From Corn Laws to Wheat Board

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The U.F.A. Who Is Interested in the States Power Trust

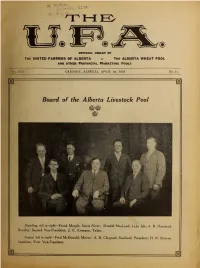

M. WcRae, ... pederal, Alta. OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE UNITED FARMERS OF ALBERTA THE ALBERTA WHEAT POOL AND OTHER PROVINCIAL MARKETING POOLS Vol. VIII. CALGARY, ALBERTA, APRIL 1st, 1929 No. 11. m Board of the Alberta Livestock Pool Standing, left to r/gA/—Frank Marple. Spirit River; Donald MacLeod, Lake Isle; A. B. Haarstad, Bentley. Second Vice-President; J. E, Evenson, Taber. Seated, left to right—Fred McDonald. Mirror; A. B. Claypool, Swalwell. President; H. N. Stearns. Innisfree, First Vice-President. 2 rsw) THE U. F. A. April iBt, lyz^i Ct The Weed-Killing CULTIVATOR with the exclusive Features The Climax Cultivator leads the war on weeds that trob these Provinces of $60,000,000 every year. Put it to work for you! Get the extra profits it is ready to make for you—clean grain, more grain, more money. The Climax has special featxires found in no Sold in Western Canada by other cultivator. Hundreds of owners acclaim it Cockshutt Plow Co., as a durable, dependable modem machine. Limited The Climax is made to suit every type of farm Winnipeg, Regina, and any kind of power. great variety of equip- Saskatoon, Calgary, A Edmonton ment for horses or tractors. Special Features of the Climax Manufactured by The Patented Depth Regulator saves The Frost & Wood Co., Limited pow«r and horse fag. The Power Lift saves time. Points working independ- Smiths Falls, Oat. ently do better work. Heavy Duty Drag Bars equipped with powerful coils prings prevent breakage. Rigid Angle Steel Frame. Variety of points from 2" to 14". llVi" points are standard eqvdpment. -

Gladstone and the Bank of England: a Study in Mid-Victorian Finance, 1833-1866

GLADSTONE AND THE BANK OF ENGLAND: A STUDY IN MID-VICTORIAN FINANCE, 1833-1866 Patricia Caernarv en-Smith, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Denis Paz, Major Professor Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Laura Stern, Committee Member Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Caernarven-Smith, Patricia. Gladstone and the Bank of England: A Study in Mid- Victorian Finance, 1833-1866. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 378 pp., 11 tables, bibliography, 275 titles. The topic of this thesis is the confrontations between William Gladstone and the Bank of England. These confrontations have remained a mystery to authors who noted them, but have generally been ignored by others. This thesis demonstrates that Gladstone’s measures taken against the Bank were reasonable, intelligent, and important for the development of nineteenth-century British government finance. To accomplish this task, this thesis refutes the opinions of three twentieth-century authors who have claimed that many of Gladstone’s measures, as well as his reading, were irrational, ridiculous, and impolitic. My primary sources include the Gladstone Diaries, with special attention to a little-used source, Volume 14, the indexes to the Diaries. The day-to-day Diaries and the indexes show how much Gladstone read about financial matters, and suggest that his actions were based to a large extent upon his reading. In addition, I have used Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates and nineteenth-century periodicals and books on banking and finance to understand the political and economic debates of the time. -

“Everybody Called Her Frank” : The

JOURNAL OF NEW BRUNSWICK STUDIES Issue 2 (2011) “Everybody Called Her Frank”1: The Odyssey of an Early Woman Lawyer in New Brunswick Barry Cahill Abstract In February 1934 Frances Fish was called to the bar of New Brunswick and spent the next forty years practising law in her home town of Newcastle (now City of Miramichi) NB. In 1918 she had been both the first woman to graduate LLB from Dalhousie University and the first woman to be called to the bar of Nova Scotia. Though she initially intended to remain in Halifax, she instead left Nova Scotia almost immediately, abandoning the practice of law altogether. She spent the next fifteen years working as a paralegal in Ottawa and Montreal before returning to New Brunswick and resuming the practice of law. This article is a study of Fish’s career in New Brunswick, framed within the experience of the first women lawyers in Canada, of whom she was the seventh.2 Résumé En février 1934, Frances Fish a été reçue au Barreau du Nouveau-Brunswick. Pendant les quarante années qui ont suivi, elle a pratiqué le droit dans sa ville natale, Newcastle (qui fait maintenant partie de la ville de Miramichi), au Nouveau-Brunswick. En 1918, elle a été la première femme à obtenir un baccalauréat en droit de la Dalhousie University et la première femme reçue au Barreau de la Nouvelle-Écosse. Bien qu’elle avait, au début, l'intention de rester à Halifax, elle a quitté la Nouvelle- Écosse presque immédiatement après ses études, abandonnant complètement la pratique du droit. -

