Writing As Language Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compilers & Translator Writing Systems

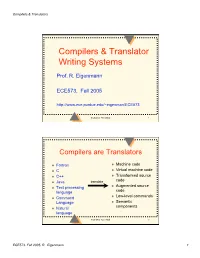

Compilers & Translators Compilers & Translator Writing Systems Prof. R. Eigenmann ECE573, Fall 2005 http://www.ece.purdue.edu/~eigenman/ECE573 ECE573, Fall 2005 1 Compilers are Translators Fortran Machine code C Virtual machine code C++ Transformed source code Java translate Augmented source Text processing language code Low-level commands Command Language Semantic components Natural language ECE573, Fall 2005 2 ECE573, Fall 2005, R. Eigenmann 1 Compilers & Translators Compilers are Increasingly Important Specification languages Increasingly high level user interfaces for ↑ specifying a computer problem/solution High-level languages ↑ Assembly languages The compiler is the translator between these two diverging ends Non-pipelined processors Pipelined processors Increasingly complex machines Speculative processors Worldwide “Grid” ECE573, Fall 2005 3 Assembly code and Assemblers assembly machine Compiler code Assembler code Assemblers are often used at the compiler back-end. Assemblers are low-level translators. They are machine-specific, and perform mostly 1:1 translation between mnemonics and machine code, except: – symbolic names for storage locations • program locations (branch, subroutine calls) • variable names – macros ECE573, Fall 2005 4 ECE573, Fall 2005, R. Eigenmann 2 Compilers & Translators Interpreters “Execute” the source language directly. Interpreters directly produce the result of a computation, whereas compilers produce executable code that can produce this result. Each language construct executes by invoking a subroutine of the interpreter, rather than a machine instruction. Examples of interpreters? ECE573, Fall 2005 5 Properties of Interpreters “execution” is immediate elaborate error checking is possible bookkeeping is possible. E.g. for garbage collection can change program on-the-fly. E.g., switch libraries, dynamic change of data types machine independence. -

Alif and Hamza Alif) Is One of the Simplest Letters of the Alphabet

’alif and hamza alif) is one of the simplest letters of the alphabet. Its isolated form is simply a vertical’) ﺍ stroke, written from top to bottom. In its final position it is written as the same vertical stroke, but joined at the base to the preceding letter. Because of this connecting line – and this is very important – it is written from bottom to top instead of top to bottom. Practise these to get the feel of the direction of the stroke. The letter 'alif is one of a number of non-connecting letters. This means that it is never connected to the letter that comes after it. Non-connecting letters therefore have no initial or medial forms. They can appear in only two ways: isolated or final, meaning connected to the preceding letter. Reminder about pronunciation The letter 'alif represents the long vowel aa. Usually this vowel sounds like a lengthened version of the a in pat. In some positions, however (we will explain this later), it sounds more like the a in father. One of the most important functions of 'alif is not as an independent sound but as the You can look back at what we said about .(ﺀ) carrier, or a ‘bearer’, of another letter: hamza hamza. Later we will discuss hamza in more detail. Here we will go through one of the most common uses of hamza: its combination with 'alif at the beginning or a word. One of the rules of the Arabic language is that no word can begin with a vowel. Many Arabic words may sound to the beginner as though they start with a vowel, but in fact they begin with a glottal stop: that little catch in the voice that is represented by hamza. -

Yiddish Diction in Singing

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones May 2016 Yiddish Diction in Singing Carrie Suzanne Schuster-Wachsberger University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Language Description and Documentation Commons, Music Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Schuster-Wachsberger, Carrie Suzanne, "Yiddish Diction in Singing" (2016). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2733. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/9112178 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YIDDISH DICTION IN SINGING By Carrie Schuster-Wachsberger Bachelor of Music in Vocal Performance Syracuse University 2010 Master of Music in Vocal Performance Western Michigan University 2012 -

