Shobhadissertation1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business SITUS Address Taxes Owed # 11828201655 PROPERTY HOLDING SERV TRUST 828 WABASH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28208 24.37 1 ROCK INVESTMENTS LLC

Business SITUS Address Taxes Owed # 11828201655 PROPERTY HOLDING SERV TRUST 828 WABASH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28208 24.37 1 ROCK INVESTMENTS LLC . 1101 BANNISTER PL CHARLOTTE NC 28213 510.98 1 STOP MAIL SHOP 8206 PROVIDENCE RD CHARLOTTE NC 28277 86.92 1021 ALLEN LLC . 1021 ALLEN ST CHARLOTTE NC 28205 419.39 1060 CREATIVE INC 801 CLANTON RD CHARLOTTE NC 28217 347.12 112 AUTO ELECTRIC 210 DELBURG ST DAVIDSON NC 28036 45.32 1209 FONTANA AVE LLC . FONTANA AV CHARLOTTE 22.01 1213 W MOREHEAD STREET GP LLC . 1207 W MOREHEAD ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 2896.87 1213 W MOREHEAD STREET GP LLC . 1201 W MOREHEAD ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 6942.12 1233 MOREHEAD LLC . 630 402 CALVERT ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 1753.48 1431 E INDEPENDENCE BLVD LLC . 1431 E INDEPENDENCE BV CHARLOTTE NC 28205 1352.65 160 DEVELOPMENT GROUP LLC . HUNTING BIRDS LN MECKLENBURG 444.12 160 DEVELOPMENT GROUP LLC . STEELE CREEK RD MECKLENBURG 2229.49 1787 JAMESTON DR LLC . 1787 JAMESTON DR CHARLOTTE NC 28209 3494.88 1801 COMMONWEALTH LLC . 1801 COMMONWEALTH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28205 9819.32 1961 RUNNYMEDE LLC . 5419 BEAM LAKE DR UNINCORPORATED 958.87 1ST METROPOLITAN MORTGAGE SUITE 333 3420 TORINGDON WY CHARLOTTE NC 28277 15.31 2 THE MAX SALON 10223 E UNIVERSITY CITY BV CHARLOTTE NC 28262 269.96 201 SOUTH TRYON OWNER LLC 201 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28202 396.11 201 SOUTH TRYON OWNER LLC 237 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28202 49.80 2010 TRYON REAL ESTATE LLC . 2010 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28203 3491.48 208 WONDERWOOD TREE PRESERVATION HO . -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Mark Twain's Theories of Morality. Frank C

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1941 Mark Twain's Theories of Morality. Frank C. Flowers Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Flowers, Frank C., "Mark Twain's Theories of Morality." (1941). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 99. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/99 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARK TWAIN*S THEORIES OF MORALITY A dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College . in. partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Prank C. Flowers 33. A., Louisiana College, 1930 B. A., Stanford University, 193^ M. A., Louisiana State University, 1939 19^1 LIBRARY LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY COPYRIGHTED BY FRANK C. FLOWERS March, 1942 R4 196 37 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The author gratefully acknowledges his debt to Dr. Arlin Turner, under whose guidance and with whose help this investigation has been made. Thanks are due to Professors Olive and Bradsher for their helpful suggestions made during the reading of the manuscript, E. C»E* 3 7 ?. 7 ^ L r; 3 0 A. h - H ^ >" 3 ^ / (CABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT . INTRODUCTION I. Mark Twain— philosopher— appropriateness of the epithet 1 A. -

