Edwards Stadium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California Rebuilding Fund

Welcome to the Information Forum for California Local Governments on the California Rebuilding Fund A public-private partnership supporting our small businesses Hosted by the Haas School of With Presentations by: Business, UC Berkeley Sustainable and Impact Finance Initiative Professors Laura Tyson and Adair Morse 1 The motivation of this work is to support small businesses through trusted, local community lenders in partnership with public and private sector leaders • Small businesses desperately need rebuilding capital • PPP, EIDL, and local grant/subsidized loan programs have kept the lights on • Our goal: Provide working capital loan support for rebuilding • CDFIs are the cornerstone to reach those in need • Essence of the program is to provide capital, technical assistance and credit support to enable our local CDFIs to reach those most in need • Public-private partnership to leverage State + other government/ philanthropic dollars with private capital to reach as many small businesses as possible • $50M Guarantee Facility • $250-500M Blended Facility 2 The perspective and leadership of the State of California Scott Wu Isabel Guzman 3 The economic case for small business support programs Professor Adair Morse 4 Economics 101 - Evidence: Providing access to affordable credit leads to the wellbeing of small businesses and communities Small Business Economics: Community Economics: Evidence from the Canada Small Business When small businesses sell goods Financing Program run during the 2007-2009 and services, revenues and foot economic -

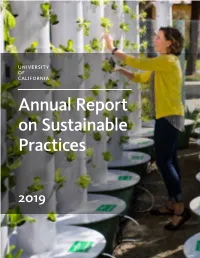

Annual Report on Sustainable Practices

SUSTAINABLE PRACTICES TABLE OF CONTENTS Annual Report on Sustainable Practices 2019 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 A SUSTAINABLE PRACTICES TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents A Message from the President ............................................ 1 The Campuses .................................................................. 24 UC Berkeley .................................................................................... 25 Summary: 2019 Progress Toward Policy Goals .................... 3 UC Davis ...........................................................................................29 UC Irvine ...........................................................................................33 UCLA ..................................................................................................35 2019 Awards ...................................................................... 4 UC Merced .......................................................................................41 UC Riverside ....................................................................................45 Timeline of Sustainability at UC .......................................... 5 UC San Diego ...................................................................................49 UC San Francisco ............................................................................53 UC Sustainable Practices Policies ........................................ 6 UC Santa Barbara .......................................................................... 57 Climate and Energy ..........................................................................7 -

0304 Hoopm Gd P149-180.Pmd

A Look at Cal The University of California CAMPUS ADMINISTRATION In his eight years at Cal, Mitchell’s strategic focus has been on ROBERT M. BERDAHL enhancing Cal’s administrative organizational culture to better serve the campus community. He has emphasized strengthening leadership across CHANCELLOR all departments, improving business processes, and optimizing the use of technology through campus-wide implementations such as the Berkeley Dr. Robert M. Berdahl took office in July of Financial System and the Human Resources Management System. 1997 as UC Berkeley’s eighth chancellor with In addition to his administrative responsibilities, Mitchell is a licensed a promise to renew the University’s foundations psychologist and an affiliated professor in the Department of African of excellence. He has established a comprehensive American Studies. He has continued to teach one course each year that master-plan that is guiding work on major seismic is cross-listed in psychology. and infrastructure upgrades to campus buildings, and is addressing the Mitchell joined the administration at Cal in April 1995 after 17 years need for space suitable for modern research and teaching. He has worked of service at UC Irvine where he spent 11 years as vice chancellor-student to successfully rebuild the library collection and has also been active in affairs and campus life and, before that, several years as associate dean supporting two new collaborations. for student and curricular affairs in the UCI College of Medicine. He held A career-long advocate of enhancing and humanizing undergraduate a faculty appointment as associate clinical professor of psychiatry and learning, Berdahl has expanded the highly popular Freshman Seminars in human behavior. -

MURR CENTER - 3Rd Floor Lounge Harvard University 65 North Harvard Street, Allston

MURR CENTER - 3rd Floor Lounge Harvard University 65 North Harvard Street, Allston MURR CENTER X X staIRS ELEVatOR X ACCESS X X T TREE X metered parking spots ARD S stairs ARV GATE 8 *Parking at metered spaces in the athletic facility is extremely TH H elevator access limited. Please see Parking section below for details. NOR From the West Take the Massachusetts Turnpike east to Exit 18 (Allston/Cambridge). After paying toll, bear left at fork towards Allston. Turn right at second set of lights onto North Harvard Street. Proceed approximately one mile. The Murr Center will be on your left. From the North Take I-93 south to Storrow Drive exit. Take Storrow Drive west for approximately five miles. Exit at Harvard Square/North Harvard Street. At top of exit, turn left onto North Harvard Street. You will see Blodgett Pool and then the Murr Center on your right. From the South Take I-95 north to I-93 north. Follow I-93 until Exit 20 (Massachusetts Turnpike). Take Mass. Pike west to Exit 20 (Allston/Cambridge). After paying toll, bear left at fork towards Allston. Turn right at second set of lights onto North Harvard Street. Proceed approximately one mile. The Murr Center will be on your left. Parking Limited parking is available within the athletic complex. Enter at Gate 8 on North Harvard Street and circle around behind the stadium to find metered spaces. Some parking is available on the street. You can also purchase a visitor’s parking pass to the Harvard Business School Lot which is located near by at 105 Western Avenue, Allston. -