Government Policy During the British Railway Mania and the 1847 Commercial Crisis

Government Policy during the British Railway Mania and the 1847 Commercial Crisis Campbell, G. (2014). Government Policy during the British Railway Mania and the 1847 Commercial Crisis. In N. Dimsdale, & A. Hotson (Eds.), British Financial Crises Since 1825 (pp. 58-75). Oxford University Press. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/british-financial-crises-since-1825-9780199688661?cc=gb&lang=en& Published in: British Financial Crises Since 1825 Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2014 OUP. This material was originally published in British Financial Crises since 1825 Edited by Nicholas Dimsdale and Anthony Hotson, and has been reproduced by permission of Oxford University Press. For permission to reuse this material, please visit http://global.oup.com/academic/rights. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 Government Policy during the British Railway Mania and 1847 Commercial Crisis Gareth Campbell, Queen’s University Management School, Queen's University Belfast, Belfast, BT7 1NN ([email protected]) *An earlier version of this paper was presented to Oxford University’s Monetary History Group. -

Corn Exchange 1891-1892

Berwick Advertiser 1891 Berwick Advertiser 1891 January 23, p. 2, column 5. BERWICK CHORAL UNION. MARITANA. Last night the members of Berwick Choral Union gave their 22nd annual concert in the Corn Exchange, which was filled by a numerous and appreciative audience. The work selected for performance this year was Vincent Wallace’s charming opera “Maritana,” which shares with “Lurline” a large measure of popular favour. The chief features of “Maritana” are its florid orchestration and its fine melodies. The dramatis personae of the opera are Maritana, a handsome gitana, soprano; Lazarillo, mezzo-soprano; Don Caesar de Bazan, tenor; Don Jose de Santarem, baritone; Captain of the Guard, baritone; the King, bass; the Alcade, bass; chorus and soldiers, gipsies and populace. The argument is as follows: Maritana, whilst singing to a crowd of people in a square in Madrid, attracts the admiration of the King of Spain. Don Jose, who is an unscrupulous courtier, observing this, determines to satisfy the King’s whim, and then to betray him to the Queen, with whom he is bold enough to be madly in love. Don Caesar de Bazan, who is an impetuous spendthrift, arrives upon the scene, and in order to protect Lazarillo, who is a poor boy, from arrest, challenges the Captain of the Guard, an action which by a recent edict of the King entails death by hanging. He is arrested and imprisoned, but by Don Jose’s influence his sentence is changed to the more soldier-like death of being shot, on condition that he marries a veiled lady; this he consents to do. -

Fast Policy Facts

Fast Policy Facts By Paul Dufour In collaboration with Rebecca Melville - - - As they appeared in Innovation This Week Published by RE$EARCH MONEY www.researchmoneyinc.com from January 2017 - January 2018 Table of Contents #1: January 11, 2017 The History of S&T Strategy in Canada ........................................................................................................................... 4 #2: January 18, 2017 Female Science Ministers .................................................................................................................................................... 5 #3: February 1, 2017 AG Science Reports ................................................................................................................................................................ 6 #4: February 8, 2017 The deadline approaches… ................................................................................................................................................. 7 #5: February 15, 2017 How about a couple of key moments in the history of Business-Education relations in Canada? .............. 8 #6: February 22, 2017 Our True North ........................................................................................................................................................................ 9 #7: March 8, 2017 Women in Science - The Long Road .............................................................................................................................. 11 #8: March 15, 2017 Reflecting on basic -

