Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long Way Home

24 WacanaWacana Vol. Vol. 18 No.18 No. 1 (2017): 1 (2017) 24-37 Long way home The life history of Chinese-Indonesian migrants in the Netherlands1 YUMI KITAMURA ABSTRACT The purpose of this paper is to trace the modern history of Indonesia through the experience of two Chinese Indonesians who migrated to the Netherlands at different periods of time. These life stories represent both postcolonial experiences and the Cold War politics in Indonesia. The migration of Chinese Indonesians since the beginning of the twentieth century has had long history, however, most of the previous literature has focused on the experiences of the “Peranakan” group who are not representative of various other groups of Chinese Indonesian migrants who have had different experiences in making their journey to the Netherlands. This paper will present two stories as a parallel to the more commonly known narratives of the “Peranakan” experience. KEYWORDS September 30th Movement; migration; Chinese Indonesians; cultural revolution; China; Curacao; the Netherlands. 1. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this paper is to trace the modern history of Indonesia through the experience of Chinese Indonesians who migrated to the Netherlands after World War II. The study of overseas Chinese tends to challenge the boundaries of the nation-state by exploring the ideas of transnational identities 1 Some parts of this article are based on the rewriting of a Japanese article: Kitamura, Yumi. 2014. “Passage to the West; The life history of Chinese Indonesians in the Netherlands“ (in Japanese), Chiiki Kenkyu 14(2): 219-239. Yumi Kitamura is an associate professor at the Kyoto University Library. -

Forest, Resources and People in Bulungan Elements for a History of Settlement, Trade, and Social Dynamics in Borneo, 1880-2000

CIFOR Forest, Resources and People in Bulungan Elements for a History of Settlement, Trade, and Social Dynamics in Borneo, 1880-2000 Bernard Sellato Forest, Resources and People in Bulungan Elements for a History of Settlement, Trade and Social Dynamics in Borneo, 1880-2000 Bernard Sellato Cover Photo: Hornbill carving in gate to Kenyah village, East Kalimantan by Christophe Kuhn © 2001 by Center for International Forestry Research All rights reserved. Published in 2001 Printed by SMK Grafika Desa Putera, Indonesia ISBN 979-8764-76-5 Published by Center for International Forestry Research Mailing address: P.O. Box 6596 JKPWB, Jakarta 10065, Indonesia Office address: Jl. CIFOR, Situ Gede, Sindang Barang, Bogor Barat 16680, Indonesia Tel.: +62 (251) 622622; Fax: +62 (251) 622100 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.cifor.cgiar.org Contents Acknowledgements vi Foreword vii 1. Introduction 1 2. Environment and Population 5 2.1 One Forested Domain 5 2.2 Two River Basins 7 2.3 Population 9 Long Pujungan District 9 Malinau District 12 Comments 13 3. Tribes and States in Northern East Borneo 15 3.1 The Coastal Polities 16 Bulungan 17 Tidung Sesayap 19 Sembawang24 3.2 The Stratified Groups 27 The Merap 28 The Kenyah 30 3.3 The Punan Groups 32 Minor Punan Groups 32 The Punan of the Tubu and Malinau 33 3.4 One Regional History 37 CONTENTS 4. Territory, Resources and Land Use43 4.1 Forest and Resources 44 Among Coastal Polities 44 Among Stratified Tribal Groups 46 Among Non-Stratified Tribal Groups 49 Among Punan Groups 50 4.2 Agricultural Patterns 52 Rice Agriculture 53 Cash Crops 59 Recent Trends 62 5. -

RSPO Public Summary Report Template

Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil Public Summary Report Report no. : RSPO P&C – IC 19113 against the RSPO Prin- 2013 INA-NI, 2016 NG-NI, 2017 Generic, 2018 ciples & Cri- 2018 MY-NI, 2015 GH-NI, 2015 teria RSPO Supply Chain Certification Standard, 2014 (Rev. June 2017) Group Certification of FFB Production 2016 Rev.2018 RSPO Supply Chain Certification Standard, 2014 (Rev. June 2017) PT Dharma Satya Nusantara Palm Oil Mill 6 East Kutai District, East Kalimantan Date of assessment : September 02 to 06, 2019 Report prepared by: Dian S Soeminta (RSPO Lead Auditor) Certification decision by: I Nyoman Susila (Director of TUV Rheinland Indonesia) Certification Body: PT TUV Rheinland Indonesia Menara Karya, 10th Floor Jl. H.R. Rasuna Said Block X-5 Kav.1-2 Jakarta 12950,Indonesia Tel: +62 21 57944579 Fax: +62 21 57944575 www.tuv.com/id Accreditatation number : ASI-ACC-061 & 06 June 2024 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 SCOPE OF CERTIFICATION ASSESSMENT. .............................................................................................. 3 2.0. DESCRIPTION OF CERTIFIATION UNIT ..................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Location .................................................................................................................................................. 3 2.2. Maps ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 2.3. Supply Base Composition .................................................................................................................... -

TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 405 265 SO 026 916 TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995. Participants' Reports. INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC.; Malaysian-American Commission on Educational Exchange, Kuala Lumpur. PUB DATE 95 NOTE 321p.; Some images will not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reports Descriptive (141) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Asian History; *Asian Studies; Cultural Background; Culture; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; *Global Education; Human Geography; Instructional Materials; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies; *World Geography; *World History IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Malaysia ABSTRACT These reports and lesson plans were developed by teachers and coordinators who traveled to Malaysia during the summer of 1995 as part of the U.S. Department of Education's Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program. Sections of the report include:(1) "Gender and Economics: Malaysia" (Mary C. Furlong);(2) "Malaysia: An Integrated, Interdisciplinary Social Studies Unit for Middle School/High School Students" (Nancy K. Hof);(3) "Malaysian Adventure: The Cultural Diversity of Malaysia" (Genevieve M. Homiller);(4) "Celebrating Cultural Diversity: The Traditional Malay Marriage Ritual" (Dorene H. James);(5) "An Introduction of Malaysia: A Mini-unit for Sixth Graders" (John F. Kennedy); (6) "Malaysia: An Interdisciplinary Unit in English Literature and Social Studies" (Carol M. Krause);(7) "Malaysia and the Challenge of Development by the Year 2020" (Neale McGoldrick);(8) "The Iban: From Sea Pirates to Dwellers of the Rain Forest" (Margaret E. Oriol);(9) "Vision 2020" (Louis R. Price);(10) "Sarawak for Sale: A Simulation of Environmental Decision Making in Malaysia" (Kathleen L. -

PROCEEDINGS, INDONESIAN PETROLEUM ASSOCIATION Forty-First Annual Convention & Exhibition, May 2017

IPA17-722-G PROCEEDINGS, INDONESIAN PETROLEUM ASSOCIATION Forty-First Annual Convention & Exhibition, May 2017 “SOME NEW INSIGHTS TO TECTONIC AND STRATIGRAPHIC EVOLUTION OF THE TARAKAN SUB-BASIN, NORTH EAST KALIMANTAN, INDONESIA” Sudarmono* Angga Direza* Hade Bakda Maulin* Andika Wicaksono* INTRODUCTION in Tarakan island and Sembakung and Bangkudulis in onshore Northeast Kalimantan. This paper will discuss the tectonic and stratigraphic evolution of the Tarakan sub-basin, primarily the On the other side, although the depositional setting fluvio-deltaic deposition during the Neogene time. in the Tarakan sub-basin is deltaic which is located The Tarakan sub-basin is part of a sub-basin complex to the north of the Mahakam delta, people tend to use which includes the Tidung, Berau, and Muaras sub- the Mahakam delta as a reference to discuss deltaic basins located in Northeast Kalimantan. In this depositional systems. This means that the Mahakam paper, the discussion about the Tarakan sub-basin delta is more understood than the delta systems in the also includes the Tidung sub-basin. The Tarakan sub- Tarakan sub-basin. The Mahakam delta is single basin is located a few kilometers to the north of the sourced by the Mahakam river which has been famous Mahakam delta. To the north, the Tarakan depositing a stacked deltaic sedimentary package in sub-basin is bounded by the Sampoerna high and to one focus area to the Makasar Strait probably since the south it is bounded by the Mangkalihat high. The the Middle Miocene. The deltaic depositional setting Neogene fluvio-deltaic sediment in the Tarakan sub- is confined by the Makasar Strait which is in such a basin is thinning to the north to the Sampoerna high way protecting the sedimentary package not to and to the south to the Mangkalihat high. -

