Canada-Co-Operative-Province.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The U.F.A. Who Is Interested in the States Power Trust

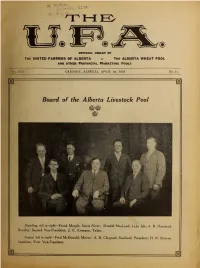

M. WcRae, ... pederal, Alta. OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE UNITED FARMERS OF ALBERTA THE ALBERTA WHEAT POOL AND OTHER PROVINCIAL MARKETING POOLS Vol. VIII. CALGARY, ALBERTA, APRIL 1st, 1929 No. 11. m Board of the Alberta Livestock Pool Standing, left to r/gA/—Frank Marple. Spirit River; Donald MacLeod, Lake Isle; A. B. Haarstad, Bentley. Second Vice-President; J. E, Evenson, Taber. Seated, left to right—Fred McDonald. Mirror; A. B. Claypool, Swalwell. President; H. N. Stearns. Innisfree, First Vice-President. 2 rsw) THE U. F. A. April iBt, lyz^i Ct The Weed-Killing CULTIVATOR with the exclusive Features The Climax Cultivator leads the war on weeds that trob these Provinces of $60,000,000 every year. Put it to work for you! Get the extra profits it is ready to make for you—clean grain, more grain, more money. The Climax has special featxires found in no Sold in Western Canada by other cultivator. Hundreds of owners acclaim it Cockshutt Plow Co., as a durable, dependable modem machine. Limited The Climax is made to suit every type of farm Winnipeg, Regina, and any kind of power. great variety of equip- Saskatoon, Calgary, A Edmonton ment for horses or tractors. Special Features of the Climax Manufactured by The Patented Depth Regulator saves The Frost & Wood Co., Limited pow«r and horse fag. The Power Lift saves time. Points working independ- Smiths Falls, Oat. ently do better work. Heavy Duty Drag Bars equipped with powerful coils prings prevent breakage. Rigid Angle Steel Frame. Variety of points from 2" to 14". llVi" points are standard eqvdpment. -

Grain Elevators in Canada, As at August 1, 1998

Grain Elevators Silos à grains du in Canada Canada Crop year Campagne agricole 1998 - 1999 1998 - 1999 As at August 1, 1998 Au 1er août 1998 www.grainscanada.gc.ca © Canadian Grain Commission © Commission canadienne des grains TABLE OF CONTENTS Table 1 - Summary - All Elevators, By Province, Rail And Class Of Licence Table 2 - List Of Companies And Individuals Licensed Table 3 - Licensed Terminal Elevators Table 4 - Licensed Transfer Elevators Table 5 - Licensed Process Elevators Table 6 - Licensed Primary Elevator Storage Capacity, By Firms Table 7 - Licensed Grain Dealers Table 8 - Summary Of "Operating Units", By Province And Company Table 9 - Summary, Country Shipping Points And Licensed Primary Elevators Table 10 - Off-Line Elevators Situated In The Western Division Table 11 - All Elevators, By Stations - Manitoba - Saskatchewan - Alberta - British Columbia - Ontario - Quebec - Nova Scotia Appendix - Historical Record - All Elevators © Canadian Grain Commission © Commission canadienne des grains TABLE DES MATIÈRES Tableau 1 - Résumé - Tous les silos, par province, voie ferrée et catégorie de licence Tableau 2 - Liste des compagnies et des particuliers agréés Tableau 3 - Silos terminaux agréés Tableau 4 - Silos de transbordement agréés Tableau 5 - Silos de transformation agréés Tableau 6 - Capacité d'entreposage des silos primaires agréés, par compagnie Tableau 7 - Négociants en grains titulaires d'une licence Tableau 8 - Résumé des «Unités d'exploitation», par province et compagnie Tableau 9 - Résumé, Points d'expédition régionaux -

Fall 2007 (PDF)

