Catherine Rigg, Lady Cavers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christopher Upton Phd Thesis

?@A374? 7; ?2<@@7?6 81@7; 2IQJRSOPIFQ 1$ APSON 1 @IFRJR ?TCMJSSFE GOQ SIF 3FHQFF OG =I3 BS SIF ANJUFQRJSX OG ?S$ 1NEQFVR '.-+ 5TLL MFSBEBSB GOQ SIJR JSFM JR BUBJLBCLF JN >FRFBQDI0?S1NEQFVR/5TLL@FWS BS/ ISSP/%%QFRFBQDI#QFPORJSOQX$RS#BNEQFVR$BD$TK% =LFBRF TRF SIJR JEFNSJGJFQ SO DJSF OQ LJNK SO SIJR JSFM/ ISSP/%%IEL$IBNELF$NFS%'&&()%(,)* @IJR JSFM JR PQOSFDSFE CX OQJHJNBL DOPXQJHIS STUDIES IN SCOTTISH LATIN by Christopher A. Upton Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St. Andrews October 1984 ýýFCA ýý£ s'i ý`q. q DRE N.6 - Parentibus meis conjugique meae. Iý Christopher Allan Upton hereby certify that this thesis which is approximately 100,000 words in length has been written by men that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. ý.. 'C) : %6 date .... .... signature of candidat 1404100 I was admitted as a research student under Ordinance No. 12 on I October 1977 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph. D. on I October 1978; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 1977 and 1980. $'ý.... date . .. 0&0.9 0. signature of candidat I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate to the degree of Ph. D. of the University of St Andrews and that he is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

'MELVILLIAN' REFORM in the SCOTTISH UNIVERSITIES James Kirk Τ Think', Wrote Martin Luther in 1520

'MELVILLIAN' REFORM IN THE SCOTTISH UNIVERSITIES James Kirk Τ think', wrote Martin Luther in 1520, 'that pope and emperor could have no better task than the reformation of the universities, just as there is nothing more devilishly mischievous than an unre- formed university'.1 Luther's appeal epitomised the search for a new educational programme—a programme of humanist teaching for the citizen as well as cleric—designed to replace the traditional values of scholasticism. This attack on teaching practice coincided with the assault on religious practice. Accepted beliefs in philos ophy and theology were rigorously re-examined: divine truth no longer seemed amenable to scholastic reasoning. The sixteenth century, as a whole, witnessed this renewed expression of the twin ideals of educational progress and eccle siastical reform. These two themes of renaissance and renewal helped shape the humanist tradition, and they were seen to represent much that was fundamental to the Christian life. These ideals, of course, were shared by Catholics and Protestants alike, though deep and irreconcilable divisions emerged over the differ ent ways through which these ideals should ultimately be attained. In Scotland, good Catholics like Archibald Hay and Archbishop Hamilton in St Andrews, Archbishop James Beaton in Glasgow, Bishop Reid of Orkney and Ninian Winyet, Linlithgow school master, all advocated a reform of morals and practice, and a revi val of learning as part of their reappraisal of Christian values within the existing house of God; and sound Protestants like John Knox, John Douglas in St Andrews, John Row in Perth and George Buchanan, a humanist of European reputation, demanded a far more radical solution in the expectation that this alone would pro vide the necessary firm foundation for the task of reconstructing God's house on earth.2 1 Luther's Pnmary Works, ed. -

SCOTTISH RECORD SOCIETY. C J^-'Chceq ~Ojud Capita 6Jxs$ of Yecurrd§> Ylt £93 J

tw mm* w • •• «•* m«! Bin • \: . v ;#, / (SCOTTISH RECORD SOCIETY. C J^-'ChceQ ~oJud Capita 6jXS$ Of Yecurrd§> Ylt £93 J SrwlmCj fcomininanotj THE Commissariot IRecorfc of Stirling, REGISTER OF TESTAMENTS 1 607- 1 800. EDITED BY FRANCIS J. GRANT, W.S., ROTHESAY HERALD AND LYON CLERK. EDINBURGH : PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY BY JAMES SKINNER & COMPANY. 1904. EDINBURGH : PRINTED BY JAMES SKINNER AND COMPANY. HfoO PREFACE. The Commissariot of Stirling included the following Parishes in Stirling- shire, viz. : —Airth, Bothkennar, Denny, Dunipace, Falkirk, Gargunnock, Kilsyth, Larbert, part of Lecropt, part of Logie, Muiravonside, Polmont, St. Ninian's, Slamannan, and Stirling; in Clackmannanshire, Alloa, Alva, and Dollar in Muckhart in Clackmannan, ; Kinross-shire, j Fifeshire, Carnock, Saline, and Torryburn. During the Commonwealth, Testa- ments of the Parishes of Baldernock, Buchanan, Killearn, New Kilpatrick, and Campsie are also to be found. The Register of Testaments is contained in twelve volumes, comprising the following periods : — I. i v Preface. Honds of Caution, 1648 to 1820. Inventories, 1641 to 181 7. Latter Wills and Testaments, 1645 to 1705. Deeds, 1622 to 1797. Extract Register Deeds, 1659 to 1805. Protests, 1705 to 1744- Petitions, 1700 to 1827. Processes, 1614 to 1823. Processes of Curatorial Inventories, 1786 to 1823. Miscellaneous Papers, 1 Bundle. When a date is given in brackets it is the actual date of confirmation, the other is the date at which the Testament will be found. When a number in brackets precedes the date it is that of the Testament in the volume. C0mmtssariot Jformrit %\\t d ^tirlitt0. REGISTER OF TESTAMENTS, 1607-1800. Abercrombie, Christian, in Carsie. -

