Some Contrasting Visions of Luso-Tropicalism in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

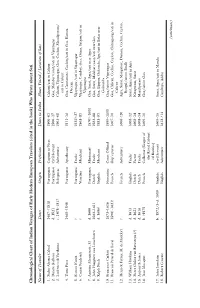

Who W Rote About Sati Name Of

Chronological Chart of Indian Voyages of Early Modern European Travelers (cited in the book) Who Wrote about Sati Name of Traveler Dates Origin Profession Dates in India Places Visited / Location of Sati 1. Pedro Alvares Cabral 1467–?1518 Portuguese Captain of Fleet 1500–01 Calicut/sati in Calicut 2. Duarte Barbosa d. 1521 Portuguese Civil Servant 1500–17 Goa, Malabar Coast/sati in Vijaynagar 3. Ludovico di Varthema c. 1475–1517 Bolognese Adventurer 1503–08 Calicut, Vijaynagar, Goa, Cochin, Masulipatam/ sati in Calicut 4. Tome Pires 1468–1540 Portuguese Apothecary 1511–16 Goa, Cannanore, Cochin/sati in Goa, Kanara, Deccan 5. Fernao Nuniz ? Portuguese Trader 1535?–37 Vijaynagar/sati in Vijaynagar 6. Caesar Frederick ? Venetian Merchant 1563–81 Vijaynagar, Cambay, Goa, Orissa, Satgan/sati in Vijaynagar 7. Antoine Monserrate, SJ d. 1600 Portuguese Missionary 1570?–1600 Goa, Surat, Agra/sati near Agra 8. John Huyghen van Linschoten 1563–1611 Dutch Trader 1583–88 Goa, Surat, Malabar coast/sati near Goa 9. Ralph Fitch d. 1606? English Merchant 1583–91 Goa, Bijapur, Golconda, Agr/sati in Bidar near Golconda 10. Francesco Carletti 1573–1636 Florentine Court Official 1599–1601 Goa/sati in Vijaynagar 11. Francois Pyrard de Laval 1590?–1621? French Ship’s purser 1607–10 Goa, Calicut, Cochin, Ceylon, Chittagong/sati in Calicut 12. Henri de Feynes, M. de Montfort ? French Adventurer 1608–?20 Agra, Surat, Mangalore, Daman, Cochin, Ceylon, Bengal/sati in Sindh 13. William Hawkins d. 1613 English Trader 1608–12 Surat, Agra/sati in Agra 14. Pieter Gielisz van Ravesteyn (?) d. 1621 Dutch Factor 1608–14 Nizapatam, Surat 15. -

Download Release 15

BIBLICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE Gordon E. Christo RELEASE15 The History of the Seventh-day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists Gordon E. Christo Biblical Research Institute Silver Spring, Maryland Copyright © 2020 by the Biblical Research Institute Silver Spring, Maryland www.adventistbiblicalresearch.org General editor: Ekkehardt Mueller Editor: Clinton Wahlen Managing editor: Marly Timm Editorial assistance and layout: Patrick V. Ferreira Copy editor: Schuyler Kline Author: Christo, Gordon Title: Te History of the Seventh-day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists Subjects: Sabbath - India Sabbatarians - India Call Number: V125.S32 2020 Printed in the U.S.A. ISBN 978-0-925675-42-2 Contents Introduction ............................................................................... 1 Early Presence of Jews in India ............................................. 3 Bene Israel ............................................................................. 3 Cochin Jews ........................................................................... 4 Early Christianity in India ....................................................... 6 Te Report of Pantaneus ................................................... 7 “Te Doctrine of the Apostles” ........................................ 8 Te Acts of Tomas ........................................................... 8 Traditions of the Tomas Christians ............................... 9 Tomas Christians and the Sabbath ....................................... 10 -

