Vermonters and the Lower Canadian Rebellions of 1837-1838*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

900 History, Geography, and Auxiliary Disciplines

900 900 History, geography, and auxiliary disciplines Class here social situations and conditions; general political history; military, diplomatic, political, economic, social, welfare aspects of specific wars Class interdisciplinary works on ancient world, on specific continents, countries, localities in 930–990. Class history and geographic treatment of a specific subject with the subject, plus notation 09 from Table 1, e.g., history and geographic treatment of natural sciences 509, of economic situations and conditions 330.9, of purely political situations and conditions 320.9, history of military science 355.009 See also 303.49 for future history (projected events other than travel) See Manual at 900 SUMMARY 900.1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901–909 Standard subdivisions of history, collected accounts of events, world history 910 Geography and travel 920 Biography, genealogy, insignia 930 History of ancient world to ca. 499 940 History of Europe 950 History of Asia 960 History of Africa 970 History of North America 980 History of South America 990 History of Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds .1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901 Philosophy and theory of history 902 Miscellany of history .2 Illustrations, models, miniatures Do not use for maps, plans, diagrams; class in 911 903 Dictionaries, encyclopedias, concordances of history 901 904 Dewey Decimal Classification 904 904 Collected accounts of events Including events of natural origin; events induced by human activity Class here adventure Class collections limited to a specific period, collections limited to a specific area or region but not limited by continent, country, locality in 909; class travel in 910; class collections limited to a specific continent, country, locality in 930–990. -

OECD/IMHE Project Self Evaluation Report: Atlantic Canada, Canada

OECD/IMHE Project Supporting the Contribution of Higher Education Institutions to Regional Development Self Evaluation Report: Atlantic Canada, Canada Wade Locke (Memorial University), Elizabeth Beale (Atlantic Provinces Economic Council), Robert Greenwood (Harris Centre, Memorial University), Cyril Farrell (Atlantic Provinces Community College Consortium), Stephen Tomblin (Memorial University), Pierre-Marcel Dejardins (Université de Moncton), Frank Strain (Mount Allison University), and Godfrey Baldacchino (University of Prince Edward Island) December 2006 (Revised March 2007) ii Acknowledgements This self-evaluation report addresses the contribution of higher education institutions (HEIs) to the development of the Atlantic region of Canada. This study was undertaken following the decision of a broad group of partners in Atlantic Canada to join the OECD/IMHE project “Supporting the Contribution of Higher Education Institutions to Regional Development”. Atlantic Canada was one of the last regions, and the only North American region, to enter into this project. It is also one of the largest groups of partners to participate in this OECD project, with engagement from the federal government; four provincial governments, all with separate responsibility for higher education; 17 publicly funded universities; all colleges in the region; and a range of other partners in economic development. As such, it must be appreciated that this report represents a major undertaking in a very short period of time. A research process was put in place to facilitate the completion of this self-evaluation report. The process was multifaceted and consultative in nature, drawing on current data, direct input from HEIs and the perspectives of a broad array of stakeholders across the region. An extensive effort was undertaken to ensure that input was received from all key stakeholders, through surveys completed by HEIs, one-on-one interviews conducted with government officials and focus groups conducted in each province which included a high level of private sector participation. -

GOLD PLACER DEPOSITS of the EASTERN TOWNSHIPS, PART E PROVINCE of QUEBEC, CANADA Department of Mines and Fisheries Honourable ONESIME GAGNON, Minister L.-A

RASM 1935-E(A) GOLD PLACER DEPOSITS OF THE EASTERN TOWNSHIPS, PART E PROVINCE OF QUEBEC, CANADA Department of Mines and Fisheries Honourable ONESIME GAGNON, Minister L.-A. RICHARD. Deputy-Minister BUREAU OF MINES A.-0. DUFRESNE, Director ANNUAL REPORT of the QUEBEC BUREAU OF MINES for the year 1935 JOHN A. DRESSER, Directing Geologist PART E Gold Placer Deposits of the Eastern Townships by H. W. McGerrigle QUEBEC REDEMPTI PARADIS PRINTER TO HIS MAJESTY THE KING 1936 PROVINCE OF QUEBEC, CANADA Department of Mines and Fisheries Honourable ONESIME GAGNON. Minister L.-A. RICHARD. Deputy-Minister BUREAU OF MINES A.-O. DUFRESNE. Director ANNUAL REPORT of the QUEBEC BUREAU OF MINES for the year 1935 JOHN A. DRESSER, Directing Geologist PART E Gold Placer Deposits of the Eastern Townships by H. W. MeGerrigle QUEBEe RÉDEMPTI PARADIS • PRINTER TO HIS MAJESTY THE KING 1936 GOLD PLACER DEPOSITS OF THE EASTERN TOWNSHIPS by H. W. McGerrigle TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 5 Scope of report and method of work 5 Acknowledgments 6 Summary 6 Previous work . 7 Bibliography 9 DESCRIPTION OF PLACER LOCALITIES 11 Ascot township 11 Felton brook 12 Grass Island brook . 13 Auckland township. 18 Bury township .. 19 Ditton area . 20 General 20 Summary of topography and geology . 20 Table of formations 21 IIistory of development and production 21 Dudswell township . 23 Hatley township . 23 Horton township. 24 Ireland township. 25 Lamhton township . 26 Leeds township . 29 Magog township . 29 Orford township . 29 Shipton township 31 Moe and adjacent rivers 33 Moe river . 33 Victoria river 36 Stoke Mountain area . -