The Green Book a Collection of USCA History

The Green Book A Collection of U.S.C.A. History Guy Lillian and Krista Gasper 1971, 2002 Last Edited: March 26th, 2006 ii Contents I Cheap Place to Live 1 1 1933–1937 5 2 1937–1943 27 3 1943–1954 37 4 1954–1963 51 5 1964–1971 75 II Counterculture’s Last Stand 109 6 Introduction 113 7 What Was the U.S.C.A.? 115 8 How Did Barrington Hall Fit In? 121 9 What Were the Problems? 127 10 What is Barrington’s Legacy? 153 III Appendix 155 A Memorable Graffiti from Barrington Hall 157 B Reader Responses 159 iii iv CONTENTS About This Book The Green Book is a compilation of two sources. The first, Cheap Place to Live, was completed in 1971 by Guy Lillian as part of a U.S.C.A. funded project during the summer of 1971. The second, Counterculture’s Last Stand, was completed in 2002 by Krista Gasper as part of her undergraduate studies at Berkeley. Additional resources can be found at: • http://www.barringtonhall.org/ - A Barrington Hall web site run by Mahlen Morris. You can find a lot of pictures and other cool stuff here. • http://www.usca.org/ - The official U.S.C.A. web site. • http://ejinjue.org/projects/thegreenbook/ - The Green Book homepage. Warning: This book is not intended to be a definitive, com- plete and/or accurate reference. If you have any comments, suggestions or corrections, please email them to [email protected]. John Nishinaga Editor v vi CONTENTS Part I Cheap Place to Live 1 Introduction and Acknowledgments This history of the University Students Cooperative Associa- tion (U.S.C.A.) was funded through a grant by the Berkeley Consumers Cooperative to the U.S.C.A. -

Haas School of Business University of California, Berkeley S450 Student Services Building #1900 CA 94720-1900 Berkeley, • Position Themselves for a Successful Career

A summer business boot camp for non-business majors AA summersummer businessbusiness bootboot campcamp forfor non-businessnon-business majorsmajors PAID BASE US Postage BASE Presorted Standard Are you interested in business? Systems Inc. Postal Haas School of Business Do you want to get a great job after graduation? University of California, Berkeley Complement your degree with the BASE Summer Program from the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley. This intensive, six-week summer program is designed to teach the fundamentals of business to non-business, un- dergraduate students in arts, sciences, and engineering. Students in the BASE Summer Program • earn academic credit while developing top-notch business savvy • study at the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley, one of the top three undergraduate business programs in the US • meet business professionals around the San Francisco Bay Area • work with students from some of the most elite universities in the US BASE Summer Program Haas School of Business University of California, Berkeley S450 Student Services Building #1900 CA 94720-1900 Berkeley, • position themselves for a successful career www.haas.berkeley.edu/Undergrad/BASE/ www.haas.berkeley.edu/Undergrad/BASE/ Comments from BASE Alumni Why BASE? Why Berkeley? “The BASE program played an instrumental role in what in- dustry I chose to pursue by providing me with a well struc- tured fi rst experience into the different fi elds of business.” Young professionals today must have the skills necessary to For over 100 years, the Haas School of Business at the Univer- -Brian Sze, Stanford University operate in increasingly complex business environments. -