Revealing Willingness to Pay and Willingness to Work to Avoid Deforestation

Revealing Willingness to Pay and Willingness to Work to Avoid Deforestation and Forest Degradation Using the Contingent Valuation Method: Evidences from Indonesia by Akhmad Solikin Supervised by Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Löwenstein A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in International Development Studies Institute of Development Research and Development Policy Ruhr University Bochum, Germany 2015 Acknowledgements There are many people contributing in different ways for the completion of this dissertation. First and foremost, I would like to express my great appreciation to my first supervisor, Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Löwenstein, who providing scientific supports and advices during my academic journey. I also would like to offer my special thanks to my second supervisor, Prof. Dr. Helmut Karl for his guidance and valuable comments. I am also thankful to Prof. Dr. Markus Kaltenborn as the chairperson in my oral examination. I also thank many people in IEE for their supports. I thank Dr. Anja Zorob and Dr. Katja Bender as current and former PhD Coordinator who help me navigating though administrative process during my study in Bochum. I am also thankful to administrative supports provided by IEE secretariat. For Welcome Center of RUB for providing supports in dealing with legal and cultural matters as well as for Research School of RUB which provide additional workshops, I would like to thanks. I am also grateful for fruitful discussions and talks with colleagues of PhD students especially Mr. Naveed Iqbal Shaikh, Mr. Elias Fanta, Mr. Elkhan Sadik-Zada, Mr. Abate Mekuriaw Bizuneh, Mr. Beneberu Assefa Wondimagegnhu, Mr. Charlton C. -

Conflict Timber: Dimensions of the Problem in Asia and Africa Volume II Table of Contents

Final Report Submitted to the United States Agency for International Development Conflict Timber: Dimensions of the Problem in Asia and Africa Volume II Asian Cases Authors James Jarvie, Forester Ramzy Kanaan, Natural Resources Management Specialist Michael Malley, Institutional Specialist Trifin Roule, Forensic Economist Jamie Thomson, Institutional Specialist Under the Biodiversity and Sustainable Forestry (BIOFOR) IQC Contract No. LAG-I-00-99-00013-00, Task Order 09 Submitted to: USAID/OTI and USAID/ANE/TS Submitted by: ARD, Inc. 159 Bank Street, Suite 300 Burlington, Vermont USA 05401 Tel: (802) 658-3890 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS............................................................................................................................................................ ii OVERVIEW OF CONFLICT TIMBER IN ASIA ................................................................................................1 INDONESIA CASE STUDY AND ANNEXES......................................................................................................6 BURMA CASE STUDY.......................................................................................................................................106 CAMBODIA CASE STUDY ...............................................................................................................................115 LAOS CASE STUDY ...........................................................................................................................................126 NEPAL/INDIA -

Seeking the State from the Margins: from Tidung Lands to Borderlands in Borneo

Seeking the state from the margins From Tidung Lands to borderlands in Borneo Nathan Bond ORCID ID: 0000-0002-8094-9173 A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. December 2020 School of Social and Political Sciences The University of Melbourne i Abstract Scholarship on the geographic margins of the state has long suggested that life in such spaces threatens national state-building by transgressing state order. Recently, however, scholars have begun to nuance this view by exploring how marginal peoples often embrace the nation and the state. In this thesis, I bridge these two approaches by exploring how borderland peoples, as exemplars of marginal peoples, seek the state from the margins. I explore this issue by presenting the first extended ethnography of the cross-border ethnic Tidung and neighbouring peoples in the Tidung Lands of northeast Borneo, complementing long-term fieldwork with research in Dutch and British archives. This region, lying at the interstices of Indonesian Kalimantan, Malaysian Sabah and the Southern Philippines, is an ideal site from which to study borderland dynamics and how people have come to seek the state. I analyse understandings of the state, and practical consequences of those understandings in the lives and thought of people in the Tidung Lands. I argue that people who imagine themselves as occupying a marginal place in the national order of things often seek to deepen, rather than resist, relations with the nation-states to which they are marginal. The core contribution of the thesis consists in drawing empirical and theoretical attention to the under-researched issue of seeking the state and thereby encouraging further inquiry into this issue. -

The Languages and Peoples of the Müller Mountains a Contribution to the Study of the Origins of Borneo’S Nomads and Their Languages