Saskatchewan flax G r o w e r Chair’s Report What a difference a year can make!! The Commission is sponsoring a straw The Canadian dollar is at par! Agriculture has gone management workshop on February 12 and 13, from where governments are not interested in basic Allen Kuhlmann 2008. Green people are aiming their sights on fire Chair, research (because we only grow commodities which – learn how not to burn straw and maybe make Saskatchewan Flax Development are in surplus) to where prices have exploded on a buck. As a result of the environmental concerns Commission many of those same commodities. Nations are block- the Commission will continue working with the Ag ing exports to protect domestic food supplies and Environmental Group to modify farm practices. importing no matter what the cost. WOW! I wonder if Read more regarding this in the following pages. those in Ottawa and elsewhere that fund agronomic After a very long wait and much pain to dial Our Mission research have noticed? up internet users, we have a brand new website: “To lead, promote, How high would those prices be if the Canadian www.saskflax.com. Check it out if you haven’t dollar was .65 or .80? Interesting times for sure! I already. and enhance the hope this optimism and good times survive longer Areas where I have traveled suggest flax production, than higher input costs! yields didn’t suffer as much as some other crops. value-added Now to more mundane but also important I hope this was the case on your farm. -

Corporate Greed Does Not Spare Cooperatives: Chronicle of the Disappearance of the Largest Agri-Food Cooperative in Canada by Assoumou-Ndong, Franklin

Corporate greed does not spare cooperatives: chronicle of the disappearance of the largest agri-food cooperative in Canada by Assoumou-Ndong, Franklin Global and diverse cooperative enterprise, Saskatchewan Wheat Pool (SWP), now known as Viterra Inc., has been ranked for years among the 50 largest companies in Canada, including the first in the handling and distribution of grain and also the largest agri-food cooperative in the country. It was the pride of an entire province. Supporters of the cooperative model present it as an alternative model for excellence in business, based on a human vision of enterprises focused on community empowerment and democracy. In the late 1800s, after years of battle and frustration against government policies of capitalism’s free market in agriculture, farmers in western Canada understood the need to regroup, precisely in cooperatives, to counter the harmful effects of free market and speculative fluctuations in grain prices. Cooperation appeared then as an alternative to economic and social exploitation of the people, especially in rural communities. Cooperatives were becoming tools for social change to support members (or community) and the redistribution of economic power. In June 1924, nearly 46 000 farmers, producing mainly wheat, officially signed a new contract that united them under the banner of Saskatchewan Cooperative Wheat Producers Ltd . (incorporated in 1923); the cooperative was subsequently renamed (in 1953) the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool . The cooperative has gone through many difficult times, such as the Great Depression of the 1930s, and has had good years with instances of record operating surplus (profits) and healthy membership numbers of farmer members (Assoumou-Ndong, 2001a; Lang, 2007). -

ARCHIVES and SPECIAL COLLECTIONS QUEEN ELIZABETH II LIBRARY MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY, ST

ARCHIVES and SPECIAL COLLECTIONS QUEEN ELIZABETH II LIBRARY MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY, ST. JOHN'S, NL Royal Commission on Canada's Economic Prospects, 1956 COLL-030 Website: Archives and Special Collections Author: Linda White Date: 2009 Scope and Content: Briefs and related exhibits submitted to the Royal Commission on Canada's Economic Prospects of which Dr. Gushue was a member. Drafts of preliminary and final reports, studies commissioned and other working papers. President of Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1952-1966, thereafter President Emeritus. Custodial History: Office of the President, Memorial University of Newfoundland,|d1983. Gift. Restrictions: There are no restrictions on access. Copyright laws and regulations may apply to all or to parts of this collection. All patrons should be aware that copyright regulations state that any copy of archival material is to be used solely for the purpose of research or private study. Any use of the copy for any other purpose may require the authorization of the copyright owner. It is the patron's responsibility to obtain such authorization. 1.0 Royal Commission on Canada's Economic Prospects, 1956 1.01 Royal Commission on Canada's Economic Prospects, 1956, Submissions 1.01.001 Ex. 1 Royal Commission on Canada's Economic Prospects List of submissions received 1.01.002 Ex. 2 City of Halifax 1.01.003 Ex. 3 Nova Scotia Light and Power Company, Limited 1.01.004 Ex. 4 Government of the Province of Nova Scotia 1.01.005 Ex. 5 Nova Scotia Federation of Agriculture 1.01.006 Ex. 6 Nova Scotia Fruit Growers' Association 1.01.007 Ex. -

