From Here to There: the Odyssey of the Liberal Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business SITUS Address Taxes Owed # 11828201655 PROPERTY HOLDING SERV TRUST 828 WABASH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28208 24.37 1 ROCK INVESTMENTS LLC

Business SITUS Address Taxes Owed # 11828201655 PROPERTY HOLDING SERV TRUST 828 WABASH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28208 24.37 1 ROCK INVESTMENTS LLC . 1101 BANNISTER PL CHARLOTTE NC 28213 510.98 1 STOP MAIL SHOP 8206 PROVIDENCE RD CHARLOTTE NC 28277 86.92 1021 ALLEN LLC . 1021 ALLEN ST CHARLOTTE NC 28205 419.39 1060 CREATIVE INC 801 CLANTON RD CHARLOTTE NC 28217 347.12 112 AUTO ELECTRIC 210 DELBURG ST DAVIDSON NC 28036 45.32 1209 FONTANA AVE LLC . FONTANA AV CHARLOTTE 22.01 1213 W MOREHEAD STREET GP LLC . 1207 W MOREHEAD ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 2896.87 1213 W MOREHEAD STREET GP LLC . 1201 W MOREHEAD ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 6942.12 1233 MOREHEAD LLC . 630 402 CALVERT ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 1753.48 1431 E INDEPENDENCE BLVD LLC . 1431 E INDEPENDENCE BV CHARLOTTE NC 28205 1352.65 160 DEVELOPMENT GROUP LLC . HUNTING BIRDS LN MECKLENBURG 444.12 160 DEVELOPMENT GROUP LLC . STEELE CREEK RD MECKLENBURG 2229.49 1787 JAMESTON DR LLC . 1787 JAMESTON DR CHARLOTTE NC 28209 3494.88 1801 COMMONWEALTH LLC . 1801 COMMONWEALTH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28205 9819.32 1961 RUNNYMEDE LLC . 5419 BEAM LAKE DR UNINCORPORATED 958.87 1ST METROPOLITAN MORTGAGE SUITE 333 3420 TORINGDON WY CHARLOTTE NC 28277 15.31 2 THE MAX SALON 10223 E UNIVERSITY CITY BV CHARLOTTE NC 28262 269.96 201 SOUTH TRYON OWNER LLC 201 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28202 396.11 201 SOUTH TRYON OWNER LLC 237 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28202 49.80 2010 TRYON REAL ESTATE LLC . 2010 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28203 3491.48 208 WONDERWOOD TREE PRESERVATION HO . -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Homer: an Arabic Portrait1

Edin Muftić Homer: An Arabic portrait1 Homer is rightfully seen as the first teacher of Hellenism, the poet who educated the Greek, who in turn educated Europe. But, as is well known, Europe doesn’t have a monopoly on Greek heritage. It was also present in the Islamic tradition, where it manifested itself differently. Apart from phi- losophy, mathematics, astronomy, medicine and pharmacology, Greek poetry, even if usually not translated, was also widely read among the Arab-Islamic intellectual elite. The author analyses the extent to which Homer’s works circulated, how well known were his poetics, and the influence his verses exerted during the heyday of Classical Arab-Islamic civilization. Keywords: Homer; translation movement; Al-Biruni; arabic poetry; Al-Farabi; Averroes INTRODUCTION The Greek and Arab epic tradition have much in common. Themes of tribal enmity, invasions and plunder, abduction of women, revenge, heroism, chivalry and love feature prom- inently in both traditions. While the Greeks have Hercules, Perseus, Theseus, Odysseus, Jason or Achilles, the Arabs have ʻAntar bin Šaddād (the “Arab Achilles”), Sayf bin ī Yazan, Az-Zīr Sālim and many others. When it comes to the actual performance of poetry, similarities be- Ḏ tween the two traditions are even greater. Homeric aoidos playing his lyre has a direct coun- terpart in Arab rawin playing his rababa. The Arab wandering poet often shares the fate of his Greek colleague (Imruʼ al-Qays, arafa and Al-Aʻšá, and Abū Nuwās and Al-Mutanabbī are the most famous examples). Greek tyrants who were famous for hosting poets like Ibycus, Anacre- Ṭ on, Simonides, Bacchylides or Pindar, while expelling others like Alcaeus, have a royal counter- part in An-Nuʻmān bin al-Mun ir, the ruler of Hira. -

