The Braillemathcodes Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Runes Free Download

RUNES FREE DOWNLOAD Martin Findell | 112 pages | 24 Mar 2014 | BRITISH MUSEUM PRESS | 9780714180298 | English | London, United Kingdom Runic alphabet Main article: Younger Futhark. He Runes rune magic to Freya and learned Seidr from her. The runes were in use among the Germanic peoples from the 1st or 2nd century AD. BCE Proto-Sinaitic 19 c. They Runes found in Scandinavia and Viking Age settlements abroad, probably in use from the 9th century onward. From the "golden age of philology " in the 19th century, runology formed a specialized branch of Runes linguistics. There are no horizontal strokes: when carving a message on a flat staff or stick, it would be along the grain, thus both less legible and more likely to split the Runes. BCE Phoenician 12 c. Little is known about the origins of Runes Runic alphabet, which is traditionally known as futhark after the Runes six letters. That is now proved, what you asked of the runes, of the potent famous ones, which the great gods made, and the mighty sage stained, that it is best for him if he stays silent. It was the main alphabet in Norway, Sweden Runes Denmark throughout the Viking Age, but was largely though not completely replaced by the Latin alphabet by about as a result of the Runes of Runes of Scandinavia to Christianity. It was probably used Runes the 5th century Runes. Incessantly plagued by maleficence, doomed to insidious death is he who breaks this monument. These inscriptions are generally Runes Elder Futharkbut the set of Runes shapes and bindrunes employed is far from standardized. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 456 844 IR 058 192 TITLE Sources of Custom-Produced Books: Braille, Audio Recordings, and Large Print. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. REPORT NO DI015 ISSN ISSN-1535-1505 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 107p. AVAILABLE FROM Reference Section, National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, Washington, DC 20542. Web site: http://www.loc.gov/nls/reference/directories.html. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Audiotape Recordings; *Books; Braille; Individual Needs; *Information Sources; Large Type Materials; Reading Materials; Talking Books; Visual Impairments; Volunteers IDENTIFIERS National Library Service for the Blind; *Transcription ABSTRACT This directory lists the names of volunteer groups, individual transcribers, and nonprofit and commercial organizations that transcribe and record books and other reading materials for persons who are blind and physically handicapped. It was compiled from information supplied by organizations and groups who perform these services. The listing is alphabetical by state. Each entry is assigned an index number and specifies such services as Braille transcription, computer-assisted transcription, print enlargements, tape recording, duplication, and binding. Entries also give such Braille code specialties as music, mathematics, and specific languages. The directory contains information in separate sections on state special education contacts and proofreaders certified by the Library of Congress. Wherever Braille groups are listed, it is understood that there is at least one transcriber or proofreader certified by the Library of Congress working with the group/organization. The introduction includes a list of other related documents on the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped (NLS) Web site or available upon request, as well as additional resources for materials available in different formats. -

Dictionary of Braille Music Signs by Bettye Krolick

JBN 0-8444-0 9 C D E F G Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Federation of the Blind (NFB) http://archive.org/details/dictionaryofbraiOObett LIBRARY IOWA DEPARTMENT FOR THE BLIND 524 Fourth Street Des Moines, Iowa 50309-2364 Dictionary of Braille Music Signs by Bettye Krolick National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20542 1979 MT. PLEASANT HIGH SCHOOL LIBRARY Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Krolick, Bettye. Dictionary of braille music signs. At head of title: National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress. Bibliography: p. 182-188 Includes index. 1. Braille music-notation. I. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. II. Title. MT38.K76 78L.24 78-21301 ISBN 0-8444-0277-X . TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD vii PREFACE ix HISTORY OF THE BRAILLE MUSIC CODE ... xi HOW TO LOCATE A DEFINITION xviii DICTIONARY OF SIGNS (A sign that contains two or more cells is listed under its first character.) . 1 •* 1 •• 16 • • •• 3 •• 17 •> 6 •• 17 •• •• 7 •• 17 •• 7 •• 17 •• •• 7 •• 17 •• •• 8 •• 18 •• •• 8 •• 18 •• •• 9 •• 19 •• •• 9 •• 19 • • •• 10 •• 20 • • •• 12 •• 20 •• 14 •• 20 •• •• 14 •• 22 • • •• •• 15 • • 27 •• •• •« •• 15 • • 29 •• • • •« 16 30 •• •• 16 • • 30 30 i: 46 ?: 31 11 47 r. 31 ;: 48 •: 31 i? 58 ?: 31 i; 78 ::' 34 :: 79 a 34 ;: si 35 ;? 86 37 ;: 90 39 ':• 96 40 ;: 102 43 i: 105 45 ;: 113 46 FORMATS FOR BRAILLE MUSIC 122 Format Identification Chart 125 Music in Parallels -