100709 WBB MG Text.Id2

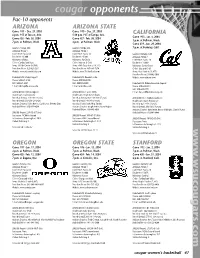

cougar opponents Pac-10 opponents ARIZONA ARIZONA STATE Game #11 – Dec. 29, 2003 Game #10 – Dec. 27, 2003 6 p.m. PST at Tucson, Ariz. 5:30 p.m. PST at Tempe, Ariz. CALIFORNIA Game #13 - Jan. 4, 2004 Game #26 - Feb. 26, 2004 Game #27 - Feb. 28, 2004 1 p.m. at Pullman, Wash. 7 p.m. at Pullman, Wash. 2 p.m. at Pullman, Wash. Game #19 – Jan. 29, 2004 Location: Tucson, Ariz. Location: Tempe, Ariz. 7 p.m. at Berkeley, Calif. Affiliation: NCAA 1 Affiliation: NCAA 1 Conference: Pacific-10 Conference: Pacific-10 Location: Berkeley, Calif. Enrollment: 35,000 Enrollment: 45,693 Affiliation: NCAA 1 Nickname: Wildcats Nickname: Sun Devils Conference: Pacific-10 Colors: Cardinal and Navy Colors: Maroon & Gold Enrollment: 33,000 Arena: McKale Center (14,545) Arena: Wells Fargo Arena (14,141) Nickname: Golden Bears Press Row Phone: 520-621-5291 Press Row Phone: 480-965-7274 Colors: Blue and Gold Website: www.arizonaathletics.com Website: www.TheSunDevils.com Arena: Haas Pavilion (11,877) Press Row Phone: 510-642-3098 Basketball SID: Mindy Claggett Basketball SID: Rhonda Lundin Website: www.calbears.com Phone: 520-621-4163 Phone: 480-965-9780 FAX: 520-621-2681 FAX: 480-965-5408 Basketball SID: Debbie Rosenfeld-Caparaz E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 510-642-3611 FAX: 510-643-7778 Athletic Director: Jim Livengood Athletic Director: Gene Smith E-mail: [email protected] Head Coach: Joan Bonvicini Head Coach: Charli Turner Thorne Record at Arizona: 214-139 (12 years) Record at Arizona State: 106-100 (7 years) Athletic -

3677 Hon. Dennis J. Kucinich Hon. Joe Baca

March 14, 2001 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 3677 seeking care at more than 40 types of out- TRIBUTE TO LEAMON KING The Delano Record dated May 15, 1956 patient settings. The office-based surgery stated the following: ‘‘King’s 9.3 Dash Brings standards were established specifically for sin- HON. JOE BACA Another Record to City. Delano became the gle sites of care with up to four physicians, OF CALIFORNIA home of two world champions Saturday when dentists or podiatrists. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Leamon King, local resident and former Dela- no High School track star, ran the 100 yards JCAHO evaluates and accredits nearly Wednesday, March 14, 2001 dash in 9.3 at the Fresno Relays to tie the 19,000 health care organizations and pro- Mr. BACA. Mr. Speaker, I would like to sa- world record. King’s victory brought another grams in the United States. Accreditation is lute Leamon King, of California. Leamon has world record to Delano, making it the home of recognized nationwide as a symbol of quality been recognized by Adelante, California Mi- one the fastest sprinters and the residence of that indicates that an organization meets cer- grant Leadership Council and American Le- Lon Spurrier, holder of the world record for the tain performance standards. JCAHO has cer- gion Merle Reed Post 124 as an outstanding 880. There is no city in the United States the tainly chosen a good place to start its accredi- individual who has made significant contribu- size of Delano, which can boast two world tation program of office-based surgery by tions to the improvement of education opportu- champions.’’ starting in Salinas. -

Schedule of Olympic Fencing Competitions 1896

Schedule of Olympic Fencing Competitions Event Days Competitors Nations 1896 - Athens Master's Foil 7 April 2 2 Venue: Zappeion Men's Foil Individual 7 April 8 2 Venue: Zappeion Men's Sabre Individual 9 April 5 3 Venue: Zappeion 1900 - Paris Men's Foil Individual 14-19, 21 May 54 9 Venue: La Grande Salle des Fêtes de l'Exposition/Galerie des Machines Master's Foil 22-25, 27-29 May 60 7 Venue: La Grande Salle des Fêtes de l'Exposition/Galerie des Machines Master's Epee 11-14 June 41 4 Venue: La Terrasse du Jeu de Paume aux Tuileries Men's Epee Individual 1-2, 5-7, 9-10, 13-14 June 103 12 Venue: La Terrasse du Jeu de Paume aux Tuileries Master's/Amateur's Epee 15 June 8 2 Venue: La Terrasse du Jeu de Paume aux Tuileries Men's Sabre Individual 19-20, 22,25 June 23 7 Venue: La Grande Salle des Fêtes de l'Exposition/Galerie des Machines Master's Sabre 23, 25-27 June 27 7 Venue: La Grande Salle des Fêtes de l'Exposition/Galerie des Machines 1904 - St. Louis Men's Epee Individual 7 September 5 3 Venue: Physical Culture Gymnasium next to Francis Field Sunday, May 06, 2012 Olympic Fencing Database Page 1 of 17 Schedule of Olympic Fencing Competitions Event Days Competitors Nations Men's Foil Individual 7 September 9 3 Venue: Physical Culture Gymnasium next to Francis Field Men's Foil Team 8 September 6 2 Venue: Physical Culture Gymnasium next to Francis Field Men's Sabre Individual 8 September 5 2 Venue: Physical Culture Gymnasium next to Francis Field Single Sticks 8 September 3 1 Venue: Physical Culture Gymnasium next to Francis Field 1906 - -

