Day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-Day Adventists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Thomas the Apostle Parish

St. Thomas the Apostle Parish Diocese of Peoria 904 E Lake Ave Peoria Heights stthomaspeoria.org St Thomas the Apostle Church TWENTIETH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME Peoria Heights, Illinois August 20, 2017 TWENTIETH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME Reading I: Isaiah 56:1,6-7 Reading II: Romans 11:13-15,29-32 Gospel: Matthew 15:21-28 In today’s world the conversation about differences is loud and bold. Differences create wedges at times; differences THAT MAN IS YOU REGISTRATION will be after make for enrichment of the whole at times. Jesus even Masses on Aug 19/20 and Aug 26/27 seems in the Gospel today to draw lines about who is “in” and “out.” But a critical conclusion to the story places ST THOMAS SCHOOL MEET & GREET Sunday, Aug 20 Jesus’ teaching square in the center. He cures the daughter from 8:30 am to 12:30 pm in the school of the woman who was an outsider because she believed in who Jesus was and what He could do. She had faith in CENTERING PRAYER Monday, Aug 21 at 8:30 am in Him beyond that of the people who were around Jesus. the old church basement Being open enough to see the other as good and willing to put trust in Jesus is a message that today’s world needs. FIRST DAY OF SCHOOL Monday, Aug 21 with All Do we trust that Jesus can and will do what He says? School Mass at 9:15 am and dismissal at 12:15 pm ROSARY FOR PEACE Tuesday, Aug 22 at 10:00 am in the chapel Monday, August 21, 2017-St Pius X 7:00am Benefactors of Franciscan Sisters of St John the NO BIBLE STUDY Wednesday, Aug 23 at 8:45 am in Baptist the parish office meeting room 8:00am Rick Bastonero/Lucille Harczuk & Family 9:15pm Anthony Arnold/The Arnold Family CHARISMATIC PRAYER GROUP Thursday, Aug 24 at Tuesday, August 22, 2017-The Queenship of the Blessed 7:00 pm in the old church basement Virgin Mary 7:00am Amanda Burtsfield Kent/Family BACK-TO-SCHOOL NIGHT PRE-3 THROUGH GRADE 1 8:00am Dan Van Buskirk/Family Thursday, Aug 24 at 7:00 pm in the school gym;. -

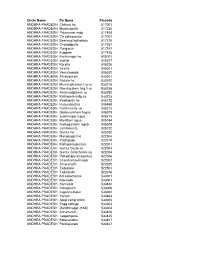

Post Offices

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

The Church Missionary Society and the Christians of Kerala, 1813-1840

Half-Brothers in Christ: The Church Missionary Society and the Christians of Kerala, 1813-1840 by Joseph Gerald Howard M. A. (History), University at Buffalo, State University of New York, 2010 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Joseph Gerald Howard 2014 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2014 Approval Name: Joseph Gerald Howard Degree: Master of Arts (History) Title: Half-Brothers in Christ: The Church Missionary Society and the Christians of Kerala, 1813-1840 Examining Committee: Chair: Aaron Windel Assistant Professor of History Paul Sedra Senior Supervisor Associate Professor of History Derryl MacLean Supervisor Associate Professor of History Mary-Ellen Kelm Supervisor Professor of History Laura Ishiguro External Examiner Assistant Professor Department of History University of British Columbia Date Defended: August 28, 2014 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract In the 1810s, the Church Missionary Society (CMS) established the College at Cottayam in south India to educate boys intended for the priesthood in the local, indigenous church. While their goal was to help the church, their activities increased British power in the community. The results of CMS involvement included increasing interference of British officials in matters internal to the Malankara Church (e.g., episcopal succession), tacit recognition of the authority of colonial courts to resolve disputes in the church, and the fragmentation of the St. Thomas Christian community. These effects reshaped the church into something more consistent with British Christianity and more subject to British rule. Keywords: British Empire; Christianity; India; mission iv Dedication In memory of M. -