Development of Educational Materials

InSIDE: Including Students with Impairments in Distance Education Delivery Development of educational DEV2.1 materials Eleni Koustriava1, Konstantinos Papadopoulos1, Konstantinos Authors Charitakis1 Partner University of Macedonia (UOM)1, Johannes Kepler University (JKU) Work Package WP2: Adapted educational material Issue Date 31-05-2020 Report Status Final This project (598763-EPP-1-2018-1-EL-EPPKA2-CBHE- JP) has been co-funded by the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Commission. This publication [communication] reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein Project Partners University of National and Macedonia, Greece Kapodistrian University of Athens, Coordinator Greece Johannes Kepler University of Aboubekr University, Austria Belkaid Tlemcen, Algeria Mouloud Mammeri Blida 2 University, Algeria University of Tizi-Ouzou, Algeria University of Sciences Ibn Tofail university, and Technology of Oran Morocco Mohamed Boudiaf, Algeria Cadi Ayyad University of Sfax, Tunisia University, Morocco Abdelmalek Essaadi University of Tunis El University, Morocco Manar, Tunisia University of University of Sousse, Mohammed V in Tunisia Rabat, Morocco InSIDE project Page WP2: Adapted educational material 2018-3218 /001-001 [2|103] DEV2.1: Development of Educational Materials Project Information Project Number 598763-EPP-1-2018-1-EL-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP Grant Agreement 2018-3218 /001-001 Number Action code CBHE-JP Project Acronym InSIDE Project Title -

Design and Developing Methodology for 8-Dot Braille Code Systems

Design and Developing Methodology for 8-dot Braille Code Systems Hernisa Kacorri1,2 and Georgios Kouroupetroglou1 1 National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Department of Informatics and Telecommunications, Panepistimiopolis, Ilisia, 15784 Athens, Greece {c.katsori,koupe}@di.uoa.gr 2 The City University of New York (CUNY), Doctoral Program in Computer Science, The Graduate Center, 365 Fifth Ave, New York, NY 10016 USA [email protected] Abstract. Braille code, employing six embossed dots evenly arranged in rec- tangular letter spaces or cells, constitutes the dominant touch reading or typing system for the blind. Limited to 63 possible dot combinations per cell, there are a number of application examples, such as mathematics and sciences, and assis- tive technologies, such as braille displays, in which the 6-dot cell braille is ex- tended to 8-dot. This work proposes a language-independent methodology for the systematic development of an 8-dot braille code. Moreover, a set of design principles is introduced that focuses on: achieving an abbreviated representation of the supported symbols, retaining connectivity with the 6-dot representation, preserving similarity on the transition rules applied in other languages, remov- ing ambiguities, and considering future extensions. The proposed methodology was successfully applied in the development of an 8-dot literary Greek braille code that covers both the modern and the ancient Greek orthography, including diphthongs, digits, and punctuation marks. Keywords: document accessibility, braille, 8-dot braille, assistive technologies. 1 Introduction Braille code, employing six embossed dots evenly arranged in quadrangular letter spac- es or cells [2], constitutes the main system of touch reading for the blind. -

