Recognizing German Dialects by Prosodic Features Alone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Assignment of Grammatical Gender in German: Testing Optimal Gender Assignment Theory

The Assignment of Grammatical Gender in German: Testing Optimal Gender Assignment Theory Emma Charlotte Corteen Trinity Hall September 2018 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The Assignment of Grammatical Gender in German: Testing Optimal Gender Assignment Theory Emma Charlotte Corteen Abstract The assignment of grammatical gender in German is a notoriously problematic phenomenon due to the apparent opacity of the gender assignment system (e.g. Comrie 1999: 461). Various models of German gender assignment have been proposed (e.g. Spitz 1965, Köpcke 1982, Corbett 1991, Wegener 1995), but none of these is able to account for all of the German data. This thesis investigates a relatively under-explored, recent approach to German gender assignment in the form of Optimal Gender Assignment Theory (OGAT), proposed by Rice (2006). Using the framework of Optimality Theory, OGAT claims that the form and meaning of a noun are of equal importance with respect to its gender. This is formally represented by the crucial equal ranking of all gender assignment constraints in a block of GENDER FEATURES, which is in turn ranked above a default markedness hierarchy *NEUTER » *FEMININE » *MASCULINE, which is based on category size. A key weakness of OGAT is that it does not specify what constitutes a valid GENDER FEATURES constraint. This means that, in theory, any constraint can be proposed ad hoc to ensure that an OGAT analysis yields the correct result. In order to prevent any constraints based on ‘postfactum rationalisations’ (Comrie 1999: 461) from being included in the investigation, the GENDER FEATURES constraints which have been proposed in the literature for German are assessed according to six criteria suggested by Enger (2009), which seek to determine whether there is independent evidence for a GENDER FEATURES constraint. -

Version 6.0.0

Codebook Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Survey in 4 European Countries – Germany Wave 8 Release version: 6.0.0 Release date: 30 July 2021 Citation: CILS4EU-DE. 2021. Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Survey in Four European Countries – Germany. Codebook. Wave 8 – 2020, v6.0.0. Mannheim: Mannheim University. 1 Content 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 4 2 Variable overview ................................................................................................................................. 6 2.1 Ordered by topic .......................................................................................................................... 6 2.1.1 Tracking data set ..................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1.2 Youth main questionnaire ..................................................................................................................... 9 2.1.3 Youth siblings questionnaire ...............................................................................................................19 2.1.4 Youth residence history calendar .......................................................................................................23 2.2 Ordered by questionnaire ......................................................................................................... 25 2.2.1 Tracking data set ...................................................................................................................................25 -

FCG Background-Paper

FINANCE AND THE COMMON GOOD Background paper for the joint Socires & Sustainable Finance Lab programme (2019-2021) April 2019 Abstract In this three-year programme (2019-2021), Socires and the Sustainable Finance Lab (SFL) explore the feasibility of an alternative arrangement for the financial sector; a financial sector that fruitfully interacts with state and society, together setting goals for finance in service of’ the common good. Why is this necessary? In the past few decades, the ‘logic of finance’ has increasingly nestled itself in all domains of modern societies, crowding out other motives and relational modes for interaction; a phenomenon aptly referred to as ‘financialisation’. Now, with the 2008 financial crisis still fresh in our minds, and other crises - ecological, social and (geo-)political - unfolding before our eyes, research into alternative ways of economic and financial organisation is long overdue. We believe that the countries of the former ‘Rhineland’ - Benelux, Germany and France - still stand in a societal tradition that could be the breeding ground for a fruitful new arrangement between finance, state and society, one in which transactions are embedded in relations. As there is no possibility of dictating this kind of change to any one of the actors involved, we aim to generate such commitment by engaging in high-level dialogue with the relevant stakeholders from the Rhinelandic area. This programme has four pillars – 1) Organising for finance for the common good, 2) Young Professionals programme, 3) International conferences and 4) Working tables - in which different activities are developed, involving both experienced decision makers as well as promising young professionals. -

