Natural Resources Management Needs for Coastal and Littoral Marine Ecosystems of the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastal Zone Management Act Section 309 Program Guidance

Guam Coastal Management Program Bureau of Statistics and Plans 2020-2025 DRAFT October 2020 This document was prepared for the Guam Coastal Management Program (GCMP) under the Bureau of Statistics and Plans (BSP), with financial assistance provided by the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended, administered by the Office for Coastal Management (OCM), National Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The statements, findings, and conclusions are those of the authors and not necessarily reflect the views of NOAA. Suggested citation: Bureau of Statistics and Plans – Guam Coastal Management Program (BSP-GCMP). 2020. 2020-2025 Section 309 Assessment and Strategy Report. For more information about this report please contact the Guam Coastal Management Program at 671.472.4201/2/3 or Edwin Reyes, Coastal Program Administrator at [email protected]. Table of Contents I. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 II. Summary of Recent Section 309 Achievements ................................................................................................ 3 2011-2015 Section 309 Achievements ...................................................................................................................... 3 2015-2020 Section 309 Achievements ...................................................................................................................... 5 III. Assessment ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Geography and Archaeology of the Palm Islands and Adjacent Continental Shelf of North Queensland

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following work: O’Keeffe, Mornee Jasmin (1991) Over and under: geography and archaeology of the Palm Islands and adjacent continental shelf of North Queensland. Masters Research thesis, James Cook University of North Queensland. Access to this file is available from: https://doi.org/10.25903/5bd64ed3b88c4 Copyright © 1991 Mornee Jasmin O’Keeffe. If you believe that this work constitutes a copyright infringement, please email [email protected] OVER AND UNDER: Geography and Archaeology of the Palm Islands and Adjacent Continental Shelf of North Queensland Thesis submitted by Mornee Jasmin O'KEEFFE BA (QId) in July 1991 for the Research Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts of the James Cook University of North Queensland RECORD OF USE OF THESIS Author of thesis: Title of thesis: Degree awarded: Date: Persons consulting this thesis must sign the following statement: "I have consulted this thesis and I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author,. and to make proper written acknowledgement for any assistance which ',have obtained from it." NAME ADDRESS SIGNATURE DATE THIS THESIS MUST NOT BE REMOVED FROM THE LIBRARY BUILDING ASD0024 STATEMENT ON ACCESS I, the undersigned, the author of this thesis, understand that James Cook University of North Queensland will make it available for use within the University Library and, by microfilm or other photographic means, allow access to users in other approved libraries. All users consulting this thesis will have to sign the following statement: "In consulting this thesis I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author; and to make proper written acknowledgement for any assistance which I have obtained from it." Beyond this, I do not wish to place any restriction on access to this thesis. -

Bibliography on Fisheries and Aquaculture

Secretariat of the Pacific Community 4th SPC Heads of Fisheries Meeting (30 August – 3 September 2004, Noumea, New Caledonia) Information Paper 6 Original: English Bibliography on Fisheries and Aquaculture www.spc.int/library BIBLIOGRAPHY ON FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE 1 Conference delegates, The librarians of the SPC are pleased to offer delegates to the 4th Heads of Fisheries Meeting a Bibliography on Fisheries and Aquaculture in Oceania. SPC Library also has an excellent collection of materials on fisheries in general. Please consult the library catalogue, at the website given below, for these publications. If you are interested in having a copy of any of the documents in this bibliography, please contact us as soon as possible. We can provide photocopies for you at the meeting. Certain of these items are also available directly from the SPC Publications Office. Access to the library catalogue is at: www.spc.int/library Welcome to the Online Catalog of SPC Library Select the operation that you want to perform: Search only SPC Publications/Documents Subject Specific Search Screens Search by Author Search by Journal Title Search by Subject Search by Title Search Multiple Fields You can contact us by e-mail at [email protected] Rachele Oriente Anne Gibert Librarian Librarian Assistant 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I – Fisheries in Oceania (by countries and territories) 1. American Samoa p. 4 2. Cook Islands p. 7 3. Fedederated States of Micronesia p. 11 4. Fiji Islands p. 13 5. French Polynesia p. 20 6. Guam p. 25 7. Kiribati p. 28 8. Marshall Islands p. 33 9. -