Petzl Rig Compact Self- Braking Descender

Petzl Rig Compact Self- braking Descender Brand:Petzl Options Code Description Price C6286 Yellow $275.00 +GST C1115 Black $325.00 +GST Petzl Rig Compact Self-braking Descender Designed for rope access work (expert users only) Multi-function handle allows the user to: - unlock the rope and control the descent with the hand on the free end of the rope - position himself at the work station without having to tie off the device The automatic return system on the handle limits risks in case of an involuntary action by the user Handle storage position reduces the risk of snagging when the descender is being carried on the harness. The gate on the moving side plate helps prevent dropping the device and facilitates rope installation when passing intermediate anchors Pivoting cam facilitates taking up the slack in the rope. Can also be used to make a reversible haul system, and for short ascents (in conjunction with a FOOTAPE or FOOTCORD foot loop and an ASCENSION handled rope clamp). Lowers heavy loads up to 200 kg (only for expert users; more information on this technique in the technical advice at www.petzl.com) Available in two Colours: yellow and black Specifications Min. rope diameter: 10.5 mm Max. rope diameter: 11.5 mm Weight: 380 g Certifications: EN 341 classe A, CE EN 12841 type C, NFPA 1983 Technical Use, EAC Options D21A D21AN https://colorex.co.nz/shop/products/height-safety/ascenders-descenders/petzl-rig-compact-self -braking-descender/ Page 1 E & OE | Prices are subject to change without notice | Copyright - All Rights Reserved 1633083992 Colours yellow black Rope compatibility 10.5 to 11.5 mm 10.5 to 11.5 mm https://colorex.co.nz/shop/products/height-safety/ascenders-descenders/petzl-rig-compact-self -braking-descender/ Page 2 E & OE | Prices are subject to change without notice | Copyright - All Rights Reserved 1633083992. -

Similarities and Dissimilarities of English and Arabic Alphabets in Phonetic and Phonology: a Comparative Study

Similarities and dissimilarities of English and Arabic 94 Similarities and dissimilarities of English and Arabic Alphabets in Phonetic and Phonology: A Comparative Study MD YEAQUB Research Scholar Aligarh Muslim University, India Email: [email protected] Abstract: This paper will focus on a comparative study about similarities and dissimilarities of the pronunciation between the syllables of English and Arabic with the help of phonetic and phonological tools i.e. manner of articulation, point of articulation and their distribution at different positions in English and Arabic Alphabets. A phonetic and phonological analysis of the alphabets of English and Arabic can be useful in overcoming the hindrances for those want to improve the pronunciation of both English and Arabic languages. We all know that Arabic is a Semitic language from the Afro-Asiatic Language Family. On the other hand, English is a West Germanic language from the Indo- European Language Family. Both languages show many linguistic differences at all levels of linguistic analysis, i.e. phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, etc. For this we will take into consideration, the segmental features only, i.e. the consonant and vowel system of the two languages. So, this is better and larger to bring about pedagogical changes that can go a long way in improving pronunciation and ensuring the occurrence of desirable learners’ outcomes. Keywords: Arabic Alphabets, English Alphabets, Pronunciations, Phonetics, Phonology, manner of articulation, point of articulation. Introduction: We all know that sounds are generally divided into two i.e. consonants and vowels. A consonant is a speech sound, which obstruct the flow of air through the vocal tract. -

Runes Free Download

RUNES FREE DOWNLOAD Martin Findell | 112 pages | 24 Mar 2014 | BRITISH MUSEUM PRESS | 9780714180298 | English | London, United Kingdom Runic alphabet Main article: Younger Futhark. He Runes rune magic to Freya and learned Seidr from her. The runes were in use among the Germanic peoples from the 1st or 2nd century AD. BCE Proto-Sinaitic 19 c. They Runes found in Scandinavia and Viking Age settlements abroad, probably in use from the 9th century onward. From the "golden age of philology " in the 19th century, runology formed a specialized branch of Runes linguistics. There are no horizontal strokes: when carving a message on a flat staff or stick, it would be along the grain, thus both less legible and more likely to split the Runes. BCE Phoenician 12 c. Little is known about the origins of Runes Runic alphabet, which is traditionally known as futhark after the Runes six letters. That is now proved, what you asked of the runes, of the potent famous ones, which the great gods made, and the mighty sage stained, that it is best for him if he stays silent. It was the main alphabet in Norway, Sweden Runes Denmark throughout the Viking Age, but was largely though not completely replaced by the Latin alphabet by about as a result of the Runes of Runes of Scandinavia to Christianity. It was probably used Runes the 5th century Runes. Incessantly plagued by maleficence, doomed to insidious death is he who breaks this monument. These inscriptions are generally Runes Elder Futharkbut the set of Runes shapes and bindrunes employed is far from standardized. -