Burghers As Cultural Agents in the Low Countries and the Empire

Burghers as Cultural Agents in the Low Countries and the Empire VON WIM BLOCKMANS The general theme of this volume, Germany and Western Europe, leaves open the question whether we shall deal with comparisons or with influences. In some cases of particular cul tural achievements such as the production of a manuscript or the construction of a major building, it may be possible to identify the intellectual authors and artists, to follow their movements and to compare their products. When we think of more encompassing pro cesses such as the dissemination of types of governance or the use of written documents, it becomes much more difficult to point to causes and effects. We will first have to clarify which phenomena we consider to be crucial, to observe the timing of their appearance and impact, before it becomes possible to compare these data and to try and look for influences. Even then, it remains an open question if the phenomena under consideration were really linked, since they might have appeared simultaneously or in succession without any causal relation. If we are looking for cultural transfers through space and time, its general conditions should be kept in mind: we need communication, mobility and the willingness to adopt dif ferent practices. None of these preconditions is selfevident; on the other hand, the intens ity of communication and mobility, and a tradition of openness enhance the probability of transfers. Adoption mostly requires adaptation in order to incorporate innovations into another cultural universe. This mental attitude presupposes interaction, curiosity and the preparedness to change established traditions. -

Texas Alsatian

2017 Texas Alsatian Karen A. Roesch, Ph.D. Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Indianapolis, Indiana, USA IUPUI ScholarWorks This is the author’s manuscript: This is a draft of a chapter that has been accepted for publication by Oxford University Press in the forthcoming book Varieties of German Worldwide edited by Hans Boas, Anna Deumert, Mark L. Louden, & Péter Maitz (with Hyoun-A Joo, B. Richard Page, Lara Schwarz, & Nora Hellmold Vosburg) due for publication in 2016. https://scholarworks.iupui.edu Texas Alsatian, Medina County, Texas 1 Introduction: Historical background The Alsatian dialect was transported to Texas in the early 1800s, when entrepreneur Henri Castro recruited colonists from the French Alsace to comply with the Republic of Texas’ stipulations for populating one of his land grants located just west of San Antonio. Castro’s colonization efforts succeeded in bringing 2,134 German-speaking colonists from 1843 – 1847 (Jordan 2004: 45-7; Weaver 1985:109) to his land grants in Texas, which resulted in the establishment of four colonies: Castroville (1844); Quihi (1845); Vandenburg (1846); D’Hanis (1847). Castroville was the first and most successful settlement and serves as the focus of this chapter, as it constitutes the largest concentration of Alsatian speakers. This chapter provides both a descriptive account of the ancestral language, Alsatian, and more specifically as spoken today, as well as a discussion of sociolinguistic and linguistic processes (e.g., use, shift, variation, regularization, etc.) observed and documented since 2007. The casual observer might conclude that the colonists Castro brought to Texas were not German-speaking at all, but French. -

German Dialects in Kansas and Missouri Scholarworks User Guide August, 2020

German Dialects in Kansas and Missouri ScholarWorks User Guide August, 2020 Table of Contents INTERVIEW METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................. 1 THE RECORDINGS ................................................................................................................................................. 2 THE SPEAKERS ...................................................................................................................................................... 2 KANSAS ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 MISSOURI .................................................................................................................................................................... 4 THE QUESTIONNAIRES ......................................................................................................................................... 5 WENKER SENTENCES ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 KU QUESTIONNAIRE ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 REFERENCE MAPS FOR LOCATING POTENTIAL SPEAKERS ..................................................................................... -

Hunsrik-Xraywe.!A!New!Way!In!Lexicography!Of!The!German! Language!Island!In!Southern!Brazil!