Coastal Circulation and Water-Column Properties in The

Coastal Circulation and Water-Column Properties in the War in the Pacific National Historical Park, Guam— Measurements and Modeling of Waves, Currents, Temperature, Salinity, and Turbidity, April–August 2012 Open-File Report 2014–1130 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey FRONT COVER: Left: Photograph showing the impact of intentionally set wildfires on the land surface of War in the Pacific National Historical Park. Right: Underwater photograph of some of the healthy coral reefs in War in the Pacific National Historical Park. Coastal Circulation and Water-Column Properties in the War in the Pacific National Historical Park, Guam— Measurements and Modeling of Waves, Currents, Temperature, Salinity, and Turbidity, April–August 2012 By Curt D. Storlazzi, Olivia M. Cheriton, Jamie M.R. Lescinski, and Joshua B. Logan Open-File Report 2014–1130 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2014 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Suggested citation: Storlazzi, C.D., Cheriton, O.M., Lescinski, J.M.R., and Logan, J.B., 2014, Coastal circulation and water-column properties in the War in the Pacific National Historical Park, Guam—Measurements and modeling of waves, currents, temperature, salinity, and turbidity, April–August 2012: U.S. -

Part I. an Annotated Checklist of Extant Brachyuran Crabs of the World

THE RAFFLES BULLETIN OF ZOOLOGY 2008 17: 1–286 Date of Publication: 31 Jan.2008 © National University of Singapore SYSTEMA BRACHYURORUM: PART I. AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF EXTANT BRACHYURAN CRABS OF THE WORLD Peter K. L. Ng Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, Kent Ridge, Singapore 119260, Republic of Singapore Email: [email protected] Danièle Guinot Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, Département Milieux et peuplements aquatiques, 61 rue Buffon, 75005 Paris, France Email: [email protected] Peter J. F. Davie Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane, Queensland, Australia Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT. – An annotated checklist of the extant brachyuran crabs of the world is presented for the first time. Over 10,500 names are treated including 6,793 valid species and subspecies (with 1,907 primary synonyms), 1,271 genera and subgenera (with 393 primary synonyms), 93 families and 38 superfamilies. Nomenclatural and taxonomic problems are reviewed in detail, and many resolved. Detailed notes and references are provided where necessary. The constitution of a large number of families and superfamilies is discussed in detail, with the positions of some taxa rearranged in an attempt to form a stable base for future taxonomic studies. This is the first time the nomenclature of any large group of decapod crustaceans has been examined in such detail. KEY WORDS. – Annotated checklist, crabs of the world, Brachyura, systematics, nomenclature. CONTENTS Preamble .................................................................................. 3 Family Cymonomidae .......................................... 32 Caveats and acknowledgements ............................................... 5 Family Phyllotymolinidae .................................... 32 Introduction .............................................................................. 6 Superfamily DROMIOIDEA ..................................... 33 The higher classification of the Brachyura ........................ -

Cairns Regional Council Water and Waste Report for Mulgrave River Aquifer Feasibility Study Flora and Fauna Report

Cairns Regional Council Water and Waste Report for Mulgrave River Aquifer Feasibility Study Flora and Fauna Report November 2009 Contents 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Scope 1 1.3 Project Study Area 2 2. Methodology 4 2.1 Background and Approach 4 2.2 Demarcation of the Aquifer Study Area 4 2.3 Field Investigation of Proposed Bore Hole Sites 5 2.4 Overview of Ecological Values Descriptions 5 2.5 PER Guidelines 5 2.6 Desktop and Database Assessments 7 3. Database Searches and Survey Results 11 3.1 Information Sources 11 3.2 Species of National Environmental Significance 11 3.3 Queensland Species of Conservation Significance 18 3.4 Pest Species 22 3.5 Vegetation Communities 24 3.6 Regional Ecosystem Types and Integrity 28 3.7 Aquatic Values 31 3.8 World Heritage Values 53 3.9 Results of Field Investigation of Proposed Bore Hole Sites 54 4. References 61 Table Index Table 1: Summary of NES Matters Protected under Part 3 of the EPBC Act 5 Table 2 Summary of World Heritage Values within/adjacent Aquifer Area of Influence 6 Table 3: Species of NES Identified as Occurring within the Study Area 11 Table 4: Summary of Regional Ecosystems and Groundwater Dependencies 26 42/15610/100421 Mulgrave River Aquifer Feasibility Study Flora and Fauna Report Table 5: Freshwater Fish Species in the Mulgrave River 36 Table 6: Estuarine Fish Species in the Mulgrave River 50 Table 7: Description of potential borehole field in Aloomba as of 20th August, 2009. 55 Figure Index Figure 1: Regional Ecosystem Conservation Status and Protected Species Observation 21 Figure 2: Vegetation Communities and Groundwater Dependencies 30 Figure 3: Locations of Study Sites 54 Appendices A Database Searches 42/15610/100421 Mulgrave River Aquifer Feasibility Study Flora and Fauna Report 1. -

