Treating Diabetes in Cameroon: a Comparative Study in Medical Anthropology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Verbal Extensions in Bantoid Languages and Their Relation to Bantu

VERBAL EXTENSIONS IN BANTOID LANGUAGES AND THEIR RELATION TO BANTU Roger Blench Paper prepared for circulation at the Conference on: Reconstructing Proto-Bantu Grammar University of Ghent, 19-23rd November, 2018 DRAFT ONLY: NOT TO BE QUOTED WITHOUT PERMISSION Roger Blench McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Correspondence to: 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Ans (00-44)-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7847-495590 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm Cambridge, 08 November 2018 Verbal extensions in Bantoid languages Roger Blench Draft TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction................................................................................................................................................. 1 2. The genetic classification of Bantoid ......................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Bantoid vs. Bantu.................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 Bantoid within [East] Benue-Congo ....................................................................................................... 3 2.3 The membership of Bantoid.................................................................................................................... 4 3. Bantoid verbal extensions.......................................................................................................................... -

Benakuma Council Development Plan (Cdp)

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace – Work – Fatherland Paix-Travail-Patrie ----------------- ----------------- MINISTERE DE l’ADMINISTRATION MINISTRY OF TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION TERRITORIALE ET DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND DECENTRALIZATION ----------------- ----------------- REGION DU NORD OUEST NORTH WEST REGION ----------------- ----------------- DEPARTEMENT DE LA MENCHUM MENCHUM DIVISION ----------------- ----------------- COMMUNE DE BENAKUMA BENAKUMA COUNCIL ----------------- BENAKUMA COUNCIL DEVELOPMENT PLAN (CDP) MARCH 2012 Benakumaa Council Development Plan-CDP Page 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The decentralization process is taking root in Cameroon. Councils are facing a formidable task to establish sustained and sustainable economic growth through increased performamce and productivity as the necessary basis for reducing poverty. An informed approach is to have a strategy to face the future challenges and missions of the council. The strategic instrument is the Council Development Plan (CDP) which is a document that aims to bring public service closer to the population by a total commitment of the council towards the population it serves. With the decentralization process, the administrative and institutional environment of council management, its human, material and financial resources will be called upon to increasingly contribute. Our space here is Benakuma Council which was created in 1993 by Decree No. 93/321 of 25 November 1993 relating to the creation of Urban and Rural Councils in Cameroon. The council area corresponds to the Menchum Valley Sub-Division, Menchum Division in the North-West Region of Cameroon. The council went operational in 1996 covering a surface area of 1 050 sq. km and a total population of 50 384 inhabitants as per the 2005 General Population and Housing Census. There are two main clans in the municipality: the Beba-Befang and the Esimbi clans. -

0 0 0 0 Acasa Program Final For

PROGRAM ABSTRACTS FOR THE 15TH TRIENNIAL SYMPOSIUM ON AFRICAN ART Africa and Its Diasporas in the Market Place: Cultural Resources and the Global Economy The core theme of the 2011 ACASA symposium, proposed by Pamela Allara, examines the current status of Africa’s cultural resources and the influence—for good or ill—of market forces both inside and outside the continent. As nation states decline in influence and power, and corporations, private patrons and foundations increasingly determine the kinds of cultural production that will be supported, how is African art being reinterpreted and by whom? Are artists and scholars able to successfully articulate their own intellectual and cultural values in this climate? Is there anything we can do to address the situation? WEDNESDAY, MARCH 23, 2O11, MUSEUM PROGRAM All Museum Program panels are in the Lenart Auditorium, Fowler Museum at UCLA Welcoming Remarks (8:30). Jean Borgatti, Steven Nelson, and Marla C. Berns PANEL I (8:45–10:45) Contemporary Art Sans Frontières. Chairs: Barbara Thompson, Stanford University, and Gemma Rodrigues, Fowler Museum at UCLA Contemporary African art is a phenomenon that transcends and complicates traditional curatorial categories and disciplinary boundaries. These overlaps have at times excluded contemporary African art from exhibitions and collections and, at other times, transformed its research and display into a contested terrain. At a moment when many museums with so‐called ethnographic collections are expanding their chronological reach by teasing out connections between traditional and contemporary artistic production, many museums of Euro‐American contemporary art are extending their geographic reach by globalizing their curatorial vision. -