Front Matter

Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page vii © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Contents List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi INTRODUCTION The Cultural Cornerstone of the Ivory Tower 1 CHAPTER ONE Physical Culture, Discipline, and Higher Education in 1800s America 14 CHAPTER TWO Progressive Era Universities and Football Reform 40 CHAPTER THREE Psychologists: Body, Mind, and the Creation of Discipline 71 CHAPTER FOUR Social Scientists: Making Sport Safe for a Rational Public 93 CHAPTER FIVE Coaches: In the Disciplinary Arena 115 CHAPTER SIX Stadiums: Between Campus and Culture 139 CHAPTER SEVEN Academic Backlash in the Post–World War I Era 171 EPILOGUE A Circus or a Sideshow? 200 Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page viii © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. viii Contents Notes 207 Bibliography 269 Index 305 Ingrassia_Gridiron 11/6/15 12:22 PM Page ix © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Illustrations 1. Opening ceremony, Leland Stanford Junior University, October 1891 2 2. Walter Camp, captain of the Yale football team, circa 1880 35 3. Grant Field at Georgia Tech, 1920 41 4. Stagg Field at the University of Chicago 43 5. William Rainey Harper built the University of Chicago’s academic reputation and also initiated big-time athletics at the institution 55 6. Army-Navy game at the Polo Grounds in New York, 1916 68 7. G. T. W. Patrick in 1878, before earning his doctorate in philosophy under G. -

Original Article Specificity of Sport Real Estate Management

Journal of Physical Education and Sport ® (JPES), Vol 20 (Supplement issue 2), Art 162 pp 1165 – 1171, 2020 online ISSN: 2247 - 806X; p-ISSN: 2247 – 8051; ISSN - L = 2247 - 8051 © JPES Original Article Specificity of sport real estate management EWA SIEMIŃSKA Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, POLAND Published online: April 30, 2020 (Accepted for publication: April 15, 2020) DOI:10.7752/jpes.2020.s2162 Abstract The article deals with issues related to the management of the sports real estate market resources, with particular emphasis laid on sports stadiums. This market is not studied as often as the residential, office or commercial real estate market segments, which is why it is worth paying more attention to it. The evolution of the approach to sport, followed by the investing and use of sports real estate as a valuable resource of high value, means that increasing attention is being paid to the sports real estate market. The research objective of the article is to analyse and identify key areas of sports facility management, which the success of events organized on such facilities depends on, as well as to examine the requirements for sports facilities. The research used a lot of source information on the scope and standards of sports facility management as well as good practices and recommendations in this area. The following research methods were used in the article: a method of critical analysis of the subject literature on both the real estate market andthe sports market, as well as a descriptive and comparative methods to identify the evolution of the main directions of sports property management in the real estate market. -

Haas School of Business University of California-Berkeley Berkeley, CA

presents mbaMission’s Insider’s Guide Haas School of Business University of California-Berkeley Berkeley, CA 2017–2018 mbaMission can help you stand apart from the thousands of other MBA applicants! Your Partner in the MBA Admissions Process Our dedicated, full-time admissions advisors work one-on-one with business school candidates, helping them showcase their most compelling attributes and craft the strongest possible applications. World’s Leading Admissions Consulting Firm With more five-star reviews on GMAT Club than any other firm, we are recommended exclusively by both leading GMAT prep companies, Manhattan Prep and Kaplan GMAT. Free 30-Minute Consultation Visit www.mbamission.com/consult to schedule your complimentary half-hour session and start getting answers to your most pressing MBA application and admissions questions! We look forward to being your partner throughout the application process and beyond. mbamission.com [email protected] THE ONLY MUST-READ BUSINESS SCHOOL WEBSITE Oering more articles, series and videos on MBA programs and business schools than any other media outlet in the world, Poets&Quants has established a reputation for well-reported and highly-creative stories on the things that matter most to graduate business education prospects, students and alumnus. MBA Admissions Consultant Directory Specialized Master’s Directory Poets&Quants’ MBA Admissions Consultant Directory For graduate business degree seekers looking for a offers future applicants the opportunity specialization along with or apart from an MBA, to find a coach or consultant to assist in their Poets&Quants' Specialized Master's Directory helps candidacy into a top business school. Search by cost, you narrow your results by program type, location, experience, education, language and more.