Some Thoughts and Personal Opinions About Molluscan Scientific Names

A name is a name is a name: some thoughts and personal opinions about molluscan scientifi c names S. Peter Dance Dance, S.P. A name is a name is a name: some thoughts and personal opinions about molluscan scien- tifi c names. Zool. Med. Leiden 83 (7), 9.vii.2009: 565-576, fi gs 1-9.― ISSN 0024-0672. S.P. Dance, Cavendish House, 83 Warwick Road, Carlisle CA1 1EB, U.K. ([email protected]). Key words: Mollusca, scientifi c names. Since 1758, with the publication of Systema Naturae by Linnaeus, thousands of scientifi c names have been proposed for molluscs. The derivation and uses of many of them are here examined from various viewpoints, beginning with names based on appearance, size, vertical distribution, and location. There follow names that are amusing, inventive, ingenious, cryptic, ideal, names supposedly blasphemous, and names honouring persons and pets. Pseudo-names, diffi cult names and names that are long or short, over-used, or have sexual connotations are also examined. Pertinent quotations, taken from the non-scientifi c writings of Gertrude Stein, Lord Byron and William Shakespeare, have been incorporated for the benefi t of those who may be inclined to take scientifi c names too seriously. Introduction Posterity may remember Gertrude Stein only for ‘A rose is a rose is a rose’. The mean- ing behind this apparently meaningless statement, she said, was that a thing is what it is, the name invoking the images and emotions associated with it. One of the most cele- brated lines in twentieth-century poetry, it highlights the importance of names by a sim- ple process of repetition. -

From the Bohol Sea, the Philippines

THE RAFFLES BULLETIN OF ZOOLOGY 2008 RAFFLES BULLETIN OF ZOOLOGY 2008 56(2): 385–404 Date of Publication: 31 Aug.2008 © National University of Singapore NEW GENERA AND SPECIES OF EUXANTHINE CRABS (CRUSTACEA: DECAPODA: BRACHYURA: XANTHIDAE) FROM THE BOHOL SEA, THE PHILIPPINES Jose Christopher E. Mendoza Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, 14 Science Drive 4, Singapore 117543; Institute of Biology, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, 1101, Philippines Email: [email protected] Peter K. L. Ng Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, 14 Science Drive 4, Singapore 117543, Republic of Singapore Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT. – Two new genera and four new xanthid crab species belonging to the subfamily Euxanthinae Alcock (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura) are described from the Bohol Sea, central Philippines. Rizalthus, new genus, with just one species, R. anconis, new species, can be distinguished from allied genera by characters of the carapace, epistome, chelipeds, male abdomen and male fi rst gonopod. Visayax, new genus, contains two new species, V. osteodictyon and V. estampadori, and can be distinguished from similar genera using a combination of features of the carapace, epistome, thoracic sternum, male abdomen, pereiopods and male fi rst gonopod. A new species of Hepatoporus Serène, H. pumex, is also described. It is distinguished from congeners by the unique morphology of its front, carapace sculpturing, form of the subhepatic cavity and structure of the male fi rst gonopod. KEY WORDS. – Crustacea, Xanthidae, Euxanthinae, Rizalthus, Visayax, Hepatoporus, Panglao 2004, the Philippines. INTRODUCTION & Jeng, 2006; Anker et al., 2006; Dworschak, 2006; Marin & Chan, 2006; Ahyong & Ng, 2007; Anker & Dworschak, There are currently 24 genera and 83 species in the xanthid 2007; Manuel-Santos & Ng, 2007; Mendoza & Ng, 2007; crab subfamily Euxanthinae worldwide, with most occurring Ng & Castro, 2007; Ng & Manuel-Santos, 2007; Ng & in the Indo-Pacifi c (Ng & McLay, 2007; Ng et al., 2008). -

Order GASTEROSTEIFORMES PEGASIDAE Eurypegasus Draconis

click for previous page 2262 Bony Fishes Order GASTEROSTEIFORMES PEGASIDAE Seamoths (seadragons) by T.W. Pietsch and W.A. Palsson iagnostic characters: Small fishes (to 18 cm total length); body depressed, completely encased in Dfused dermal plates; tail encircled by 8 to 14 laterally articulating, or fused, bony rings. Nasal bones elongate, fused, forming a rostrum; mouth inferior. Gill opening restricted to a small hole on dorsolat- eral surface behind head. Spinous dorsal fin absent; soft dorsal and anal fins each with 5 rays, placed posteriorly on body. Caudal fin with 8 unbranched rays. Pectoral fins large, wing-like, inserted horizon- tally, composed of 9 to 19 unbranched, soft or spinous-soft rays; pectoral-fin rays interconnected by broad, transparent membranes. Pelvic fins thoracic, tentacle-like,withI spine and 2 or 3 unbranched soft rays. Colour: in life highly variable, apparently capable of rapid colour change to match substrata; head and body light to dark brown, olive-brown, reddish brown, or almost black, with dorsal and lateral surfaces usually darker than ventral surface; dorsal and lateral body surface often with fine, dark brown reticulations or mottled lines, sometimes with irregular white or yellow blotches; tail rings often encircled with dark brown bands; pectoral fins with broad white outer margin and small brown spots forming irregular, longitudinal bands; unpaired fins with small brown spots in irregular rows. dorsal view lateral view Habitat, biology, and fisheries: Benthic, found on sand, gravel, shell-rubble, or muddy bottoms. Collected incidentally by seine, trawl, dredge, or shrimp nets; postlarvae have been taken at surface lights at night. -

Colonisation of the Mariana Islands: New Evidence and Implications for Human Movements V 479

1 New evidence and implications ' for human movements in the Western Pacific John L. Craib Archaeologist Introduction Within the last five years, archaeological investigations on Saipan, ?inian and Guam has changed our understanding of the early period of human occupation in the Mariana Islands (Figure l). This work has not only extended the antiquity of human presence in these islands, it has provided a more detailed sample of the cultural assemblage asso- ciated with this early settlement. While increasing our knowledge of the prehistory of the Marianas, these new data, at the same time, offer important implications for human movement in the western Pacific. This paper provides a brief overview of recent fin- dings and discusses possible origins of the founding population in the Marianas and the implications this has for general movement within the western Pacific. Early sites in the Mariana Islands Two sites on Saipan, Chalan Piao and Achugao, are now dated to between 3000- 3600 cal BP; the calibrated age range at Unai Chulu, on Tinian, straddles 3000 BP. The assemblage recovered from these three sites include finely made pottery, much of it red- 478 V Le Pacifique de 5000 A 2000 avant le present /The Pacific from 5000 to 2000 BP I Figure 1 Mariana Islands in the Western Pacific. J. L. CRAIB- Colonisation of the Mariana Islands: New evidence and implications for human movements V 479 slipped, with a small percentage of sherds exhibiting finely incised and stamped deco- rations. Also presents in these deposits are a variety of shell ornaments manufactured almost entirely from Conus spp. -

