PF Vol20 No1.Pdf (14.40Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The U.F.A. Who Is Interested in the States Power Trust

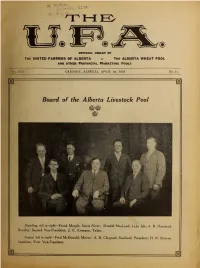

M. WcRae, ... pederal, Alta. OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE UNITED FARMERS OF ALBERTA THE ALBERTA WHEAT POOL AND OTHER PROVINCIAL MARKETING POOLS Vol. VIII. CALGARY, ALBERTA, APRIL 1st, 1929 No. 11. m Board of the Alberta Livestock Pool Standing, left to r/gA/—Frank Marple. Spirit River; Donald MacLeod, Lake Isle; A. B. Haarstad, Bentley. Second Vice-President; J. E, Evenson, Taber. Seated, left to right—Fred McDonald. Mirror; A. B. Claypool, Swalwell. President; H. N. Stearns. Innisfree, First Vice-President. 2 rsw) THE U. F. A. April iBt, lyz^i Ct The Weed-Killing CULTIVATOR with the exclusive Features The Climax Cultivator leads the war on weeds that trob these Provinces of $60,000,000 every year. Put it to work for you! Get the extra profits it is ready to make for you—clean grain, more grain, more money. The Climax has special featxires found in no Sold in Western Canada by other cultivator. Hundreds of owners acclaim it Cockshutt Plow Co., as a durable, dependable modem machine. Limited The Climax is made to suit every type of farm Winnipeg, Regina, and any kind of power. great variety of equip- Saskatoon, Calgary, A Edmonton ment for horses or tractors. Special Features of the Climax Manufactured by The Patented Depth Regulator saves The Frost & Wood Co., Limited pow«r and horse fag. The Power Lift saves time. Points working independ- Smiths Falls, Oat. ently do better work. Heavy Duty Drag Bars equipped with powerful coils prings prevent breakage. Rigid Angle Steel Frame. Variety of points from 2" to 14". llVi" points are standard eqvdpment. -

2018 Yellowknife Geoscience Forum Abstract and Summary Volume

2018 Abstract and Summary Volume Cover photograph Carcajou River, NWT; Viktor Terlaky, Senior Petroleum Geologist at the Northwest Territories Geological Survey The picture was taken following a rainstorm along Carcajou River, NWT, which resulted in a spectacular rainbow across the river valley. In the background are outcrops of the Late Devonian Imperial Formation, interpreted to be submarine turbidite deposits. The light bands are sandstone bodies intercalated with the darker shale intervals, representing periodic activity in sedimentation. Compiled by D. Irwin, S.D. Gervais, and V. Terlaky Recommended Citation: Irwin, D., Gervais, S.D., and Terlaky, V. (compilers), 2018. 46th Annual Yellowknife Geoscience Forum Abstracts; Northwest Territories Geological Survey, Yellowknife, NT. YKGSF Abstracts Volume 2018. - TECHNICAL PROGRAM - 2018 YELLOWKNIFE GEOSCIENCE FORUM ABSTRACTS AND SUMMARIES I Contents ordered by first author (presenting author in bold) Abstracts – Oral Presentations IBAS – to Regulate or Not: What is the Rest of Canada Doing? Abouchar, J. .......................................................................................................................... 1 Seabridge Discovers New Gold Zones at Courageous Lake Adam, M.A. ........................................................................................................................... 1 Gold Mineralisation at the Fat Deposit, Courageous Lake, Northwest Territories Adam, M.A. .......................................................................................................................... -

The Blood Tribe in the Southern Alberta Economy, 1884-1939

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Regular, W. Keith Book — Published Version Neighbours and networks: The blood tribe in the Southern Alberta economy, 1884-1939 Provided in Cooperation with: University of Calgary Press Suggested Citation: Regular, W. Keith (2009) : Neighbours and networks: The blood tribe in the Southern Alberta economy, 1884-1939, ISBN 978-1-55238-655-2, University of Calgary Press, Calgary, http://hdl.handle.net/1880/48927 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/182296 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ www.econstor.eu University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com NEIGHBOURS AND NETWORKS: THE BLOOD TRIBE IN THE SOUTHERN ALBERTA ECONOMY, 1884–1939 by W. -

December 2018

NWTTA NEWS Volume 20 • Issue 2 executive leadership & DECEMBER 2018 Planning Meetings 2018-2019 On October 25-27, 2018, Central Executive, Regional Regional Presidents Back Row (left to right): Patricia Oliver Presidents and Central office staff participated in our annual (YCS), Val Gendron (Dehcho), Éienne Brière (CSFTNO), Robin executive leadership & Planning meetings. Dhanoa (South Slave), JP Bernard (Sahtu), Stephen Offredi (YK1), Wendy Tulk (Tlicho) During the meetings the group met with staff from the Department of education, Culture & employment to discuss Central Executive Front Row (left to right): Gwen Young early Years education, the new “our language” curriculum (Member-at-Large), Todd Sturgeon (Secretary-Treasurer/ and teacher certification issues, reviewed NWTTA member Fort Smith Regional President), Fraser Oliver (President), Issues, Concerns and Celebrations survey results from June Marnie Villeneuve (Vice-President), Matthew Miller (Regional 2018 to provide direction on how we’re doing and what Presidents Representative/Beaufort-Delta Regional President) 2018-2019 priorities need to be. NWTTA NEWS • DECEMBER 2018 1 INsIDe: Yellowknife to Who executive leadership & Baton Rouge, Louisiana Are We? Planning Meetings 2018-2019 1 Fraser Oliver, President In october 2018 NWTTA Yellowknife to Baton Rouge, members completed a short Louisiana 2 The NWTTA held its regional orientations this demographic survey to school Profile september and in early october in all regional discover who we are. Who N.J. macpherson school 4 centers across the NWT. Photos from these Are We results are spread Northern Light regional orientations are featured throughout throughout this newsletter. Amanda Delaurier 6 this issue of the newsletter. Regional orientations Response rate for the survey Aboriginal sports Circle allow regional executives and school lRos to was about 23%, spread out NWTTA Award 2018 7 come together to deliberate on many topics by the below percentages by Northern Light relative to NWTTA members. -

Grain Elevators in Canada, As at August 1, 1998

Grain Elevators Silos à grains du in Canada Canada Crop year Campagne agricole 1998 - 1999 1998 - 1999 As at August 1, 1998 Au 1er août 1998 www.grainscanada.gc.ca © Canadian Grain Commission © Commission canadienne des grains TABLE OF CONTENTS Table 1 - Summary - All Elevators, By Province, Rail And Class Of Licence Table 2 - List Of Companies And Individuals Licensed Table 3 - Licensed Terminal Elevators Table 4 - Licensed Transfer Elevators Table 5 - Licensed Process Elevators Table 6 - Licensed Primary Elevator Storage Capacity, By Firms Table 7 - Licensed Grain Dealers Table 8 - Summary Of "Operating Units", By Province And Company Table 9 - Summary, Country Shipping Points And Licensed Primary Elevators Table 10 - Off-Line Elevators Situated In The Western Division Table 11 - All Elevators, By Stations - Manitoba - Saskatchewan - Alberta - British Columbia - Ontario - Quebec - Nova Scotia Appendix - Historical Record - All Elevators © Canadian Grain Commission © Commission canadienne des grains TABLE DES MATIÈRES Tableau 1 - Résumé - Tous les silos, par province, voie ferrée et catégorie de licence Tableau 2 - Liste des compagnies et des particuliers agréés Tableau 3 - Silos terminaux agréés Tableau 4 - Silos de transbordement agréés Tableau 5 - Silos de transformation agréés Tableau 6 - Capacité d'entreposage des silos primaires agréés, par compagnie Tableau 7 - Négociants en grains titulaires d'une licence Tableau 8 - Résumé des «Unités d'exploitation», par province et compagnie Tableau 9 - Résumé, Points d'expédition régionaux -

Métis Scrip in Alberta Rupertsland Centre for Métis Research in Collaboration with the Métis Nation of Alberta

Métis Archival ∞oject MÉTIS SCRIP IN ALBERTA RUPERTSLAND CENTRE FOR MÉTIS RESEARCH IN COLLABORATION WITH THE MÉTIS NATION OF ALBERTA Half-breed Scrip Comm si The research for this booklet was carried out by the Rupertsland Centre for Métis Research (RCMR), housed within the Faculty of Native Studies, University of Alberta, under the supervision of Dr. Nathalie Kermoal, Associate Dean Academic, Director of RCMR and relies upon the previous research completed by Dr. Frank Tough and the Métis Archival Project (MAP) Laboratory. Tough advised, edited and assisted with the compilation of this booklet. The documents for this project have been provided through the MAP Laboratory, under the supervision of Tough, who digitized and catalogued many of the Métis scrip records housed at Library and Archives Canada. This booklet has been prepared for the Métis Nation of Alberta Annual General Assembly (August 10- 12, 2018) by Nathalie Kermoal, Frank Tough, Jenn Rossiter and Leah Hrycun, with an overview of the New Framework Agreement by Jason Madden and Zachary Davis. Thank you to Lorne Gladue, Frank Tough and Zachary Davis for their feedback on this document. The views and ideas expressed herein are solely those of the creators and do not necessarily represent the views of the Métis Nation of Alberta, RCMR, the Faculty of Native Studies, MAP Laboratory, the University of Alberta, or Pape Salter Teillet LLP. Interior of Scrip commission tent at Lesser Slave Lake, Alberta. 1899. Source: Glenbow Archives (NA-949-22). Front Cover: Metis meeting with Scrip Commission at Fort Dunvegan, Alberta. 1899. Source: Glenbow Archives (NA-949-28). -

Fall 2007 (PDF)

Saskatchewan flax G r o w e r Chair’s Report What a difference a year can make!! The Commission is sponsoring a straw The Canadian dollar is at par! Agriculture has gone management workshop on February 12 and 13, from where governments are not interested in basic Allen Kuhlmann 2008. Green people are aiming their sights on fire Chair, research (because we only grow commodities which – learn how not to burn straw and maybe make Saskatchewan Flax Development are in surplus) to where prices have exploded on a buck. As a result of the environmental concerns Commission many of those same commodities. Nations are block- the Commission will continue working with the Ag ing exports to protect domestic food supplies and Environmental Group to modify farm practices. importing no matter what the cost. WOW! I wonder if Read more regarding this in the following pages. those in Ottawa and elsewhere that fund agronomic After a very long wait and much pain to dial Our Mission research have noticed? up internet users, we have a brand new website: “To lead, promote, How high would those prices be if the Canadian www.saskflax.com. Check it out if you haven’t dollar was .65 or .80? Interesting times for sure! I already. and enhance the hope this optimism and good times survive longer Areas where I have traveled suggest flax production, than higher input costs! yields didn’t suffer as much as some other crops. value-added Now to more mundane but also important I hope this was the case on your farm. -

Prairie Forum

(;ANADJAN PLAINS RESEARCH CENTER, University of Regina, Regina, Sask., Canada S4~ OA2 PRAIRIE FORUM Vol.6, No.2 Fall,1981 CONTENTS ARTICLES Autonomy and Alienation in Alberta: Premier A. C. Rutherford D. R. Babcock 117 Instilling British Values in the Prairie Provinces David Smith 129 Charlotte Whitton Meets "The Last Best West": The Politics of Child Welfare in Alberta, 1929-49 143 Patricia T. Rooke and R. L. Schnell The Trade in Livestock between the Red River Settlement and the American Frontier, 1812-1870 b Barry Kaye 163 Estimates of Farm Making Costs in Saskatchewan, 1882 ... 1914 Lyle Dick 183 RESEARCH NOTES Colour Preferences and Building Decoration among Ukrainians in Western Canada John C. Lehr 203 "The Muppets" among the Cree of Manitoba Gary Granzberg and Christopher Hanks 207 BOOK REVIEWS (see overleaf) 211 COPYRIGHT1981 ISSN0317-6282 CANADIAN PLAINS RESEARCH CENTER BOOK REVIEWS ARCHER, JOHN H., Saskatchewan, A History by Lewis G. Thomas 211 PALMER,HOWARD and JOHN SMITH (eds), The New Provinces: Alberta and Saskatchewan 1905-1980 by John Herd Thompson 213 WOODCOCK, GEORGE, The Meeting of Time and Space: Region- alism in Canadian Literature by William Howard 216 PARR, JOAN (editor), Manitoba Stories by David Carpenter 218 VAN KIRK, SYLVIA, "Many Tender Ties" Women in Fur-Trade Society in Western Canada by Philip Goldring 223 BROWN, C. et aI., Rain of Death: Acid Rain in Western Canada by D. M: Secoy 225 HALL, D. J., Clifford Sifton: Volume I. The Young Napoleon, 1861-1900 by Gerald J. Stortz 227 HYLTON, JOHN, Reintegrating the Offender by James J. Teevan 229 ROGGE, JOHN (editor), The Prairies and the Plains: Prospects for the 80s by Alec H. -

Imperial Plots

IMPERIAL PLOTS IMPERIAL PLOTS Women, Land, and the Spadework of British Colonialism on the Canadian Prairies SARAH CARTER UMP-IMPERIAL-LAYOUT-REVISEDJAN2018-v3.indd 3 2018-03-09 12:19 PM Imperial Plots: Women, Land, and the Spadework of British Colonialism on the Canadian Prairies © Sarah Carter 2016 Reprinted with corrections 2018 21 20 19 18 2 3 4 5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database and retrieval system in Canada, without the prior written permission of the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or any other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, www.accesscopyright.ca, 1-800-893-5777. University of Manitoba Press Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Treaty 1 Territory uofmpress.ca Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada isbn 978-0-88755-818-4 (paper) isbn 978-0-88755-532-9 (pdf) isbn 978-0-88755-530-5 (epub) Cover design: Frank Reimer Interior design: Jess Koroscil Cover image: Sarah Minnie (Waddy) Gardner on her horse “Fly,” Mount Sentinel Ranch, Alberta, 1915. Museum of the Highwood, MH995.002.008. Printed in Canada This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publica- tions Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. The University of Manitoba Press acknowledges the financial support for its publication program provided by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Department of Sport, Culture, and Heritage, the Manitoba Arts Council, and the Manitoba Book Publishing Tax Credit. -