Mark Twain's Theories of Morality. Frank C

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1941 Mark Twain's Theories of Morality. Frank C. Flowers Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Flowers, Frank C., "Mark Twain's Theories of Morality." (1941). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 99. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/99 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARK TWAIN*S THEORIES OF MORALITY A dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College . in. partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Prank C. Flowers 33. A., Louisiana College, 1930 B. A., Stanford University, 193^ M. A., Louisiana State University, 1939 19^1 LIBRARY LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY COPYRIGHTED BY FRANK C. FLOWERS March, 1942 R4 196 37 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The author gratefully acknowledges his debt to Dr. Arlin Turner, under whose guidance and with whose help this investigation has been made. Thanks are due to Professors Olive and Bradsher for their helpful suggestions made during the reading of the manuscript, E. C»E* 3 7 ?. 7 ^ L r; 3 0 A. h - H ^ >" 3 ^ / (CABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT . INTRODUCTION I. Mark Twain— philosopher— appropriateness of the epithet 1 A. -

The Challenge of Oral Epic to Homeric Scholarship

humanities Article The Challenge of Oral Epic to Homeric Scholarship Minna Skafte Jensen The Saxo Institute, Copenhagen University, Karen Blixens Plads 8, DK-2300 Copenhagen S, Denmark; [email protected] or [email protected] Received: 16 November 2017; Accepted: 5 December 2017; Published: 9 December 2017 Abstract: The epic is an intriguing genre, claiming its place in both oral and written systems. Ever since the beginning of folklore studies epic has been in the centre of interest, and monumental attempts at describing its characteristics have been made, in which oral literature was understood mainly as a primitive stage leading up to written literature. With the appearance in 1960 of A. B. Lord’s The Singer of Tales and the introduction of the oral-formulaic theory, the paradigm changed towards considering oral literature a special form of verbal art with its own rules. Fieldworkers have been eagerly studying oral epics all over the world. The growth of material caused that the problems of defining the genre also grew. However, after more than half a century of intensive implementation of the theory an internationally valid sociological model of oral epic is by now established and must be respected in cognate fields such as Homeric scholarship. Here the theory is both a help for readers to guard themselves against anachronistic interpretations and a necessary tool for constructing a social-historic context for the Iliad and the Odyssey. As an example, the hypothesis of a gradual crystallization of these two epics is discussed and rejected. Keywords: epic; genre discussion; oral-formulaic theory; fieldwork; comparative models; Homer 1. -

Geologic Map of the Victoria Quadrangle (H02), Mercury

H01 - Borealis Geologic Map of the Victoria Quadrangle (H02), Mercury 60° Geologic Units Borea 65° Smooth plains material 1 1 2 3 4 1,5 sp H05 - Hokusai H04 - Raditladi H03 - Shakespeare H02 - Victoria Smooth and sparsely cratered planar surfaces confined to pools found within crater materials. Galluzzi V. , Guzzetta L. , Ferranti L. , Di Achille G. , Rothery D. A. , Palumbo P. 30° Apollonia Liguria Caduceata Aurora Smooth plains material–northern spn Smooth and sparsely cratered planar surfaces confined to the high-northern latitudes. 1 INAF, Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Rome, Italy; 22.5° Intermediate plains material 2 H10 - Derain H09 - Eminescu H08 - Tolstoj H07 - Beethoven H06 - Kuiper imp DiSTAR, Università degli Studi di Napoli "Federico II", Naples, Italy; 0° Pieria Solitudo Criophori Phoethontas Solitudo Lycaonis Tricrena Smooth undulating to planar surfaces, more densely cratered than the smooth plains. 3 INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Teramo, Teramo, Italy; -22.5° Intercrater plains material 4 72° 144° 216° 288° icp 2 Department of Physical Sciences, The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK; ° Rough or gently rolling, densely cratered surfaces, encompassing also distal crater materials. 70 60 H14 - Debussy H13 - Neruda H12 - Michelangelo H11 - Discovery ° 5 3 270° 300° 330° 0° 30° spn Dipartimento di Scienze e Tecnologie, Università degli Studi di Napoli "Parthenope", Naples, Italy. Cyllene Solitudo Persephones Solitudo Promethei Solitudo Hermae -30° Trismegisti -65° 90° 270° Crater Materials icp H15 - Bach Australia Crater material–well preserved cfs -60° c3 180° Fresh craters with a sharp rim, textured ejecta blanket and pristine or sparsely cratered floor. 2 1:3,000,000 ° c2 80° 350 Crater material–degraded c2 spn M c3 Degraded craters with a subdued rim and a moderately cratered smooth to hummocky floor. -