Bambui Arts and Culture

Bambui Arts and Culture Bambui Arts and Culture By Mathias Alubafi Fubah Bambui Arts and Culture By Mathias Alubafi Fubah This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Mathias Alubafi Fubah All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0619-3 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0619-0 To the memory of MAMA NGWENGEH and MAMA FEHKIEUH CONTENTS Foreword .................................................................................................... ix Acknowledgement ...................................................................................... xi List of Objects .......................................................................................... xiii List of Tables ........................................................................................... xvii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One ................................................................................................. 7 The Name, Geography, Location and History Geographical Location History Chapter Two ............................................................................................. -

The Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon: a Geopolitical Analysis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by European Scientific Journal (European Scientific Institute) European Scientific Journal December 2019 edition Vol.15, No.35 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 The Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon: A Geopolitical Analysis Ekah Robert Ekah, Department of 'Cultural Diversity, Peace and International Cooperation' at the International Relations Institute of Cameroon (IRIC) Doi:10.19044/esj.2019.v15n35p141 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/esj.2019.v15n35p141 Abstract Anglophone Cameroon is the present-day North West and South West (English Speaking) regions of Cameroon herein referred to as No-So. These regions of Cameroon have been restive since 2016 in what is popularly referred to as the Anglophone crisis. The crisis has been transformed to a separatist movement, with some Anglophones clamoring for an independent No-So, re-baptized as “Ambazonia”. The purpose of the study is to illuminate the geopolitical perspective of the conflict which has been evaded by many scholars. Most scholarly write-ups have rather focused on the causes, course, consequences and international interventions in the crisis, with little attention to the geopolitical undertones. In terms of methodology, the paper makes use of qualitative data analysis. Unlike previous research works that link the unfolding of the crisis to Anglophone marginalization, historical and cultural difference, the findings from this paper reveals that the strategic location of No-So, the presence of resources, demographic considerations and other geopolitical parameters are proving to be responsible for the heightening of the Anglophone crisis in Cameroon and in favour of the quest for an independent Ambazonia. -

Etwi, Ntul, Nkwifoyn and Foyn: Sites, Objects and Human Beings in Conflict Resolution in Precolonial Kom (Cameroon)

Issue 3, April 2013 Etwi, Ntul, Nkwifoyn and Foyn: Sites, Objects and Human Beings in Conflict Resolution in Precolonial Kom (Cameroon) Walter Gam NKWI, PhD Abstract. Literature on conflict resolution the world over is replete. But literature on sites and instruments dealing with conflict resolution in Africa is largely inadequate and completely scarce in Cameroon historiography. The present paper attempts to fill this gap by focusing on the impor- tance and role of sites and human beings in resolving conflicts in pre-colonial Kom of the Northwest Cameroon, popularly known in colonial historiography as Bamenda Grassfields. The article confronts these sites and instruments, using mostly archival data and interviews with those who were involved in the activities, to prove that pre-colonial Africa had a well defined mechanism for resolving conflict long before European colonialism set foot on the continent. The article takes Kom as a case study. Keywords: Africa, Cameroon, Kom, Etwi, Ntul, Nkwifoyn, Foyn, Bamenda, Bamenda Grassfields. Introduction Etwi, Ntul, Nkwifoyn and Foyn are all found in local diction, itangikom. In the pre-colonial Kom these sites, objects, and humans were used in the arbitration, mediation, conciliation and reconciliation of conflicts at a micro and macro level. These sites and objects, as well as humans, constituted punctilious sites as well. Through them, Walter Gam NKWI, PhD the societal peace and tranquility was Department of History maintained. Therefore, conflict resolution University of Buea, Cameroon received an important place in society also E-mail: [email protected] as a result of the ingenuity of the indigenous Conflict Studies Quarterly people. -

A Sociolinguistic Survey of Bum

A Sociolinguistic Survey of Bum (Boyo Division, North West Province) Melinda Lamberty SIL International 2002 2 Contents 1INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND 1.2 TERMINOLOGY AND CLASSIFICATION 1.3 LOCATION AND POPULATION 1.4 LIVELIHOOD 1.5 RELIGION 1.6 HISTORY 2 PURPOSE AND APPROACH 2.1 PURPOSE OF THE SURVEY 2.2 METHODOLOGY 2.2.1 Dialect Intelligibility Testing 2.2.2 Group and Individual Interviews 2.2.3 Word Lists 2.3 HOW THE DATA WAS GATHERED 3RESULTS 3.1 DIALECT SITUATION 3.1.1 Variation within Bum 3.1.2 Range of Error 3.1.3 Lexical Comparison with Kom 3.2 MULTILINGUALISM 3.2.1 Languages Linguistically Close 3.2.2 Languages of Wider Communication 3.3 LANGUAGE VITALITY AND VIABILITY 3.3.1 Languages Used at Home, with Friends, and at Work 3.3.2 Languages Used in Public 3.3.3 Languages Used at School 3.3.4 Languages Used at Church 3.4 LANGUAGE ATTITUDES AND DEVELOPMENT 3.4.1 Attitudes toward the Mother Tongue 3.4.2 Attitudes toward Other Languages 3.4.3 Standardization Efforts 4 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 5 RECOMMENDATIONS APPENDICES APPENDIX A: RAPID APPRAISAL INTERVIEW APPENDIX B: RELIGIOUS LEADER QUESTIONNAIRE APPENDIX C: TEACHER/SCHOOL OFFICIAL QUESTIONNAIRE APPENDIX D: BUM PRACTICE TEXT APPENDIX E: KOM RTT TEXT APPENDIX F: BUM RTT SCORES APPENDIX G:120-ITEM WORD LIST REFERENCES 3 1 Introduction This survey took place January 22–28, 2001 in the Bum Subdivision of Boyo Division in the North West Province of Cameroon. The research team was comprised of Dorcas Chia (a mother-tongue speaker of Bum), Dr. -