Exported to Death- the Failture of Agricultural Deregulation

+(,121/,1( Citation: 9 Minn. J. Global Trade 87 2000 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Wed Nov 11 17:37:03 2015 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=1944-0294 Exported to Death: The Failure of Agricultural Deregulation Robert Scott* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. FREEDOM TO FAIL: THE OMNIBUS 1996 FARM BILL ...................................... 89 II. INTERNATIONAL TRADE: THE SIREN'S SO N G ............................................ 92 III. TIME FOR A NEW FARM POLICY .............. 97 APPENDIX: THE CAUSES OF FALLING COMMODITY PRICES ........................... 99 In 1996, free market Republicans and budget-cutting Democrats offered farmers a deal: accept a cut in farm subsidies and, in return, the government would promote exports in new trade deals with Latin America and in the World Trade Organization (WTO) and would eliminate restrictions on planting decisions.1 In economic terms, farmers were asked to take on risks heretofore assumed by the government in exchange for deregulation and the promise of increased exports. 2 This sounded like a good deal to many farmers, especially since exports and prices had been rising for several years. Many farmers and agribusiness interests supported the bill, and it was in keeping with the position of many farmer representatives and most members of Congress from farm states who already supported the WTO, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and the extension of fast-track trade negotiating authority, usually in the name of supporting family farmers. -

Bowl Round 1 Bowl Round 1 First Quarter

NHBB Nationals Bowl 2015-2016 Bowl Round 1 Bowl Round 1 First Quarter (1) Elizabeth Tyler owned and operated a newspaper for this organization called The Searchlight, which ran articles written by Edward Young Clarke. The first national meeting of this group took place in 1867 at the Maxwell House Hotel in Nashville. This group was targeted in an 1871 Enforcement Act, and Nathan Bedford Forrest served as this group's first Grand Wizard. For ten points, name this cross-burning white supremacist group. ANSWER: Ku Klux Klan (or KKK) (2) One of this man's daughters helped build fortresses in Stafford, Warwick, and Chester, earning her the nickname \the Lady of the Mercians." After this father of Aethlflaed and Edward the Elder won at Chippenham and Edington, he converted Guthrum to Christianity, baptizing Guthrum as his spiritual son. The Bishop Asser chronicled the life of, for ten points, what king of Wessex who ruled from 871 to 899 who, like Canute, was styled \the Great?" ANSWER: Alfred the Great (3) One employee of this company, Gerhard Domagk, won a Nobel Prize but was arrested by the Nazis for contemplating accepting it. This company appointed Fritz ter Meer as its chair shortly after he finished his prison term for Nazi war crimes. Felix Hoffmann’s work with this company included an acetylation of morphine, creating a compound that this company trademarked as heroin. For ten points, name this German pharmaceutical company whose chemists synthesized acetylsalicylic acid, or aspirin. ANSWER: Bayer AG (4) Adi Dassler convinced this \Buckeye Bullet" to wear his Schuhfabriks, marking the first sponsorship of African-American male athletes. -

THE QUEEN's PRIVY COUNCIL for CANADA 61 Administrative Duties in the Various Departments of Government Became So Burden- Some Du

THE QUEEN'S PRIVY COUNCIL FOR CANADA 61 Administrative duties in the various departments of government became so burden some during World War II that Parliamentary Assistants were appointed to assist six Cabinet Ministers with their parliamentary duties. The practice was extended after the War and at May 31, 1955 there were 11 Parliamentary Assistants, as follows:—• To Prime Minister W. G. WEIR To Minister of Agriculture ROBERT MCCUBMN TO Minister of Fisheries J. WATSON MACNAUGHT TO Minister of Veterans Affairs C. E. BENNETT To Minister of National Defence J. A. BLANCHETTE To Minister of Transport L. LANGLOIS To Postmaster General T. A. M. KIRK To Minister of Finance W. M. BENIDICKSON To Minister of National Health and Welfare F. G. ROBERTSON To Minister of Defence Production JOHN H. DICKEY To Minister of Public Works M. BOURGET The Privy Council.—The Queen's Privy Council for Canada is composed of about seventy members who are sworn of the Council by the Governor General on the advice of the Prime Minister and who retain their membership for life. The Council consists chiefiy of present and former Ministers of the Crown. It does not meet as a functioning body and its constitutional responsibilities as adviser to the Crown in respect to Canada are performed exclusively by the Ministers who constitute the Cabinet of the day. 5.—Members of the Queen's Privy Council for Canada According to Seniority Therein as at May 31, 1955 NOTE.—In this list the prefix "The Rt. Hon." indicates membership in the United Kingdom Privy Council. Clerk of the Privy Council and Secretary to the Cabinet, R. -