THE SPECIAL COUNCILS of LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 By

“LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL EST MORT, VIVE LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL!” THE SPECIAL COUNCILS OF LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 by Maxime Dagenais Dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the PhD degree in History. Department of History Faculty of Arts Université d’Ottawa\ University of Ottawa © Maxime Dagenais, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 ii ABSTRACT “LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL EST MORT, VIVE LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL!” THE SPECIAL COUNCILS OF LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 Maxime Dagenais Supervisor: University of Ottawa, 2011 Professor Peter Bischoff Although the 1837-38 Rebellions and the Union of the Canadas have received much attention from historians, the Special Council—a political body that bridged two constitutions—remains largely unexplored in comparison. This dissertation considers its time as the legislature of Lower Canada. More specifically, it examines its social, political and economic impact on the colony and its inhabitants. Based on the works of previous historians and on various primary sources, this dissertation first demonstrates that the Special Council proved to be very important to Lower Canada, but more specifically, to British merchants and Tories. After years of frustration for this group, the era of the Special Council represented what could be called a “catching up” period regarding their social, commercial and economic interests in the colony. This first section ends with an evaluation of the legacy of the Special Council, and posits the theory that the period was revolutionary as it produced several ordinances that changed the colony’s social, economic and political culture This first section will also set the stage for the most important matter considered in this dissertation as it emphasizes the Special Council’s authoritarianism. -

Eight History Lessons Grade 8

Eight History Lessons Grade 8 Submitted By: Rebecca Neadow 05952401 Submitted To: Ted Christou CURR 355 Submitted On: November 15, 2013 INTRODUCTORY ACTIVITY OVERVIEW This is an introductory assignment for students in a grade 8 history class dealing with the Red River Settlement. LEARNING GOAL AND FOCUSING QUESTION - During this lesson students activate their prior knowledge and connections to gain a deeper understanding of the word Rebellion and what requires to set up a new settlement. CURRICULUM EXPECTATIONS - Interpret and analyse information and evidence relevant to their investigations, using a variety of tools. MATERIALS - There are certain terms students will need to understand within this lesson. They are: 1. Emigrate – to leave one place or country in order to settle in another 2. Lord Selkirk – Scottish born 5th Earl of Selkirk, used his money to buy the Hudson’s Bay Company in order to get land to establish a settlement on the Red River in Rupert’s Land in 1812 3. Red River – a river that flows North Dakota north into Lake Winnipeg 4. Exonerate – to clear or absolve from blame or a criminal charge 5. Hudson’s Bay Company – an English company chartered in 1670 to trade in all parts of North America drained by rivers flowing into Hudson’s Bay 6. North West Company – a fur trading business headquartered in Montréal from 1779 to 1821 which competed, often violently, with the Hudson’s Bay Company until it merged with the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1821 7. Rupert’s Land – the territories granted by Charles II of England to the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1670 and ceded to the Canadian government in 1870 - For research: textbook, computer, dictionaries or whatever you have available to you. -

Chapter 1: Introduction

AN ANALYSIS OF THE 1875-1877 SCARLET FEVER EPIDEMIC OF CAPE BRETON ISLAND, NOVA SCOTIA ___________________________________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia ___________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________________________ by JOSEPH MACLEAN PARISH Dr. Lisa Sattenspiel, Dissertation Supervisor DECEMBER 2004 © Copyright by Joseph MacLean Parish 2004 All Rights Reserved Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the people of Cape Breton and in particular the people of Chéticamp, both past and present. Your enduring spirits, your pioneering efforts and your selfless approach to life stand out amongst all peoples. Without these qualities in you and your ancestors, none of this would have been possible. Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my fiancée Demmarest who has been a constant source of support throughout the process of creating this dissertation and endured my stress with me every step of the way. I will never forget your patience and selflessness. My mother Ginny was a steady source of encouragement and strength since my arrival in Missouri so shortly after the passing of my father. Your love knows no bounds mom. I would also like to thank my close friends who have believed in me throughout my entire academic “career” and supported my choices including, in no particular order, Mickey ‘G’, Alexis Dolphin, Rhonda Bathurst, Michael Pierce, Jason Organ and Ahmed Abu-Dalou. I owe special thanks to my aunt and uncle, Muriel and Earl “Curly” Gray of Sydney, Nova Scotia, and my cousins Wallace, Carole, Crystal and Michelle AuCoin and Auguste Deveaux of Chéticamp, Nova Scotia for being my gracious hosts numerous times throughout the years of my research. -

