In Search of Vyāsa: the Use of Greco-Roman Sources in Book 4 of the Mahābhārata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business SITUS Address Taxes Owed # 11828201655 PROPERTY HOLDING SERV TRUST 828 WABASH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28208 24.37 1 ROCK INVESTMENTS LLC

Business SITUS Address Taxes Owed # 11828201655 PROPERTY HOLDING SERV TRUST 828 WABASH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28208 24.37 1 ROCK INVESTMENTS LLC . 1101 BANNISTER PL CHARLOTTE NC 28213 510.98 1 STOP MAIL SHOP 8206 PROVIDENCE RD CHARLOTTE NC 28277 86.92 1021 ALLEN LLC . 1021 ALLEN ST CHARLOTTE NC 28205 419.39 1060 CREATIVE INC 801 CLANTON RD CHARLOTTE NC 28217 347.12 112 AUTO ELECTRIC 210 DELBURG ST DAVIDSON NC 28036 45.32 1209 FONTANA AVE LLC . FONTANA AV CHARLOTTE 22.01 1213 W MOREHEAD STREET GP LLC . 1207 W MOREHEAD ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 2896.87 1213 W MOREHEAD STREET GP LLC . 1201 W MOREHEAD ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 6942.12 1233 MOREHEAD LLC . 630 402 CALVERT ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 1753.48 1431 E INDEPENDENCE BLVD LLC . 1431 E INDEPENDENCE BV CHARLOTTE NC 28205 1352.65 160 DEVELOPMENT GROUP LLC . HUNTING BIRDS LN MECKLENBURG 444.12 160 DEVELOPMENT GROUP LLC . STEELE CREEK RD MECKLENBURG 2229.49 1787 JAMESTON DR LLC . 1787 JAMESTON DR CHARLOTTE NC 28209 3494.88 1801 COMMONWEALTH LLC . 1801 COMMONWEALTH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28205 9819.32 1961 RUNNYMEDE LLC . 5419 BEAM LAKE DR UNINCORPORATED 958.87 1ST METROPOLITAN MORTGAGE SUITE 333 3420 TORINGDON WY CHARLOTTE NC 28277 15.31 2 THE MAX SALON 10223 E UNIVERSITY CITY BV CHARLOTTE NC 28262 269.96 201 SOUTH TRYON OWNER LLC 201 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28202 396.11 201 SOUTH TRYON OWNER LLC 237 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28202 49.80 2010 TRYON REAL ESTATE LLC . 2010 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28203 3491.48 208 WONDERWOOD TREE PRESERVATION HO . -

Kerngeschichte Des Mahabharatas

www.hindumythen.de Buch 1 Adi Parva Das Buch von den Anfängen Buch 2 Sabha Parva Das Buch von der Versammlungshalle Buch 3 Vana Parva Das Buch vom Wald Buch 4 Virata Parva Das Buch vom Aufenthalt am Hofe König Viratas Buch 5 Udyoga Parva Das Buch von den Kriegsvorbereitungen Buch 6 Bhishma Parva Das Buch von der Feldherrnschaft Bhishmas Buch 7 Drona Parva Das Buch von der Feldherrnschaft Dronas Buch 8 Karna Parva Das Buch von der Feldherrnschaft Karnas Buch 9 Shalya Parva Das Buch von der Feldherrnschaft Shalyas Buch 10 Sauptika Parva Das Buch vom nächtlichen Überfall Buch 11 Stri Parva Das Buch von den Frauen Buch 12 Shanti Parva Das Buch vom Frieden Buch 13 Anusasana Parva Das Buch von der Unterweisung Buch 14 Ashvamedha Parva Das Buch vom Pferdeopfer Buch 15 Ashramavasaka Parva Das Buch vom Besuch in der Einsiedelei Buch 16 Mausala Parva Das Buch von den Keulen Buch 17 Mahaprasthanika Parva Das Buch vom großen Aufbruch Buch 18 Svargarohanika Parva Das Buch vom Aufstieg in den Himmel www.hindumythen.de Für Ihnen unbekannte Begriffe und Charaktere nutzen Sie bitte mein Nachschlagewerk www.indische-mythologie.de Darin werden Sie auch auf detailliert erzählte Mythen im Zusammenhang mit dem jeweiligen Charakter hingewiesen. Vor langer Zeit kam in Bharata, wie Indien damals genannt wurde, der Weise Krishna Dvaipayana Veda Vyasa zur Welt. Sein Name bedeutet ‘Der dunkle (Krishna) auf einer Insel (Dvipa) Geborene (Dvaipayana), der die Veden (Veda) teilte (Vyasa). Krishna Dvaipayana war die herausragende Gestalt jener Zeit. Er ordnete die Veden und teilte sie in vier Teile, Rig, Sama, Yajur, Atharva. -