Paul Earl. "Lessons for Cooperatives in Transition: the Case of Western Canada's United Grain Growers

Journal of Cooperatives Volume 23 2009 Page 20-39 Lessons for Cooperatives in Transition: The Case of Western Canada’s United Grain Growers and Agricore United Paul D. Earl∗ ∗University of Manitoba, [email protected] Lessons for Cooperatives in Transition: The Case of Western Canada’s United Grain Growers and Agricore United Paul D. Earl This paper explores the takeover of Agricore United (AU) by Saskatchewan Wheat Pool, now known as Viterra. AU’s predecessor, United Grain Growers, was a “pure” cooperative that had issued limited voting shares, but was legally defined as consisting of members and shareholders. The paper argues that members should have been consulted about the transaction. The paper draws six lessons that for- merly “pure” cooperatives like AU, should observe to prevent being absorbed by a publicly held firm. It argues that hybrid organizations like AU can successfully resist a takeover bid if properly prepared. Introduction United Grain Growers (UGG) was formed in 1906 as the Grain Growers Grain Company (GGGC), but altered its name in 1917 after a merger with the Alberta Farmers Cooperative Elevator Company (AFCEC). It operated as UGG until 2001, when it merged with Agricore, which had been formed by a merger between Al- berta Wheat Pool (AWP) and Manitoba Pool Elevators (MPE), and became known as Agricore United (AU). In November 2006, it was subject to a hostile and ulti- mately successful takeover bid from the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool (SWP), which, by this time, had converted from a cooperative to a shareholder-controlled Canada Business Corporation Act (CBCA) company. The takeover was completed in June 2007. -

Cognition, Agency Theory and Organizational Failure: a Saskatchewan Wheat Pool Case Study

COGNITION, AGENCY THEORY AND ORGANIZATIONAL FAILURE: A SASKATCHEWAN WHEAT POOL CASE STUDY A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science In the Department of Agricultural Economics University of Saskatchewan by Katherine Alice Lang © Katherine Alice Lang, December 2006. All Rights Reserved. The author has agreed that the University of Saskatchewan and its library may make this thesis freely available for inspection. The author further has agreed that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised the thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or Dean of the College in which the thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without the author’s permission. It is also understood that due recognition will be given to the author of this thesis and the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use of the material in this thesis. Request for permission to copy or make other use of the material in this thesis in whole or in part should be addressed to: Department Head Department of Agricultural Economics 51 Campus Drive, Room 3D34 University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Canada, S7N 5A8 i ABSTRACT Lang, Katherine A. M.Sc. University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, December 2006. Cognition, Agency Theory and Organizational Failure: A Saskatchewan Wheat Pool Case Study. Supervisor: Dr. Murray E. Fulton The Saskatchewan Wheat Pool went from being the largest grain handler in western Canada in the mid 1990s to undertaking a $405 million debt restructuring in January 2003. -

Third Quarter Report of the Monitor – Canadian Grain Handling and Transportation System