Conversion in the Pluralistic Religious Context of India: a Missiological Study

Conversion in the pluralistic religious context of India: a Missiological study Rev Joel Thattupurakal Mathai BTh, BD, MTh 0000-0001-6197-8748 Thesis submitted for the degree Philosophiae Doctor in Missiology at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University in co-operation with Greenwich School of Theology Promoter: Dr TG Curtis Co-Promoter: Dr JJF Kruger April 2017 Abstract Conversion to Christianity has become a very controversial issue in the current religious and political debate in India. This is due to the foreign image of the church and to its past colonial nexus. In addition, the evangelistic effort of different church traditions based on particular view of conversion, which is the product of its different historical periods shaped by peculiar constellation of events and creeds and therefore not absolute- has become a stumbling block to the church‘s mission as one view of conversion is argued against the another view of conversion in an attempt to show what constitutes real conversion. This results in competitions, cultural obliteration and kaum (closed) mentality of the church. Therefore, the purpose of the dissertation is to show a common biblical understanding of conversion which could serve as a basis for the discourse on the nature of the Indian church and its place in society, as well as the renewal of church life in contemporary India by taking into consideration the missiological challenges (religious pluralism, contextualization, syncretism and cultural challenges) that the church in India is facing in the context of conversion. The dissertation arrives at a theological understanding of conversion in the Indian context and its discussion includes: the multiple religious belonging of Hindu Christians; the dual identity of Hindu Christians; the meaning of baptism and the issue of church membership in Indian context. -

Of Goa, Daman And· Diu

• I'anaji, 15th October, 1970 !Asvina 23, 1892) SERIES III No. 29 OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENT OF GOA, DAMAN AND· DIU 6. Opposite 'Government Building No. 1'2 '(ISta. Inez) GOVERNMENT OF GOA, DAMAN 7. Opposite N. C. C. Office (Vaglo's House) DIU 8. T<>nca -(Near Chodancar's House) AND 9. Near [smail's House 10. :Opposite ,St. Francis Chapel 11. Near !Post Office- (Caranzalem) General Administration Department 112. Opposite Cafe Modema l(iPJ.edade S'hop) 13. At Cauleavaddo Office of the District Magistrate of Goa 14. Opposite Caetano Rodrigues House (Kerrant) 1'5. Opposite Our Lady 'of Rosary High School 16. Opposite Jui'lio Nogar's House Notification 17. Opposite Police Out Post 1,8. Near Govt. Primary School MAG/MY/70-NO~lQ4 1·9. Dona Paula. The District Magistrate 'Of Goa, Panaji, in exercise of his powers under Rule 7.12 'Of the Gea, 'Daman and Diu Meter d) Panaji-Dona Paula via Miramar Vehicles Rules 1965, hereby notifies the fellewing places as bus-steps en the fell ewing routes fer taking -up and setting 1. Near Azad Maidan -dewn 'Of passengers. 12. .Junction 'of the roads from the market and from the Goa Medical College Ne stage carriage shal1 take up 'Or set down passengers 3. Opposite Dr. Jack de Sequeira's House -except at the places shewn below as bus steps. 4. Near Oceanography Office Ne stage, carriage shan be halted at a bus-'stop for longer 5. Miramar than is necessary te take up such passengers as are awaiting -6. Tonca ,(Near Chodankar's House) when the vehicle arri'ves and to set down such passengers as 7. -