Dialectologia.!Special-issue,-IV-(2013),!147+180.!! ISSN:!2013+2247! Received!4!June!2013.! Accepted!30!August!2013.! ! ! ! ! HUNSRIK-XRAYWE.!A!NEW!WAY!IN!LEXICOGRAPHY!OF!THE!GERMAN! LANGUAGE!ISLAND!IN!SOUTHERN!BRAZIL! Mateusz$MASELKO$ Austrian$Academy$of$Sciences,$Institute$of$Corpus$Linguistics$and$Text$Technology$ (ICLTT),$Research$Group$DINAMLEX$(Vienna,$Austria)$ [email protected]$ $ $ Abstract$$ Written$approaches$for$orally$traded$dialects$can$always$be$seen$controversial.$One$could$say$ that$there$are$as$many$forms$of$writing$a$dialect$as$there$are$speakers$of$that$dialect.$This$is$not$only$ true$ for$ the$ different$ dialectal$ varieties$ of$ German$ that$ exist$ in$ Europe,$ but$ also$ in$ dialect$ language$ islands$ on$ other$ continents$ such$ as$ the$ Riograndese$ Hunsrik$ in$ Brazil.$ For$ the$ standardization$ of$ a$ language$ variety$ there$ must$ be$ some$ determined,$ general$ norms$ regarding$ orthography$ and$ graphemics.!Equipe!Hunsrik$works$on$the$standardization,$expansion,$and$dissemination$of$the$German$ dialect$ variety$ spoken$ in$ Rio$ Grande$ do$ Sul$ (South$ Brazil).$ The$ main$ concerns$ of$ the$ project$ are$ the$ insertion$of$Riograndese$Hunsrik$as$official$community$language$of$Rio$Grande$do$Sul$that$is$also$taught$ at$school.$Therefore,$the$project$team$from$Santa$Maria$do$Herval$developed$a$writing$approach$that$is$ based$on$the$Portuguese$grapheme$inventory.$It$is$used$in$the$picture$dictionary! Meine!ëyerste!100! Hunsrik! wërter$ (2010).$ This$ article$ discusses$ the$ picture$ dictionary$ -

Yiddish and Relation to the German Dialects Bryan Witmore University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 6-30-2016 Yiddish and Relation To The German Dialects Bryan Witmore University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the German Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Witmore, B.(2016). Yiddish and Relation To The German Dialects. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ etd/3522 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YIDDISH AND ITS RELATION TO THE GERMAN DIALECTS by Bryan Witmore Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina, 2006 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in German College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2016 Accepted by: Kurt Goblirsch, Director of Thesis Lara Ducate, Reader Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Bryan Witmore, 2016 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis project was made possible in large part by the German program at the University of South Carolina. The technical assistance that propelled this project was contributed by the staff at the Ted Mimms Foreign Language Learning Center. My family was decisive in keeping me physically functional and emotionally buoyant through the writing process. Many thanks to you all. iii ABSTRACT In an attempt to balance the complex, multi-component nature of Yiddish with its more homogenous speech community – Ashekenazic Jews –Yiddishists have proposed definitions for the Yiddish language that cannot be considered linguistic in nature. -

INTELLIGIBILITY of STANDARD GERMAN and LOW GERMAN to SPEAKERS of DUTCH Charlotte Gooskens1, Sebastian Kürschner2, Renée Van Be

INTELLIGIBILITY OF STANDARD GERMAN AND LOW GERMAN TO SPEAKERS OF DUTCH Charlotte Gooskens 1, Sebastian Kürschner 2, Renée van Bezooijen 1 1University of Groningen, The Netherlands 2 University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This paper reports on the intelligibility of spoken Low German and Standard German for speakers of Dutch. Two aspects are considered. First, the relative potential for intelligibility of the Low German variety of Bremen and the High German variety of Modern Standard German for speakers of Dutch is tested. Second, the question is raised whether Low German is understood more easily by subjects from the Dutch-German border area than subjects from other areas of the Netherlands. This is investigated empirically. The results show that in general Dutch people are better at understanding Standard German than the Low German variety, but that subjects from the border area are better at understanding Low German than subjects from other parts of the country. A larger amount of previous experience with the German standard variety than with Low German dialects could explain the first result, while proximity on the sound level could explain the second result. Key words Intelligibility, German, Low German, Dutch, Levenshtein distance, language contact 1. Introduction Dutch and German originate from the same branch of West Germanic. In the Middle Ages these neighbouring languages constituted a common dialect continuum. Only when linguistic standardisation came about in connection with nation building did the two languages evolve into separate social units. A High German variety spread out over the German language area and constitutes what is regarded as Modern Standard German today. -

