It is the only inclusive literary festival in the country that truly represents 24 Indian languages and literature in India. Festival of Letters 2014 sought to reach out to the writers of all age groups across the country. Noteworthy feature of this year was a massive ‘Akademi Exhibition’ with rare collage of photographs and texts depicting the journey of the Akademi in the last 60 years. Felicitation of Sahitya Akademi Fellows was held as a part of the celebration of the jubilee year. The events of the festival included Sahitya Akademi Award Presentation Ceremony, Writers’ Meet, Samvatsar and Foundation Day Lectures, Face to Face programmmes, Live Performances of Artists (Loka: The Many Voices), Purvottari: Northern and North-Eastern Writers’ Meet, Felicitation of Akademi Fellows, Young Poets’ Meet, Bal Sahiti: Spin-A-Tale and a National Seminar on ‘Literary Criticism Today: Text, Trends and Issues’. n exhibition depicting the epochs Adown its journey of 60 years of its establishment organised at Rabindra Bhawan lawns, New Delhi was inaugurated on 10 March 2014. Nabneeta Debsen, a leading Bengali writer inaugurated the exhibition in the presence of Akademi President Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari, veteran Hindi poet, its Vice-President Chandrasekhar Kambar, veteran Kannada writer, the members of the Akademi General Council, the media persons and the writers and readers from Indian literary feternity. -

Regional Language Books

January 2010 Regional Language Books BENGALI 1 Dasgupta, Ananda, ed. Sadhinata: swadesh samaj sanskriti / edited by Ananda Dasgupta.-- Kolkata: Gangchil, 2008. 235p.; 21cm. ISBN : 978-81-89834-39-5. B 080 DAS-s C67553 2 Kallol Prabandha sangraha / Kallol; edited by Barid Baran Ghosh.-- Kolkata: Punashcha, 2006. 576p.; 22cm. ISBN : 81-7332-482-4. B 080 KAL-p C64073 3 Mukhopadhyay, Malay Paribesh bhabna anya chokhey / Malay Mukhopadhyay.-- Kolkata: Deep Prakashan, 2007. 126p.; 21cm. B 080 MUK-p C65815 4 Sarkar, Motilal Dwandwa O bikash / Motilal Sarkar.--2nd ed.-- Agartala: Bibhutibhushan Saharoy, 2009. 76p.; 21cm. B 080 SAR-d C67527 5 Sarkar, Motilal Prabaha / Motilal Sarkar.-- Agartala: Bibhutibhushan Saharoy, 1999. 2v.; 21cm. B 080 SAR-p C67529 - C67530,V.1 - V.2 6 Bhattacharjee, Debobrata Bharatiya, lokojivan-o-sahityee dainivrittir prabhav-o- prasar / Debobrata Bhattacharjee.-- Kolkata: Punascho, 2008. 200p.; 21cm. ISBN : 81-978-7332-545-8. B 133.430954 P8 C67550 7 Sen, Khitimohan Hindudharma / Khitimohan Sen; translated by Somendranath Bandyopadhyay.-- Kolkata: Ananda Publishers, 2008. 161p.; 21cm. ISBN : 81-7756-678-4. B 294.5 P8 C67555 8 Bhattacharya, Shyamadas Shillonger Bangali: Shillonge Bangali avadan O bartaman / Shyamadas Bhattacharya.-- Kolkata: Angel Udyog, 2007. 285p.; 22cm. B 305.744054212 P7 C66582 9 Chakravarti, Barun Kumar, ed. Oitijjher prekshapate bangajiban / edited by Barun Kumar Chakraborty...[et al].-- Kolkata: Pustak Bipani, 2005. 592p.; 21cm. B 305.89144 P5 C63916 10 Sarkar, Motilal Jiban o sanskriti / Motilal Sarkar.-- Agartala: Bibhutibhushan Saharoy, 2009. 35p.; 21cm. B 306.095423 P9 C67528 11 Majumdar, Dibyajyoti Adibasi lokokatha / Dibyajyoti Majumdar.--2nd ed.-- Kolkata: Ekushshatak, 2007. 358p.; 21cm. B 398.21095423 P7 C67453 12 Roy, Binoy Bhushan Chikitsabijnaner itihas / Binoy Bhushan Roy.-- Kolkata: Sahitya Lok, 2005. -

Unique Ias Academy March 2017 English Current Affairs

UNIQUE IAS ACADEMY MARCH 2017 ENGLISH CURRENT AFFAIRS March 1, 2017 4th India-CLMV Business Conclave held in Jaipur 01-Mar-17 The fourth edition of India – CLMV (Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar and Vietnam) Business Conclave was held in Jaipur, capital of Rajasthan. The two-day conference organised by Department of Commerce and Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) held deliberations on manufacturing, renewable energy, agriculture and skilling among others sectors in the region. About World Health Organization (WHO) WHO is a specialized agency of the UN that is concerned with international public health. It was established in April 1948. It is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland. It is member of the United Nations Development Group. It is responsible for the World Health Report, a leading international publication on health, the worldwide World Health Survey MEITY to promote digital transactions in place of NITI Aayog 01-Mar-17 The Union Government has shifted the responsibility of promoting digital transactions in the country to the Union Ministry of IT and Electronics (MEITY) from NITI (National Institution for Transforming India) Aayog the Government. Madras HC orders TN Government to enact law to remove Seemai Karuvelam trees 01-Mar-17 The Madurai bench of the Madras High Court has ordered Tamil Nadu government to enact a law with prohibitory and penal clauses to eradicate Seemai Karuvelam (prosopis juliflora) trees within two months the Government. About Seemai Karuvelam tree Seemai Karuvelam tree species are native to West Africa. -

Knight of the Renaissance: D

THE NEW CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF INDIA The Portuguese in India Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008 THE NEW CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF INDIA General editor GORDON JOHNSON Director, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of Selwyn College Associate editors C. A. BAYLY Smuts Reader in Commonwealth Studies, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of St Catharine's College and JOHN F. RICHARDS Professor of History, Duke University Although the original Cambridge History of India, published between 1922 and 1937, did much to formulate a chronology for Indian history and de- scribe the administrative structures of government in India, it has inevitably been overtaken by the mass of new research published over the last fifty years. Designed to take full account of recent scholarship and changing concep- tions of South Asia's historical development, The New Cambridge History of India will be published as a series of short, self-contained volumes, each dealing with a separate theme and written by a single person. Within an overall four-part structure, thirty complementary volumes in uniform format will be published during the next five years. As before, each will conclude with a substantial bibliographical essay designed to lead non-specialists further into the literature. The four parts planned are as follows: I The Mughals and their Contemporaries. II Indian States and the Transition to Colonialism. Ill The Indian Empire and the Beginnings of Modern Society. IV The Evolution of Contemporary South Asia. A list of individual titles in preparation will be found at the end of the volume. Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008 Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008 Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008 THE NEW CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF INDIA I • 1 The Portuguese in India M.