Expanding Information Access Through Data-Driven Design

©Copyright 2018 Danielle Bragg Expanding Information Access through Data-Driven Design Danielle Bragg A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2018 Reading Committee: Richard Ladner, Chair Alan Borning Katharina Reinecke Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Computer Science & Engineering University of Washington Abstract Expanding Information Access through Data-Driven Design Danielle Bragg Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Richard Ladner Computer Science & Engineering Computer scientists have made progress on many problems in information access: curating large datasets, developing machine learning and computer vision, building extensive networks, and designing powerful interfaces and graphics. However, we sometimes fail to fully leverage these modern techniques, especially when building systems inclusive of people with disabilities (who total a billion worldwide [168], and nearly one in five in the U.S. [26]). For example, visual graphics and small text may exclude people with visual impairments, and text-based resources like search engines and text editors may not fully support people using unwritten sign languages. In this dissertation, I argue that if we are willing to break with traditional modes of information access, we can leverage modern computing and design techniques from computer graphics, crowdsourcing, topic modeling, and participatory design to greatly improve and enrich access. This dissertation demonstrates this potential -

Guidelines and Standards for Tactile Graphics, 2010

Guidelines and Standards for Tactile Graphics, 2010 Developed as a Joint Project of the Braille Authority of North America and the Canadian Braille Authority L'Autorité Canadienne du Braille Published by The Braille Authority of North America ©2011 by The Braille Authority of North America All rights reserved. This material may be downloaded and printed, but not altered or sold. The mission and purpose of the Braille Authority of North America are to assure literacy for tactile readers through the standardization of braille and/or tactile graphics. BANA promotes and facilitates the use, teaching, and production of braille. It publishes rules, interprets, and renders opinions pertaining to braille in all existing codes. It deals with codes now in existence or to be developed in the future, in collaboration with other countries using English braille. In exercising its function and authority, BANA considers the effects of its decisions on other existing braille codes and formats; the ease of production by various methods; and acceptability to readers. For more information and resources, visit www.brailleauthority.org. ii Canadian Braille Authority (CBA) Members CNIB (Canadian National Institute for the Blind) Canadian Council of the Blind Braille Authority of North America (BANA) Members American Council of the Blind, Inc. (ACB) American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) American Printing House for the Blind (APH) Associated Services for the Blind (ASB) Association for Education & Rehabilitation of the Blind & Visually Impaired (AER) Braille Institute of America (BIA) California Transcribers & Educators for the Blind and Visually Impaired (CTEBVI) CNIB (Canadian National Institute for the Blind) The Clovernook Center for the Blind (CCBVI) National Braille Association, Inc. -

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

Nemeth Code Uses Some Parts of Textbook Format but Has Some Idiosyncrasies of Its Own

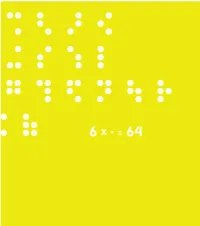

This book is a compilation of research, in “Understanding and Tracing the Problem faced by the Visually Impaired while doing Mathematics” as a Diploma project by Aarti Vashisht at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bangalore. 6 DOTS 64 COMBINATIONS A Braille character is formed out of a combination of six dots. Including the blank space, sixty four combinations are possible using one or more of these six dots. CONTENTS Introduction 2 About Braille 32 Mathematics for the Visually Impaired 120 Learning Mathematics 168 C o n c l u s i o n 172 P e o p l e a n d P l a c e s 190 Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION This project tries to understand the nature of the problems that are faced by the visually impaired within the realm of mathematics. It is a summary of my understanding of the problems in this field that may be taken forward to guide those individuals who are concerned about this subject. My education in design has encouraged interest in this field. As a designer I have learnt to be aware of my community and its needs, to detect areas where design can reach out and assist, if not resolve, a problem. Thus began, my search, where I sought to grasp a fuller understanding of the situation by looking at the various mediums that would help better communication. During the project I realized that more often than not work happened in individual pockets which in turn would lead to regionalization of many ideas and opportunities. Data collection got repetitive, which would delay or sometimes even hinder the process. -