Microsoft Powerpoint

1 Ādi (225) 2 Sabhā (72) Ashvatthama's सय उवाच 3 Āranyaka (299) SjSanjaya said, 4 Virāta (67) Massacre Plan sañjaya uvāca 5 Udyoga Parva (197) 6 Bhīshma (117) Sauptika Parva 7 Drona (173) Chapters 1-5 8 Karna (69) 9 Shālya (64) 10 Sauptika - 18 chapters 11 Strī (27) 12 Shānti (353) 13 Anushāsana (154) 14 Ashvamedhika (96) 15 Āshramavāsika (47) 16 Mausala (9) 17 Mahāprasthānika (3) Swami Tadatmananda 18 Svargārohana (5) Arsha Bodha Center तािमुख े घारे े तता े िनावश ााै OthttiblihtOn that terrible night, Then, overcome by sl eep, tasmin rātri-mukhe ghore tato nidrāvaśaṁ prāptau दखशाु कसमवताे | कृ पभाजाे ै महारथा ै | immerse diidifd in pain and grief, the genera ls KiKripa and KitKritavarma duḥkha-śoka-samanvitāḥ kṛpa-bhojau mahārathau कृ तवमा कृ पा े ाणरै ् सखाचतावदे खाहाु ै Kritavarma, Kripa, and Ashvatthama who deserved happiness, not grief, kṛtavarmā kṛpo drauṇir sukhocitāvaduḥkhārhau उपापववशे समम् || िनषणा ै धरणीतले || sat down together. laid down to sleep on the ground. upopaviviśuḥ samam (1.28) niṣaṇṇau dharaṇī-tale (1.31) ाधामषे वश ााे सेष ु तषे ु काके षु ObOvercome by anger and diti impatience, While many crows were sl eep ing krodhāmarṣa-vaśaṁ prāpto supteṣuteṣukākeṣu ाणपे तु भारत | वधेष ु समतत | the son of Drona, O Dhr itarasht ra, soundly a ll around , droṇa-putras tu bhārata visrabdheṣu samantataḥ न लेभ े स त िना वै साऽपयसहसायातमे ् could not fall asleep, he suddenly saw the arrival na lebhe sa tu nidrāṁ vai so 'paśyat sahasāyāntam दमानाऽितमये ुना || उलूक घारदशे नम ् || burning with great anger. -

Geologic Map of the Victoria Quadrangle (H02), Mercury

H01 - Borealis Geologic Map of the Victoria Quadrangle (H02), Mercury 60° Geologic Units Borea 65° Smooth plains material 1 1 2 3 4 1,5 sp H05 - Hokusai H04 - Raditladi H03 - Shakespeare H02 - Victoria Smooth and sparsely cratered planar surfaces confined to pools found within crater materials. Galluzzi V. , Guzzetta L. , Ferranti L. , Di Achille G. , Rothery D. A. , Palumbo P. 30° Apollonia Liguria Caduceata Aurora Smooth plains material–northern spn Smooth and sparsely cratered planar surfaces confined to the high-northern latitudes. 1 INAF, Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Rome, Italy; 22.5° Intermediate plains material 2 H10 - Derain H09 - Eminescu H08 - Tolstoj H07 - Beethoven H06 - Kuiper imp DiSTAR, Università degli Studi di Napoli "Federico II", Naples, Italy; 0° Pieria Solitudo Criophori Phoethontas Solitudo Lycaonis Tricrena Smooth undulating to planar surfaces, more densely cratered than the smooth plains. 3 INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Teramo, Teramo, Italy; -22.5° Intercrater plains material 4 72° 144° 216° 288° icp 2 Department of Physical Sciences, The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK; ° Rough or gently rolling, densely cratered surfaces, encompassing also distal crater materials. 70 60 H14 - Debussy H13 - Neruda H12 - Michelangelo H11 - Discovery ° 5 3 270° 300° 330° 0° 30° spn Dipartimento di Scienze e Tecnologie, Università degli Studi di Napoli "Parthenope", Naples, Italy. Cyllene Solitudo Persephones Solitudo Promethei Solitudo Hermae -30° Trismegisti -65° 90° 270° Crater Materials icp H15 - Bach Australia Crater material–well preserved cfs -60° c3 180° Fresh craters with a sharp rim, textured ejecta blanket and pristine or sparsely cratered floor. 2 1:3,000,000 ° c2 80° 350 Crater material–degraded c2 spn M c3 Degraded craters with a subdued rim and a moderately cratered smooth to hummocky floor. -