WEATHER-PROOFING Poems by Sandra Schor

“Weather-Proofing” Shenandoah. Fall, 1974: 18-19. WEATHER-PROOFING Poems by Sandra Schor Acknowledgments Some of the poems in this manuscript have previously appeared in The Beloit Poetry Journal, The Centennial Review, Colorado Quarterly, Confrontation, Florida Quarterly, The Journal of Popular Film, The Little Magazine, Montana Gothic, Ploughshares, Prairie Schooner, Shenandoah, Southern Poetry Review. Table of Contents I Weather-Proofing A Priest’s Mind . 1 Weather-Proofing . 2 Riding the Earth . 3 Small Consolation . 4 To the Poet as a Young Traveler . 6 The Fact of the Darkness . 7 Outside, Where Films End . 9 On Revisiting Tintern Abbey . 10 The Coming of the Ice: A Sestina . 11 House at the Beach . 13 Postcard from a Daughter in Crete . 15 Spinoza and Dostoevsky Tell Me About My Cousins . 16 Looking for Monday . 17 On the Absence of Moths Underseas . 18 II The Practical Life The Practical Life . 19 Taking the News . 21 In the Best of Health . 22 In the Center of the Soup . 23 Masks . 24 They Who Never Tire . 25 Decorum . 26 After Babi Yar . 27 Death of the Short-Term Memory . 29 Open-Ended . 30 Joys and Desires . 31 Snow on the Louvre . 32 Night Ferry to Helsinki . 33 The Unicorn and the Sea . 35 III Hovering Hovering . 36 Gestorben in Zurich . 37 In the Church of the Frari . 39 Death of an Audio Engineer . 40 For Georgio Morandi . 42 Piano Recital from Second Row Center . 43 In the Shade of Asclepius . 44 The Accident of Recovery . 45 On a Dish from the Ch’ing Dynasty . 46 Swallows on the Moon . -

Letters of Blood and Other Works in English

Letters of Blood and other works in English Göran Printz-Påhlson Robert Archambeau (ed.) Publisher: Open Book Publishers Year of publication: 2011 Published on OpenEdition Books: 11 January 2013 Serie: OBP collection Electronic ISBN: 9781906924584 http://books.openedition.org Printed version ISBN: 9781906924577 Number of pages: 210 Electronic reference PRINTZ-PÅHLSON, Göran. Letters of Blood and other works in English. New edition [online]. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2011 (generated 19 décembre 2018). Available on the Internet: <http:// books.openedition.org/obp/858>. ISBN: 9781906924584. © Open Book Publishers, 2011 Creative Commons - Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 UK: England & Wales - CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 UK Göran Printz-Påhlson Letters of Blood and other works in English EDITED BY ROBERT ARCHAMBEAU LETTERS OF BLOOD Letters of Blood and other works in English Göran Printz-Påhlson Edited by Robert Archambeau https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2011 Robert Archambeau; Foreword © 2011 Elinor Shaffer; ‘The Overall Wandering of Mirroring Mind’: Some Notes on Göran Printz-Påhlson © 2011 Lars-Håkan Svensson; Göran Printz-Påhlson’s original texts © 2011 Ulla Printz-Påhlson. Version 1.2. Minor edits made, May 2016. Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution- Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. This license allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Göran Printz-Påhlson, Robert Archambeau (ed.), Letters of Blood. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0017 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www. -