Outline Itinerary

About the tour: This historic tour begins in I Tech city Bangalore and proceed to the former princely state Mysore rich in Imperial heritage. Visit intrinsically Hindu collection of temples at Belure, Halebidu, Hampi, Badami, Aihole & Pattadakal, to see some of India's most intricate historical stone carvings. At the end unwind yourself in Goa, renowned for its endless beaches, places of worship & world heritage architecture. Outline Itinerary Day 01; Arrive Bangalore Day 02: Bangalore - Mysore (145kms/ 3hrs approx) Day 03: Mysore - Srirangapatna - Shravanabelagola - Hassan (140kms/ 3hrs approx) Day 04; Hassan – Belur – Halebidu – Hospet/ Hampi (310kms – 6-7hrs approx) Day 05; Hospet & Hampi Day 06; Hospet - Lakkundi – Gadag – Badami (130kms/ 3hrs approx) Day 07; Badami – Aihole – Pattadakal – Badami (80kms/ round) Day 08; Badami – Goa (250kms/ 5hrs approx) Day 09; Goa Day 10; Goa Day 11; Goa – Departure House No. 1/18, Top Floor, DDA Flats, Madangir, New Delhi 110062 Mob +91-9810491508 | Email- [email protected] | Web- www.agoravoyages.com Price details: Price using 3 star hotels valid from 1st October 2018 till 31st March 2019 (5% Summer discount available from 1st April till travel being completed before 30th September 2018 on 3star hotels price) Per person price sharing DOUBLE/ Per person price sharing TRIPLE (room Per person price staying in SINGLE Particular TWIN rooms with extra bed) rooms rooms Currency INR Euro USD INR Euro USD INR Euro USD 1 person N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A ₹180,797 € 2,260 $2,825 2 person ₹96,680 € 1,208 -

Download Individual TIFF Images for Personal Use

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title From Inquisition to E-Inquisition: A Survey of Online Sources on the Portuguese Inquisition Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05k4h9qb Journal Journal of Lusophone Studies, 4(2) ISSN 2469-4800 Author Pendse, Liladhar Publication Date 2020 DOI 10.21471/jls.v4i2.241 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California From Inquisition to E-Inquisition: A Survey of Online Sources on the Portuguese Inquisition LILADHAR R. PENDSE University of California, Berkeley Abstract: The Portuguese Inquisition in the colonies of the Empire remains understudied due to a lack of primary source materials that are available the researchers and educators. The advances in digital technologies and the current drive to foster Open Access have allowed us to understand better the relations among the complex set of circumstances as well as the mechanisms that, in their totality, represent the Portuguese Inquisition. The present paper seeks to answer questions that vary from describing these resources to identifying the institutions that created them. Digitized resources serve as a surrogate of the originals, and we can leverage the access to these electronic surrogates and enhance our understanding of the mechanisms of inquisition through E-Inquisitional objects in pedagogy and research. Keywords: Empire, Brazil, India, Africa, archives, open access The study of the history of the Portuguese Inquisition and its institutions has acquired importance in the context of early efforts to convert, indoctrinate, organize and “civilize” the large native and indigenous populations over the vast global expanse of the Portuguese Empire. From the beginning, the Portuguese Crown formed an alliance with the Catholic Church to promote proselytization in its early colonial acquisitions in India. -

Best Religious Sites in Goa"

"Best Religious Sites in Goa" Created by: Cityseeker 14 Locations Bookmarked Shree Shantadurga Temple "Peace-maker" Shree Shantadurga Temple is located in the village of Kavlem in Ponda. Built in 1713, this temple is considered to be the largest temple in Goa. Devoted to the Goddess Shantadurga or Jagdamba, the temple contains a large idol of Shantadurga, or the Goddess of Peace. You will find her idol standing between the fiery statues of Gods Vishnu and Shiva so as to quell the brewing quarrel between them. ,Like other temples in Goa, this one, too, has an annual jatra held during the month of February. This temple also has provision for lodging called agrashalas to aid devotees. +91 832 231 2557 shreeshantadurga.com [email protected] Shantadurga Devasthan, om Ponda Safa Masjid "Histroric Mosque" The Safa Masjid at Ponda is 'one' Islamic structure in the city to have withstood the Portuguese and the Maratha rule. This mosque was built in the early 1560s by Ibhrahim Adilshah, the then Sultan of Bijapur. Famous for its architecture, the mosque is a 'single chambered' structure with complete laterite flooring, carpet paintings and scripts from the Holy Quran adorning the walls from within. The main prayer hall at the mosque is open only for Muslim devotees. Muslims in and around the city assemble at the mosque during Ramadan, the Id-ul-Fitr, the Friday afternoon prayers and other community celebrations. +91 832 222 3412 (Tourist Information) Safa Masjid Main Road, Off National Highway 4, Ponda Shri Mangesh Devasthan (Shri Mangueshi Temple) "In Memory of Lord Shiva" An entrance lined up with local vendors selling incense, flowers and other devotional offerings, and a flight of bricked steps dotted with clay lamps lead you to one of the most visited religious sites in South Goa, the Mangueshi Temple. -