Get Kindle # the Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Book

AYUQZYQDTHVG ^ Kindle ~ The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Book 10 Sauptika Parva The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Book 10 Sauptika Parva Filesize: 6.39 MB Reviews Merely no terms to spell out. It really is rally exciting throgh reading through period. Your daily life period is going to be enhance as soon as you complete looking over this ebook. (Yvette Marquardt) DISCLAIMER | DMCA MUSRXIQZAIHZ ~ eBook \\ The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Book 10 Sauptika Parva THE MAHABHARATA OF KRISHNA-DWAIPAYANA VYASA BOOK 10 SAUPTIKA PARVA Spastic Cat Press, United States, 2013. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 235 x 190 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****.The Mahabharata is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India. It is an epic narrative of the Kurukshetra War and the fates of the Kauravas and the Pandava princes as well as containing philosophical and devotional material, such as a discussion of the four goals of life. Here we have Sauptika Parva, the tenth, narrating the story of renunciation of throne of kingdom of Hastinapur by Yudhisthir and his journey with his wife and brothers throughout the country before final journey to heaven. Vyasa is a revered figure in Hindu traditions. He is a kala-Avatar or part-incarnation of God Vishnu. Vyasa is sometimes conflated by some Vaishnavas with Badarayana, the compiler of the Vedanta Sutras and considered to be one of the seven Chiranjivins. He is also the fourth member of the Rishi Parampara of the Advaita Guru Parampar of which Adi Shankara is the chief proponent. -

Investigating Sources of Mercury's Crustal

49th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2018 (LPI Contrib. No. 2083) 2109.pdf INVESTIGATING SOURCES OF MERCURY’S CRUSTAL MAGNETIC FIELD: FURTHER MAPPING OF MESSENGER MAGNETOMETER DATA. L. L. Hood1, J. S. Oliveira2,3, P. D. Spudis4, V. Galluzzi5, 1Lunar & Planetary Lab, 1629 E. University Blvd., Univ. of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA; [email protected], 2ESA/ESTEC, SCI-S, Keplerlaan 1, 2200 AG Noordwijk, Netherlands; 3CITEUC, Geophysi- cal & Astronomical Observatory, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal ([email protected] ); 4Lunar & Planetary Institute, USRA, Houston, TX; 5INAF, Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Rome, Italy. Introduction: A valuable data set for investigating the orbit tracks was accomplished in two substeps. crustal magnetism on Mercury was obtained by the First, a cubic polynomial was least-squares fitted to the NASA MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEo- raw radial component time series for each orbit pass. chemistry, and Ranging (MESSENGER) Discovery Second, the deviation from 5o running averages was mission during the final year of its existence [1]. Alti- calculated to eliminate wavelengths greater than about tude normalized maps of the crustal field covering part 215 km. At 60oN, the spacecraft altitude decreased of one side of the planet (90oE to 270oE; 35oN to75oN) from 35 km on March 16 to 5.2 km on April 2 when an have previously been constructed from low-altitude orbit correction burn occurred, increasing the altitude magnetometer data using an equivalent source dipole to 28 km. Several other orbit correction burns pre- (ESD) technique [2,3]. Results showed that the stron- vented the altitude at 60oN from decreasing below 8.8 gest crustal field anomalies in this region are concen- km during the period from April 2 to 23. -

El Mahabharata

EL MAHABHARATA — Vyasa Versión original: Mahabharata by Kamala Subramaniam. Maquetado con LATEX el 17 de enero de 2016. Preámbulo En mi primer viaje a la India, allá por 1984, encontré en una librería de Benarés la edición en doce tomos de la traducción del Mahabharata al inglés de Kisari Mohan Ganguli1. Por diversas razones no me era posible comprarlos en aquél momento, pero pensé que algún día lo haría. En aquella misma librería hojeé un libro sobre Gurdjieff en el que se decía sobre el Mahabharata: “Lo que no se encuentra aquí no se encuentra en ninguna parte.” Esta frase se me quedó grabada en la mente y no fué sino mucho más tarde que supe que estas palabras provienen del propio Mahabharata. En posteriores viajes a la India busqué en vano aquella versión de Ganguli que me había cautivado en Benarés. Sí encontré otras versiones, como la deliciosa traducción de partes escogidas de P. Lal, de apenas 250 páginas, de la que compré varios ejemplares y que leí con avidez y fascinación. Por fin, en 1996, encontré en una librería de Connaught Place (Nueva Delhi) lo que ahora era una edición faximil de aquella que había visto en mi primer viaje a la India (con la diferencia de que ahora estaba editada en rústica, en cuatro gruesos volúmenes). También vi en aquella librería una versión del Mahabharata en un sólo volumen, más grande y de unas 750 páginas que destacaba entre todas las versiones “resumidas” que había visto. Esta versión me atrajo porque parecía algo intermedio entre la hermosa versión de P. -

