The 1837-1838 Rebellions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

900 History, Geography, and Auxiliary Disciplines

900 900 History, geography, and auxiliary disciplines Class here social situations and conditions; general political history; military, diplomatic, political, economic, social, welfare aspects of specific wars Class interdisciplinary works on ancient world, on specific continents, countries, localities in 930–990. Class history and geographic treatment of a specific subject with the subject, plus notation 09 from Table 1, e.g., history and geographic treatment of natural sciences 509, of economic situations and conditions 330.9, of purely political situations and conditions 320.9, history of military science 355.009 See also 303.49 for future history (projected events other than travel) See Manual at 900 SUMMARY 900.1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901–909 Standard subdivisions of history, collected accounts of events, world history 910 Geography and travel 920 Biography, genealogy, insignia 930 History of ancient world to ca. 499 940 History of Europe 950 History of Asia 960 History of Africa 970 History of North America 980 History of South America 990 History of Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds .1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901 Philosophy and theory of history 902 Miscellany of history .2 Illustrations, models, miniatures Do not use for maps, plans, diagrams; class in 911 903 Dictionaries, encyclopedias, concordances of history 901 904 Dewey Decimal Classification 904 904 Collected accounts of events Including events of natural origin; events induced by human activity Class here adventure Class collections limited to a specific period, collections limited to a specific area or region but not limited by continent, country, locality in 909; class travel in 910; class collections limited to a specific continent, country, locality in 930–990. -

THE SPECIAL COUNCILS of LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 By

“LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL EST MORT, VIVE LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL!” THE SPECIAL COUNCILS OF LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 by Maxime Dagenais Dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the PhD degree in History. Department of History Faculty of Arts Université d’Ottawa\ University of Ottawa © Maxime Dagenais, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 ii ABSTRACT “LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL EST MORT, VIVE LE CONSEIL SPÉCIAL!” THE SPECIAL COUNCILS OF LOWER CANADA, 1838-1841 Maxime Dagenais Supervisor: University of Ottawa, 2011 Professor Peter Bischoff Although the 1837-38 Rebellions and the Union of the Canadas have received much attention from historians, the Special Council—a political body that bridged two constitutions—remains largely unexplored in comparison. This dissertation considers its time as the legislature of Lower Canada. More specifically, it examines its social, political and economic impact on the colony and its inhabitants. Based on the works of previous historians and on various primary sources, this dissertation first demonstrates that the Special Council proved to be very important to Lower Canada, but more specifically, to British merchants and Tories. After years of frustration for this group, the era of the Special Council represented what could be called a “catching up” period regarding their social, commercial and economic interests in the colony. This first section ends with an evaluation of the legacy of the Special Council, and posits the theory that the period was revolutionary as it produced several ordinances that changed the colony’s social, economic and political culture This first section will also set the stage for the most important matter considered in this dissertation as it emphasizes the Special Council’s authoritarianism. -

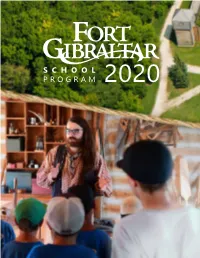

S C H O O L Program

SCHOOL PROGRAM 2020 INTRODUCTION We invite you to learn about Fort Gibraltar’s influence over the cultural development of the Red River settlement. Delve into the lore of the French Canadian voyageurs who paddled across the country, transporting trade-goods and the unique customs of Lower Canada into the West. They married into the First Nations communities and precipitated the birth of the Métis nation, a unique culture that would have a lasting impact on the settlement. Learn how the First Nations helped to ensure the success of these traders by trapping the furs needed for the growing European marketplace. Discover how they shared their knowledge of the land and climate for the survival of their new guests. On the other end of the social scale, meet one of the upper-class managers of the trading post. Here you will get a glimpse of the social conventions of a rapidly changing industrialized Europe. Through hands-on demonstrations and authentic crafts, learn about the formation of this unique community nearly two hundred years ago. Costumed interpreters will guide your class back in time to the year 1815 to a time of immeasurable change in the Red River valley. 2 GENERAL INFORMATION Fort Gibraltar Admission 866, Saint-Joseph St. Guided Tour Managed by: Festival du Voyageur inc. School Groups – $5 per student Phone: 204.237.7692 Max. 80 students, 1.877.889.7692 Free admission for teachers Fax: 204.233.7576 www.fortgibraltar.com www.heho.ca Dates of operation for the School Program Reservations May 11 to June 26, 2019 Guided tours must be booked at least one week before your outing date. -