THE ECONOMY of CANADA in the NINETEENTH CENTURY Marvin Mcinnis

2 THE ECONOMY OF CANADA IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY marvin mcinnis FOUNDATIONS OF THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY CANADIAN ECONOMY For the economy of Canada it can be said that the nineteenth century came to an end in the mid-1890s. There is wide agreement among observers that a fundamental break occurred at about that time and that in the years thereafter Canadian economic development, industrialization, population growth, and territorial expansion quickened markedly. This has led economic historians to put a special emphasis on the particularly rapid economic expansion that occurred in the years after about 1896. That emphasis has been deceptive and has generated a perception that little of consequence was happening before 1896. W. W. Rostow was only reflecting a reasonable reading of what had been written about Canadian economic history when he declared the “take-off” in Canada to have occurred in the years between 1896 and 1913. That was undoubtedly a period of rapid growth and great transformation in the Canadian economy and is best considered as part of the twentieth-century experience. The break is usually thought to have occurred in the mid-1890s, but the most indicative data concerning the end of this period are drawn from the 1891 decennial census. By the time of the next census in 1901, major changes had begun to occur. It fits the available evidence best, then, to think of an early 1890s end to the nineteenth century. Some guidance to our reconsideration of Canadian economic devel- opment prior to the big discontinuity of the 1890s may be given by a brief review of what had been accomplished by the early years of that decade. -

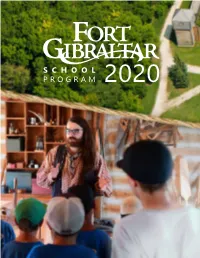

S C H O O L Program

SCHOOL PROGRAM 2020 INTRODUCTION We invite you to learn about Fort Gibraltar’s influence over the cultural development of the Red River settlement. Delve into the lore of the French Canadian voyageurs who paddled across the country, transporting trade-goods and the unique customs of Lower Canada into the West. They married into the First Nations communities and precipitated the birth of the Métis nation, a unique culture that would have a lasting impact on the settlement. Learn how the First Nations helped to ensure the success of these traders by trapping the furs needed for the growing European marketplace. Discover how they shared their knowledge of the land and climate for the survival of their new guests. On the other end of the social scale, meet one of the upper-class managers of the trading post. Here you will get a glimpse of the social conventions of a rapidly changing industrialized Europe. Through hands-on demonstrations and authentic crafts, learn about the formation of this unique community nearly two hundred years ago. Costumed interpreters will guide your class back in time to the year 1815 to a time of immeasurable change in the Red River valley. 2 GENERAL INFORMATION Fort Gibraltar Admission 866, Saint-Joseph St. Guided Tour Managed by: Festival du Voyageur inc. School Groups – $5 per student Phone: 204.237.7692 Max. 80 students, 1.877.889.7692 Free admission for teachers Fax: 204.233.7576 www.fortgibraltar.com www.heho.ca Dates of operation for the School Program Reservations May 11 to June 26, 2019 Guided tours must be booked at least one week before your outing date. -

AC Buchanan and the Megantic Experiment

A. C. Buchanan and the Megantic Experiment: Promoting British Colonization in Lower Canada J. I. LITTLE* Between 1829 and 1832 a British settler colony was established on the northern fringe of Lower Canada’s Eastern Townships, in what became known as Megantic county. The main aim of the chief instigator and manager of the project, “emigrant” agent A. C. Buchanan, was to demonstrate the viability of state-assisted “pauper” colonization, as long advocated by Colonial Under- Secretary Robert Wilmot-Horton. Buchanan’s project was successful insofar as he convinced over 5,300 immigrants, the majority of whom were Irish Protestants, to follow the Craig and Gosford roads to the uninhabited northern foothills of the Appalachians. But the British government failed to apply this “experiment” elsewhere in Lower or Upper Canada, and the British settler community did not expand far beyond the townships of Leeds, Inverness, and Ireland because of their isolation from external markets. Instead, French-Canadian settlers moved into the surrounding townships, with the result that the British-origin population became a culturally isolated island of interrelated families that slowly disappeared due to out-migration. De 1829 à 1832, une colonie de peuplement britannique a vu le jour au Bas- Canada, en périphérie nord des cantons de l’Est, dans ce qui deviendra le comté de Mégantic. L’instigateur et chef du projet, l’agent d’émigration A. C. Buchanan, avait pour objectif premier de prouver la viabilité, avec le soutien de l’État, de la colonisation par les « pauvres » que préconisait depuis longtemps le sous- secrétaire aux Colonies Robert Wilmot-Horton. -