Gods Or Aliens? Vimana and Other Wonders

Gods or Aliens? Vimana and other wonders Parama Karuna Devi Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2017 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved ISBN-13: 978-1720885047 ISBN-10: 1720885044 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Table of contents Introduction 1 History or fiction 11 Religion and mythology 15 Satanism and occultism 25 The perspective on Hinduism 33 The perspective of Hinduism 43 Dasyus and Daityas in Rig Veda 50 God in Hinduism 58 Individual Devas 71 Non-divine superhuman beings 83 Daityas, Danavas, Yakshas 92 Khasas 101 Khazaria 110 Askhenazi 117 Zarathustra 122 Gnosticism 137 Religion and science fiction 151 Sitchin on the Annunaki 161 Different perspectives 173 Speculations and fragments of truth 183 Ufology as a cultural trend 197 Aliens and technology in ancient cultures 213 Technology in Vedic India 223 Weapons in Vedic India 238 Vimanas 248 Vaimanika shastra 259 Conclusion 278 The author and the Research Center 282 Introduction First of all we need to clarify that we have no objections against the idea that some ancient civilizations, and particularly Vedic India, had some form of advanced technology, or contacts with non-human species or species from other worlds. In fact there are numerous genuine texts from the Indian tradition that contain data on this subject: the problem is that such texts are often incorrectly or inaccurately quoted by some authors to support theories that are opposite to the teachings explicitly presented in those same original texts. -

Rationale for Bepicolombo Studies of Mercury's Surface and Composition

Space Sci Rev (2020) 216:66 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-020-00694-7 Rationale for BepiColombo Studies of Mercury’s Surface and Composition David A. Rothery1 · Matteo Massironi2 · Giulia Alemanno3 · Océane Barraud4 · Sebastien Besse5 · Nicolas Bott4 · Rosario Brunetto6 · Emma Bunce7 · Paul Byrne8 · Fabrizio Capaccioni9 · Maria Teresa Capria9 · Cristian Carli9 · Bernard Charlier10 · Thomas Cornet5 · Gabriele Cremonese11 · Mario D’Amore3 · M. Cristina De Sanctis9 · Alain Doressoundiram4 · Luigi Ferranti12 · Gianrico Filacchione9 · Valentina Galluzzi9 · Lorenza Giacomini9 · Manuel Grande13 · Laura G. Guzzetta9 · Jörn Helbert3 · Daniel Heyner14 · Harald Hiesinger15 · Hauke Hussmann3 · Ryuku Hyodo16 · Tomas Kohout17 · Alexander Kozyrev18 · Maxim Litvak18 · Alice Lucchetti11 · Alexey Malakhov18 · Christopher Malliband1 · Paolo Mancinelli19 · Julia Martikainen20,21 · Adrian Martindale7 · Alessandro Maturilli3 · Anna Milillo22 · Igor Mitrofanov18 · Maxim Mokrousov18 · Andreas Morlok15 · Karri Muinonen20,23 · Olivier Namur24 · Alan Owens25 · Larry R. Nittler26 · Joana S. Oliveira27,28 · Pasquale Palumbo29 · Maurizio Pajola11 · David L. Pegg1 · Antti Penttilä20 · Romolo Politi9 · Francesco Quarati30 · Cristina Re11 · Anton Sanin18 · Rita Schulz25 · Claudia Stangarone3 · Aleksandra Stojic15 · Vladislav Tretiyakov18 · Timo Väisänen20 · Indhu Varatharajan3 · Iris Weber15 · Jack Wright1 · Peter Wurz31 · Francesca Zambon22 Received: 20 December 2019 / Accepted: 13 May 2020 / Published online: 2 June 2020 © The Author(s) 2020 The BepiColombo mission -

Greek Mythology / Apollodorus; Translated by Robin Hard

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford 0X2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw with associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Robin Hard 1997 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published as a World’s Classics paperback 1997 Reissued as an Oxford World’s Classics paperback 1998 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organizations. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Apollodorus. [Bibliotheca. English] The library of Greek mythology / Apollodorus; translated by Robin Hard. -