Third Quarter Report 2012-2013 Crop Year Monitoring the Canadian Grain Handling and Transportation System ii Third Quarter Report of the Monitor – Canadian Grain Handling and Transportation System Quorum Corporation Suite 701, 9707–110 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5K 2L9 Telephone: 780 / 447-2111 Fax: 780 / 451-8710 Website: www.quorumcorp.net Email: [email protected] Members of the Quorum Corporation Advisory Board Mark A. Hemmes Chairman of the Advisory Board President, Quorum Corporation Edmonton, Alberta J. Marcel Beaulieu Director – Research and Analysis, Quorum Corporation Sherwood Park, Alberta Richard B. Boyd Senior Vice President, Canadian National Railway Company (retired) Kelowna, British Columbia A. Bruce McFadden Director – Research and Analysis, Quorum Corporation Edmonton, Alberta Shelley J. Thompson President, SJT Solutions Southey, Saskatchewan Members of the Grain Monitoring Team Mark Hemmes President Marcel Beaulieu Director – Research and Analysis Bruce McFadden Director – Research and Analysis Vincent Roy Senior Technical Officer Additional copies of this report may be downloaded from the Quorum Corporation website. 2012-2013 Crop Year iii Foreword The following report details the performance of Canada’s Grain Handling and Transportation System (GHTS) for the nine months ended 30 April 2013, and focuses on the various events, issues and trends manifest in the movement of Western Canadian grain during the first three quarters of the 2012-13 crop year. As with the Monitor’s previous quarterly and annual reports, the -

Saskatchewan Wheat Pool

International Food and Agribusiness Management Review Volume 7, Issue 3, 2004 Saskatchewan Wheat Pool Marv Painter aL a Associate Professor, Department of Management and Marketing, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Abstract In 1996, Saskatchewan Wheat Pool embarked on a strategy for growth and diversification by significantly expanding its asset base. This expansion brought with it many new costs, especially new fixed costs such as interest and depreciation. They failed to achieve the new revenues needed to support the higher fixed costs and consequently, found themselves in financial distress. In 2000, Mayo Schmidt was brought in as CEO to turn the company back to profitability. His strategy was to sell off all non-core assets and focus on the core businesses that built the company; grain handling and supplying farm inputs. 2004 would be a crucial year for Saskatchewan Wheat Pool. Key Words: publicly traded co-operative, business strategy, financial distress, company turn-around, financial restructuring L Corresponding author: Tel: + 306-966-8439 Email: [email protected] This case was prepared for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an agribusiness situation. The author(s) may have disguised names and other identifying information presented in the case in order to protect confidentiality. IAMA prohibits any form of reproduction, storage or transmittal without its written permission. To order copies or to request permission to reproduce, contact the IAMA Business Office. Interested instructors at an accredited university may request the teaching note by contacting the Business Office of IAMA. IAMA Agribusiness Case 7.3.B Presented at the 1st Annual IAMA Case Conference, Montreux, Switzerland, June 2004. -

238 Current Agriculture, Food & Resource Issues

N u m b e r 5 / 2 0 0 4 / p . 2 3 8 - 2 5 2 w w w . C A F R I . o r g Agriculture, Food C urrent & Resource Issues A Journal of the Canadian Agricultural Economics Society Member Commitment and the Market and Financial Performance of the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool K. A. Lang M.Sc. candidate, Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Saskatchewan M. E. Fulton Professor, Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Saskatchewan This paper was presented at the annual meeting of the Canadian Agricultural Economics Society (Halifax, June 2004) in a session entitled “What’s Happening in the Co-operative Sector?” Papers presented at CAES meetings are not subject to the journal’s standard refereeing process. The Issue Since 2001 several of the largest agricultural co-operatives in Western Canada and the United States have battled impending bankruptcy or ceased operations. In February 2001 Dairyworld Foods was bought out by Montreal dairy processor and cheese producer Saputo Inc. (Saputo; Toronto Stock Exchange). In November 2001, Agricore, formed through a 1998 merger of Alberta Wheat Pool Ltd. and Manitoba Pool Elevators, merged with United Grain Growers to form Agricore United (Agricore United). In the United States, AgWay and Farmland Industries filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in 2002 (Reuters, 2000), while the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool (hereinafter referred to as SWP or the Pool) underwent a massive debt restructuring in 2003 after four years of consecutive multi-million dollar net losses (SWP Annual Report, 2003). This decline in the market and financial performance of agricultural co-operatives has been associated with a decline in the commitment of the members to their co-operatives (Fulton, 1999; Fulton and Giannakas, 2001; Richards, Klein and Walburger, 1998; Burt 238 Current Agriculture, Food & Resource Issues K. -