Geologic Map of the Victoria Quadrangle (H02), Mercury

H01 - Borealis Geologic Map of the Victoria Quadrangle (H02), Mercury 60° Geologic Units Borea 65° Smooth plains material 1 1 2 3 4 1,5 sp H05 - Hokusai H04 - Raditladi H03 - Shakespeare H02 - Victoria Smooth and sparsely cratered planar surfaces confined to pools found within crater materials. Galluzzi V. , Guzzetta L. , Ferranti L. , Di Achille G. , Rothery D. A. , Palumbo P. 30° Apollonia Liguria Caduceata Aurora Smooth plains material–northern spn Smooth and sparsely cratered planar surfaces confined to the high-northern latitudes. 1 INAF, Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Rome, Italy; 22.5° Intermediate plains material 2 H10 - Derain H09 - Eminescu H08 - Tolstoj H07 - Beethoven H06 - Kuiper imp DiSTAR, Università degli Studi di Napoli "Federico II", Naples, Italy; 0° Pieria Solitudo Criophori Phoethontas Solitudo Lycaonis Tricrena Smooth undulating to planar surfaces, more densely cratered than the smooth plains. 3 INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Teramo, Teramo, Italy; -22.5° Intercrater plains material 4 72° 144° 216° 288° icp 2 Department of Physical Sciences, The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK; ° Rough or gently rolling, densely cratered surfaces, encompassing also distal crater materials. 70 60 H14 - Debussy H13 - Neruda H12 - Michelangelo H11 - Discovery ° 5 3 270° 300° 330° 0° 30° spn Dipartimento di Scienze e Tecnologie, Università degli Studi di Napoli "Parthenope", Naples, Italy. Cyllene Solitudo Persephones Solitudo Promethei Solitudo Hermae -30° Trismegisti -65° 90° 270° Crater Materials icp H15 - Bach Australia Crater material–well preserved cfs -60° c3 180° Fresh craters with a sharp rim, textured ejecta blanket and pristine or sparsely cratered floor. 2 1:3,000,000 ° c2 80° 350 Crater material–degraded c2 spn M c3 Degraded craters with a subdued rim and a moderately cratered smooth to hummocky floor. -

WEATHER-PROOFING Poems by Sandra Schor

“Weather-Proofing” Shenandoah. Fall, 1974: 18-19. WEATHER-PROOFING Poems by Sandra Schor Acknowledgments Some of the poems in this manuscript have previously appeared in The Beloit Poetry Journal, The Centennial Review, Colorado Quarterly, Confrontation, Florida Quarterly, The Journal of Popular Film, The Little Magazine, Montana Gothic, Ploughshares, Prairie Schooner, Shenandoah, Southern Poetry Review. Table of Contents I Weather-Proofing A Priest’s Mind . 1 Weather-Proofing . 2 Riding the Earth . 3 Small Consolation . 4 To the Poet as a Young Traveler . 6 The Fact of the Darkness . 7 Outside, Where Films End . 9 On Revisiting Tintern Abbey . 10 The Coming of the Ice: A Sestina . 11 House at the Beach . 13 Postcard from a Daughter in Crete . 15 Spinoza and Dostoevsky Tell Me About My Cousins . 16 Looking for Monday . 17 On the Absence of Moths Underseas . 18 II The Practical Life The Practical Life . 19 Taking the News . 21 In the Best of Health . 22 In the Center of the Soup . 23 Masks . 24 They Who Never Tire . 25 Decorum . 26 After Babi Yar . 27 Death of the Short-Term Memory . 29 Open-Ended . 30 Joys and Desires . 31 Snow on the Louvre . 32 Night Ferry to Helsinki . 33 The Unicorn and the Sea . 35 III Hovering Hovering . 36 Gestorben in Zurich . 37 In the Church of the Frari . 39 Death of an Audio Engineer . 40 For Georgio Morandi . 42 Piano Recital from Second Row Center . 43 In the Shade of Asclepius . 44 The Accident of Recovery . 45 On a Dish from the Ch’ing Dynasty . 46 Swallows on the Moon . -