Potton Heritage Association the Trouble In

VOLUME 6 – NUMÉRO 2 – AUTOMNE 2018 | TIRÉ À PART HISTOIRE POTTON HISTORY Canada found eager sympathizers among the The Trouble in Potton “Sons of Liberty” on both sides of the border, By Audrey Martin McCaw and Potton Township was dismayed to find itself uncomfortably close to the centre of the Yesterdays of Brome County – Volume Four, storm. Daily alarms kept the populace in a The Brome County Historical Society, state of panic: dispatch riders were shot at, Knowlton, Quebec 1980, pages 28-36 worshippers gathering at the Potton school house for their Sunday service were shocked It is 150 years since sparks from the Papineau to find a cache of gunpowder hidden in the Rebellion flared into scattered eruptions and ashes of the stove. Challenges for the hastily short-lived battles in south-western Quebec. formed Potton Guard came to a head on the When students of Canadian history think of evening of February 27th, 1838, a date which “the troubles of 1837-38”, they are apt to E. C. Bamett said: “must go down in history in recall the confrontations between the rebels, red letter.” or “patriotes” and government forces at St. Charles and St. Denis on the Richelieu River But first, some background. In 1837, many of east of Montreal, the rout at St. Eustache and the inhabitants of Potton were sons and the Battle of Moore's Corners in Missisquoi daughters of original settlers from the U.S. County. However, here in Brome County who had been loyal to the Crown during the feelings reached a fever pitch too and there American Revolution, and they inherited the was the odd skirmish that might very well political sympathies of their parents. -

The Origins of Millerite Separatism

The Origins of Millerite Separatism By Andrew Taylor (BA in History, Aurora University and MA in History, University of Rhode Island) CHAPTER 1 HISTORIANS AND MILLERITE SEPARATISM ===================================== Early in 1841, Truman Hendryx moved to Bradford, Pennsylvania, where he quickly grew alienated from his local church. Upon settling down in his new home, Hendryx attended several services in his new community’s Baptist church. After only a handful of visits, though, he became convinced that the church did not believe in what he referred to as “Bible religion.” Its “impiety” led him to lament, “I sometimes almost feel to use the language [of] the Prophecy ‘Lord, they have killed thy prophets and digged [sic] down thine [sic] altars and I only am left alone and they seek my life.”’1 His opposition to the church left him isolated in his community, but his fear of “degeneracy in the churches and ministers” was greater than his loneliness. Self-righteously believing that his beliefs were the “Bible truth,” he resolved to remain apart from the Baptist church rather than attend and be corrupted by its “sinful” influence.2 The “sinful” church from which Hendryx separated himself was characteristic of mainstream antebellum evangelicalism. The tumultuous first decades of the nineteenth century had transformed the theological and institutional foundations of mainstream American Protestantism. During the colonial era, American Protestantism had been dominated by the Congregational, Presbyterian, and Anglican churches, which, for the most part, had remained committed to the theology of John Calvin. In Calvinism, God was envisioned as all-powerful, having predetermined both the course of history and the eternal destiny of all humans. -

La Bataille De Saint-Denis

L A S É R I E D E S B A T A I L L E S C A N A D I E N N E S La bataille de Saint-Denis par Elinor Kyte Senior L A S É R I E D E S B A T A I L L E S C A N A D I E N N E S La bataille de Saint-Denis L A S É R I E D E S B A T A I L L E S C A N A D I E N N E S La bataille de Saint-Denis par Elinor Kyte Senior Musée canadien de la guerre La série des batailles canadiennes no 7 BALMUIR Musée canadien de la guerre BOOK PUBLISHING LTD. ©1990 MUSÉE CANADIEN DE LA GUERRE Balmuir Book Publishing Limited C.P. 160, Succursale postale B Toronto (Ontario) M5T 2T3 ISBN 0-919511-45-7 L A S É R I E D E S B A T A I L L E S C A N A D I E N N E S Au fil de son histoire, le Canada a vécu des moments fort difficiles, des luttes d'une envergure variable mais qui eurent toutes un effet marquant sur le développement du pays et qui ont modifié ou reflété le caractère de son peuple. La série présentée par le Musée canadien de la guerre décrit ces batailles et événements au moyen de narrations faites par des historiens dûment qualifiés et rehaussées par des documents visuels complétant très bien le texte.