Document Resume Ed 047 563 Fl 002 036 Author Title Institution Pub Date

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 047 563 FL 002 036 AUTHOR Willcock, M. M. TITLE The Present State of Homeric Studies. INSTITUTION Joint Association of Classical Teachers, Oxford (England). PUB DATE 67 NOTE 11p. JOURNAL CIT Didaskalos; v2 n2 p59-69 1967 EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Classical Literature, *Epics, *Greek, *Greek Literature, Historical Reviews, Humanism, Literature Reviews, Oral Reading, *Poetry, *Surveys, World Literature IDENTIFIEIAS *Homer, Iliad, Odyssey ABSTRACT A personal point of view concerning various aspects of Homerica characterizes this brief state-of-the-art report. Commentary is directed to:(1) first readers; (2) the Parry-Lord approach to the study of the "Iliad" and the "Odyssey" as representatives of a type of oral, formulaic, poetry;(3) analysts, unitarians, and neo-analysts; (4) recent publications by British scholars;(5) archaeology and history; (6) language and meter; and (7) the "Odyssey". (RL) fromDidaskalos; v2 n2 p59-69 1967 The present state of Homeric studies teN 1111 m.M. WILL COCK U.S. DEPARTMENT OF MOH. EDUCATION d WELFARE Nft OFFICE OF EDUCATION ".74P THIS DOCUMENT HAS BUN REPRODUCED EAACTLYAS RECEIVED ROM THE VIcV4 OD OPoivs PERSON OR ORGANIZAME eRI43!!th!!!!r:!I . V.1.14TI OF EDUCATION Ca STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE Um, POSITION OR POLICY. A select reading-list of Homerica, with a running com- Introduction mentary, cannot fail to be invidious. There is little chance that one person can fairly survey the vast fieldAll that I can offer is my own view-point, more literary than archaeological or linguistic. As to the limits of the survey, I have endeavoured to go far enough back in each separate aspect to clarify the present situation. -

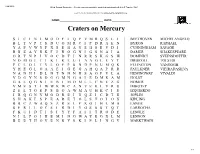

2D Mercury Crater Wordsearch V2

3/24/2019 Word Search Generator :: Create your own printable word find worksheets @ A to Z Teacher Stuff MAKE YOUR OWN WORKSHEETS ONLINE @ WWW.ATOZTEACHERSTUFF.COM NAME:_______________________________ DATE:_____________ Craters on Mercury SICINIMODFIQPVMRQSLJ BEETHOVEN MICHELANGELO BLTVPTSDUOMRCIPDRAEN BYRON RAPHAEL YAPVWYPXSEHAUEHSEVDI CUNNINGHAM SAVAGE RRZAYRKFJROGNIGSNAIA DAMER SHAKESPEARE ORTNPIVOCDTJNRRSKGSW DOMINICI SVEINSDOTTIR NOMGETIKLKEUIAAGLEYT DRISCOLL TOLSTOI PCLOLTVLOEPSNDPNUMQK ELLINGTON VANGOGH YHEGLOAAEIGEGAHQAPRR FAULKNER VIEIRADASILVA NANHIDLNTNNNHSAOFVLA HEMINGWAY VIVALDI VDGYNSDGGMNGAIEDMRAM HOLST GALQGNIEBIMOMLLCNEZG HOMER VMESTIWWKWCANVEKLVRU IMHOTEP ZELTOEPSBOAWMAUHKCIS IZQUIERDO JRQGNVMODREIUQZICDTH JOPLIN SHAKESPEARETOLSTOIOX KIPLING BBCZWAQSZRSLPKOJHLMA LANGE SFRLLOCSIRDIYGSSSTQT LARROCHA FKUIDTISIYYFAIITRODE LENGLE NILPOJHEMINGWAYEGXLM LENNON BEETHOVENRYSKIPLINGV MARKTWAIN 1/2 Mercury Craters: Famous Writers, Artists, and Composers: Location and Sizes Beethoven: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770−1827). German composer and pianist. 20.9°S, 124.2°W; Diameter = 630 km. Byron: Lord Byron (George Byron) (1788−1824). British poet and politician. 8.4°S, 33°W; Diameter = 106.6 km. Cunningham: Imogen Cunningham (1883−1976). American photographer. 30.4°N, 157.1°E; Diameter = 37 km. Damer: Anne Seymour Damer (1748−1828). English sculptor. 36.4°N, 115.8°W; Diameter = 60 km. Dominici: Maria de Dominici (1645−1703). Maltese painter, sculptor, and Carmelite nun. 1.3°N, 36.5°W; Diameter = 20 km. Driscoll: Clara Driscoll (1861−1944). American glass designer. 30.6°N, 33.6°W; Diameter = 30 km. Ellington: Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington (1899−1974). American composer, pianist, and jazz orchestra leader. 12.9°S, 26.1°E; Diameter = 216 km. Faulkner: William Faulkner (1897−1962). American writer and Nobel Prize laureate. 8.1°N, 77.0°E; Diameter = 168 km. Hemingway: Ernest Hemingway (1899−1961). American journalist, novelist, and short-story writer. 17.4°N, 3.1°W; Diameter = 126 km. -