Nasals and Low Tone in Grassfields Noun Class Prefixes Pius W

Nordic Journal of African Studies 26(1): 1–13 (2017) Nasals and Low Tone in Grassfields Noun Class Prefixes Pius W. Akumbu University of Buea, Cameroon & Larry M. Hyman University of California, Berkeley ABSTRACT As it is well known, noun class prefixes are low tone in Narrow Bantu and classes 1, 3, 4, 6(a), 9, and 10 have nasals (Meeussen 1967). However, just outside Narrow Bantu, noun class prefixes are usually high tone and the nasals are typically missing. A dichotomy is found in Grassfields Bantu where Eastern Grassfields resembles Narrow Bantu but the Ring and Momo sub-groups of Western Grassfields have high tone prefixes and lack nasals except sporadically. Drawing on data from Babanki and other Ring languages, we show that this relationship is not accidental. In a number of contexts where we expect a high tone prefix, a stem-initial NC cluster requires that it rather be low. We provide some speculations in this paper as to why nasals should be associated with low tone, an issue that has not been fully addressed in the literature on consonant types and tone. Keywords: nasals, tone, noun class, prefixes, Grassfields. 1. INTRODUCTION Over the past four decades, the study of noun classes in Grassfields Bantu languages has uncovered a number of issues concerning the tones of noun prefixes. As seen in Table 1 (next page), Proto (Narrow) Bantu, henceforth PB, is reconstructed with L tone noun prefixes, several of which also have a nasal consonant. The same *L tone reconstructions work for Eastern Grassfields Bantu (EGB), but not for Western Grassfields Bantu (WGB). -

The So-Called Royal Register of Bafut Within the Bafut Language Ecology

Chapter 3 The So-Called Royal Register of Bafut within the Bafut Language Ecology Language Ideologies and Multilingualism in the Cameroonian Grassfields Pierpaolo Di Carlo and Ayu’nwi N. Neba 1. INTRODUCTION: ARE LOWER FUNGOM AND LOWER CASAMANCE SUI GENERIS CASES? For decades, research on multilingualism in African countries has been mostly limited to urban settings (e.g., Scotton 1975, 1976; Myers-Scotton 1993; Dakubu 1997; Mc Laughlin 2009; Kamwangamalu 2012; Mba and Sadembouo 2012). More recently, studies stemming from the documentation of endangered languages have widened the scope of this research to include rural areas of the continent as well (Di Carlo 2016; Lüpke 2016; Cobbinah et al. 2016; Di Carlo, Good, and Ojong Diba 2019).1 This recent development is a welcome advance toward a greater geographic coverage of multilingual phenomena in Africa. Furthermore, approaching communicative practices in rural areas—such as Lower Fungom in northwest Cameroon and Lower Casamance in Senegal—means targeting areas that are characterized, on the one hand, by high degrees of linguistic diversity and, on the other, by the presence of persisting precolonial sociocultural traits. Ways of speaking in these areas, while surely not constituting a unitary phenomenon, are nonethe- less distinct from what is known from urban environments. A key component of these previously undocumented ways of speaking is that, according to the local metapragmatic knowledge, language choice allows the indexing of types of identities that have seldom, if ever, been described in the sociolinguistic literature on multilingualism in Africa. By default, one would expect that any given (socio)linguistic fact, including lan- guage choice, would be used to index a certain population and, by association 29 RL_03_DICARLO_C003_docbook_new_indd.indd 29 15-11-2019 9.03.42 PM 30 Pierpaolo Di Carlo and Ayu’nwi N. -

AR 08 SIL En (Page 2)