Unit 17 Christian Social Organisation

Social Organisation UNIT 17 CHRISTIAN SOCIAL ORGANISATION Structure 17.0 Objectives 17.1 Introduction 17.2 Origin of Christianity in India 17.2.1 Christian Community: The Spatial and Demographic Dimensions 17.2.2 Christianity in Kerala and Goa 17.2.3 Christianity in the East and North East 17.3 Tenets of Christian Faith 17.3.1 The Life of Jesus 17.3.2 Various Elements of Christian Faith 17.4 The Christians of St. Thomas: An Example of Christian Social Organisation 17.4.1 The Christian Family 17.4.2 The Patrilocal Residence 17.4.3 The Patrilineage 17.4.4 Inheritance 17.5 The Church 17.5.1 The Priest in Christianity 17.5.2 The Christian Church 17.5.3 Christmas 17.6 The Relation of Christianity to Hinduism in Kerala 17.6.1 Calendar and Time 17.6.2 Building of Houses 17.6.3 Elements of Castes in Christianity 17.7 Let Us Sum Up 17.8 Key Words 17.9 Further Reading 17.10 Specimen Answers to Check Your Progress 17.0 OBJECTIVES This unit describes the social organisation of Christians in India. A study of this unit will enable you to z explain the origin of Christianity in India z list and describe the common features of Christian faith z describe the Christian social organisation in terms of family, the role of the priest, church and Christmas among Syrian Christians of Kerala z identify and explain the areas of relationship between Christian and Hindu 42 social life in Kerala. Christian Social 17.1 INTRODUCTION Organisation In the previous unit we have looked at Muslim social organisation. -

Directory 2017

DISTRICT DIRECTORY / PATHANAMTHITTA / 2017 INDEX Kerala RajBhavan……..........…………………………….7 Chief Minister & Ministers………………..........………7-9 Speaker &Deputy Speaker…………………….................9 M.P…………………………………………..............……….10 MLA……………………………………….....................10-11 District Panchayat………….........................................…11 Collectorate………………..........................................11-12 Devaswom Board…………….............................................12 Sabarimala………...............................................…......12-16 Agriculture………….....…...........................……….......16-17 Animal Husbandry……….......………………....................18 Audit……………………………………….............…..…….19 Banks (Commercial)……………..................………...19-21 Block Panchayat……………………………..........……….21 BSNL…………………………………………….........……..21 Civil Supplies……………………………...............……….22 Co-Operation…………………………………..............…..22 Courts………………………………….....................……….22 Culture………………………………........................………24 Dairy Development…………………………..........………24 Defence……………………………………….............…....24 Development Corporations………………………...……24 Drugs Control……………………………………..........…24 Economics&Statistics……………………....................….24 Education……………………………................………25-26 Electrical Inspectorate…………………………...........….26 Employment Exchange…………………………...............26 Excise…………………………………………….............….26 Fire&Rescue Services…………………………........……27 Fisheries………………………………………................….27 Food Safety………………………………............…………27 -

The Life of St. Bartholomew

The Life of St. Bartholomew BARTHOLOMEW, a Galilean, was one of the twelve apostles. His name is most probably not a given name, but a family name. He is listed among the twelve apostles in the three synoptic gospels: Matthew, Mark and Luke. He also appears as one of the witnesses of the Ascension (Acts 1:4, 12, 13). He is generally supposed to be the same person as Nathanael. In the synoptic gospels, Philip and Bartholomew are always mentioned together, while Nathanael is never mentioned; in the gospel of John, on the other hand, Philip and Nathanael are similarly mentioned together, but nothing is said of Bartholomew. Also in John, Nathanael is introduced as a friend of Philip. Eusebius of Caesarea's Ecclesiastical History states that after the Ascension, Bartholomew went on a missionary tour to India, which Jacobus de Voragine, Archbishop of Genoa wrote in 1275, “is the end of the world.” According to legend, he lived in a temple of the idol, Astaroth, and healed people in Jesus' name of all manner of illnesses which the local priests were only able to “make better for a while.” When the sick then went to another temple for healing, they were told that when Bartholomew, the apostle of God, entered the temple, the idol was “bound with chains of fire” which prevented it from acting. Legend says that the devil reported to his followers, “if ye find him, ye pray him that he come not hither, that his angels do not to me as they have done to my fellow.” According to de Voragine, Bartholomew wore the same white coat and white mantle for twenty-six years and “his clothes never waxed old [nor] foul.” He was reported to pray a hundred times by day and a hundred times by night. -