Modeling and Mapping of the Structural Deformation of Large Impact Craters on the Moon and Mercury

MODELING AND MAPPING OF THE STRUCTURAL DEFORMATION OF LARGE IMPACT CRATERS ON THE MOON AND MERCURY by JEFFREY A. BALCERSKI Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY August, 2015 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Jeffrey A. Balcerski candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Committee Chair Steven A. Hauck, II James A. Van Orman Ralph P. Harvey Xiong Yu June 1, 2015 *we also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein ~ i ~ Dedicated to Marie, for her love, strength, and faith ~ ii ~ Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................1 2. Tilted Crater Floors as Records of Mercury’s Surface Deformation .....................4 2.1 Introduction ..............................................................................................5 2.2 Craters and Global Tilt Meters ................................................................8 2.3 Measurement Process...............................................................................12 2.3.1 Visual Pre-selection of Candidate Craters ................................13 2.3.2 Inspection and Inclusion/Exclusion of Altimetric Profiles .......14 2.3.3 Trend Fitting of Crater Floor Topography ................................16 2.4 Northern -

2RPP Contents

2RPP The Best of the Grammarians: Aristarchus of Samothrace on the Iliad Francesca Schironi https://www.press.umich.edu/8769399/best_of_the_grammarians University of Michigan Press, 2018 Contents Preface xvii 1. Main Sources and Method Followed in This Study xix 2. Other Primary Sources and Secondary Literature Used in This Study xx 3. Content, Goals, and Limitations of This Study xxiii Part 1. Aristarchus: Contexts and Sources 1.1. Aristarchus: Life, Sources, and Selection of Fragments 3 1. Aristarchus at Alexandria 3 2. The Aristarchean Tradition and the Venetus A 6 3. The Scholia Maiora to the Iliad and Erbse’s Edition 11 4. Aristarchus in the Scholia 14 4.1. Aristonicus at Work 15 4.2. Didymus at Work 18 4.3. Aristonicus versus Didymus 23 5. Selecting Aristarchus’ Fragments for This Study 26 6. Words and Content in Aristarchus’ Fragments 27 1.2. Aristarchus on Homer: Monographs, Editions, and Commentaries 30 1. Homeric Monographs 31 2. Editions (Ekdoseis) and Commentaries (Hypomnemata): The Evidence 35 2.1. Ammonius and the Homeric Ekdosis of Aristarchus 36 2.2. Ekdoseis and Hypomnemata: Different Reconstructions 38 3. The Impact of Aristarchus’ Recension on the Text of Homer 41 4. Ekdoseis and Hypomnemata: Some Tentative Conclusions 44 Part 2. Aristarchus at Work 2.1. Critical Signs: The Bridge between Edition and Commentary 49 1. The Critical Signs (σημεῖα) Used by the Alexandrians 49 2RPP The Best of the Grammarians: Aristarchus of Samothrace on the Iliad Francesca Schironi https://www.press.umich.edu/8769399/best_of_the_grammarians viiiUniversity of Michigan Press, 2018contents 2. Ekdosis, Hypomnema, and Critical Signs 52 3.