Preserving Transcultural Heritage.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newspaper Wise.Xlsx

PRINT MEDIA COMMITMENT REPORT FOR DISPLAY ADVT. DURING 2013-2014 CODE NEWSPAPER NAME LANGUAGE PERIODICITY COMMITMENT(%)COMMITMENTCITY STATE 310672 ARTHIK LIPI BENGALI DAILY(M) 209143 0.005310639 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS ENGLISH DAILY(M) 775695 0.019696744 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1618569 0.041099322 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ENGLISH DAILY(M) 482558 0.012253297 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI TELUGU DAILY(M) 534260 0.013566134 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 776771 0.019724066 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 201424 0.005114635 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410522 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 6550 0.00016632 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410370 SAKSHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 1417145 0.035984687 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 546688 0.01388171 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410400 TELUGU WAARAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 154046 0.003911595 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410495 VINIYOGA DHARSINI TELUGU MONTHLY 18771 0.00047664 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY TELUGU DAILY(E) 69244 0.00175827 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410449 NETAJI TELUGU DAILY(E) 153965 0.003909538 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410012 ELURU TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) 65899 0.001673333 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410117 GOPI KRISHNA TELUGU DAILY(M) 172484 0.00437978 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410009 RATNA GARBHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 67128 0.00170454 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410114 STATE TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) -

Annualrepeng II.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT – 2007-2008 For about six decades the Directorate of Advertising and on key national sectors. Visual Publicity (DAVP) has been the primary multi-media advertising agency for the Govt. of India. It caters to the Important Activities communication needs of almost all Central ministries/ During the year, the important activities of DAVP departments and autonomous bodies and provides them included:- a single window cost effective service. It informs and educates the people, both rural and urban, about the (i) Announcement of New Advertisement Policy for nd Government’s policies and programmes and motivates print media effective from 2 October, 2007. them to participate in development activities, through the (ii) Designing and running a unique mobile train medium of advertising in press, electronic media, exhibition called ‘Azadi Express’, displaying 150 exhibitions and outdoor publicity tools. years of India’s history – from the first war of Independence in 1857 to present. DAVP reaches out to the people through different means of communication such as press advertisements, print (iii) Multi-media publicity campaign on Bharat Nirman. material, audio-visual programmes, outdoor publicity and (iv) A special table calendar to pay tribute to the exhibitions. Some of the major thrust areas of DAVP’s freedom fighters on the occasion of 150 years of advertising and publicity are national integration and India’s first war of Independence. communal harmony, rural development programmes, (v) Multimedia publicity campaign on Minority Rights health and family welfare, AIDS awareness, empowerment & special programme on Minority Development. of women, upliftment of girl child, consumer awareness, literacy, employment generation, income tax, defence, DAVP continued to digitalize its operations. -

Audit-Reg-Corp.Pdf

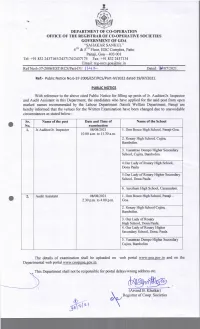

Venues for the post of Jr. Auditor/Jr. Inspector Date and Day: Sunday 08.08.2021 Time:10.00 a.m. to 11.30 a.m. Morning Session Sr. Name of the School Roll No. No. 1. Don Bosco High School, Panaji – Goa 1 to 500 2. Rosary High School, Cujira, Bambolim 501 to 940 3. Vasantrao Dempo Higher Secondary 941 to 1063 School, Cujira, Bambolim 4. Our Lady of Rosary High School, 1064 to 1339 Dona Paula 5. Our Lady of Rosary Higher Secondary 1340 to 1539 School, Dona Paula 6. Auxilium High School, Caranzalem 1540 to 1639 Venues for the post of Audit Assistant Date and Day: Sunday 08.08.2021 Time: 2.30 p.m. to 4.00 p.m. Evening Session Sr. Name of the School Roll No. No. 1. Don Bosco High School, Panaji – Goa 1 to 500 2. Rosary High School, Cujira, Bambolim 501 to 940 3. Our Lady of Rosary High School, 941 to 1240 Dona Paula 4. Our Lady of Rosary Higher Secondary 1241 to 1440 School, Dona Paula 5. Vasantrao Dempo Higher Secondary 1441 to 1546 School, Cujira, Bambolim 1 List of the Candidates for the post of Audit Assistant for examination to be held on 08/08/2021 at 2.30 p.m. to 4.00 p.m. In Don Bosco High School, Panaji-Goa from Roll No. 001 to 500 Roll No. Name & Address of the Candidate 001 Muriel Philip D’ Souza, H. No. 156, Angod, Mapusa, Bardez Goa. 002 Nivedita Sudhakar Achari, H. No. 271, khareband Road, Margao Goa 403601. -