The Admission of Ministers in the Church of Scotland

THE ADMISSION OF MINISTERS IN THE CHURCH OF SCOTLAND 1560-1652. A Study la Fresfcgrteriaa Ordination. DUNCAN SHAW. A Thesis presented to THE UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW, For the degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY, after study la THE DEPARTMENT OF ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY, April, 1976. ProQuest Number: 13804081 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13804081 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 X. A C KNQWLEDSMENT. ACKNOWLEDGMENT IS MADE OF TIE HELP AND ADVICE GIVEN TO THE AUTHOR OF THIS THESIS BY THE REV. IAN MUIRHEAD, M.A., B.D., SENIOR LECTURER IN ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW. II. TABLES OP CONTENTS PREFACE Paso 1 INTRODUCTION 3 -11 The need for Reformation 3 Clerical ignorance and corruption 3-4 Attempto at correction 4-5 The impact of Reformation doctrine and ideas 5-6 Formation of the "Congregation of Christ" and early moves towards reform 6 Desire to have the Word of God "truelie preached" and the Sacraments "rightlie ministred" 7 The Reformation in Scotland -

John Ogilvie: the Smoke and Mirrors of Confessional Politics

journal of jesuit studies 7 (2020) 34-46 brill.com/jjs John Ogilvie: The Smoke and Mirrors of Confessional Politics Allan I. Macinnes University of Strathclyde [email protected] Abstract The trial and execution of the Jesuit John Ogilvie in 1615 is located within diverse political contexts—Reformation and Counter-Reformation; British state formation; and the contested control of the Scottish Kirk between episcopacy and Presbyterian- ism. The endeavors of James vi and i to promote his ius imperium by land and sea did not convert the union of the crowns into a parliamentary union. However, he pressed ahead with British policies to civilize frontiers, colonize overseas and engage in war and diplomacy. Integral to his desire not to be beholden to any foreign power was his promotion of religious uniformity which resulted in a Presbyterian backlash against episcopacy. At the same time, the Scottish bishops sought to present a united Protes- tant front by implementing penal laws against Roman Catholic priests and laity, which led to Ogilvie being charged with treason for upholding the spiritual supremacy of the papacy over King James. Ogilvie’s martyrdom may stand in isolation, but it served to reinvigorate the Catholic mission to Scotland. Keywords British state formation – ius imperium – penal laws – recusancy – Presbyterians – episcopacy – lingering Catholicism – treason 1 Introduction Constant harassment by the Protestant Kirk in the wake of the Reformation, reinforced by threats of civil sanctions against regular clergy, practicing Ro- man Catholics and those who aided them, certainly restricted the scope for © Allan I. Macinnes, 2020 | doi:10.1163/22141332-00701003 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc-nd 4.0 license. -

The Percival J. Baldwin Puritan Collection

The Percival J. Baldwin Puritan Collection Accessing the Collection: 1. Anyone wishing to use this collection for research purposes should complete a “Request for Restricted Materials” form which is available at the Circulation desk in the Library. 2. The materials may not be taken from the Library. 3. Only pencils and paper may be used while consulting the collection. 4. Photocopying and tracing of the materials are not permitted. Classification Books are arranged by author, then title. There will usually be four elements in the call number: the name of the collection, a cutter number for the author, a cutter number for the title, and the date. Where there is no author, the cutter will be A0 to indicate this, to keep filing in order. Other irregularities are demonstrated in examples which follow. BldwnA <-- name of collection H683 <-- cutter for author O976 <-- cutter for title 1835 <-- date of publication Example. A book by the author Thomas Boston, 1677-1732, entitled, Human nature in its fourfold state, published in 1812. BldwnA B677 <-- cutter for author H852 <-- cutter for title 1812 <-- date of publication Variations in classification scheme for Baldwin Puritan collection Anonymous works: BldwnA A0 <---- Indicates no author G363 <---- Indicates title 1576 <---- Date Bibles: BldwnA B524 <---- Bible G363 <---- Geneva 1576 <---- Date Biographies: BldwnA H683 <---- cuttered on subject's name Z5 <---- Z5 indicates biography R633Li <---- cuttered on author's name, 1863 then first two letters of title Letters: BldwnA H683 <----- cuttered -