Alsace and Its Language

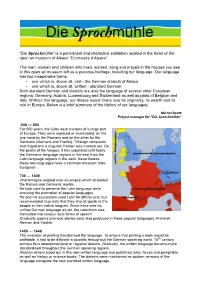

“Die Sproch mühle” is a permanent and interactive exhibition located in the heart of the open air museum of Alsace “Ecomusée d’Alsace”. The men, women and children who lived, worked, sang and prayed in the houses you see in this open air museum left us a precious heritage, including our language. Our language has two inseparable forms: • one which is, above all, oral - the German dialects of Alsace • one which is, above all, written - standard German Both standard German and dialects are also the language of several other European regions: Germany, Austria, Luxembourg and Switzerland as well as parts of Belgium and Italy. Without this language, our Alsace would finally lose its originality, its wealth and its role in Europe. Below is a brief summary of the history of our languages. Michel Bentz Project manager for “Die Sproch mühle“ -500 — 800 For 500 years, the Celts were masters of a large part of Europe. They were replaced or assimilated, on the one hand by the Romans and on the other by the Germans (Alemans and Franks). Through conquests and migrations a linguistic frontier was marked out. On the peaks of the Vosges, it has separated until today the Germanic language regions in the east from the Latin language regions in the west. Nevertheless, these two languages have a common ancestor: Indo- European. 700 — 1400 Charlemagne reigned over an empire which straddled the Roman and Germanic worlds. He took care to preserve the Latin language while ensuring the promotion of popular languages. He and his successors used Latin for official acts, but recommended to priests that they should speak to the people in their native tongues. -

1 Introduction

Notes 1 Introduction 1. A note on terminology: In this study the term ‘Austria’ will be used in order to refer to the German-speaking part of the Habsburg Empire (includ- ing ‘Vorderösterreich’) in the eighteenth century. At the time the Habsburg Emperors were also ruling the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. The German-speaking part of this nation may therefore be subdivided into and labelled ‘Austria’ and ‘Germany’. 2. Note that the inflectional subjunctive was taken over by the periphrastic form würde in German, which cannot be labelled a modal auxiliary verb. 3. Guchmann and Semenjuk did however notice ‘Präteritumschwund’ (loss of preterite forms) in the southern German area in the seventeenth and the beginning of the eighteenth century (see Guchmann and Semenjuk, 1981, p. 256), a development that can be observed in Austrian German in the eighteenth century (see Chapter 5). 4. ARCHER-3 = A Representative Corpus of Historical English Registers 3. 1990– 1993/2002/2007. Compiled under the supervision of Douglas Biber and Edward Finegan at Northern Arizona University, University of Southern California, University of Freiburg, University of Heidelberg, University of Helsinki, Uppsala University, University of Michigan, and University of Manchester. 5. See this website for details: http://www.llc.manchester.ac.uk/research/ projects/germanc/ 6. Fitzmaurice, for instance, carried out investigations on the use of relative markers (2000) and modal auxiliaries and lexically explicit stance expres- sions (2003) by Joseph Addison and his social network. Social network theory was originally developed as a research tool in the social sciences from where it was adopted into socio-linguistics. -

SOEP-IS 2018—ILANGUAGE: Variables from Innovative Language Modules

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics DIW Berlin / SOEP (Ed.) Research Report SOEP-IS 2018 - ILANGUAGE: Variables from innovative language modules SOEP Survey Papers, No. 851 Provided in Cooperation with: German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin) Suggested Citation: DIW Berlin / SOEP (Ed.) (2020) : SOEP-IS 2018 - ILANGUAGE: Variables from innovative language modules, SOEP Survey Papers, No. 851, Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW), Berlin This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/219075 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative