Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0304 Hoopm Gd P149-180.Pmd

A Look at Cal The University of California CAMPUS ADMINISTRATION In his eight years at Cal, Mitchell’s strategic focus has been on ROBERT M. BERDAHL enhancing Cal’s administrative organizational culture to better serve the campus community. He has emphasized strengthening leadership across CHANCELLOR all departments, improving business processes, and optimizing the use of technology through campus-wide implementations such as the Berkeley Dr. Robert M. Berdahl took office in July of Financial System and the Human Resources Management System. 1997 as UC Berkeley’s eighth chancellor with In addition to his administrative responsibilities, Mitchell is a licensed a promise to renew the University’s foundations psychologist and an affiliated professor in the Department of African of excellence. He has established a comprehensive American Studies. He has continued to teach one course each year that master-plan that is guiding work on major seismic is cross-listed in psychology. and infrastructure upgrades to campus buildings, and is addressing the Mitchell joined the administration at Cal in April 1995 after 17 years need for space suitable for modern research and teaching. He has worked of service at UC Irvine where he spent 11 years as vice chancellor-student to successfully rebuild the library collection and has also been active in affairs and campus life and, before that, several years as associate dean supporting two new collaborations. for student and curricular affairs in the UCI College of Medicine. He held A career-long advocate of enhancing and humanizing undergraduate a faculty appointment as associate clinical professor of psychiatry and learning, Berdahl has expanded the highly popular Freshman Seminars in human behavior. -

Dalida Arakelian1, Sean Dreyer2 Event

MindFul Music: The Power of Live Music Dalida Arakelian1, Sean Dreyer2 1. David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA; Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 2. David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA Background Methods & Research Timeline UCLA students, staff, and faculty are in competitive, rigorous setting and at risk for high day-to-day stress levels and long- Event Process Execution term burnout. Music has been well established as a Map of Pop Up therapeutic intervention for various mental health issues, Location Future including stress. To promote a healthier environment at UCLA, Partnership Music Event Spring 2015: State: MindFul Music was founded as a series of pop up music publish events at various campus locations. Pop Up Music Winter 2015: Events: 6 research On Site Recruit Locations article to Survey Student Fall 2014: Monthly hotspots What is MindFul Music? Launch Single Expansion: 3 across campus encourage Execution Musicians Fall 2013: A Hotspot: 4 hotspots; IRB expansion An interdisciplinary approach designed to uncover and share the spontaneous professional Approval to to other positive health benefits of live music and to scientifically quantify conversation health execute universities these results. with Jane schools research Coordinate Semel & Dr. Pop Up Event Whybrow Objectives Scheduling & Management Publicity Results & Future Goals Improve brain- Promote social Preliminary Results Future Goals mind health: connections: lower stress levels, among -

WASHINGTON STATE VOLLEYBALL RELEASE COUGARS (12-12, 4-10 Pac-12) THIS WEEK

WASHINGTON STATE VOLLEYBALL RELEASE COUGARS (12-12, 4-10 Pac-12) THIS WEEK: @ No. 4 USC (18-4, 13-2 Pac-12) Friday, Nov. 4, Galen Center 7 p.m. @ No. 1 UCLA (20-3, 13-2) Sunday, Nov. 6, John Wooden Center, 1 p.m. Linda Chalich • Athletic Communications Asst. Dir. (Volleyball Contact) • W-509-335-0268 • C-509-432-3263 • [email protected] 2011 WSU VOLLEYBALL SCHEDULE WSU VOLLEYBALL GOES TO LOS ANGELES TO MEET PAC-12 TOP TEAMS & RESULTS (All Times Pacific) The Washington State University volleyball team (12-12 overall, 4-10 Pac-12) travels to Los Angeles to take on a pair of highly ranked teams that are fight- AUGUST ing for the initial Pac-12 championship title...Cougars play at No. 4 USC (18- Seattle University Invite, Seattle 4, 13-2) Friday, Nov. 4 in a 7 p.m. match at the Galen Center...WSU will have a 26 W, 3-1 Santa Clara day off before meeting No. 1 UCLA (20-3, 13-2) for a Sunday, Nov. 6 match in 27 L, 2-3 Eastern Washington the John Wooden Center at 1 p.m...Bruins are playing in the Wooden Center W, 3-2 @ Seattle University due to renovations in Pauley Pavilion...Cougars opened conference play this season against the Bruins and Women of Troy...both contests will be live on SEPTEMBER radio on KQQQ 1150 AM and on the Cougars All-Access subscription inter- Portland Nike Invitational, Portland net connection. 2 W, 3-0 vs. Nevada W, 3-2 @ Portland COUGAR COACHING STAFF 3 W, 3-1 Butler First year Head Coach Jen Stinson Greeny (12-12 at WSU, 124-36 in 5-year ca- L, 0-3 Texas A&M reer) is no stranger to Washington State volleyball...an outstanding student Nike Cougar Challenge, Pullman and athlete at WSU, Greeny was an All-Pac-10 player and member of three 9 W, 3-0 Manhattan College NCAA teams including the 1996 Elite Eight team...also an assistant coach W, 3-2 San Francisco for three more NCAA appearances including the 2002 Elite Eight team...had 10 W, 3-1 Sam Houston State highly successful NAIA coaching career at Lewis-Clark State College (LCSC) 16 L, 0-3 *No. -

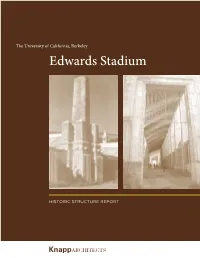

Edwards Stadium

The University of California, Berkeley Edwards Stadium Historic structure report The University of California, Berkeley Edwards Stadium HISTORIC STRUCTURE REPORT Contents IntroductIon .................................................................................07 descrIptIon & condItIons assessment ...................65 purpose and scope ................................................................. 10 site and Landscape .................................................................66 subject of this study ............................................................. 10 Landscape Around the stadium .......................................67 Methodology .................................................................................11 Landscape inside the stadium ..........................................75 exterior Description ................................................................78 HIstorIcal context ..................................................................17 interior Description ..................................................................87 early History of Berkeley: 1820-1859 ...............................18 Materials and Features ...........................................................92 college of california: 1860-1868 ........................................19 condition ......................................................................................99 early physical Development of the Berkeley campus ..................................................................... 20 analysIs of HIstorIcal -

Fwd: CF 17-0156 Japanese Garden HCM

4/3/2017 City of Los Angeles Mail - Fwd: CF 17-0156 Japanese Garden HCM * LA Edwin Grover <[email protected]> GE£CS I© Fwd: CF 17-0156 Japanese Garden HCM Sharon Dickinson <[email protected]> Mon, Apr 3, 2017 at 9:16 AM To: Edwin Grover <[email protected]> Piease upload and make copies for Comittee members. Thanks. --------- Forwarded message -.......... - From: "Marian A Dodge" <[email protected]> Date: Apr 2, 2017 7:51 PM Subject: CF 17-0156 Japanese Garden HCM To: <[email protected]>, <shawn.kuk@lacity,org> Cc: "Adrian Fine" <[email protected]>, "Lambert Giessinger" <[email protected]> Dear Sharon, Piease distribute this letter supporting the designation of the Hannah Carter Japanese Garden as a Historic-Cultural i Monument to the members of the PLUM Committee. Thank you. Best regards, Marian Dodge, Chairman Federation of Hillside and Canyon Associations, Inc. www.hillsidefederation.org 2 attachments The Fed. logo-3in. email.pdf ^ 72K fq CF 17-0156 Japanese Garden HCM.pdf ^ 102K https ://mail.google.com/mail/?ui=2&ik=097dfaf34f&view=pt&search=inbox&msg=15b349aaf04bdd35&siml=15b349aa104bdd35 1/1 P.O. Box 27404 Los Angeles, CA 90027 www.hillsidefederation.org ■ 11 iill'iMk. PRESIDENT Charley Mims THE FEDERATION CHAIRMAN OF HILLSIDE AND CANYON ASSOCIATIONS, INC. Marian Dodge VICE PRESIDENTS Mark Stratton John Given PLUM Committee SECRETARIES City Hall Carol Stdlow 200 N. Spring Street John Given Los Angeles, CA 90012 TREASURER Don Andres April 2, 2017 Beachwood Canyon Neighborhood Bel-Air Associelion Sei-Air Hills Assn. Bel Air Knolls Properly Owners Bel Air Skycrest Property Owners Benedict Canyon Association Brentwood Hilfe Homeowners Brentwood Residents Goaiition Re: Council File 17-0156 Cahuenga Pass Property Owners Ethel Guiberson/Hannah Carter Japanese Garden Canyon Back Alliance CASM-SFV Crests Neighborhood Assn. -

Welcome to Your Life As an EMBA Student!

Ready to Go | 2020 Welcome to Your Life as an EMBA Student! You are about to embark on an incredible journey, focused on a goal of dynamic education, career development and personal growth. As you now consider accepting our offer of admission, you have a lot of important changes to plan for: evaluating the current balance of your job responsibilities; managing your personal life commitments; and reacquainting yourself with being a student again. You will begin a program with rigorous coursework and team projects, surrounded by a remarkable number of extremely intelligent people. We hope you will acknowledge the significance of your decision and the impact it will have on your life. We expect you to be both excited and apprehensive about this decision and hope that you will use the information provided to learn how much your life as a USC Marshall EMBA student will expand not only your mind and career opportunities, but also your social circle and your spirit. In the pages that follow, you will learn more about the personal and social enrichment opportunities that the Marshall School of Business and USC have to offer. THE USC MARSHALL SCHOOL OF BUSINESS Established in 1920, the USC Marshall School of Business is the oldest accredited business school in Southern California. Marshall is a private research and academic institution committed to educating tomorrow’s global leaders. Ranked as one of the country’s top schools for accounting, finance, entrepreneurship and international business studies, Marshall also shares the rich history and vibrant community of the USC academic system. Situated in Los Angeles, California, the Marshall School provides ready access to industries defining the new business frontier: biotechnology, life sciences, media, entertainment, communications and healthcare. -

Commartslectures00connrich.Pdf

of University California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California University History Series Betty Connors THE COMMITTEE FOR ARTS AND LECTURES, 1945-1980: THE CONNORS YEARS With an Introduction by Ruth Felt Interviews Conducted by Marilynn Rowland in 1998 Copyright 2000 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Betty Connors dated January 28, 2001. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

OF the UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Editorial Board

OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Editorial Board Rex W Adams Carroll Brentano Ray Cohig Steven Finacom J.R.K. Kantor Germaine LaBerge Ann Lage Kaarin Michaelsen Roberta J. Park William Roberts Janet Ruyle Volume 1 • Number 2 • Fall 1998 ^hfuj: The Chronicle of the University of California is published semiannually with the goal of present ing work on the history of the University to a scholarly and interested public. While the Chronicle welcomes unsolicited submissions, their acceptance is at the discretion of the editorial board. For further information or a copy of the Chronicle’s style sheet, please address: Chronicle c/o Carroll Brentano Center for Studies in Higher Education University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-4650 E-mail [email protected] Subscriptions to the Chronicle are twenty-seven dollars per year for two issues. Single copies and back issues are fifteen dollars apiece (plus California state sales tax). Payment should be by check made to “UC Regents” and sent to the address above. The Chronicle of the University of California is published with the generous support of the Doreen B. Townsend Center for the Humanities, the Center for Studies in Higher Education, the Gradu ate Assembly, and The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, California. Copyright Chronicle of the University of California. ISSN 1097-6604 Graphic Design by Catherine Dinnean. Original cover design by Maria Wolf. Senior Women’s Pilgrimage on Campus, May 1925. University Archives. CHRONICLE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA cHn ^ iL Fall 1998 LADIES BLUE AND GOLD Edited by Janet Ruyle CORA, JANE, & PHOEBE: FIN-DE-SIECLE PHILANTHROPY 1 J.R.K. -

UCLA University Archives. Subject Files (Reference Collection)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8v1266j No online items University Archives. Subject Files (Reference Collection). 1881- Finding aid prepared by University Archives staff, 2012 September; finding aid revised by cbbrown, 2013 March; machine-readable finding aid created by Katharine Lawrie, 2013 June; additional EAD encoding revision by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] Online findinga aid last updated 30 March 2017. University Archives. Subject Files 746 1 (Reference Collection). 1881- Title: UCLA University Archives. Subject files (Reference Collection). Collection number: 746 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 40.0 linear ft. Date: 1881- Abstract: Record Series 746 contains information on academic programs, buildings, events, and organizations affiliated with: the Los Angeles State Normal School (LASNS), 1881-1919; the University of California, Southern Branch, 1919-1926; and the University of California, Los Angeles, 1927- . The contents of the Subject Files (Reference Collection) include: reports, statistical data, histories of academic departments, organization charts, pamphlets, and other miscellaneous items. Creator: UCLA University Archives. Conditions Governing Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance through our electronic paging system using the "Request items" button. Publication Rights Copyright of portions of this collection has been assigned to The Regents of the University of California. The UCLA University Archives can grant permission to publish for materials to which it holds the copyright. -

2019 USC WVB Quick Facts

DEPARTMENT OF INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS • HER 103 • LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90089-0601 • TELEPHONE: (213) 740-8480 • FAX: (213) 740-7584 SPORTS INFORMATION OFFICE • WOMEN’S VOLLEYBALL CONTACT: JEREMY WU • MOBILE: (213) 379-3977 • E-MAIL: [email protected] 2019 USC WOMEN’S VOLLEYBALL QUICK FACTS UNIVERSITY INFORMATION USC VOLLEYBALL HISTORY Location ................................................................................ Los Angeles, California First Season of Women’s Volleyball * ................................................................ 1976 Founded ............................................................................................................... 1880 First Volleyball Head Coach ..................................................... Chuck Erbe (1976-77) Enrollment ....................................................................................................... 43,000 All-Time Record ............................................................................ 1,054-367-4 (.740) Campus Size ............................................................................................... 150 Acres All-Time Conference Record .............................................................. 510-213 (.705) President ........................................................................................... Dr. Carol L. Folt All-Time Postseason Record ................................................................ 126-40 (.759) Athletic Director ..................................................................................... -

Understanding the Causes and Effects of Regional Orchestra Bankruptcies in the San Francisco Bay Area

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Breakdown on the Freeway Philharmonic: Understanding the Causes and EFFects oF Regional Orchestra Bankruptcies in the San Francisco Bay Area A dissertation submitted in partial satisFaction oF the requirements for the degree Doctor oF Philosophy in Music by Alicia Garden Mastromonaco Committee in charge: ProFessor Derek Katz, Chair ProFessor SteFanie Tcharos ProFessor Martha Sprigge December 2020 The dissertation oF Alicia Garden Mastromonaco is approved. _____________________________________________ Martha Sprigge _____________________________________________ SteFanie Tcharos _____________________________________________ Derek Katz, Committee Chair December 2020 Breakdown on the Freeway Philharmonic: Understanding the Causes and EFFects oF Regional Orchestra Bankruptcies in the San Francisco Bay Area Copyright © 2020 by Alicia Garden Mastromonaco iii DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to my Friends and colleagues in the Bay Area orchestral world, the Freeway Philharmonic musicians. I hope that this project might help us keep our beloved musical spaces for a long time to come. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I must first acknowledge my advisor Derek, without whose mentorship this project likely would not have existed. He encouraged me to write about small regional orchestras in the Bay Area and saw the kernel oF what this project would become even beFore I did. His consistent support and endless knowledge on closely related topics shaped nearly every page oF this dissertation. I am also grateFul to SteFanie Tcharos and Martha Sprigge, who have inspired me in their rigorous approach in writing, and who have shaped this dissertation in many ways. This project was borne out oF my own experiences as a musician in the Bay Area orchestral world over the last fourteen years. -

Media Outlets Media Information

Duis nibh ex exer si bla at acil iril etum zzril ex el in ver illaore MEDIA INFORMATION PRESS CREDENTIALS practice schedules. Arrangements to UCLA campus at the corner of Bellagio Media and photography credentials for attend practice must be made in advance and DeNeve Drive. Use above directions UCLA home games may be obtained by through the sports information offi ce. There to reach campus, but exit the 405 Freeway working press only by writing or calling Amy will be no availability on gamedays prior onto Sunset Boulevard. Travel east on Hughes at the UCLA Sports Information to competition. Post game interviews at Sunset to Bellagio Drive, which is just east of Offi ce, PO Box 24044, Los Angeles, CA UCLA’s Easton Stadium are conducted Veteran Ave. (approx. 1 mile from freeway) 90024, (310) 206-8123; email: asymons@ in the home bullpen following the team and before the Westwood Blvd. entrance to ucla.edu. All requests should be submitted meeting. Please contact Amy Hughes in the campus. Turn right onto Bellagio, then right at least 24 hours in advance. Press and sports information department to schedule onto DeNeve Drive to enter parking lot 11. photo credentials can be picked up at the all interviews. The entrance to Easton Stadium is on the entrance gate. northeast corner of Bellagio and DeNeve. TRAVEL INFORMATION Parking can be purchased at lot 11 on game PHOTOGRAPHY For security purposes, the UCLA Sports days, or at the parking kiosk located at the Television and photo credentials entitle Information Offi ce does not release to the Westwood Plaza entrance to campus.