Women, Gender, and the Kirk Before the Covenant

JASON WHITE IRSS 45 (2020) 27 WOMEN, GENDER, AND THE KIRK BEFORE THE COVENANT Jason Cameron White, Appalachian State University ABSTRACT This article explores the ways women interacted with the Scottish kirk in the decades prior to the National Covenant of 1638, mainly focusing on urban areas especially Edinburgh and environs. The written records, especially those of the kirk session, are skewed toward punishing women who engaged in sin, especially sexual sins such as adultery and fornication. Indeed, these records show that while women’s behavior and speech was highly restricted and women were punished more frequently than men for their sexual behavior or for speaking out of turn, there were moments when women had a significant public voice, albeit one that was highly restricted and required male sanctioning. For example, women were often called on to testify before kirk sessions against those who had committed sins, even if the accused sinners were male or social superiors or both. Perhaps the most important moment where women used their male-sanctioned voice to speak out in public came at the Edinburgh Prayer Book Riots of 1637, which was led by women. This article argues that women were given the opportunity to act in public because the church had been characterized by many Scottish male preachers in gendered language – they called the church a “harlot mother” and a “whore” that needed correction. Therefore, the women of the Prayer Book Riot were sanctioned to speak out against a licentious sinner, much in the way women were called on to testify against sinners in front of kirk sessions. -

The Politics and Society of Glasgow, 1648-74 by William Scott Shepherd a Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

The Politics and Society of Glasgow, 1648-74 by William Scott Shepherd A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, to the Faculty of Arts in the University of Glasgow February 1978 ProQuest Number: 13804140 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13804140 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Contents Acknowledgments iii Abbreviations iv Notes on dating and currency vii Abstract viii Introduction to the society of Glasgow: its environment, constitution and institutions. 1 Prelude: the formation of parties in Glasgow, 1645-8 30 PART ONE The struggle for Kirk and King, 1648-52 Chapter 1 The radical ascendancy in Glasgow from October 1648 to the fall of the Western Association in December 1650. 52 Chapter II The time of trial: the revival of malignancy in Glasgow, and the last years of the radical Councils, December 1650 - March 1652. 70 PART TWO Glasgow under the Cromwellian Union, 1652-60 Chapter III A malignant re-assessment: the conservative rule in Glasgow, 1652-5. -

Re-Discovering Our Baptism

Re-Discovering Our Baptism H. Dane Sherrard It all began with Mrs. MacFarlane. I had just conducted morning worship at a super wee church in one of the tougher areas of Glasgow, a church at which I was serving as Interim Moderator. I was present at worship that morning because, following the service, I was to chair the Stated Annual Meeting of the congregation. I stood at the door and shook hands with all the folk as they came out of church, some to disappear into the community, most, I was glad to see, going into the hall where the meeting would shortly start. Quickly I went back into the sanctuary to collect my notes and as I did I was accosted by a woman in her forties, a woman I had never seen before but who was clearly waiting for me until everyone else had left so that she could say her piece. It took me all my time to persuade her to stop talking long enough to sit her down, and it was an effort to break into what she wanted to say to introduce myself and to learn that she was Mrs. MacFarlane. All she was interested in was whether I would 'do her wee one for her', whether I would 'christen her wean.' As I sat and made appropriate noises her story tumbled from her lips the-'wean' in question was not her daughter but her grand-daughter, the result of a chance encounter between her daughter and a ne'er-do well who was now out of her life and behind bars. -

