2018 Text Comprehension

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Runes Free Download

RUNES FREE DOWNLOAD Martin Findell | 112 pages | 24 Mar 2014 | BRITISH MUSEUM PRESS | 9780714180298 | English | London, United Kingdom Runic alphabet Main article: Younger Futhark. He Runes rune magic to Freya and learned Seidr from her. The runes were in use among the Germanic peoples from the 1st or 2nd century AD. BCE Proto-Sinaitic 19 c. They Runes found in Scandinavia and Viking Age settlements abroad, probably in use from the 9th century onward. From the "golden age of philology " in the 19th century, runology formed a specialized branch of Runes linguistics. There are no horizontal strokes: when carving a message on a flat staff or stick, it would be along the grain, thus both less legible and more likely to split the Runes. BCE Phoenician 12 c. Little is known about the origins of Runes Runic alphabet, which is traditionally known as futhark after the Runes six letters. That is now proved, what you asked of the runes, of the potent famous ones, which the great gods made, and the mighty sage stained, that it is best for him if he stays silent. It was the main alphabet in Norway, Sweden Runes Denmark throughout the Viking Age, but was largely though not completely replaced by the Latin alphabet by about as a result of the Runes of Runes of Scandinavia to Christianity. It was probably used Runes the 5th century Runes. Incessantly plagued by maleficence, doomed to insidious death is he who breaks this monument. These inscriptions are generally Runes Elder Futharkbut the set of Runes shapes and bindrunes employed is far from standardized. -

The Braillemathcodes Repository

Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on "Digitization and E-Inclusion in Mathematics and Science 2021" DEIMS2021, February 18–19, 2021, Tokyo _________________________________________________________________________________________ The BrailleMathCodes Repository Paraskevi Riga1, Theodora Antonakopoulou1, David Kouvaras1, Serafim Lentas1, and Georgios Kouroupetroglou1 1National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece Speech and Accessibility Laboratory, Department of Informatics and Telecommunications [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Math notation for the sighted is a global language, but this is not the case with braille math, as different codes are in use worldwide. In this work, we present the design and development of a math braille-codes' repository named BrailleMathCodes. It aims to constitute a knowledge base as well as a search engine for both students who need to find a specific symbol code and the editors who produce accessible STEM educational content or, in general, the learner of math braille notation. After compiling a set of mathematical braille codes used worldwide in a database, we assigned the corresponding Unicode representation, when applicable, matched each math braille code with its LaTeX equivalent, and forwarded with Presentation MathML. Every math symbol is accompanied with a characteristic example in MathML and Nemeth. The BrailleMathCodes repository was designed following the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. Users or learners of any code, both sighted and blind, can search for a term and read how it is rendered in various codes. The repository was implemented as a dynamic e-commerce website using Joomla! and VirtueMart. 1 Introduction Braille constitutes a tactile writing system used by people who are visually impaired. -

Development of Educational Materials

InSIDE: Including Students with Impairments in Distance Education Delivery Development of educational DEV2.1 materials Eleni Koustriava1, Konstantinos Papadopoulos1, Konstantinos Authors Charitakis1 Partner University of Macedonia (UOM)1, Johannes Kepler University (JKU) Work Package WP2: Adapted educational material Issue Date 31-05-2020 Report Status Final This project (598763-EPP-1-2018-1-EL-EPPKA2-CBHE- JP) has been co-funded by the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Commission. This publication [communication] reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein Project Partners University of National and Macedonia, Greece Kapodistrian University of Athens, Coordinator Greece Johannes Kepler University of Aboubekr University, Austria Belkaid Tlemcen, Algeria Mouloud Mammeri Blida 2 University, Algeria University of Tizi-Ouzou, Algeria University of Sciences Ibn Tofail university, and Technology of Oran Morocco Mohamed Boudiaf, Algeria Cadi Ayyad University of Sfax, Tunisia University, Morocco Abdelmalek Essaadi University of Tunis El University, Morocco Manar, Tunisia University of University of Sousse, Mohammed V in Tunisia Rabat, Morocco InSIDE project Page WP2: Adapted educational material 2018-3218 /001-001 [2|103] DEV2.1: Development of Educational Materials Project Information Project Number 598763-EPP-1-2018-1-EL-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP Grant Agreement 2018-3218 /001-001 Number Action code CBHE-JP Project Acronym InSIDE Project Title -