Day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-Day Adventists

The History of the Seventh- day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists Biblical Research Institute Release – 15 Gordon E. Christo The History of the Seventh- day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists Gordon E. Christo Biblical Research Institute Silver Spring, Maryland Copyright © 2020 by the Biblical Research Institute Silver Spring, Maryland www.adventistbiblicalresearch.org General editor: Ekkehardt Mueller Editor: Clinton Wahlen Managing editor: Marly Timm Editorial assistance and layout: Patrick V. Ferreira Copy editor: Schuyler Kline Author: Christo, Gordon Title: Te History of the Seventh-day Sabbath in India Until the Arrival of Seventh-day Adventists Subjects: Sabbath - India Sabbatarians - India Call Number: V125.S32 2020 Printed in the U.S.A. by the Pacifc Press Publishing Association Nampa, ID 83653-5353 ISBN 978-0-925675-42-2 Contents Introduction ............................................................................... 1 Early Presence of Jews in India ............................................. 3 Bene Israel ............................................................................. 3 Cochin Jews ........................................................................... 4 Early Christianity in India ....................................................... 6 Te Report of Pantaneus ................................................... 7 “Te Doctrine of the Apostles” ........................................ 8 Te Acts of Tomas .......................................................... -

November 2019

H Computer Science H Electronics & Communication H Information Science H Electrical & Electronics H Mechanical H Civil H Automobile M.B.A., M.C.A., M.Tech., NEW HORIZON TIMES Ph.D., M.Sc., (Engg) A MONTHLY NEWSPAPER FOR THE STUDENTS AND BY THE STUDENTS Bangalore, November 2019 CMM/BHE/DECL/NPP - 230 / 10 / 2033 GOA TRIP (STD X TRIP) DELHI, VRINDAVAN, JAIPUR TRIP(STD IX TRIP) O n 2 9 t h September, we the 9th graders were seen at the a i r p o r t . All extremely eager to go on this trip to visit new The tenth graders could not have been more excited for their long awaited places and Goa trip! We left for Kempegowda International airport at 2 a.m. All of us t o s p e n d were way too excited to be sleepy. We landed at Goa International airport at t i m e w i t h around 8 a.m. We were welcomed to Paradise beach village resort with our friends. flower garlands. After freshening up, we headed to Chapora fort. The ruins overlooked a magnificent view of the Chapora river draining into the Arabian The first place we visited was Delhi. We visited national landmarks like the sea. After lunch at the resort, we were allotted our rooms. Next, we headed Red Fort, the India Gate and viewed the Parliament. We also visited to the famous Aguada fort which is well preserved and situated on Sinquerim Akshardham, where we were awed by the spectacular water show and by beach where we caught a glimpse of a gorgeous beach sunset. -