York Region Heritage Directory Resources and Contacts 2011 Edition

York Region Heritage Directory Resources and Contacts 2011 edition The Regional Municipality of York 17250 Yonge Street Newmarket, ON L3Y 6Z1 Tel: (905)830-4444 Fax: (905)895-3031 Internet: http://www.york.ca Disclaimer This directory was compiled using information provided by the contacted organization, and is provided for reference and convenience. The Region makes no guarantees or warranties as to the accuracy of the information. Additions and Corrections If you would like to correct or add information to future editions of this document, please contact the Supervisor, Corporate Records & Information, Office of the Regional Clerk, Regional Municipality of York or by phone at (905)830-4444 or toll- free 1-877-464-9675. A great debt of thanks is owed for this edition to Lindsay Moffatt, Research Assistant. 2 Table of Contents Page No. RESOURCES BY TYPE Archives ……………………………………………………………..… 5 Historical/Heritage Societies ……………………………… 10 Libraries ……………………………………………………………… 17 Museums ………………………………………………………………21 RESOURCES BY LOCATION Aurora …………………………………………………………………. 26 East Gwillimbury ………………………………………………… 28 Georgina …………………………………………………………….. 30 King …………………………………………………………………….. 31 Markham …………………………………………………………….. 34 Newmarket …………………………………………………………. 37 Richmond Hill ……………………………………………………… 40 Vaughan …………………………………………………………….. 42 Whitchurch-Stouffville ……………………………………….. 46 PIONEER CEMETERIES ………..…………..………………….. 47 Listed alphabetically by Local Municipality. RESOURCES OUTSIDE YORK REGION …………….…… 62 HELPFUL WEBSITES ……………………………………………… 64 INDEX…………………………………………………………………….. 66 3 4 ARCHIVES Canadian Quaker Archives at Pickering College Website: http://www.pickeringcollege.on.ca Email: [email protected] Phone: 905-895-1700 Address: 16945 Bayview Ave., Newmarket, ON, L3Y 4X2 Description: The Canadian Quaker Archives of the Canadian Yearly Meetings of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) is housed at Pickering College in Newmarket. The records of Friends’ Monthly and Yearly Meetings in Canada are housed here. -

Conflict & Challenges

Conflict & Challenges Grade 7 Written by Eleanor M. Summers & Ruth Solski This history series was developed to make history curriculum accessible to students at multiple skill levels and with various learning styles. The content covers key topics required for seventh grade history and supports the updated 2013 Ontario Curriculum: History Grade 7. Each topic is presented in a clear, concise manner, which makes the information accessible to struggling learners, but is also appropriate for students performing at or above grade level. Illustrations, maps, and diagrams visually enhance each topic covered and provide support for visual learners. The reading passages focus on the significant people, historic events, and changes in the government that were important to Canadian history between 1800 and 1850, giving students a good overall understanding of this time period. Eleanor Summers is a retired Ruth Solski was an educator for elementary teacher who 30 years, and has created many continues to be involved in teaching resources. As a writer, various levels of education. Her her goal is to provide teachers goal is to write creative and with a useful tool that they can practical resources for teachers use in their classrooms to bring to use in their literacy programs. the joy of learning to children. Copyright © On The Mark Press 2014 This publication may be reproduced under licence from Access Copyright, or with the express written permission of On The Mark Press, or as permitted by law. All rights are otherwise reserved, and no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, scanning, recording or otherwise, except as specifically authorized. -

The Perilous Escape of William Lyon Mackenzie December 7 to 11, 1837 Christopher Raible

Document generated on 09/26/2021 7:53 a.m. Ontario History “A journey undertaken under peculiar circumstances” The Perilous Escape of William Lyon Mackenzie December 7 to 11, 1837 Christopher Raible Volume 108, Number 2, Fall 2016 Article abstract When his 1837 Upper Canada Rebellion came to a sudden end with the routing URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1050592ar of rebels at Montgomery’s Tavern on 7 December, William Lyon Mackenzie DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1050592ar was forced to run for his life. With a price on his head, travelling mostly by night—west toward the Niagara Escarpment, south around the end of Lake See table of contents Ontario and then east across the Niagara peninsula—the rebel leader made his way from a village north of Toronto to safety across the Niagara River in the United States. His journey of more than 150 miles took five days ( four nights) Publisher(s) on foot, on horseback, and on wagon or sleigh, was aided by more than thirty different individuals and families. At great personal risk, they fed him, nursed The Ontario Historical Society him, hid him, advised him, accompanied him. This article maps Mackenzie’s exact route, identifies those who helped him, and reflects on the natural ISSN hazards and human perils he encountered. 0030-2953 (print) 2371-4654 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Raible, C. (2016). “A journey undertaken under peculiar circumstances”: The Perilous Escape of William Lyon Mackenzie December 7 to 11, 1837. Ontario History, 108(2), 131–155. https://doi.org/10.7202/1050592ar Copyright © The Ontario Historical Society, 2016 This document is protected by copyright law. -