Letters of Blood and Other Works in English

Letters of Blood and other works in English Göran Printz-Påhlson Robert Archambeau (ed.) Publisher: Open Book Publishers Year of publication: 2011 Published on OpenEdition Books: 11 January 2013 Serie: OBP collection Electronic ISBN: 9781906924584 http://books.openedition.org Printed version ISBN: 9781906924577 Number of pages: 210 Electronic reference PRINTZ-PÅHLSON, Göran. Letters of Blood and other works in English. New edition [online]. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2011 (generated 19 décembre 2018). Available on the Internet: <http:// books.openedition.org/obp/858>. ISBN: 9781906924584. © Open Book Publishers, 2011 Creative Commons - Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 UK: England & Wales - CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 UK Göran Printz-Påhlson Letters of Blood and other works in English EDITED BY ROBERT ARCHAMBEAU LETTERS OF BLOOD Letters of Blood and other works in English Göran Printz-Påhlson Edited by Robert Archambeau https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2011 Robert Archambeau; Foreword © 2011 Elinor Shaffer; ‘The Overall Wandering of Mirroring Mind’: Some Notes on Göran Printz-Påhlson © 2011 Lars-Håkan Svensson; Göran Printz-Påhlson’s original texts © 2011 Ulla Printz-Påhlson. Version 1.2. Minor edits made, May 2016. Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution- Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Göran Printz-Påhlson, Robert Archambeau (ed.), Letters of Blood. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0017 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www. -

Large Impact Basins on Mercury: Global Distribution, Characteristics, and Modification History from MESSENGER Orbital Data Caleb I

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 117, E00L08, doi:10.1029/2012JE004154, 2012 Large impact basins on Mercury: Global distribution, characteristics, and modification history from MESSENGER orbital data Caleb I. Fassett,1 James W. Head,2 David M. H. Baker,2 Maria T. Zuber,3 David E. Smith,3,4 Gregory A. Neumann,4 Sean C. Solomon,5,6 Christian Klimczak,5 Robert G. Strom,7 Clark R. Chapman,8 Louise M. Prockter,9 Roger J. Phillips,8 Jürgen Oberst,10 and Frank Preusker10 Received 6 June 2012; revised 31 August 2012; accepted 5 September 2012; published 27 October 2012. [1] The formation of large impact basins (diameter D ≥ 300 km) was an important process in the early geological evolution of Mercury and influenced the planet’s topography, stratigraphy, and crustal structure. We catalog and characterize this basin population on Mercury from global observations by the MESSENGER spacecraft, and we use the new data to evaluate basins suggested on the basis of the Mariner 10 flybys. Forty-six certain or probable impact basins are recognized; a few additional basins that may have been degraded to the point of ambiguity are plausible on the basis of new data but are classified as uncertain. The spatial density of large basins (D ≥ 500 km) on Mercury is lower than that on the Moon. Morphological characteristics of basins on Mercury suggest that on average they are more degraded than lunar basins. These observations are consistent with more efficient modification, degradation, and obliteration of the largest basins on Mercury than on the Moon. This distinction may be a result of differences in the basin formation process (producing fewer rings), relaxation of topography after basin formation (subduing relief), or rates of volcanism (burying basin rings and interiors) during the period of heavy bombardment on Mercury from those on the Moon. -