Preserving Transcultural Heritage.Indb

Edited by Joaquim Rodrigues dos Santos PRESERVING TRANSCULTURAL HERITAGE: YOUR WAY OR MY WAY? Questions on Authenticity, Identity and Patrimonial Proceedings in the Safeguarding of Architectural Heritage Created in the Meeting of Cultures TITLE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Preserving Transcultural Heritage: Joaquim Rodrigues dos Santos (chairman) Your Way or My Way? Maria de Magalhães Ramalho Questions on Authenticity, Identity and Patrimonial Inês Cristovão Proceedings in the Safeguarding of Architectural Tiago Rodrigues Heritage Created in the Meeting of Cultures Cátia Reis Vera Mariz EDITOR Luis Urbano Afonso Joaquim Rodrigues dos Santos Margarida Donas Botto (ARTIS – Institute of Art History, School of Arts and Humanities, University of Lisbon) The authors are responsible for their texts and the images contained on them, including the correct SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE reference of their sources and the permissions from Vítor Serrão (chairman) the copyright owners. Ana Tostões Christopher Marrion Francisco Lopez Morales LAYOUT Gill Chitty Fernanda Cavalheiro Giovanni Carbonara Margarida de Almeida Hélder Carita Javier Rivera Blanco ISBN Joaquim Rodrigues dos Santos 978-989-658-467-2 Johannes Widodo Jorge Correia DOI José Delgado Rodrigues 10.30618/978-989-658-467-2 Kassim Omar Khalid El Harrouni LEGAL DEPOSIT NUMBER Luís Urbano Afonso 428851/17 Maria João Neto Maria Lúcia Bressan Pinheiro ISSUE Nobuko Inaba 07.2017 Olga Sevan Paulo Peixoto Rabindra Vasavada Rosa Perez Rui Fernandes Póvoas Susan Jackson-Stepowski EDIÇÃO Tamás Fejérdy CALEIDOSCÓPIO -

Μgrow and Spread Your Wings¶

Globalization and opening up of economy has turned the world into a global village. Any enterprising businessman cannot turn a blind eye to this change. µGrow and spread your wings¶ - fuelled by this corporate philosophy, Akbar Travels has widened its network by opening branches, catering to the high flying and need-based patrons in India and overseas. MUMBAI : Mumbai, the financial capital and business powerhouse of India, is the headquarters of Akbar Travels. It provides a 24-hr service facility with conveniently located branches in: y Crawford Market The birthplace of Akbar Travels since 1978 and the headquarters of the Akbar Network,this branch plays a pivotal role in the company¶s productivity. y C.S.T.Located opposite the most popular landmark, this branch provides its services to South Mumbai. y Dadar This particular branch is located to serve the Central Zone of Mumbai. y Andheri The most developing area of the Mumbai suburbs with Multinational Corporates, Seepz and MIDC. Akbar Travels opened a branch here to reach out to the North Mumbai people. y PUNE : The cultural capital of Maharashtra is spreading its wings into the industrial sector and is now the Info Tech center of the western region. Akbar Travels realized the strategic importance of this developing city and opened branches here to serve the multinationals and the young population. Today, Pune branch has become the hub for the hinterland of Maharashtra regions. y TAMIL NADU : Akbar Travel¶s strategic move of opening branches in Chennai in 1996 gave a checkmate to all the other established agencies in this state of temples and jasmine. -

Altinho, Panaji Goa

Government of Goa. O/o the Principal Chief Engineer, Public Works Department, Altinho , Panaji Goa. No. 34 / 8 /2013-14/PCE/ PWD / 296 Dated: - 10 th January 2014. Instruction to the candidates for appearing Computer Test to the post of Assistant Data Entry Operator in PWD applied in response to the Advertisement No.34/8/2011/PCE-PWD-ADM(II)/575, dated 04.04.2013 appeared on daily newspaper viz Navhind Times, Herald, Sunaparant & Gomantak dated 06.04.2013: 1. Venue of Examination Centre - Information Technology Department of Goa College of Engineering, Farmagudi – Ponda. 2. Seat No., Name of the candidates and Date of Computer Test – As shown in the Annexure “A” and “B” 3. Candidates are advised to peruse the details as displayed on the website and in case of any discrepancy noticed or any grievance as regards the list published, pertaining to their application, they may contact at the Office of Principal Chief Engineer (ADM-II), PWD, Altinho, Panaji on or before 14.01.2014 , failing which it will be presume that all the details are correct as published and no further corrections/ correspondence will be entertained. 4. No individual call letter or intimation shall be sent to the candidates. 5. The candidates will be allowed to enter the examination hall and appear for computer test only upon producing valid identity proof, preferably EPIC, Driving Licence, Passport etc. 6. Bus service from Farmagudi Circle to Goa Engineering College to the candidates appearing for the test is available every half an hour according to the Test Schedule free of cost to and fro from College Campus to Farmagudi Circle.