Pathanamthitta

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-A SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA 2 CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Village and Town Directory PATHANAMTHITTA Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala 3 MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. 4 CONTENTS Pages 1. Foreword 7 2. Preface 9 3. Acknowledgements 11 4. History and scope of the District Census Handbook 13 5. Brief history of the district 15 6. Analytical Note 17 Village and Town Directory 105 Brief Note on Village and Town Directory 7. Section I - Village Directory (a) List of Villages merged in towns and outgrowths at 2011 Census (b) -

Chapter I Christianity in Kerala: Tracing Antecedents

CHAPTER I CHRISTIANITY IN KERALA: TRACING ANTECEDENTS Introduction This chapter is an analysis of the early history of Christianity in Kerala. In the initial part it attempts to trace the historical background of Christianity from its origin to the end of seventeenth century. The period up to the colonial period forms the first part after which the history of the colonial part is given. This chapter also tries to examine how colonial forces interfered in the life of Syrian Christians and how it became the foremost factor for the beginning of conflicts. It tried to explain about the splits that happened in the community because of the interference of the Portuguese. It likewise deals with the relation of Dutch with the Syrian Christian community. It also discusses the conflict between the Jesuit and Carmelite missionaries. History of Christianity in Kerala in the Pre-Colonial Period Kerala, which is situated on the south west coast of Peninsular India, is one of the oldest centers of Christianity in the world. This coast was popularly known as Malabar. The presence of Christian community in the pre-colonial period of Kerala is an unchallenged reality. It began to appear here from the early days of Christendom.1 But the exact period in which Christianity was planted in Malabar, by whom, how or under what conditions, cannot be said with any confidence. However historians have offered unimportant guesses in the light of traditional legends and sources. The origin of Christianity was subject to wide enquiry and research by scholars. Different contradictory theories have been formulated by historians, religious leaders, and politicians on the Christian proselytizing in India. -

Is Caste System Prevalent Among the Syrian Christians of Kerala? a Critical Analysis

Vol. 5 No. 3 January 2018 ISSN: 2321-788X UGC Approval No: 43960 Impact Factor: 2.114 IS CASTE SYSTEM PREVALENT AMONG THE SYRIAN CHRISTIANS OF KERALA? A CRITICAL ANALYSIS THOMAS P JOHN Assistant Professor in History St. Xavier’s College, Thumba, Kerala, India Article Particulars: Received: 25.11.2017 Accepted: 06.12.2017 Published: 20.01.2018 Abstract The concept of caste has ever been a reality in all societies and countries, and yet there exists some ambiguities in understanding the concept of caste in some communities. A great confusion exists among the academicians as well as in the general public about the concept of caste in the Syrian Christian community in Kerala. The multiplicity of denominations among them, each having their own Rite, Liturgy, Clergy, Ecclesial hierarchy etc. had created great confusion among the people especially among the non Christians. Vague ideas had taken position and a majority including learned historians and thinkers are totally mistaken in this regard. Some interpret these varieties as separate castes. Hence, an earnest attempt to find out the truth in this matter is urgent. This article is an attempt to deactivate the wrong concepts about the caste factor in the Syrian Christian community and to replace it with the most reasonable and genuine knowledge of the same. It finds out that all the different Syrian Christian groups except the ‘Knanites’ forms one single cast and the difference is only denominational. Keywords: Caste, Religion, Syrian Christians, St. Thomas Tradition, Synod of Diamper, Coonnan Cross Oath, ‘Mission of Help’ Malankara, Jacobite, Knanaya, Marthoma Syrian, Pazhayakooru, Puthenkooru, Idavaka. -

The Pneumatic Experiences of the Indian Neocharismatics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE PNEUMATIC EXPERIENCES OF THE INDIAN NEOCHARISMATICS By JOY T. SAMUEL A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham June 2018 i University of Birmingham Research e-thesis repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and /or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any success or legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. i The Abstract of the Thesis This thesis elucidates the Spirit practices of Neocharismatic movements in India. Ever since the appearance of Charismatic movements, the Spirit theology has developed as a distinct kind of popular theology. The Neocharismatic movement in India developed within the last twenty years recapitulates Pentecostal nature spirituality with contextual applications. Pentecostalism has broadened itself accommodating all churches as widely diverse as healing emphasized, prosperity oriented free independent churches. Therefore, this study aims to analyse the Neocharismatic churches in Kerala, India; its relationship to Indian Pentecostalism and compares the Sprit practices. It is argued that the pneumatology practiced by the Neocharismatics in Kerala, is closely connected to the spirituality experienced by the Indian Pentecostals. -

