Copyright by Shweta Prem Agrawal 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Data Encryption Standard (DES) – History

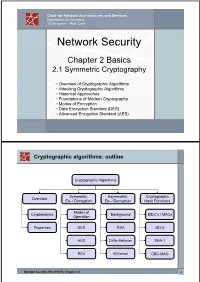

Chair for Network Architectures and Services Department of Informatics TU München – Prof. Carle Network Security Chapter 2 Basics 2.1 Symmetric Cryptography • Overview of Cryptographic Algorithms • Attacking Cryptographic Algorithms • Historical Approaches • Foundations of Modern Cryptography • Modes of Encryption • Data Encryption Standard (DES) • Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) Cryptographic algorithms: outline Cryptographic Algorithms Symmetric Asymmetric Cryptographic Overview En- / Decryption En- / Decryption Hash Functions Modes of Cryptanalysis Background MDC’s / MACs Operation Properties DES RSA MD-5 AES Diffie-Hellman SHA-1 RC4 ElGamal CBC-MAC Network Security, WS 2010/11, Chapter 2.1 2 Basic Terms: Plaintext and Ciphertext Plaintext P The original readable content of a message (or data). P_netsec = „This is network security“ Ciphertext C The encrypted version of the plaintext. C_netsec = „Ff iThtIiDjlyHLPRFxvowf“ encrypt key k1 C P key k2 decrypt In case of symmetric cryptography, k1 = k2. Network Security, WS 2010/11, Chapter 2.1 3 Basic Terms: Block cipher and Stream cipher Block cipher A cipher that encrypts / decrypts inputs of length n to outputs of length n given the corresponding key k. • n is block length Most modern symmetric ciphers are block ciphers, e.g. AES, DES, Twofish, … Stream cipher A symmetric cipher that generats a random bitstream, called key stream, from the symmetric key k. Ciphertext = key stream XOR plaintext Network Security, WS 2010/11, Chapter 2.1 4 Cryptographic algorithms: overview -

Symmetric Encryption: AES

Symmetric Encryption: AES Yan Huang Credits: David Evans (UVA) Advanced Encryption Standard ▪ 1997: NIST initiates program to choose Advanced Encryption Standard to replace DES ▪ Why not just use 3DES? 2 AES Process ▪ Open Design • DES: design criteria for S-boxes kept secret ▪ Many good choices • DES: only one acceptable algorithm ▪ Public cryptanalysis efforts before choice • Heavy involvements of academic community, leading public cryptographers ▪ Conservative (but “quick”): 4 year process 3 AES Requirements ▪ Secure for next 50-100 years ▪ Royalty free ▪ Performance: faster than 3DES ▪ Support 128, 192 and 256 bit keys • Brute force search of 2128 keys at 1 Trillion keys/ second would take 1019 years (109 * age of universe) 4 AES Round 1 ▪ 15 submissions accepted ▪ Weak ciphers quickly eliminated • Magenta broken at conference! ▪ 5 finalists selected: • MARS (IBM) • RC6 (Rivest, et. al.) • Rijndael (Belgian cryptographers) • Serpent (Anderson, Biham, Knudsen) • Twofish (Schneier, et. al.) 5 AES Evaluation Criteria 1. Security Most important, but hardest to measure Resistance to cryptanalysis, randomness of output 2. Cost and Implementation Characteristics Licensing, Computational, Memory Flexibility (different key/block sizes), hardware implementation 6 AES Criteria Tradeoffs ▪ Security v. Performance • How do you measure security? ▪ Simplicity v. Complexity • Need complexity for confusion • Need simplicity to be able to analyze and implement efficiently 7 Breaking a Cipher ▪ Intuitive Impression • Attacker can decrypt secret messages • Reasonable amount of work, actual amount of ciphertext ▪ “Academic” Ideology • Attacker can determine something about the message • Given unlimited number of chosen plaintext-ciphertext pairs • Can perform a very large number of computations, up to, but not including, 2n, where n is the key size in bits (i.e. -