Annexes Supplémentaires Et Photos

ANNEXES SUPPLÉMENTAIRES ETannexe PHOTOS 2 Tableaux : L’immigration arabe au Canada L’immigration arabe au Canada TABLEAU A Chiffres du recensement : les Arabes au Canada, par origine ethnique Années Arabes 1911 7 000 1921 8 282 1931 10 753 1941 11 857 1951 12 3011 1961 19 374 1971 26 665 1981 60 6852 1986 72 3153 1. La catégorie « syrien » de 1951 disparaît du recensement pour être remplacée par « syriens-libanais » en 1961 et 1971. Le recensé ne peut déclarer qu’une seule origine ethnique, correspondant aux antécédents paternels, est-il précisé. 2. En 1981, le recensé peut désormais indiquer plusieurs origines ethniques, mais ces résultats n’ont pas tous été publiés. Nous avons additionné les chiffres pour les origines : Arabes asiatiques 50 140 (Libanais : 27 320, Syrien : 3 455, Palestinien : 1005 et autres), Arabes nord-africains 10 545 (dont 9 140 Égyptiens). 3. Le tableau pour le recensement de 1986 propose une catégorie « origines arabes » dans laquelle il y a plusieurs sous catégories : Libanais (29 345), Syrien (3 045), Palestinien (1 070), Égyptien (11 580) et autres Arabes (27 275). 274 Se dire arabe au Canada Tableaux : L’immigration arabe au Canada 275 TABLEAU B Admissions en provenance du monde arabe au Canada TABLEAU C Statistiques Canada : origine ethnique des immigrants, par année 1946-1955 Années Syriens4 Année Syriens Arabes Libanais Égyptiens Total 1880-1890 50 1946 11 11 1890-1900 1 500 1947 25 1 26 1900-1910 5 500 1948 31 5 36 1910-1920 920 1949 72 25 97 1920-1930 1 100 1950 54 29 83 1930-1940 933 1951 229 52 281 1940-1950 192 1952 242 73 315 Années Total, pays arabes5 1953 227 18 245 1950-1960 5 000 1954 253 15 268 1960-1970 22 945 1955 118 56 208 17 399 1970-1980 30 635 Total 1 262 274 208 17 1 761 1980-1990 59 155 1990-2000 141 005 Source: Immigration statistics, Department Immigration and Citizenship, Canada. -

Master of Arts

The Federal Election of 1896 in Manitoba Revisited BY Roland C. Pajares A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba In Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of History University of Manitoba Winnipeg O R. C. Pajares, 2008. THE T]NTVERSITY OF MANTTOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDTES tr?t*rtr( COPYRIGHT PERMISSION The Federal Election of 1896 in Manitoba Revisited BY Roland C. Pajares A Thesis/Practicum submitted to the Facutty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree MASTER OF ARTS R. C. Pajares O 2008 Permission has been granted to the University of Manitoba Libraries to lend a copy of this thesis/practicum, to Library and Archives Canada (LAC) to lend a copy of this thesisþracticum, and to LAC's agent (UMlÆroQuest) to microfilm, sell copies and to p"nUsn an abstrict of this thesis/practicum. This reproduction or copy of this thesis has been made available by authority of the copyright owner solely for the purpose of private study and research, and may only be reproduced äna JopieO as permitted by copyright laws or with express written authorization from the copyright ownôr. ll ABSTRACT This thesis examines the federal election of 1896 in Manitoba. It is prompted by the question of why, during a brief period of six months, Manitoba voters retracted their support from the anti-Remedial and anti-coercionist Liberals in the Provincial election of January 1896 to elect the pro-Remedial and coercionist federal Conservatives in the federal election of 1896. -

L Strawhat Boom.Qxd

Contents Luton: Straw Hat Boom Town Luton: Straw Hat Boom Town The resources in this pack focus on Luton from the mid 1800s to the first decade of the 20th century. This period saw the rapid growth of Luton from a country market town to an urban industrial town. The process changed the size and appearance of the town and the lives of all those who lived and worked here. The aim of this pack is to provide a core of resources that will help pupils studying local history at KS2 and 3 form a picture of Luton at this time. The primary evidence included in this pack may photocopied for educational use. If you wish to reproduce any part of this park for any other purpose then you should first contact Luton Museum Service for permission. Please remember these sheets are for educational use only. Normal copyright protection applies. Contents 1: Teachers’ Notes Suggestions for activities using the resources Bibliography 2: The Town and its Buildings 19th Century Descriptions A collection of references to the town from a variety of sources. 1855 Map of Luton This map shows the growth of the town to the show west and the beginnings of High Town to the north-east. The railway is only a proposition at this point in time. Luton From St Anne’s Hill, 1860s This view looking north-west over the town shows the Midland Railway line to London. The embankment on the right of the picture still shows the chalky soil. In the foreground is Crawley Green Cemetery.