Mcphillips' Alphabetical and Business Directory of the District Of

w^ ^ ^f ^^. ^. «> ^^ IMAGE EVALUATION TEST TARGET (MT-3) ,'1 so """"• mH 1^ litt 12.2 Sf 144 "" u I4£ 12.0 I.I IE 1.25 U 11.6 I % Photographic 7 33 WIST MAIN STRUT WIUTM.N.Y. MIM Sciences (71*)I73-4S03 Corporation '4^^ / %^ CIHM/ICMH CIHM/ICIVIH Microfiche Collection de Series. microfiches. Canadian Instituta for Historical l\Aicroraproductions / Institut Canadian da microraproductions historiquaa Technical and Bibliographic Notes/Notes techniques et bibliographiquee The toti Tea institute has attempted to obtain the best L'Institut a microfilm^ le meilleur exemplaire original copy available for filming. Features of this qu'il lui a St6 possible de se procurer. Les details copy which may be bibliographically unique, de cet exemplaire qui sont peut-Atre uniques du which may alter any of the images in the point de vue bibliographique, qui peuvent modifier The reproduction, or which may significantly change une image reproduite, ou qui peuvent exiger une posi the usual method of filming, are checked below. modification dans la methods normale de filmage oft» indiqufo ci-dessous. sont film Coloured covers/ |~n Coloured pages/ D Couverture de couleur Pages de couleur Or;g begl the Covers damaged/ I Pages damaged/ I I Couverture endommagte I— Pages endommag^es sion othe first Covers restored and/or laminated/ I Pages restored and/orand/oi laminated/ I— sion, Couverture restaur6e et/ou peliicul^e Pages restauries et/ou pellicultes or ill Cover title missing/ fy] Pages discoloured, stained or foxed/foxe( I I Le titre de couverture manque Pages dteolortes, tachettes ou piqutes Coloured maps/ Pages detached/ The I I Cartes gtegraohiques en couleur Pages ditachtes shall TINl whic Coloured ink (i.e. -

Corporate Greed Does Not Spare Cooperatives: Chronicle of the Disappearance of the Largest Agri-Food Cooperative in Canada by Assoumou-Ndong, Franklin

Corporate greed does not spare cooperatives: chronicle of the disappearance of the largest agri-food cooperative in Canada by Assoumou-Ndong, Franklin Global and diverse cooperative enterprise, Saskatchewan Wheat Pool (SWP), now known as Viterra Inc., has been ranked for years among the 50 largest companies in Canada, including the first in the handling and distribution of grain and also the largest agri-food cooperative in the country. It was the pride of an entire province. Supporters of the cooperative model present it as an alternative model for excellence in business, based on a human vision of enterprises focused on community empowerment and democracy. In the late 1800s, after years of battle and frustration against government policies of capitalism’s free market in agriculture, farmers in western Canada understood the need to regroup, precisely in cooperatives, to counter the harmful effects of free market and speculative fluctuations in grain prices. Cooperation appeared then as an alternative to economic and social exploitation of the people, especially in rural communities. Cooperatives were becoming tools for social change to support members (or community) and the redistribution of economic power. In June 1924, nearly 46 000 farmers, producing mainly wheat, officially signed a new contract that united them under the banner of Saskatchewan Cooperative Wheat Producers Ltd . (incorporated in 1923); the cooperative was subsequently renamed (in 1953) the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool . The cooperative has gone through many difficult times, such as the Great Depression of the 1930s, and has had good years with instances of record operating surplus (profits) and healthy membership numbers of farmer members (Assoumou-Ndong, 2001a; Lang, 2007). -

In Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba, Canada

Landscape-Level Vegetation Dynamics in Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba, Canada by Richard Caners thesis presented to the University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the Faculty of Graduate Studies Departrnent of Botany University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3T 2N2 @ Richard Caners 2001 NationalLibrarY Bibliothèque nationale l*l du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 3!15, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KlA 0|,¡4 OttawaON KlA0N4 Canada Canada Yùt frle Voús rólèmæ Oufrle ì'loÚetélétw The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loatr, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sr¡r format électonique. The author reteins o\ilnership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyn&t in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sâns son permission. autorisation. 0-612-76901-1 Canad'ä THE T]NTYERSITY OF MANITOBA F'ACULTY OF GRADUATB STIIDIES ¡trr**tr COPYRIGHT