Catholic Shrines in Chennai, India: the Politics of Renewal and Apostolic Legacy

CATHOLIC SHRINES IN CHENNAI, INDIA: THE POLITICS OF RENEWAL AND APOSTOLIC LEGACY BY THOMAS CHARLES NAGY A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Religious Studies Victoria University of Wellington (2014) Abstract This thesis investigates the phenomenon of Catholic renewal in India by focussing on various Roman Catholic churches and shrines located in Chennai, a large city in South India where activities concerning saintal revival and shrinal development have taken place in the recent past. The thesis tracks the changing local significance of St. Thomas the Apostle, who according to local legend, was martyred and buried in Chennai. In particular, it details the efforts of the Church hierarchy in Chennai to bring about a revival of devotion to St. Thomas. In doing this, it covers a wide range of issues pertinent to the study of contemporary Indian Christianity, such as Indian Catholic identity, Indian Christian indigeneity and Hindu nationalism, as well as the marketing of St. Thomas and Catholicism within South India. The thesis argues that the Roman Catholic renewal and ―revival‖ of St. Thomas in Chennai is largely a Church-driven hierarchal movement that was specifically initiated for the purpose of Catholic evangelization and missionization in India. Furthermore, it is clear that the local Church‘s strategy of shrinal development and marketing encompasses Catholic parishes and shrines throughout Chennai‘s metropolitan area, and thus, is not just limited to those sites associated with St. Thomas‘s Apostolic legacy. i Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my father Richard M. -

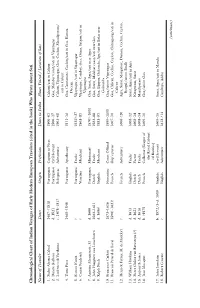

Who W Rote About Sati Name Of

Chronological Chart of Indian Voyages of Early Modern European Travelers (cited in the book) Who Wrote about Sati Name of Traveler Dates Origin Profession Dates in India Places Visited / Location of Sati 1. Pedro Alvares Cabral 1467–?1518 Portuguese Captain of Fleet 1500–01 Calicut/sati in Calicut 2. Duarte Barbosa d. 1521 Portuguese Civil Servant 1500–17 Goa, Malabar Coast/sati in Vijaynagar 3. Ludovico di Varthema c. 1475–1517 Bolognese Adventurer 1503–08 Calicut, Vijaynagar, Goa, Cochin, Masulipatam/ sati in Calicut 4. Tome Pires 1468–1540 Portuguese Apothecary 1511–16 Goa, Cannanore, Cochin/sati in Goa, Kanara, Deccan 5. Fernao Nuniz ? Portuguese Trader 1535?–37 Vijaynagar/sati in Vijaynagar 6. Caesar Frederick ? Venetian Merchant 1563–81 Vijaynagar, Cambay, Goa, Orissa, Satgan/sati in Vijaynagar 7. Antoine Monserrate, SJ d. 1600 Portuguese Missionary 1570?–1600 Goa, Surat, Agra/sati near Agra 8. John Huyghen van Linschoten 1563–1611 Dutch Trader 1583–88 Goa, Surat, Malabar coast/sati near Goa 9. Ralph Fitch d. 1606? English Merchant 1583–91 Goa, Bijapur, Golconda, Agr/sati in Bidar near Golconda 10. Francesco Carletti 1573–1636 Florentine Court Official 1599–1601 Goa/sati in Vijaynagar 11. Francois Pyrard de Laval 1590?–1621? French Ship’s purser 1607–10 Goa, Calicut, Cochin, Ceylon, Chittagong/sati in Calicut 12. Henri de Feynes, M. de Montfort ? French Adventurer 1608–?20 Agra, Surat, Mangalore, Daman, Cochin, Ceylon, Bengal/sati in Sindh 13. William Hawkins d. 1613 English Trader 1608–12 Surat, Agra/sati in Agra 14. Pieter Gielisz van Ravesteyn (?) d. 1621 Dutch Factor 1608–14 Nizapatam, Surat 15.