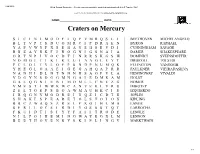

2D Mercury Crater Wordsearch V2

3/24/2019 Word Search Generator :: Create your own printable word find worksheets @ A to Z Teacher Stuff MAKE YOUR OWN WORKSHEETS ONLINE @ WWW.ATOZTEACHERSTUFF.COM NAME:_______________________________ DATE:_____________ Craters on Mercury SICINIMODFIQPVMRQSLJ BEETHOVEN MICHELANGELO BLTVPTSDUOMRCIPDRAEN BYRON RAPHAEL YAPVWYPXSEHAUEHSEVDI CUNNINGHAM SAVAGE RRZAYRKFJROGNIGSNAIA DAMER SHAKESPEARE ORTNPIVOCDTJNRRSKGSW DOMINICI SVEINSDOTTIR NOMGETIKLKEUIAAGLEYT DRISCOLL TOLSTOI PCLOLTVLOEPSNDPNUMQK ELLINGTON VANGOGH YHEGLOAAEIGEGAHQAPRR FAULKNER VIEIRADASILVA NANHIDLNTNNNHSAOFVLA HEMINGWAY VIVALDI VDGYNSDGGMNGAIEDMRAM HOLST GALQGNIEBIMOMLLCNEZG HOMER VMESTIWWKWCANVEKLVRU IMHOTEP ZELTOEPSBOAWMAUHKCIS IZQUIERDO JRQGNVMODREIUQZICDTH JOPLIN SHAKESPEARETOLSTOIOX KIPLING BBCZWAQSZRSLPKOJHLMA LANGE SFRLLOCSIRDIYGSSSTQT LARROCHA FKUIDTISIYYFAIITRODE LENGLE NILPOJHEMINGWAYEGXLM LENNON BEETHOVENRYSKIPLINGV MARKTWAIN 1/2 Mercury Craters: Famous Writers, Artists, and Composers: Location and Sizes Beethoven: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770−1827). German composer and pianist. 20.9°S, 124.2°W; Diameter = 630 km. Byron: Lord Byron (George Byron) (1788−1824). British poet and politician. 8.4°S, 33°W; Diameter = 106.6 km. Cunningham: Imogen Cunningham (1883−1976). American photographer. 30.4°N, 157.1°E; Diameter = 37 km. Damer: Anne Seymour Damer (1748−1828). English sculptor. 36.4°N, 115.8°W; Diameter = 60 km. Dominici: Maria de Dominici (1645−1703). Maltese painter, sculptor, and Carmelite nun. 1.3°N, 36.5°W; Diameter = 20 km. Driscoll: Clara Driscoll (1861−1944). American glass designer. 30.6°N, 33.6°W; Diameter = 30 km. Ellington: Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington (1899−1974). American composer, pianist, and jazz orchestra leader. 12.9°S, 26.1°E; Diameter = 216 km. Faulkner: William Faulkner (1897−1962). American writer and Nobel Prize laureate. 8.1°N, 77.0°E; Diameter = 168 km. Hemingway: Ernest Hemingway (1899−1961). American journalist, novelist, and short-story writer. 17.4°N, 3.1°W; Diameter = 126 km. -

In Search of Vyāsa: the Use of Greco-Roman Sources in Book 4 of the Mahābhārata

1 IN SEARCH OF VYĀSA: THE USE OF GRECO-ROMAN SOURCES IN BOOK 4 OF THE MAHĀBHĀRATA F WULFF ALONSO 2 © Fernando WULFF ALONSO In Search of Vyāsa: The Use of Greco-Roman Sources in Book 4 of the Mahābhārata 2020. This book can be freely copied and distributed for no commercial uses. Licence Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) Cover: Jaime Wulff 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book* has greatly benefited from the patience and curiosity of several people. I am especially grateful to the scholars who participated in the seminars held at the Universities of Rome-La Sapienza, in particular Raffaele Torella, at Cardiff University James Hegarty, at the University of Seville Alberto Bernabé Pajares, and Greg Wolff at the Institute of Classical Studies, University of London. I would also like to thank Cardiff University and the Institute of Classical Studies for accepting me as a visiting researcher. Other people who have been essential to the production of this book are Alf Hiltebeitel, Andrew Morrow, Nick Trillwood and my colleagues at the University of Malaga. I would also like to express my gratitude for the anonymous and, so often, thankless labour carried out by countless colleagues who generously make our work possible by curating the collections found on several key online databases such as, GRETIL (Göttingen Register of Electronic Texts in Indian Languages), University of Heidelberg’s DCS (Digital Corpus of Sanskrit) and Perseus Digital Library of Tufts University. And finally, there are two people who have been absolutely pivotal to this book. -