Writing As Language Technology

HG2052 Language, Technology and the Internet Writing as Language Technology Francis Bond Division of Linguistics and Multilingual Studies http://www3.ntu.edu.sg/home/fcbond/ [email protected] Lecture 2 HG2052 (2021); CC BY 4.0 Overview ã The origins of writing ã Different writing systems ã Representing writing on computers ã Writing versus talking Writing as Language Technology 1 The Origins of Writing ã Writing was invented independently in at least three places: Mesopotamia China Mesoamerica Possibly also Egypt (Earliest Egyptian Glyphs) and the Indus valley. ã The written records are incomplete ã Gradual development from pictures/tallies Writing as Language Technology 2 Follow the money ã Before 2700, writing is only accounting. Temple and palace accounts Gold, Wheat, Sheep ã How it developed One token per thing (in a clay envelope) One token per thing in the envelope and marked on the outside One mark per thing One mark and a symbol for the number Finally symbols for names Denise Schmandt-Besserat (1997) How writing came about. University of Texas Press Writing as Language Technology 3 Clay Tokens and Envelope Clay Tablet Writing as Language Technology 4 Writing systems used for human languages ã What is writing? A system of more or less permanent marks used to represent an utterance in such a way that it can be recovered more or less exactly without the intervention of the utterer. Peter T. Daniels, The World’s Writing Systems ã Different types of writing systems are used: Alphabetic Syllabic Logographic Writing -

World Braille Usage, Third Edition

World Braille Usage Third Edition Perkins International Council on English Braille National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped Library of Congress UNESCO Washington, D.C. 2013 Published by Perkins 175 North Beacon Street Watertown, MA, 02472, USA International Council on English Braille c/o CNIB 1929 Bayview Avenue Toronto, Ontario Canada M4G 3E8 and National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., USA Copyright © 1954, 1990 by UNESCO. Used by permission 2013. Printed in the United States by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library of Congress, 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data World braille usage. — Third edition. page cm Includes index. ISBN 978-0-8444-9564-4 1. Braille. 2. Blind—Printing and writing systems. I. Perkins School for the Blind. II. International Council on English Braille. III. Library of Congress. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. HV1669.W67 2013 411--dc23 2013013833 Contents Foreword to the Third Edition .................................................................................................. viii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... x The International Phonetic Alphabet .......................................................................................... xi References ............................................................................................................................ -

General Codes to Know: Binary Ternary ASCII Morse Braille

General Codes to Know: ● Binary ● Ternary ● ASCII ● Morse ● Braille ● Semaphore ● NATO ● American Sign Language ● Pigpen ● International Maritime Signal Flags ● Caesar shift ● QWERTY ⇔ DVORAK ● Cryptogram ● Vigenere Cipher ● Book Cipher ● Playfair Cipher ● Chemical element numbers Useful sites: ● Onelook ● Quinapalus ● Rumkin Cipher Tools ● qhex ● Mapping Great Circles ● Quipqiup Behavioral Strategies: ● Make sure you have all the data for the puzzle. Ask yourself if you’re missing an entire page of the puzzle. ● If everything you’re doing feels right but you’re not getting gibberish, try asking yourself the following: am I ordering things correctly? (e.g. try columnmajor order instead of rowmajor order for a grid, try reading things in the reverse order, separate the letters into two groups and read the groups separately), ● If you’re working on a meta puzzle and are stuck, don’t have everyone stare at the same spreadsheet. Once the obvious work has been done and everyone’s tried working on it together for a while, have people duplicate the spreadsheet and try working on it individually without communicating their ideas. This leads to a greater variety of approaches being tried, increasing the chance of getting unstuck. ● If a puzzle requires shading in things to form a picture, coloring, or any visually precise work, do it in an image editing program such as GIMP. ● Don’t have multiple people work on easy puzzles. If one person is really excited to do a person, let him/her work on it alone. ● Identifying common puzzle elements: When you see… You should try... Small numbers (<= 26) Converting numbers to letters (1 = A, 2 = B, etc.) Smaller numbers (<= 15) Indexing the numbers into words in the puzzle (e.g.