Ch. 3 MALE DEITIES I. Worship of Vishnu and Its Forms in Goa Vishnu

Ch. 3 MALE DEITIES I. Worship of Vishnu and its forms in Goa Vishnu is believed to be the Preserver God in the Hindu pantheon today. In the Vedic text he is known by the names like Urugai, Urukram 'which means wide going and wide striding respectively'^. In the Rgvedic text he is also referred by the names like Varat who is none other than says N. P. Joshi^. In the Rgvedhe occupies a subordinate position and is mentioned only in six hymns'*. In the Rgvedic text he is solar deity associated with days and seasons'. References to the worship of early form of Vishnu in India are found in inscribed on the pillar at Vidisha. During the second to first century BCE a Greek by name Heliodorus had erected a pillar in Vidisha in the honor of Vasudev^. This shows the popularity of Bhagvatism which made a Greek convert himself to the fold In the Purans he is referred to as Shripati or the husband oiLakshmi^, God of Vanmala ^ (wearer of necklace of wild flowers), Pundarikaksh, (lotus eyed)'". A seal showing a Kushan chief standing in a respectful pose before the four armed God holding a wheel, mace a ring like object and a globular object observed by Cunningham appears to be one of the early representations of Vishnu". 1. Vishnu and its attributes Vishnu is identified with three basic weapons which he holds in his hands. The conch, the disc and the mace or the Shankh. Chakr and Gadha. A. Shankh Termed as Panchjany Shankh^^ the conch was as also an essential element of Vishnu's identity. -

New Arrival in Academy Library

New Arrival in Academy Library SL Name of Books Authors Name 1 The Book of Five Rings Miyamoto Musashi 2 The Creator's Code Amy Wilkinson 3 Kanthapura Raja Rao 4 Gods, Kings and Slaves R. Venketesh 5 Untouchable Mulk Raj Anand 6 Heart of Darkness Joseph Conrad 7 Make Your Bed William H. Mcraven 8 Give and Take Adam Grant 9 The Guns of August Barbara Tuchman 10 The Craft of Intelligence Allen W. Dulles 11 Parties and Electoral Politics In Northeast India V. Bijukumar 12 The ISI of Pakistan : Faith, Unity, Discipline Hein G. Kiessling 13 China's India War Bertil Lintner 14 The China Pakistan Axis Andrew Small The Hard Thing About Hard Things : Builing A Business When There Are No 15 Easy Answers Ben Horowitz 16 Great Game East Bertil Lintner 17 Ashtanga Yoga John Scott 18 1962 : The war that wasn't Shiv Kunal Verma 19 Sins of Gods : Warriors of Dharma Dr. Chandraanshu 20 Legal And Professional Writing And Drafting In Plain Language Dr. K. R. Chandratre 21 Line on Fire Happymon Jacob 22 Mocktails : Recipe Book Vivian Miller 23 An End To Suffering: The Buddha In The World Pankaj Mishra 24 The Seventy Great Mysteries of The Ancient World Brian M. Fagan 25 Dragon on Our Doorstep Pravin Sawhney ,Ghazala 26 A Handful of Sesame Shrinivas Vaidya , MKarnoor 27 The Biology of Belief Bruce H. Lipton 28 Hkkjr % usg: ds ckn jkepUnz xqgk 29 Indian Polity : For Civil Services Examinations M Laxmikanth 30 India Super Goods : Change The Way You Eat Rujuta Diwekar 31 A Book For Government Officials To Master: Noting And Drafting M.K. -