Healey's "From Quaker to Upper Canadian: Faith and Community Among Yonge Street Friends" - Book Review Thomas D

Quaker Studies Volume 12 | Issue 2 Article 10 2008 Healey's "From Quaker to Upper Canadian: Faith and Community among Yonge Street Friends" - Book Review Thomas D. Hamm Earlham College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/quakerstudies Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Hamm, Thomas D. (2008) "Healey's "From Quaker to Upper Canadian: Faith and Community among Yonge Street Friends" - Book Review," Quaker Studies: Vol. 12: Iss. 2, Article 10. Available at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/quakerstudies/vol12/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quaker Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEWS 269 HEALEY, Robynne Rogers, From Quaker to Upper Canadian: Faith and Community among Yonge Street Friends, 1801-1850 (Montreal and Kingston: MeGill-Queen's University Press, 2006), pp. xxvi + 292, including maps, charts, tables and illustra tions. ISBN 9-78077-35313-69, Hardback, $75, £56. Robynne Rogers Healey has written one of the most useful and important studies of the evolution of a Quaker community ever published. Several historians, myself included, have ventured broad overviews of how and why Quakerism changed in the nineteenth century. But now we have a careful, incisive analysis of those changes at the local level. Healey's subject is Yonge Street Monthly Meeting in Ontario. Shortly after 1800, Friends from Vermont and Pennsylvania took advantage of generous land grants to settle north of what would become Toronto. -

Potton Heritage Association the Trouble In

VOLUME 6 – NUMÉRO 2 – AUTOMNE 2018 | TIRÉ À PART HISTOIRE POTTON HISTORY Canada found eager sympathizers among the The Trouble in Potton “Sons of Liberty” on both sides of the border, By Audrey Martin McCaw and Potton Township was dismayed to find itself uncomfortably close to the centre of the Yesterdays of Brome County – Volume Four, storm. Daily alarms kept the populace in a The Brome County Historical Society, state of panic: dispatch riders were shot at, Knowlton, Quebec 1980, pages 28-36 worshippers gathering at the Potton school house for their Sunday service were shocked It is 150 years since sparks from the Papineau to find a cache of gunpowder hidden in the Rebellion flared into scattered eruptions and ashes of the stove. Challenges for the hastily short-lived battles in south-western Quebec. formed Potton Guard came to a head on the When students of Canadian history think of evening of February 27th, 1838, a date which “the troubles of 1837-38”, they are apt to E. C. Bamett said: “must go down in history in recall the confrontations between the rebels, red letter.” or “patriotes” and government forces at St. Charles and St. Denis on the Richelieu River But first, some background. In 1837, many of east of Montreal, the rout at St. Eustache and the inhabitants of Potton were sons and the Battle of Moore's Corners in Missisquoi daughters of original settlers from the U.S. County. However, here in Brome County who had been loyal to the Crown during the feelings reached a fever pitch too and there American Revolution, and they inherited the was the odd skirmish that might very well political sympathies of their parents. -

HISTORY 1101A (Autumn 2009) the MAKING of CANADA MRT 218, Monday, 5.30-8.30 P.M

1 HISTORY 1101A (Autumn 2009) THE MAKING OF CANADA MRT 218, Monday, 5.30-8.30 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Jeff Keshen Office: Room 110, 155 Seraphin Marion Office Hours - Monday, 3-5 Phone: 562-5800, ext. 1287 (or by appointment) Fax - 562-5995 e-mail- [email protected] Teaching Assistants - TBA ** FOR A COURSE SYLLABUS WITH ALL LECTURE OUTLINES GO TO: http://www.sass.uottawa.ca/els-sae-shared/pdf/syllabus-history_1101-2009_revised.pdf This course will cover some of the major political, economic, social, and cultural themes in order to build a general understanding of Canadian history. As such, besides examining the lives of prime ministers and other elites, we will also analyse, for example, what things were like for ordinary people; besides focussing upon the French-English divide, we will also look at issues revolving around gender roles and Canada’s First Peoples; and besides noting cultural expressions such as "high art," we will also touch upon things such as various forms of popular entertainment. The general story will come from the lectures. However, your outline will refer to chapters from the Francis, Smith and Jones texts, Journeys. You should read these, especially if parts of the lecture remain unclear. The textbook will provide background; it will not replicate the lectures. Required readings will consist of a series of primary source documents. The lectures will refer to many of those documents, suggesting how they might be understood in relation to the general flow of events. Thus, on the mid-term test and final examination, you should be able to utilize the required readings and the lecture material in responding to questions. -