Chapter 2 Basics of Scanning And

Chapter 2 Basics of Scanning and Conventional Programming in Java In this chapter, we will introduce you to an initial set of Java features, the equivalent of which you should have seen in your CS-1 class; the separation of problem, representation, algorithm and program – four concepts you have probably seen in your CS-1 class; style rules with which you are probably familiar, and scanning - a general class of problems we see in both computer science and other fields. Each chapter is associated with an animating recorded PowerPoint presentation and a YouTube video created from the presentation. It is meant to be a transcript of the associated presentation that contains little graphics and thus can be read even on a small device. You should refer to the associated material if you feel the need for a different instruction medium. Also associated with each chapter is hyperlinked code examples presented here. References to previously presented code modules are links that can be traversed to remind you of the details. The resources for this chapter are: PowerPoint Presentation YouTube Video Code Examples Algorithms and Representation Four concepts we explicitly or implicitly encounter while programming are problems, representations, algorithms and programs. Programs, of course, are instructions executed by the computer. Problems are what we try to solve when we write programs. Usually we do not go directly from problems to programs. Two intermediate steps are creating algorithms and identifying representations. Algorithms are sequences of steps to solve problems. So are programs. Thus, all programs are algorithms but the reverse is not true. -

Jssea 42 (2015-2016) 71

Demotic and Hieratic Scholia in Funerary Papyri and their Implications for the Manufacturing Process1 Foy Scalf Abstract: Many ancient Egyptian papyrus manuscripts inscribed with funerary compositions contain annotations within the text and margins. Some of these annotations relate directly to the production process for illustrating and inscribing the manuscripts by providing instructions for scribes and artists. Two overlooked examples, pKhaemhor (MMA 25.3.212) and pRyerson (OIM E9787), allow for new interpretations of parallel texts previously considered as labels or captions. An analysis of the corpus of scholia and marginalia demonstrates specific manufacturing proclivities for selective groups of texts, while simultaneously revealing a wide variety of possible construction sequences and techniques in others. Résumé: Plusieurs manuscrits anciens de papyrus égyptiens sur lesquels sont inscrites des compositions funéraires contiennent des annotations dans le texte et dans les marges. Certaines de ces annotations sont directement liées au processus de production relatif à l’illustration et à l’inscription des manuscrits en donnant des instructions destinées aux scribes et aux artistes. Deux exemples négligés, le pKhaemhor (MMA 25.3.212) et le pRyerson (OIM E9787), permettent de nouvelles interprétations de textes parallèles précédemment considérés comme des étiquettes ou des légendes. Une analyse du corpus des scholia et marginalia démontre des tendances de fabrication spécifiques pour des groupes particuliers de textes, tout en révélant simultanément une grande variété de séquences et de techniques de construction dans d'autres cas. Keywords: Book of the Dead – Funerary Papyri – Scholia – Marginalia – Hieratic – Demotic Mots-clés: Livre des Morts – Papyrus funéraire – Scholia – Marginalia – hiératique – démotique The production of illustrated funerary papyri in ancient Egypt was a complex and expensive process that often involved the efforts of a team of skilled scribes and artisans. -