David Wong Snefru

SHA-3 vs the world David Wong Snefru MD4 Snefru MD4 Snefru MD4 MD5 Merkle–Damgård SHA-1 SHA-2 Snefru MD4 MD5 Merkle–Damgård SHA-1 SHA-2 Snefru MD4 MD5 Merkle–Damgård SHA-1 SHA-2 Snefru MD4 MD5 Merkle–Damgård SHA-1 SHA-2 Keccak BLAKE, Grøstl, JH, Skein Outline 1.SHA-3 2.derived functions 3.derived protocols f permutation-based cryptography AES is a permutation input AES output AES is a permutation 0 input 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 key 0 AES 0 0 0 0 0 0 output 0 Sponge Construction f Sponge Construction 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 f 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 Sponge Construction 0 0 0 1 r 0 0 0 1 f 0 1 0 0 c 0 0 0 1 Sponge Construction 0 0 0 1 r 0 0 0 1 f r c 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 c 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 key 0 AES 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Sponge Construction message 0 1 0 1 0 ⊕ 1 0 0 f 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 Sponge Construction message 0 0 0 ⊕ ⊕ 0 f 0 0 0 0 Sponge Construction message 0 0 0 ⊕ ⊕ 0 f f 0 0 0 0 Sponge Construction message 0 0 0 ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ 0 f f 0 0 0 0 Sponge Construction message 0 0 0 ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ 0 f f f 0 0 0 0 Sponge Construction message 0 0 0 ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ 0 f f f 0 0 0 0 absorbing Sponge Construction message output 0 0 0 ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ 0 f f f 0 0 0 0 absorbing Sponge Construction message output 0 0 0 ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ 0 f f f f 0 0 0 0 absorbing Sponge Construction message output 0 0 0 ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ 0 f f f f 0 0 0 0 absorbing Sponge Construction message output 0 0 0 ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ 0 f f f f f 0 0 0 0 absorbing Sponge Construction message output 0 0 0 ⊕ ⊕ ⊕ 0 f f f f f 0 0 0 0 absorbing squeezing Keccak Guido Bertoni, Joan Daemen, Michaël Peeters and Gilles Van Assche 2007 SHA-3 competition 2012 2007 SHA-3 competition 2012 SHA-3 standard -

NISTIR 7620 Status Report on the First Round of the SHA-3

NISTIR 7620 Status Report on the First Round of the SHA-3 Cryptographic Hash Algorithm Competition Andrew Regenscheid Ray Perlner Shu-jen Chang John Kelsey Mridul Nandi Souradyuti Paul NISTIR 7620 Status Report on the First Round of the SHA-3 Cryptographic Hash Algorithm Competition Andrew Regenscheid Ray Perlner Shu-jen Chang John Kelsey Mridul Nandi Souradyuti Paul Information Technology Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899-8930 September 2009 U.S. Department of Commerce Gary Locke, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology Patrick D. Gallagher, Deputy Director NISTIR 7620: Status Report on the First Round of the SHA-3 Cryptographic Hash Algorithm Competition Abstract The National Institute of Standards and Technology is in the process of selecting a new cryptographic hash algorithm through a public competition. The new hash algorithm will be referred to as “SHA-3” and will complement the SHA-2 hash algorithms currently specified in FIPS 180-3, Secure Hash Standard. In October, 2008, 64 candidate algorithms were submitted to NIST for consideration. Among these, 51 met the minimum acceptance criteria and were accepted as First-Round Candidates on Dec. 10, 2008, marking the beginning of the First Round of the SHA-3 cryptographic hash algorithm competition. This report describes the evaluation criteria and selection process, based on public feedback and internal review of the first-round candidates, and summarizes the 14 candidate algorithms announced on July 24, 2009 for moving forward to the second round of the competition. The 14 Second-Round Candidates are BLAKE, BLUE MIDNIGHT WISH, CubeHash, ECHO, Fugue, Grøstl, Hamsi, JH, Keccak, Luffa, Shabal, SHAvite-3, SIMD, and Skein. -

Data Intensive Dynamic Scheduling Model and Algorithm for Cloud Computing Security Md

1796 JOURNAL OF COMPUTERS, VOL. 9, NO. 8, AUGUST 2014 Data Intensive Dynamic Scheduling Model and Algorithm for Cloud Computing Security Md. Rafiqul Islam1,2 1Computer Science Department, American International University Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh 2Computer Science and Engineering Discipline, Khulna University, Khulna, Bangladesh Email: [email protected] Mansura Habiba Computer Science Department, American International University Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh Email: [email protected] Abstract—As cloud is growing immensely, different point cloud computing has gained widespread acceptance. types of data are getting more and more dynamic in However, without appropriate security and privacy terms of security. Ensuring high level of security for solutions designed for clouds, cloud computing becomes all data in storages is highly expensive and time a huge failure [2, 3]. Amazon provides a centralized consuming. Unsecured services on data are also cloud computing consisting simple storage services (S3) becoming vulnerable for malicious threats and data and elastic compute cloud (EC2). Google App Engine is leakage. The main reason for this is that, the also an example of cloud computing. While these traditional scheduling algorithms for executing internet-based online services do provide huge amounts different services on data stored in cloud usually of storage space and customizable computing resources. sacrifice security privilege in order to achieve It is eliminating the responsibility of local machines for deadline. To provide adequate security without storing and maintenance of data. Considering various sacrificing cost and deadline for real time data- kinds of data for each user stored in the cloud and the intensive cloud system, security aware scheduling demand of long term continuous assurance of their data algorithm has become an effective and important safety, security is one of the prime concerns for the feature. -

Performance Analysis of Cryptographic Hash Functions Suitable for Use in Blockchain

I. J. Computer Network and Information Security, 2021, 2, 1-15 Published Online April 2021 in MECS (http://www.mecs-press.org/) DOI: 10.5815/ijcnis.2021.02.01 Performance Analysis of Cryptographic Hash Functions Suitable for Use in Blockchain Alexandr Kuznetsov1 , Inna Oleshko2, Vladyslav Tymchenko3, Konstantin Lisitsky4, Mariia Rodinko5 and Andrii Kolhatin6 1,3,4,5,6 V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University, Svobody sq., 4, Kharkiv, 61022, Ukraine E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 2 Kharkiv National University of Radio Electronics, Nauky Ave. 14, Kharkiv, 61166, Ukraine E-mail: [email protected] Received: 30 June 2020; Accepted: 21 October 2020; Published: 08 April 2021 Abstract: A blockchain, or in other words a chain of transaction blocks, is a distributed database that maintains an ordered chain of blocks that reliably connect the information contained in them. Copies of chain blocks are usually stored on multiple computers and synchronized in accordance with the rules of building a chain of blocks, which provides secure and change-resistant storage of information. To build linked lists of blocks hashing is used. Hashing is a special cryptographic primitive that provides one-way, resistance to collisions and search for prototypes computation of hash value (hash or message digest). In this paper a comparative analysis of the performance of hashing algorithms that can be used in modern decentralized blockchain networks are conducted. Specifically, the hash performance on different desktop systems, the number of cycles per byte (Cycles/byte), the amount of hashed message per second (MB/s) and the hash rate (KHash/s) are investigated. -

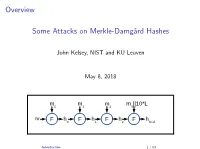

Some Attacks on Merkle-Damgård Hashes

Overview Some Attacks on Merkle-Damg˚ardHashes John Kelsey, NIST and KU Leuven May 8, 2018 m m m m ||10*L 0 1 2 3 iv F h F h F h F h 0 1 2 final Introduction 1 / 63 Overview I Cryptographic Hash Functions I Thinking About Collisions I Merkle-Damg˚ardhashing I Joux Multicollisions[2004] I Long-Message Second Preimage Attacks[1999,2004] I Herding and the Nostradamus Attack[2005] Introduction 2 / 63 Why Talk About These Results? I These are very visual results{looking at the diagram often explains the idea. I The results are pretty accessible. I Help you think about what's going on inside hashing constructions. Introduction 3 / 63 Part I: Preliminaries/Review I Hash function basics I Thinking about collisions I Merkle-Damg˚ardhash functions Introduction 4 / 63 Cryptographic Hash Functions I Today, they're the workhorse of crypto. I Originally: Needed for digital signatures I You can't sign 100 MB message{need to sign something short. I \Message fingerprint" or \message digest" I Need a way to condense long message to short string. I We need a stand-in for the original message. I Take a long, variable-length message... I ...and map it to a short string (say, 128, 256, or 512 bits). Cryptographic Hash Functions 5 / 63 Properties What do we need from a hash function? I Collision resistance I Preimage resistance I Second preimage resistance I Many other properties may be important for other applications Note: cryptographic hash functions are designed to behave randomly. Cryptographic Hash Functions 6 / 63 Collision Resistance The core property we need. -

Kapitel 6 Der Advanced Encryption Standard Rijndael

Kap. 6: Der Advanced Encryption Standard Rijndael Dieses ging von Anfang an davon aus, daß der zu wahlende¨ Algorith- mus stark¨ er sein musse¨ als Triple DES; er sollte zwanzig bis dreißig Jahre lang anwendbar sein und dementsprechende Sicherheit bieten. Nach einer internationalen Konferenz uber¨ die Auswahlkriterien am 15. April 1997 verof¨ fentlichte es am 12. September 1997 die endgultige¨ Ausschreibung. Kapitel 6 Minimalanforderung an die einzureichenden Algorithmen waren da- nach, daß es sich um symmetrische Blockchiffren handeln muß, die min- Der Advanced Encryption Standard Rijndael destens eine Blocklange¨ von 128 Bit bei Schlussell¨ angen¨ von 128 Bit, 192 Bit und 256 Bit vorsieht. §1: Geschichte und Auswahlkriterien Als Kriterien fur¨ die Wahl zwischen den einzelnen Algorithmen wurden DES wurde in Zusammenarbeit mit der National Security Agency der die folgenden Aspekte genannt: Vereinigten Staaten von IBM entwickelt und dann als amerikanischer 1. Sicherheit: Wie sicher ist der Algorithmus im Vergleich zu den Standard verkundet.¨ Diese Vorgehensweise weckte von Anfang an den anderen Kandidaten? Inwieweit ist seine Ausgabe ununterscheidbar Verdacht, daß moglicherweise¨ eine Falltur¨ “ eingebaut sei, insbeson- von der einer Zufallspermutation? Wie gut ist die mathematische ” dere da zumindest ursprunglich¨ nicht alle Design-Kriterien publiziert Basis fur¨ die Sicherheit des Algorithmus begrundet?¨ (Im Gegensatz wurden. zu DES sollten dieses Mal alle Kriterien publiziert werden.) 2. Kosten: Welche Lizensgebuhren¨ werden fallig?¨ -

Block Cipher Based Hashed Functions

ANALYSIS OF THREE BLOCK CIPHER BASED HASH FUNCTIONS: WHIRLPOOL, GRØSTL AND GRINDAHL A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF APPLIED MATHEMATICS OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY RITA ISMAILOVA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHYLOSOPHY IN CRYPTOGRAPHY SEPTEMBER 2012 Approval of the thesis: ANALYSIS OF THREE BLOCK CIPHER BASED HASH FUNCTIONS: WHIRLPOOL, GRØSTL AND GRINDAHL submitted by RITA ISMAILOVA in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Department of Cryptography, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Bülent Karasözen ____________ Director, Graduate School of Applied Mathematics Prof. Dr. Ferruh Özbudak ____________ Head of Department, Cryptography Assoc. Prof. Dr. Melek Diker Yücel ____________ Supervisor, Department of Electrical and Electronics Engineering Examining Committee Members: Prof. Dr. Ersan Akyıldız ____________ Department of Mathematics, METU Assoc. Prof. Dr. Melek Diker Yücel ____________ Department of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, METU Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ali Doğanaksoy ____________ Department of Mathematics, METU Assist. Prof. Dr. Zülfükar Saygı ____________ Department of Mathematics, TOBB ETU Dr. Hamdi Murat Yıldırım ____________ Department of Computer Technology and Information Systems, Bilkent University Date: ____________ I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last Name: RITA ISMAILOVA Signature : iii ABSTRACT ANALYSIS OF THREE BLOCK CIPHER BASED HASH FUNCTIONS: WHIRLPOOL, GRØSTL AND GRINDAHL Ismailova, Rita Ph.D., Department of Cryptography Supervisor : Assoc. -