PF Vol20 No1.Pdf (14.40Mb)

PRAIRIE FORUM Vol. 20, No.1 Spring 1995 CONTENTS ARTICLES U A Feudal Chain of Vassalage": Limited Identities in the Prairie West, 1870-1896 Theodore Binnema 1 Farming Technology and Crop Area on Early Prairie Farms Tony Ward 19 U An Imperfect Architecture of Power": Class and Local Government in Saskatchewan, 1908-1936 Rod Bantjes 37 A Populistin Municipal Politics: Cornelius Rink, 1909-1914 J. William Brennan 63 Prelude to Medicare: Institutional Change and Continuity in Saskatchewan, 1944-1962 Aleck Ostry 87 Is Soil Erosion a Problem on the Canadian Prairies? M.L. Lerohl and G.C. van Kooten 107 REVIEWS HOOD, George N., AgainsttheFlow: Rafferty-Alameda and thePolitics oftheEnvironment RICHARDSON, Mary, SHERMAN, Joan and GISMONDI, Michael, Winning Back theWords: Confronting Experts in an Environmental Public Hearing by Peter J. Smith 123 BUCKINGHAM, Donald E. and NORMAN, Ken, eds., Law, Agricultureand theFarm Crisis by Michael E. Gertler 128 SPRY, Irene M. and MCCARDLE, Bennett, TheRecords ofthe Department oftheInterior andResearch Concerning Canada's Western Frontier ofSettlement by Sarah Carter 131 TAYLOR,Jeffrey, Fashioning Farmers: Ideology, Agricultural Knowledge andtheManitoba Farm Movement, 1890-1925 byR. BruceShepard 133 GODFREY, Donald G. and CARD, Brigham Y.,TheDiaries of Charles Ora Card: TheCanadian Years 1886-1903 by John C. Lehr 134 NORTON, Wayne, Help Us toaBetterLand: Crofter Colonies in thePrairie West by J.R. Jowsey 136 CAVANAUGH, Catherine A. and WARNE, Randi R., eds., Standing onNew Ground: Women in Alberta by Sheilah L. Martin 138 CARENS, Joseph, Democracy andPossessive Individualism: TheIntellectual Legacy ofC.B.Macpherson by Brian Caterino 141 LETTERTO THE BOOK REVIEW EDITOR by Frits Pannekoek 146 CONTRIBUTORS 148 ---------------- PRAIRIE FORUM: Journal of the Canadian Plains Research Center ChiefEditor: Alvin Finkel, History, Athabasca Editorial Board: I. -

Journal of Cooperatives

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Journal of Cooperatives Volume 23 2009 Page 1-19 The Restructuring of the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool: Overconfidence and Agency Murray E. Fulton∗ Kathy A. Larsony ∗University of Saskatchewan, [email protected] yKnowledge Impact in Society, University of Saskatchewan, [email protected] The Restructuring of the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool: Overconfidence and Agency Murray E. Fulton and Kathy A. Larson This paper examines how agency problems combined with overconÞdence and hubris by coop management lead to financial failure in the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool. As a consequence of both of these problems, the Pool made poor investment decisions and ended up in severe financial difficulties. These problems were exac- erbated by three additional factors: (1) ownership and control were separated via an A-B share structure, leading to a situation where neither farmer members nor investors had an incentive to monitor management activities; (2) the sheer volume of investment activity undertaken made it virtually impossible for the board to stay on top of what was happening; and (3) as a result of the change financial structure, senior management had available a large amount of debt capital that it could spend. Introduction On 30 August 2007, the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool (SWP or Pool) officially be- came known as Viterra, thereby formally severing all links to its cooperative roots. The real loss of its cooperative structure, however, occurred