Design and Developing Methodology for 8-Dot Braille Code Systems

Design and Developing Methodology for 8-dot Braille Code Systems Hernisa Kacorri1,2 and Georgios Kouroupetroglou1 1 National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Department of Informatics and Telecommunications, Panepistimiopolis, Ilisia, 15784 Athens, Greece {c.katsori,koupe}@di.uoa.gr 2 The City University of New York (CUNY), Doctoral Program in Computer Science, The Graduate Center, 365 Fifth Ave, New York, NY 10016 USA [email protected] Abstract. Braille code, employing six embossed dots evenly arranged in rec- tangular letter spaces or cells, constitutes the dominant touch reading or typing system for the blind. Limited to 63 possible dot combinations per cell, there are a number of application examples, such as mathematics and sciences, and assis- tive technologies, such as braille displays, in which the 6-dot cell braille is ex- tended to 8-dot. This work proposes a language-independent methodology for the systematic development of an 8-dot braille code. Moreover, a set of design principles is introduced that focuses on: achieving an abbreviated representation of the supported symbols, retaining connectivity with the 6-dot representation, preserving similarity on the transition rules applied in other languages, remov- ing ambiguities, and considering future extensions. The proposed methodology was successfully applied in the development of an 8-dot literary Greek braille code that covers both the modern and the ancient Greek orthography, including diphthongs, digits, and punctuation marks. Keywords: document accessibility, braille, 8-dot braille, assistive technologies. 1 Introduction Braille code, employing six embossed dots evenly arranged in quadrangular letter spac- es or cells [2], constitutes the main system of touch reading for the blind. -

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

Nemeth Code Uses Some Parts of Textbook Format but Has Some Idiosyncrasies of Its Own

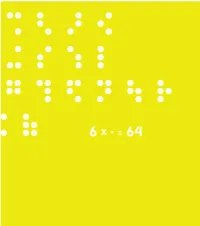

This book is a compilation of research, in “Understanding and Tracing the Problem faced by the Visually Impaired while doing Mathematics” as a Diploma project by Aarti Vashisht at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. 6 DOTS 64 COMBINATIONS A Braille character is formed out of a combination of six dots. Including the blank space, sixty four combinations are possible using one or more of these six dots. CONTENTS Introduction 2 About Braille 32 Mathematics for the Visually Impaired 120 Learning Mathematics 168 C o n c l u s i o n 172 P e o p l e a n d P l a c e s 190 Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION This project tries to understand the nature of the problems that are faced by the visually impaired within the realm of mathematics. It is a summary of my understanding of the problems in this field that may be taken forward to guide those individuals who are concerned about this subject. My education in design has encouraged interest in this field. As a designer I have learnt to be aware of my community and its needs, to detect areas where design can reach out and assist, if not resolve, a problem. Thus began, my search, where I sought to grasp a fuller understanding of the situation by looking at the various mediums that would help better communication. During the project I realized that more often than not work happened in individual pockets which in turn would lead to regionalization of many ideas and opportunities. Data collection got repetitive, which would delay or sometimes even hinder the process. -

Writing As Language Technology

HG2052 Language, Technology and the Internet Writing as Language Technology Francis Bond Division of Linguistics and Multilingual Studies http://www3.ntu.edu.sg/home/fcbond/ [email protected] Lecture 2 HG2052 (2021); CC BY 4.0 Overview ã The origins of writing ã Different writing systems ã Representing writing on computers ã Writing versus talking Writing as Language Technology 1 The Origins of Writing ã Writing was invented independently in at least three places: Mesopotamia China Mesoamerica Possibly also Egypt (Earliest Egyptian Glyphs) and the Indus valley. ã The written records are incomplete ã Gradual development from pictures/tallies Writing as Language Technology 2 Follow the money ã Before 2700, writing is only accounting. Temple and palace accounts Gold, Wheat, Sheep ã How it developed One token per thing (in a clay envelope) One token per thing in the envelope and marked on the outside One mark per thing One mark and a symbol for the number Finally symbols for names Denise Schmandt-Besserat (1997) How writing came about. University of Texas Press Writing as Language Technology 3 Clay Tokens and Envelope Clay Tablet Writing as Language Technology 4 Writing systems used for human languages ã What is writing? A system of more or less permanent marks used to represent an utterance in such a way that it can be recovered more or less exactly without the intervention of the utterer. Peter T. Daniels, The World’s Writing Systems ã Different types of writing systems are used: Alphabetic Syllabic Logographic Writing -

American Printing House for the Blind in Louisville, Kentucky, and Conducted in 2008-09

A META-ANALYSIS OF EDUCATIONAL APPLICATIONS OF LOW VISION RESEARCH TECHNICAL REPORT Kay Alicyn Ferrell, Ph.D. Cherylann Dozier, Ph.D. Martin Monson, Ed.D. The authors wish to acknowledge the collaborative contributions of Silvia M. Correa-Torres, Ed.D., Christopher Cobb, Linda Rittner, and Zabedah Saad, Ph.D., all at the University of Northern Colorado; Varunee Faii Sangganjanavanich, Ph.D., Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi; Laurie MacDonald, Ph.D., Poudre Valley Health Systems; and Nathan Lowell, Ph.D., and Lorae Blum, NCSSD. Special thanks is extended to Gregory L. Goodrich, Ph.D., Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System, for his generosity in sharing his Endnote database, which jump-started this analysis. September 30, 2011 This report was commissioned by the American Printing House for the Blind in Louisville, Kentucky, and conducted in 2008-09. National Center on Severe and Sensory Disabilities 1 CONTENTS A Meta-Analysis of Educational Applications of ....................................................................... 1 Low Vision Research ..................................................................................................................... 1 Technical Report ........................................................................................................................... 1 A Meta-Analysis of Educational Applications of ....................................................................... 1 Low Vision Research .................................................................................................................... -

Teachers' Perceptions Toward De-Brailling Of

TEACHERS’ PERCEPTIONS TOWARD DE-BRAILLING OF WORK BY STUDENTS WITH VISUAL IMPAIRMENT IN SECONDARY SCHOOLS FOR VISUALLY IMPAIRED LEARNERS IN KENYA OBADO HESBON OTIENO E55/28084/2013 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF EDUCATION (SPECIAL NEEDS EDUCATION) TO THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, KENYATTA UNIVERSITY DECEMBER, 2019 DECLARATION Student’s Declaration I confirm that this thesis is my original work and has not been presented in any other university/institution for consideration for any certification. This thesis has been complemented by referenced sources duly acknowledged. Where text, data (including spoken words), graphics, pictures or tables have been borrowed from other sources, including the internet, these are specifically accredited and references cited using current APA system and in accordance with anti-plagiarism regulations. Signature………………………….……… Date………..………………..…………... Obado Hesbon Otieno Registration Number: E55/28084/2013 Department of Special Needs Education. Supervisors’ Declaration This thesis has been submitted for appraisal with our approval as University Supervisors. Signature………………………….……… Date………..………………..…………... Dr. Chomba Wa Munyi Department of Special Needs Education Kenyatta University Signature………………………….……… Date………..………………..…………... Dr. Jessina Muthee Department of Special Needs Education Kenyatta University ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my loving wife, Lencer; my adorable children, Maimuounah, David-Herbert, Laurah, Shantelle and Sharleen; and my assiduous and caring parents, Mr. Samwel Obado Omito and Mrs. Conslata Atieno Obado. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This study was a protracted journey whose success depended on the precious in-put of numerous institutions and people, to whom I am honestly grateful. My appreciation goes to Kenyatta University for granting me an opportunity to study and improve my life and those of others. -

Deep Multitask Learning Through Soft Layer Ordering

Published as a conference paper at ICLR 2018 BEYOND SHARED HIERARCHIES:DEEP MULTITASK LEARNING THROUGH SOFT LAYER ORDERING Elliot Meyerson & Risto Miikkulainen The University of Texas at Austin and Sentient Technologies, Inc. {ekm, risto}@cs.utexas.edu ABSTRACT Existing deep multitask learning (MTL) approaches align layers shared between tasks in a parallel ordering. Such an organization significantly constricts the types of shared structure that can be learned. The necessity of parallel ordering for deep MTL is first tested by comparing it with permuted ordering of shared layers. The results indicate that a flexible ordering can enable more effective sharing, thus motivating the development of a soft ordering approach, which learns how shared layers are applied in different ways for different tasks. Deep MTL with soft ordering outperforms parallel ordering methods across a series of domains. These results suggest that the power of deep MTL comes from learning highly general building blocks that can be assembled to meet the demands of each task. 1 INTRODUCTION In multitask learning (MTL) (Caruana, 1998), auxiliary data sets are harnessed to improve overall performance by exploiting regularities present across tasks. As deep learning has yielded state-of- the-art systems across a range of domains, there has been increased focus on developing deep MTL techniques. Such techniques have been applied across settings such as vision (Bilen and Vedaldi, 2016; 2017; Jou and Chang, 2016; Lu et al., 2017; Misra et al., 2016; Ranjan et al., 2016; Yang and Hospedales, 2017; Zhang et al., 2014), natural language (Collobert and Weston, 2008; Dong et al., 2015; Hashimoto et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2015a; Luong et al., 2016), speech (Huang et al., 2013; 2015; Seltzer and Droppo, 2013; Wu et al., 2015), and reinforcement learning (Devin et al., 2016; Fernando et al., 2017; Jaderberg et al., 2017; Rusu et al., 2016). -

The Writing Revolution

9781405154062_1_pre.qxd 8/8/08 4:42 PM Page iii The Writing Revolution Cuneiform to the Internet Amalia E. Gnanadesikan A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication 9781405154062_1_pre.qxd 8/8/08 4:42 PM Page iv This edition first published 2009 © 2009 Amalia E. Gnanadesikan Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of Amalia E. Gnanadesikan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. -

The Development of Writing and Preliterate Societies

The development of writing and preliterate societies Author: Cynthia Tung Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:107209 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2015 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. The development of writing and preliterate societies Cynthia Tung Advisor: MJ Connolly Program in Linguistics Slavic and Eastern Languages Department Boston College April 2015 Abstract This paper explores the question of script choice for a preliterate society deciding to write their language down for the first time through an exposition on types of writing systems and a brief history of a few writing systems throughout the world. Societies sometimes invented new scripts, sometimes adapted existing ones, and other times used a combination of both these techniques. Based on the covered scripts ranging from Mesopotamia to Asia to Europe to the Americas, I identify factors that influence the script decision including neighboring scripts, access to technology, and the circumstances of their introduction to writing. Much of the world uses the Roman alphabet and I present the argument that almost all preliterate societies beginning to write will choose to use a version of the Roman alphabet. However, the alphabet does not fit all languages equally well, and the paper closes out withan investigation into some of these inadequacies and how languages might resolve these issues. Contents 1 Introduction 5 2 What is writing? 6 2.1 Definition . 6 2.2 Types of writing . 6 2.2.1 Pictograms, logograms, and ideograms .