Annual Report Being Available for Language Development > Word of the Director Laying the foundation In 1992 my wife and I visited the Boyo Division for the first time. We researched the effectiveness of the Kom mother tongue education project. I rode around on the motorbike of the literacy coordinator of the language project, and I enjoyed the scenic vistas and the challenge of travelling on mountainous roads, but above all the wonderful hospitality of the people. My time there made it very clear to me that for many children mother ton- gue education is indispensable in order to succeed in life. Many of them could not read after years of schooling in English! I vowed that my own contribution to language development in Cameroon would be to help chil- dren learn to read and write in their own language first. I made myself available so that children would learn better English, would be proud of their own culture and would be able to help build a better Cameroon. 2 Fifteen years later, I am still just as committed to that goal . I am exci- ted to see mother tongue education flourish again in the Kom area. Over the years SIL helped establish the Operational Programme for Administration the Teaching of Languages in Cameroon (PROPELCA) in many lang- in Cameroon in December 2007 uages in Cameroon, hand in hand with organisations like the National Association of Cameroon Language Committees (NACAL- George Shultz, CO) and the Cameroon Association for Bible Translation and Literacy General Director Steve W. Wittig, Director of (CABTAL). It started as an experiment with mother tongue education General Administration but has grown beyond that. -

European Colonialism in Cameroon and Its Aftermath, with Special Reference to the Southern Cameroon, 1884-2014

EUROPEAN COLONIALISM IN CAMEROON AND ITS AFTERMATH, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE SOUTHERN CAMEROON, 1884-2014 BY WONGBI GEORGE AGIME P13ARHS8001 BEING A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, NIGERIA, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS (MA) DEGREE IN HISTORY SUPERVISOR PROFESSOR SULE MOHAMMED DR. JOHN OLA AGI NOVEMBER, 2016 i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this Dissertation titled: European Colonialism in Cameroon and its Aftermath, with Special Reference to the Southern Cameroon, 1884-2014, was written by me. It has not been submitted previously for the award of Higher Degree in any institution of learning. All quotations and sources of information cited in the course of this work have been acknowledged by means of reference. _________________________ ______________________ Wongbi George Agime Date ii CERTIFICATION This dissertation titled: European Colonialism in Cameroon and its Aftermath, with Special Reference to the Southern Cameroon, 1884-2014, was read and approved as meeting the requirements of the School of Post-graduate Studies, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, for the award of Master of Arts (MA) degree in History. _________________________ ________________________ Prof. Sule Mohammed Date Supervisor _________________________ ________________________ Dr. John O. Agi Date Supervisor _________________________ ________________________ Prof. Sule Mohammed Date Head of Department _________________________ ________________________ Prof .Sadiq Zubairu Abubakar Date Dean, School of Post Graduate Studies, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. iii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to God Almighty for His love, kindness and goodness to me and to the memory of Reverend Sister Angeline Bongsui who passed away in Brixen, in July, 2012. -

Cameroon Version 4 Clean#2

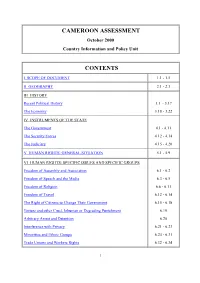

CAMEROON ASSESSMENT October 2000 Country Information and Policy Unit CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY 2.1 - 2.3 III HISTORY Recent Political History 3.1 - 3.17 The Economy 3.18 - 3.22 IV INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE The Government 4.1 - 4.11 The Security Forces 4.12 - 4.14 The Judiciary 4.15 - 4.20 V HUMAN RIGHTS: GENERAL SITUATION 5.1 - 5.9 VI HUMAN RIGHTS: SPECIFIC ISSUES AND SPECIFIC GROUPS Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.1 - 6.2 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.3 - 6.5 Freedom of Religion 6.6 - 6.11 Freedom of Travel 6.12 - 6.14 The Right of Citizens to Change Their Government 6.15 - 6.18 Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Punishment 6.19 Arbitrary Arrest and Detention 6.20 Interference with Privacy 6.21 - 6.23 Minorities and Ethnic Groups 6.24 - 6.31 Trade Unions and Workers Rights 6.32 - 6.34 1 Human Rights Groups 6.35 - 6.36 Women 6.36 - 6.41 Children 6.42 - 6.45 Treatment of Refugees 6.46 - 6.48 ANNEX A: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS Pages 19 - 22 ANNEX B: PROMINENT PEOPLE Page 23 ANNEX C: CHRONOLOGY Pages 24 - 27 ANNEX D: BIBLIOGRAPHY Pages 28 - 29 I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a variety of sources. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum determination process.