August 1993 OHS Bulletin, Issue 86

s\ ' . ' V (i. R‘ LI‘ —f» Ur:~~ ‘ 0 14:“ O 7-‘ ,_l V/‘I/4.. £11 I’ ' “I .4’ ‘ "V 7‘ 5 5151 Yonge Street, Willowdale, Ontario M2N 5P5 Issue 86 - July — August 1993 Ontario’s first press and newspaper commemorated 1993 marks the bicentennial including the 250 year-old of Ontario’s first newspaper wooden press, which produced and printing press, established the first edition of The Gazette, in 1793 at Newark (now used by the Kings Printer to Niagara-on-the-Lake) by Upper John Graves Simcoe, Louis Canada’s first Lieutenant Roy. The museum is open to Governor, John Graves the public until Labour Day, Simcoe. September 6, and throughout Simcoe set up the govern- October for school and group ment printing office and news- tours. paper, The Upper Canada Several other commemora- Gazette or American Oracle, tive events have marked the shortly after he arrived in the bicentennial. Of particular newly-formed province, to con- importance was the unveiling vey news about government on June 9 of a plaque in policies, statutes and proclama- Simcoe Parks Heritage Garden tions. The Gazette also played a at Niagara-on—the-Lake in hon- significant role as a community our of the first newspaper. The newspaper, containing foreign bronze, lectern-style plaque, and domestic news, editorials erected by the Ontario Commu- and advertising. The paper nity Newspapers Association, operated for over 50 years, is situated with other markers making it, today, an invaluable identifying Niagara’s founding source of historical information history. The unveiling initiated on Ontario’s early develop- three days of meetings and spe- ment. -

The Canadian Quaker History Journal No

The Canadian Quaker History Journal No. 66 2001 Special issue celebrating the 70th Anniversary of Camp NeeKauNis and the Canadian Friends Service Committee The Canadian Quaker History Journal No. 66 2001 Contents Special Issue: 70th Anniversary of Camp NeeKauNis and the Canadian Friends Service Committee Meeting Place of Friends: A brief history of Camp NeeKauNis by Stirling Nelson 1 CFSC Support to Friends Rural Centre, Rasulia, Hoshangabad District, Madhya Pradesh, India by Peter and Rose Mae Harkness 5 The Grindstone Era: Looking Back, Looking Ahead by Murray Thomson 12 The Origins of the Canadian Quaker Committee on Native Concerns by Jo Vellacott 17 Fred Haslam (1897-1979): “Mr Canadian Friend” - A Personal View by Dorothy Muma 23 A Benevolent Alliance: The Canadian Save the Children Fund and the Canadian Friends Service Committee between the Two World Wars by Meghan Cameron 35 Trying to Serve God in the Spirit of Christ: The Canadian Friends Service Committee in the Vietnam War Era by Kathleen Herztberg 61 Rogers Family - Radio and Cable Communications by Sandra McCann Fuller 73 An Account of the Widdifield Family by Emma Knowles MacMillan 79 The Black Creek Meeting House: A description from 1876 by Christopher Densmore 96 Book Review: T.D. Seymour Bassett “The God’s of the Hills” by Robynne Rogers Healey 99 The Canadian Quaker History Journal is published annually by the Canadian Friends Historical Association (as part of the annual membership subscription to the Association). Applications for membership may be made to the address listed below. Membership fees for 2002 are: Libraries and Institutions $15.00 General Membership $10.00 Life Membership $200.00 Contents of the published articles are the responsibility of the authors. -

La Bataille De Saint-Denis

L A S É R I E D E S B A T A I L L E S C A N A D I E N N E S La bataille de Saint-Denis par Elinor Kyte Senior L A S É R I E D E S B A T A I L L E S C A N A D I E N N E S La bataille de Saint-Denis L A S É R I E D E S B A T A I L L E S C A N A D I E N N E S La bataille de Saint-Denis par Elinor Kyte Senior Musée canadien de la guerre La série des batailles canadiennes no 7 BALMUIR Musée canadien de la guerre BOOK PUBLISHING LTD. ©1990 MUSÉE CANADIEN DE LA GUERRE Balmuir Book Publishing Limited C.P. 160, Succursale postale B Toronto (Ontario) M5T 2T3 ISBN 0-919511-45-7 L A S É R I E D E S B A T A I L L E S C A N A D I E N N E S Au fil de son histoire, le Canada a vécu des moments fort difficiles, des luttes d'une envergure variable mais qui eurent toutes un effet marquant sur le développement du pays et qui ont modifié ou reflété le caractère de son peuple. La série présentée par le Musée canadien de la guerre décrit ces batailles et événements au moyen de narrations faites par des historiens dûment qualifiés et rehaussées par des documents visuels complétant très bien le texte.