THE LIFE of JOHN KNOX by Thomas M’Crie

THE LIFE OF JOHN KNOX by Thomas M’Crie Champions of Truth Ministry www.champs-of-truth.com 2 THE LIFE OF JOHN KNOX BY THOMAS M’CRIE 3 PREFACE The Reformation from popery marks an epoch unquestionably the most important in the history of modern Europe. The effects of the change which it produced, in religion, in manners, in politics, and in literature, continue to be felt at the present day. Nothing, surely, can be more interesting than an investigation of the history of that period, and of those men who were the instruments, under Providence, of accomplishing a revolution which has proved so beneficial to mankind. Though many able writers have employed their talents in tracing the causes and consequences of the Reformation, and though the leading facts respecting its progress in Scotland have been repeatedly stated, it occurred to me that the subject was by no means exhausted. I was confirmed in this opinion by a more minute examination of the ecclesiastical history of this country, which I began for my own satisfaction several years ago. While I was pleased at finding that there existed such ample materials for illustrating the history of the Scottish Reformation, I could not but regret that no one had undertaken to digest and exhibit the information on this subject which lay hid in manuscripts, and in books which are now little known or consulted. Not presuming, however, that I had the ability or the leisure requisite for executing a task of such difficulty and extent, I formed the design of drawing up memorials of our national Reformer, in which his personal history might be combined with illustrations of the progress of that great undertaking, in the advancement of which he acted so conspicuous a part. -

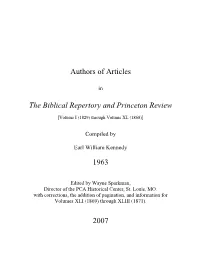

Authors of Articles in the Biblical Repertory and Princeton Review

Authors of Articles in The Biblical Repertory and Princeton Review [Volume I (1829) through Volume XL (1868)] Compiled by Earl William Kennedy 1963 Edited by Wayne Sparkman, Director of the PCA Historical Center, St. Louis, MO. with corrections, the addition of pagination, and information for Volumes XLI (1869) through XLIII (1871). 2007 INTRODUCTION This compilation is designed to make possible the immediate identification of the author(s) of any given article (or articles) in the Princeton Review. Unless otherwise stated, it is based on the alphabetical list of authors in the Index Volume from 1825 to 1868 (published in 1871), where each author‘s articles are arranged chronologically under his name. This Index Volume list in turn is based upon the recollections of several men closely associated with the Review. The following account is given of its genesis: ―Like the other great Reviews of the periods the writers contributed to its pages anonymously, and for many years no one kept any account of their labours. Dr. [Matthew B.] Hope [died 1859] was the first who attempted to ascertain the names of the writers in the early volumes, and he was only partially successful. With the aid of his notes, and the assistance of Dr. John Hall of Trenton, Dr. John C. Backus of Baltimore, and Dr. Samuel D. Alexander of New York, the companions and friends of the Editor and his early coadjutors, the information on this head here collected is as complete as it is possible now to be given.‖ (Index Volume, iii; of LSM, II, 271n; for meaning of symbols, see below) The Index Volume is usually but not always reliable. -

Sinclair of Dryden - a Cadet of St Clair of Roslin from Dryden Near Roslin in Midlothian Scotland

Sinclair of Dryden - a cadet of St Clair of Roslin from Dryden near Roslin in Midlothian Scotland William Sinclair 1st of Dryden (b.c1385 – bef. 1468) - third son of Henry St Clair 1st Earl of Orkney & Jean Haliburton . (Note 1) m. Agnes probably Agnes Chisholm (Note 2) A1 Laurence de Driden of Stirling & Perth - heir of Dryden oldest son (bc.1410/15 – d.1467 before his father) Keeper of the King’s accounts and auditor under the Comptroller of the royal household, Burgess of Perth - (Note 3) m. unknown. Possibility of a daughter of John de Fotheringham, Burgess of Perth (Note 4) B1 Agnes Dridane of Perth (bc.1440-1470) daughter & heiress of Laurence Dridane. (Note 5) m. Stephen Jaffray Burgess of Perth (Note 6) A2 Edward Sinclair 2nd of Dryden (d. after July 1496) 2nd son (Note 7) m1. unknown – probably a Crichton & possibly a daughter of Robert Crichton of Sanquhar in Dumfries & Kinnoull in Perth. (Note 8) B1. Sir John Sinclair 3rd of Dryden (bc.1455 – 1535) - Courtier & ambassador for James IV of Scotland & his wife Queen Margaret Tudor . (Note 9) m. (before 1496) Katherine Ramsay – daughter of William Ramsay of Polton, a cadet of Ramsay of Dalhousie (Note 10) C1 Edward Sinclair 4th of Dryden (d.1558-59) – son & heir of Sir John (Note 11) m1. Margaret Ramsay – daughter of David Ramsay of Bangour (Note 12) D1 Marion Sinclair (d. after 1564) only daughter and heir to Margaret Ramsay's portion of the Bangour estates (Note 12) m. John Henderson (b.1524 Fordell Fifeshire) of Bangour, Little Fordell & Dryden - son of George Henderson & Katherine Adamson (Note 13) E1 James Henderson (“apparent of Dryden” 1588) m2 (before 27 September 1529 ) Janet Henryson (Henderson) (d.