View on KKMP This Morning

Super Typhoon Yutu Relief & Recovery Update #4 POST-DECLARATION DAMAGE ASSESSMENT COMPLETED; RELIEF MANPOWER ON-ISLAND READY TO SUPPORT; FEEDER 1, PARTIAL 1 & 2 BACK ONLINE Release Date: October 29, 2018 On Sunday, October 28, 2018, CNMI Leadership and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) conducted a Post-Declaration Damage Assessment. Saipan, Tinian and Rota experienced very heavy rainfall and extremely high winds which caused damages to homes, businesses and critical infrastructure. Utility infrastructure on all three islands has been visibly severely impacted to include downed power lines, transformers and poles. Driving conditions remain hazardous as debris removal operations are still underway. At the request of Governor Ralph DLG. Torres, representatives from FEMA Individual Assistance (IA) and the US Small Business Administration (SBA) joined the CNMI on an Aerial Preliminary Damage Assessment of Saipan, Tinian and Rota. Findings are as follows: SAIPAN: 317 Major; 462 Destroyed (T=779) Villages covered: Kagman 1, 2 & 3 and LauLau, Susupe, Chalan Kanoa, San Antonio, Koblerville, Dandan and San Vicente Power outage across the island 2-mile-long gas lines observed Extensive damage to critical infrastructure in southern Saipan Downed power poles and lines Page 1 of 8 Page printed at fema.gov/ja/press-release/20201016/super-typhoon-yutu-relief-recovery-update-4-post-declaration- 09/28/2021 damage TINIAN: 113 Major; 70 Destroyed (T=183) Villages covered: San Jose & House of Taga, Carolinas, Marpo Valley and Marpo Heights Power outage across the island; estimated to take 3 months to achieve 50% restoration Tinian Health Center sustained extensive damage Observed a downed communications tower ROTA: 38 Major; 13 Destroyed (T=51) Villages covered: Songsong Village and Sinapalo Power outage across the island Sustained the least amount of damage as compared to Saipan and Tinian Red Cross CNMI-wide assessments begin Tuesday, October 30, 2018. -

Minutes of Discussions

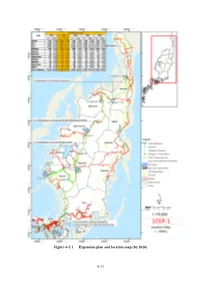

Figure 6-5.1 Expansion plan and location map (by 2020) 6-31 NGARCHELONG STATE アルコロン州 (Ollei) (Ngebei) 2.1km (Oketol) (Ngerbau) 0.9km 1.8km (Ngrill) 1.0km NGARAARD STATE ガラルド州 (Chol School) 1.0km (Urrung) 3.6km (Chelab) NGAREMLENGUI STATE NGARDMAU STATE (Ngerderemang) ガラスマオ州 1.0km アルモノグイ州 3φTr 6MW 750kVA x 1 34.5/13.8kV NGARAARD-2 S/S NGARAARD-1 S/S (Ngkeklau) 3.6km 1φTr 3x25kVA 34.5/13.8kV Busstop(Junction)-Ngardmau: 24.4km Ngardmau-Ngaraard-2: 11.8km ASAHI S/S (Ngermetengel) NGARDMAU NGIWAL STATE S/S 2.9km オギワ-ル州 3φTr 1x300kVA 34.5/13.8kV (Ogill) 1φTr 3x75kVA 34.5/13.8kV NGATPANG STATEガスパン州 IBOBANG S/S (Ngetpang Elementary School) (Ibobang) 2.0km (Ngerutoi) (Dock) (Ngetbong Ice Box) 1φTr 3x75kVA 34.5/13.8kV MELEKEOK STATE メレケオク州 AIMELIIK STATE 8.25km アイメリ-ク州 Busstop NEKKENG S/S (Junction) KOKUSAI S/S 8.8km (Ngeruling) (Oisca) 1φTr 3x75kVA 4MW 34.5/13.8kV AIMELIIK-2 S/S 3φTr 1x5MVA 6.5km 1.2km AIMELIIK-1 S/S 34.5/13.8kV (Community Center) 1φTr 3x75kVA NGCHESAR STATE 1.5km 34.5/13.8kV Busstop(Junction) – チェサ-ル州 3φTr Airai 9.0Km 1x1000kVA 34.5/13.8kV (Rai) (ELECHUI) (AIMELIIK) AIRAI S/S AIMELIIK POWER STATION アイメリ-ク発電所 N10 AIRAI STATE No.1 Tr No.2 Tr 10MVA 10MVA アイライ州 34.5/13.8kV 34.5/13.8kV 3φTr 10MVA 34.5/13.8kV (Airai State) N10 G G 6MW M6 M7 (Airport) 5MW 5MW (Mitsubishi) 15km 13.98km BABELDAOB ISLAND バベルダオブ島 K-B Bridge KOROR ISLAND コロ-ル島 Koror S/S LEGEND 凡例 3φTr PV System 10MVA 太陽光発電設備 34.5/13.8kV GENERATOR G 発電機 Malakal – Airai 9.2Km TRANSFORMER 変圧器 DISCONNECTING SWITCH 断路器 (Hechang) (Koror) LOAD BREAKER SWITCH 負荷開閉器 CIRCUIT BREAKER