Caste, Materiality and Embodiment: Questioning the Idealism/ Materialism Debate

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 200–216 February 2020 brandeis.edu/j-caste ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v1i1.123 Caste, Materiality and Embodiment: Questioning the Idealism/ Materialism Debate Subro Saha1 (Bluestone Rising Scholar Honorable Mention 2019) Abstract Exploring the contingencies and paradoxes shaping the idealism/materialism separation in absolutist terms, this paper attempts to analyze the problems of such separatist tendencies in terms of dealing with the question of caste. Engaging with the problems of separating ‘idea’ and ‘matter’ in relation to the three dominant aspects that shape the conceptualisation of caste—origin(s), body, and society—the paper presents caste as an enmeshed idea-matter embrace that gains its circulation in practice through embodiment. Aiming to counter caste with its own logic and internal contradictions, the paper further proceeds to show that these three aspects that had otherwise been seen for a long time as shaping caste also contradict their own efficacy and logic. With such an approach the paper presents caste as a ghost that feeds on our embodied ideas. Further, bringing in the trope of (mis)reading, the paper tries to examine the intricacies haunting any attempt to deal with the ghost. The paper therefore, can be seen as a humble effort at reminding the necessity of reading the idea of caste in its spectralities and continuous figurations. Keywords Caste, idealism, materiality, touch, embodiment Introduction Despite all diverse attempts to get rid of caste, its persistence reminds us continuously of its haunting spectrality that even after so much beating refuses to die.1 It haunts us like a ghost whose origin and functional modalities continue to baffle us with its shifting trajectories and (trans)formative capacities, and thus continuously challenges our approaches to exorcise it. -

Chapter 6: EPILOGUE I. Significance of the Study A) the Study Is Basically

Chapter 6: EPILOGUE I. Significance of the study a) The study is basically a very good documentation of Goa's ancient and medieval period icons and sculptural remains. So far a wrong notion among many that Goa religio cultural past before the arrival of the Portuguese is intangible has been critically viewed and examined in this study. The research would help in throwing light on the pre-Portuguese era of the Goa's history. b) The craze of modernization and renovation of ancient and historic temples have made changes in the religio-cultural aspect of the society. Age old deities and concepts of worships have been replaced with new sculptures or icons. The new sculptures installed in places of the historic ones have been modified to the whims and fancies of many trustees or temple authorities thus changing the pattern of the religio-cultural past. While new icons substitute the old ones there are changes in attributes, styles and the historic features of the sculpture or image. Not just this but the old sculptures are immersed in water when the new one is being installed. Some customary rituals have been rapidly changed intentionally or unintentionally by the stake holders or the devotees. Moreover the most of the ancient rituals and customs associated with some icons have are in process of being stopped by the locals. Therefore a thorough documentation of these sculptures and antiquities with scientific attitude and research was the need of the hour. c) The iconographic details about many sculptures, worships or deities are scattered in many books and texts. -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed. -

O. G. Series III No. 29.Pmd

Reg. No. G-2/RNP/GOA/32/2011-12 RNI No. GOAENG/2002/6410 Panaji, 16th October, 2014 (Asvina 24, 1936) SERIES III No. 29 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY GOVERNMENT OF GOA Act, 1982 & Rules, 1985, as amended from time to time, the registration of Vehicle No. GA-07/F-0665 Department of Tourism belonging to Shri Joaquim Viegas, r/o 430/A, ___ Posrembhat, Taleigao, Goa, entered in Register Order No. 28 at page No. 24 is hereby removed as the said Tourist Taxi has been transferred to other State No. 5/TTR(1960)2011-DT/1705 Kerala with effect from 16-08-2013 bearing No. -. In pursuance of sub-section 1(A) of Section 17, Panaji, 7th October, 2014.— The Dy. Director of read with Rule 4 of Goa Registration of Tourist Trade Tourism & Prescribed Authority (North Zone), Arvind Act, 1982 & Rules, 1985, as amended from time to B. Khutkar. time, the registration of Vehicle No. GA-07/F-0667 __________ belonging to Shri Joaquim Viegas, r/o 430, Posrembhat, Taleigao, Goa, entered in Register Order No. 28 at page No. 15 is hereby removed as the said No. 5/TTR(1956)2011-DT/1708 Tourist Taxi has been transferred to other State i.e. In pursuance of sub-section 1(A) of Section 17, Kerala with effect from 16-08-2013 bearing No. -. read with Rule 4 of Goa Registration of Tourist Trade Panaji, 7th October, 2014.— The Dy. Director of Act, 1982 & Rules, 1985, as amended from time to Tourism & Prescribed Authority (North Zone), Arvind time, the registration of Vehicle No. -