Draupadi and Dhrishtadyumna

דראופדי http://img2.tapuz.co.il/CommunaFiles/34934883.pdf دراوبادي دروپدی द्रौपदी د ر وپد ی http://uh.learnpunjabi.org/default.aspx द्रौपदी ਦਰੋਪਤੀ http://h2p.learnpunjabi.org/default.aspx دروپتی فرشتہ ਦਰੋਪਤੀ ਫ਼ਰਰਸ਼ਤਾ http://g2s.learnpunjabi.org/default.aspx DRUPADA… Means "wooden pillar" or "firm footed" in Sanskrit. In the Hindu epic the 'Mahabharata' this is the name of a king of Panchala, the father of Draupadi and Dhrishtadyumna http://www.behindthename.com/name/drupada DRAUPADI Means "daughter of DRUPADA" in Sanskrit. http://www.behindthename.com/name/draupadi Draupadi - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Draupadi Draupadi From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Draupadi (Sanskrit: 6ौपदी , draupad ī, Sanskrit pronunciation: [d ̪ rəʊ pəd̪ i]) is described as the chief female Draupadi protagonist or heroine in the Hindu epic, Mahabharata .[1] According to the epic, she is the "fire born" daughter of Drupada, King of Panchala and also became the common wife of the five Pandavas. She was the most beautiful woman of her time. Draupadi had five sons; one by each of the Pandavas: Prativindhya from Yudhishthira, Sutasoma from Bheema, Srutakarma from Arjuna, Satanika from Nakula, and Srutasena from Sahadeva. Some people say that she too had two daughters after the Upapandavas, Shutanu from Yudhishthira and Pragiti from Arjuna although this is a debatable concept in the Mahabharata. Draupadi is considered as one of the Panch-Kanyas or Five Virgins. [2] She is also venerated as a village goddess Draupadi Amman. Draupadi, -

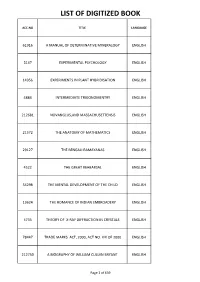

List of Digitized Book

LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK ACC.NO TITLE LANGUAGE 61916 A MANUAL OF DETERMINATIVE MINERALOGY ENGLISH 5147 EXPERIMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY ENGLISH 14956 EXPERIMENTS IN PLANT HYBRIDISATION ENGLISH 4884 INTERMEDIATE TRIGONOMENTRY ENGLISH 212681 NOVANGLUS,AND MASSACHUSETTENSIS ENGLISH 21572 THE ANATOMY OF MATHEMATICS ENGLISH 29127 THE BENGALI RAMAYANAS ENGLISH 4522 THE GREAT REHEARSAL ENGLISH 54298 THE MENTAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE CHILD ENGLISH 13624 THE ROMANCE OF INDIAN EMBROADERY ENGLISH 4735 THEORY OF X-RAY DIFFRACTION IN CRYSTALS ENGLISH 78447 TRADE MARKS ACT, 2000, ACT NO. XIX OF 2000 ENGLISH 212750 A BIOGRAPHY OF WILLIAM CULLEN BRYANT ENGLISH Page 1 of 639 LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK 1189 A BOOK OF BOTH SPORTS ENGLISH CA_3228 A BOOK OF WORDS ENGLISH 5376 A BRIEF BIOLOGY ENGLISH ASL_234 A BRIEF HISTORY OF SHAH-HAMDAN-MOSQUE ENGLISH 9877 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES ENGLISH 153159 A CATALOGUE OF INDIAN SYNONMES ENGLISH 10631 A CHANGED MAN AND OTHER TALES ENGLISH 14410 A CHAUCER SELECTION ENGLISH 120567 A CHOICE OF KIPLING'S VERSE ENGLISH 59529 A CHRISTMAS CAROL ENGLISH 20825 A CHRISTMAS GARLAND ENGLISH 973 A COAT OF MANY COLOURS ENGLISH 491019 A COLLECTION OF PAPERS ENGLISH 14573 A COMMERCIAL COURSE FOR FOREIGN STUDENTS ENGLISH Page 2 of 639 LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK 73364 A CONCISE ECONOMIC HISTORY OF BRITAIN ENGLISH A CONTRIBUTION TO THE THEORY OF THE TRADE 134801 ENGLISH CYCLE 20121 A COURSE IN GENERAL CHEMISTRY ENGLISH 162546 A COURSE OF MODERN ANALYSIS ENGLISH 20368 A COURSE OF STUDY IN CHEMICAL PRINCIPLES ENGLISH 70174 A CRITICAL HISTORY OF ENGLISH