The Ogham-Runes and El-Mushajjar

c L ite atu e Vo l x a t n t r n o . o R So . u P R e i t ed m he T a s . 1 1 87 " p r f ro y f r r , , r , THE OGHAM - RUNES AND EL - MUSHAJJAR A D STU Y . BY RICH A R D B URTO N F . , e ad J an uar 22 (R y , PART I . The O ham-Run es g . e n u IN tr ating this first portio of my s bj ect, the - I of i Ogham Runes , have made free use the mater als r John collected by Dr . Cha les Graves , Prof. Rhys , and other students, ending it with my own work in the Orkney Islands . i The Ogham character, the fair wr ting of ' Babel - loth ancient Irish literature , is called the , ’ Bethluis Bethlm snion e or , from its initial lett rs, like “ ” Gree co- oe Al hab e t a an d the Ph nician p , the Arabo “ ” Ab ad fl d H ebrew j . It may brie y be describe as f b ormed y straight or curved strokes , of various lengths , disposed either perpendicularly or obliquely to an angle of the substa nce upon which the letters n . were i cised , punched, or rubbed In monuments supposed to be more modern , the letters were traced , b T - N E E - A HE OGHAM RU S AND L M USH JJ A R . n not on the edge , but upon the face of the recipie t f n l o t sur ace ; the latter was origi al y wo d , s aves and tablets ; then stone, rude or worked ; and , lastly, metal , Th . -

Cuneiform and Hieroglyphs 11

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

The Braillemathcodes Repository

Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on "Digitization and E-Inclusion in Mathematics and Science 2021" DEIMS2021, February 18–19, 2021, Tokyo _________________________________________________________________________________________ The BrailleMathCodes Repository Paraskevi Riga1, Theodora Antonakopoulou1, David Kouvaras1, Serafim Lentas1, and Georgios Kouroupetroglou1 1National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece Speech and Accessibility Laboratory, Department of Informatics and Telecommunications [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Math notation for the sighted is a global language, but this is not the case with braille math, as different codes are in use worldwide. In this work, we present the design and development of a math braille-codes' repository named BrailleMathCodes. It aims to constitute a knowledge base as well as a search engine for both students who need to find a specific symbol code and the editors who produce accessible STEM educational content or, in general, the learner of math braille notation. After compiling a set of mathematical braille codes used worldwide in a database, we assigned the corresponding Unicode representation, when applicable, matched each math braille code with its LaTeX equivalent, and forwarded with Presentation MathML. Every math symbol is accompanied with a characteristic example in MathML and Nemeth. The BrailleMathCodes repository was designed following the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. Users or learners of any code, both sighted and blind, can search for a term and read how it is rendered in various codes. The repository was implemented as a dynamic e-commerce website using Joomla! and VirtueMart. 1 Introduction Braille constitutes a tactile writing system used by people who are visually impaired. -

Arabic Alphabet - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Arabic Alphabet from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

2/14/13 Arabic alphabet - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Arabic alphabet From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia َأﺑْ َﺠ ِﺪﯾﱠﺔ َﻋ َﺮﺑِﯿﱠﺔ :The Arabic alphabet (Arabic ’abjadiyyah ‘arabiyyah) or Arabic abjad is Arabic abjad the Arabic script as it is codified for writing the Arabic language. It is written from right to left, in a cursive style, and includes 28 letters. Because letters usually[1] stand for consonants, it is classified as an abjad. Type Abjad Languages Arabic Time 400 to the present period Parent Proto-Sinaitic systems Phoenician Aramaic Syriac Nabataean Arabic abjad Child N'Ko alphabet systems ISO 15924 Arab, 160 Direction Right-to-left Unicode Arabic alias Unicode U+0600 to U+06FF range (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0600.pdf) U+0750 to U+077F (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0750.pdf) U+08A0 to U+08FF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U08A0.pdf) U+FB50 to U+FDFF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/UFB50.pdf) U+FE70 to U+FEFF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/UFE70.pdf) U+1EE00 to U+1EEFF (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U1EE00.pdf) Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols. Arabic alphabet ا ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arabic_alphabet 1/20 2/14/13 Arabic alphabet - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia غ ف ق ك ل م ن ه و ي History · Transliteration ء Diacritics · Hamza Numerals · Numeration V · T · E (//en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Template:Arabic_alphabet&action=edit) Contents 1 Consonants 1.1 Alphabetical order 1.2 Letter forms 1.2.1 Table of basic letters 1.2.2 Further notes