April 2018 E-ISSN: 2456-5571 UGC Approved Journal (J

BODHI International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Science An Online, Peer reviewed, Refereed and Quarterly Journal Vol: 2 Special Issue: 3 April 2018 E-ISSN: 2456-5571 UGC approved Journal (J. No. 44274) CENTRE FOR RESOURCE, RESEARCH & PUBLICATION SERVICES (CRRPS) www.crrps.in | www.bodhijournals.com BODHI BODHI International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Science (ISSN: 2456-5571) is online, peer reviewed, Refereed and Quarterly Journal, which is powered & published by Center for Resource, Research and Publication Services, (CRRPS) India. It is committed to bring together academicians, research scholars and students from all over the world who work professionally to upgrade status of academic career and society by their ideas and aims to promote interdisciplinary studies in the fields of humanities, arts and science. The journal welcomes publications of quality papers on research in humanities, arts, science. agriculture, anthropology, education, geography, advertising, botany, business studies, chemistry, commerce, computer science, communication studies, criminology, cross cultural studies, demography, development studies, geography, library science, methodology, management studies, earth sciences, economics, bioscience, entrepreneurship, fisheries, history, information science & technology, law, life sciences, logistics and performing arts (music, theatre & dance), religious studies, visual arts, women studies, physics, fine art, microbiology, physical education, public administration, philosophy, political sciences, psychology, population studies, social science, sociology, social welfare, linguistics, literature and so on. Research should be at the core and must be instrumental in generating a major interface with the academic world. It must provide a new theoretical frame work that enable reassessment and refinement of current practices and thinking. This may result in a fundamental discovery and an extension of the knowledge acquired. -

Of Goa, Daman And· Diu

• I'anaji, 15th October, 1970 !Asvina 23, 1892) SERIES III No. 29 OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENT OF GOA, DAMAN AND· DIU 6. Opposite 'Government Building No. 1'2 '(ISta. Inez) GOVERNMENT OF GOA, DAMAN 7. Opposite N. C. C. Office (Vaglo's House) DIU 8. T<>nca -(Near Chodancar's House) AND 9. Near [smail's House 10. :Opposite ,St. Francis Chapel 11. Near !Post Office- (Caranzalem) General Administration Department 112. Opposite Cafe Modema l(iPJ.edade S'hop) 13. At Cauleavaddo Office of the District Magistrate of Goa 14. Opposite Caetano Rodrigues House (Kerrant) 1'5. Opposite Our Lady 'of Rosary High School 16. Opposite Jui'lio Nogar's House Notification 17. Opposite Police Out Post 1,8. Near Govt. Primary School MAG/MY/70-NO~lQ4 1·9. Dona Paula. The District Magistrate 'Of Goa, Panaji, in exercise of his powers under Rule 7.12 'Of the Gea, 'Daman and Diu Meter d) Panaji-Dona Paula via Miramar Vehicles Rules 1965, hereby notifies the fellewing places as bus-steps en the fell ewing routes fer taking -up and setting 1. Near Azad Maidan -dewn 'Of passengers. 12. .Junction 'of the roads from the market and from the Goa Medical College Ne stage carriage shal1 take up 'Or set down passengers 3. Opposite Dr. Jack de Sequeira's House -except at the places shewn below as bus steps. 4. Near Oceanography Office Ne stage, carriage shan be halted at a bus-'stop for longer 5. Miramar than is necessary te take up such passengers as are awaiting -6. Tonca ,(Near Chodankar's House) when the vehicle arri'ves and to set down such passengers as 7. -

The Case of Goa, India

109 ■ Article ■ The Formation of Local Public Spheres in a Multilingual Society: The Case of Goa, India ● Kyoko Matsukawa 1. Introduction It was Jurgen Habermas, in his Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere [1991(1989)], who drew our attention to the relationship between the media and the public sphere. Habermas argued that the public sphere originated from the rational- critical discourse among the reading public of newspapers in the eighteenth century. He further claimed that the expansion of powerful mass media in the nineteenth cen- tury transformed citizens into passive consumers of manipulated public opinions and this situation continues today [Calhoun 1993; Hanada 1996]. Habermas's description of historical changes in the public sphere summarized above is based on his analysis of Europe and seems to come from an assumption that the mass media developed linearly into the present form. However, when this propo- sition is applied to a multicultural and multilingual society like India, diverse forms of media and their distribution among people should be taken into consideration. In other words, the media assumed their own course of historical evolution not only at the national level, but also at the local level. This perspective of focusing on the "lo- cal" should be introduced to the analysis of the public sphere (or rather "public spheres") in India. In doing so, the question of the power of language and its relation to culture comes to the fore. 松 川 恭 子Kyoko Matsukawa, Faculty of Sociology, Nara University. Subject: Cultural Anthropology. Articles: "Konkani and 'Goan Identity' in Post-colonial Goa, India", in Journal of the Japa- nese Association for South Asian Studies 14 (2002), pp.121-144.