On Probabilities of Hash Value Matches

Printer - please drop in Elsevier (tree) logo Computers 8 Security Vol. 17, No.2, pp. 171- 174, 1998 0 1998 Elsevier Science Limited All rights reserved. Printed in Great Britain 0167-4048/98 $19.00 On Probabilities of Hash Value Matches Mohammad Peyraviana, Allen Roginskya, Ajay Kshemkalyanib alBM Corporation, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709, USA bECECS Detlartment. University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45221, USAL ’ ‘ _ Hash functions are used in authentication and cryptography, as hash function is said to be collision resistant if it is hard well as for the efficient storage and retrieval of data using hashed to find two input strings that map to the same hash keys. Hash functions are susceptible to undesirable collisions. To design or choose an appropriate hash function for an application, value.The problem of constructing fast hash functions it is essential to estimate the probabilities with which these colli- that also have low collision rates is studied in [S]. Key- sions can occur. In this paper we consider two problems: one of to-address transformation techniques for file access evaluating the probability of no collision at all and one of finding and their performance have been studied in [8]. Given a bound for the probability of a collision with a particular hash k, the number of hashed values that have been used in value. The quality of these estimates under various values of the parameters is also discussed. a hashing scheme in which input strings are mapped to random values, the expected number of locations Keywords: hash functions, security, cryptography, indexing, databases that must be looked at until an empty hashed value is found is formulated in [lo]. -

Differential Cryptanalysis of the Data Encryption Standard

Differential Cryptanalysis of the Data Encryption Standard Eli Biham1 Adi Shamir2 December 7, 2009 1Computer Science Department, Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa 32000, Israel. Email: [email protected], WWW: http://www.cs.technion.ac.il/˜biham/. 2Department of Applied Mathematics and Computer Science, The Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel. Email: [email protected]. This versionofthebookisprocessedfromtheauthor’soriginalLaTeXfiles,andmaybe differentlypaginatedthantheprintedbookbySpringer(1993). Copyright:EliBihamandAdiShamir. Preface The security of iterated cryptosystems and hash functions has been an active research area for many years. The best known and most widely used function of this type is the Data Encryption Standard (DES). It was developed at IBM and adopted by the National Bureau of Standards in the mid 70’s, and has successfully withstood all the attacks published so far in the open literature. Since the introduction of DES, many other iterated cryptosystems were developed, but their design and analysis were based on ad-hoc heuristic arguments, with no theoretical justification. In this book, we develop a new type of cryptanalytic attack which can be successfully applied to many iterated cryptosystems and hash functions. It is primarily a chosen plaintext attack but under certain circumstances, it can also be applied as a known plaintext attack. We call it “differen- tial cryptanalysis”, since it analyzes the evolution of differences when two related plaintexts are encrypted under the same key. Differential cryptanalysis is the first published attack which is capable of breaking the full 16-round DES in less than 255 complexity. The data analysis phase computes the key by analyzing about 236 ciphertexts in 237 time. -

Basic Cryptanalysis Methods on Block Ciphers

1 BASIC CRYPTANALYSIS METHODS ON BLOCK CIPHERS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF APPLIED MATHEMATICS OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY DILEK˙ C¸ELIK˙ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN CRYPTOGRAPHY MAY 2010 Approval of the thesis: BASIC CRYPTANALYSIS METHODS ON BLOCK CIPHERS submitted by DILEK˙ C¸ELIK˙ in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Department of Cryptography, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Ersan AKYILDIZ Director, Graduate School of Applied Mathematics Prof. Dr. Ferruh OZBUDAK¨ Head of Department, Cryptography Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ali DOGANAKSOY˘ Supervisor, Department of Mathematics, METU Examining Committee Members: Prof. Dr. Ferruh OZBUDAK¨ Department of Mathematics, METU Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ali DOGANAKSOY˘ Department of Mathematics, METU Assist. Prof. Dr. Zulf¨ ukar¨ SAYGI Department of Mathematics, TOBB ETU Dr. Muhiddin UGUZ˘ Department of Mathematics, METU Dr. Murat CENK Department of Cryptography, METU Date: I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last Name: DILEK˙ C¸ELIK˙ Signature : iii ABSTRACT BASIC CRYPTANALYSIS METHODS ON BLOCK CIPHERS C¸elik, Dilek M.S., Department of Cryptography Supervisor : Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ali DOGANAKSOY˘ May 2010, 119 pages Differential cryptanalysis and linear cryptanalysis are the first significant methods used to at- tack on block ciphers. These concepts compose the keystones for most of the attacks in recent years.