Investigating Sources of Mercury's Crustal

49th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2018 (LPI Contrib. No. 2083) 2109.pdf INVESTIGATING SOURCES OF MERCURY’S CRUSTAL MAGNETIC FIELD: FURTHER MAPPING OF MESSENGER MAGNETOMETER DATA. L. L. Hood1, J. S. Oliveira2,3, P. D. Spudis4, V. Galluzzi5, 1Lunar & Planetary Lab, 1629 E. University Blvd., Univ. of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA; [email protected], 2ESA/ESTEC, SCI-S, Keplerlaan 1, 2200 AG Noordwijk, Netherlands; 3CITEUC, Geophysi- cal & Astronomical Observatory, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal ([email protected] ); 4Lunar & Planetary Institute, USRA, Houston, TX; 5INAF, Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Rome, Italy. Introduction: A valuable data set for investigating the orbit tracks was accomplished in two substeps. crustal magnetism on Mercury was obtained by the First, a cubic polynomial was least-squares fitted to the NASA MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEo- raw radial component time series for each orbit pass. chemistry, and Ranging (MESSENGER) Discovery Second, the deviation from 5o running averages was mission during the final year of its existence [1]. Alti- calculated to eliminate wavelengths greater than about tude normalized maps of the crustal field covering part 215 km. At 60oN, the spacecraft altitude decreased of one side of the planet (90oE to 270oE; 35oN to75oN) from 35 km on March 16 to 5.2 km on April 2 when an have previously been constructed from low-altitude orbit correction burn occurred, increasing the altitude magnetometer data using an equivalent source dipole to 28 km. Several other orbit correction burns pre- (ESD) technique [2,3]. Results showed that the stron- vented the altitude at 60oN from decreasing below 8.8 gest crustal field anomalies in this region are concen- km during the period from April 2 to 23. -

Mercury: Radar Images of the Equatorial and Midlatitude Zones

Mercury: Radar images of the equatorial and midlatitude zones John K. Harmon a,∗,MartinA.Sladeb, Bryan J. Butler c, James W. Head III d, Melissa S. Rice a, Donald B. Campbell e a National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center, Arecibo Observatory, Arecibo, PR 00612, USA Fax: 787-878-1861; Tel: 787-878-2612 x284; Email: [email protected] b Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA Fax: 818-354-6825; Tel: 818-354-2765; Email: [email protected] c National Radio Astronomy Observatory, Socorro, NM 87801, USA Fax: 505-835-7027; Tel: 505-835-7261; Email: [email protected] d Department of Geological Sciences, Brown University, Providence, RI 02912, USA Fax: 401-863-3978; Tel: 401-863-2526; Email: James Head [email protected] e Department of Astronomy, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA Fax: 607-255-8803; Tel: 607-255-9580; Email: [email protected] Submitted to Icarus: June 15, 2006 Revised: September 20, 2006 - 50 manuscript pages 2tables 39 figures 2 Proposed running head: Mercury radar images Send correspondence and proofs to: John K. Harmon Arecibo Observatory HC3 Box 53995 Arecibo, PR 00612 Email: [email protected], Tel.: 787-878-2612 x284, Fax: 787-878-1861 3 Abstract. Radar imaging results for Mercury’s non-polar regions are presented. The dual- polarization, delay-Doppler images were obtained from several years of observations with the upgraded Arecibo S-band (λ12.6-cm) radar telescope. The images are dominated by radar- bright features associated with fresh impact craters. As was found from earlier Goldstone-VLA and pre-upgrade Arecibo imaging, three of the most prominent crater features are located in the Mariner-unimaged hemisphere. -

Gods Or Aliens? Vimana and Other Wonders

Gods or Aliens? Vimana and other wonders Parama Karuna Devi Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2017 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved ISBN-13: 978-1720885047 ISBN-10: 1720885044 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Table of contents Introduction 1 History or fiction 11 Religion and mythology 15 Satanism and occultism 25 The perspective on Hinduism 33 The perspective of Hinduism 43 Dasyus and Daityas in Rig Veda 50 God in Hinduism 58 Individual Devas 71 Non-divine superhuman beings 83 Daityas, Danavas, Yakshas 92 Khasas 101 Khazaria 110 Askhenazi 117 Zarathustra 122 Gnosticism 137 Religion and science fiction 151 Sitchin on the Annunaki 161 Different perspectives 173 Speculations and fragments of truth 183 Ufology as a cultural trend 197 Aliens and technology in ancient cultures 213 Technology in Vedic India 223 Weapons in Vedic India 238 Vimanas 248 Vaimanika shastra 259 Conclusion 278 The author and the Research Center 282 Introduction First of all we need to clarify that we have no objections against the idea that some ancient civilizations, and particularly Vedic India, had some form of advanced technology, or contacts with non-human species or species from other worlds. In fact there are numerous genuine texts from the Indian tradition that contain data on this subject: the problem is that such texts are often incorrectly or inaccurately quoted by some authors to support theories that are opposite to the teachings explicitly presented in those same original texts.