PB Wacana Vol. 16 No. 2 (2015) B. Sellato and A. SorienteWacana Vol., The 16 languages No. 2 (2015): and peoples 339–354 of the Müller Mountains 339 The languages and peoples of the Müller Mountains A contribution to the study of the origins of Borneo’s nomads and their languages Bernard Sellato and Antonia Soriente Abstract The Müller and northern Schwaner mountain ranges are home to a handful of tiny, isolated groups (Aoheng, Hovongan, Kereho, Semukung, Seputan), altogether totaling about 5,000 persons, which are believed to have been forest hunter-gatherers in a distant or recent past. Linguistic data were collected among these groups and other neighbouring groups between 1975 and 2010, leading to the delineation of two distinct clusters of languages of nomadic or formerly nomadic groups, which are called MSP (Müller-Schwaner Punan) and BBL (Bukat-Beketan-Lisum) clusters. These languages also display lexical affinity to the languages of various major Bornean settled farming groups (Kayan, Ot Danum). Following brief regional and particular historical sketches, their phonological systems and some key features are described and compared within the wider local linguistic setting, which is expected to contribute to an elucidation of the ultimate origins of these people and their languages. Keywords Borneo, nomads, hunter-gatherers, languages, history, Müller Mountains, Punan, Bukat, Aoheng. Bernard Sellato is a senior researcher at the Centre Asie du Sud-Est (CNRS/EHESS) in Paris. He has been working in and on Borneo since 1973, first as a geologist and then as an anthropologist. He is the author or editor of a dozen books about Borneo, a former director of the Institute for Research on Southeast Asia in Marseilles, France, and for ten years was the editor of the bilingual journal Moussons. -

Porosity of Sediment Mixtures with Different Grain Size Distribution

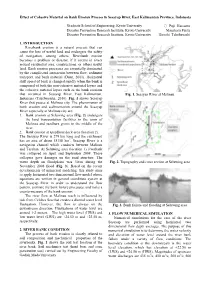

Effect of Cohesive Material on Bank Erosion Process in Sesayap River, East Kalimantan Province, Indonesia Graduate School of Engineering, Kyoto University 〇 Puji Harsanto Disaster Prevention Research Institute, Kyoto University Masaharu Fujita Disaster Prevention Research Institute, Kyoto University Hiroshi Takebayashi 1. INTRODUCTION Riverbank erosion is a natural process that can cause the loss of useful land and endangers the safety of navigation, among others. Riverbank erosion becomes a problem or disaster, if it occurs in rivers around residential area, constructions, or others useful land. Bank erosion processes are essentially dominated by the complicated interaction between flow, sediment transport, and bank material (Duan, 2001). Horizontal shift speed of bank is changed rapidly when the bank is composed of both the non-cohesive material layers and the cohesive material layers such as the bank erosions that occurred in Sesayap River, East Kalimantan, Fig. 1. Sesayap River at Malinau Indonesia (Takebayashi, 2010). Fig. 1 shows Sesayap River that passes at Malinau city. The phenomenon of bank erosion and sedimentation around the Sesayap River especially at Malinau city are: 1. Bank erosion at Seluwing area (Fig. 2) endangers the land transportation facilities in the town of Malinau and sandbars grows in the middle of the river, 2. Bank erosion at speedboat dock area (location 2). The Sesayap River is 279 km long and the catchment has an area of about 18158 km2. Sesayap River is a navigation channel which conducts between Malinau and Tarakan. At Seluwing area (location 1) riverbank was collapsed on April and September 2008. Those collapses gave damages on the road structure. -

Overview of Diplomatic Letters Listed Geographically by Region

Overview of Diplomatic Letters Listed Geographically by Region Region: Africa Egypt Location Place Alternative Name Cairo Saladin Citadel of Cairo Coordinates (lat/long):30.026608 31.259968 Accurate?Y Letters sent: 1 recieved:0 total: 1 Ethiopia Abyssinia Location Place Alternative Name Addis Ababa Coordinates (lat/long):8.988611 38.747932 Accurate?N Letters sent: 1 recieved:2 total: 3 Gondar Fasil Ghebbi Coordinates (lat/long):12.608048 37.469666 Accurate?Y Letters sent: 2 recieved:2 total: 4 South Africa Location Place Alternative Name Cape of Good Hope Castle of Good Hope Coordinates (lat/long):-33.925869 18.427623 Accurate?Y Letters sent: 9 recieved:0 total: 9 The castle was were most political exiles were kept Robben Island Robben Island Cape Town Coordinates (lat/long):-33.807607 18.371231 Accurate?Y Letters sent: 1 recieved:0 total: 1 Region: East Asia www.sejarah-nusantara.anri.go.id - ANRI TCF 2015 Page 1 of 44 Overview of Diplomatic Letters Listed Geographically by Region China Location Place Alternative Name Amoy Xiamen Coordinates (lat/long):24.479198 118.109207 Accurate?N Letters sent: 8 recieved:3 total: 11 Beijing Forbidden city Coordinates (lat/long):39.917906 116.397032 Accurate?Y Letters sent: 11 recieved:7 total: 18 Canton Guagnzhou Coordinates (lat/long):23.125598 113.227844 Accurate?N Letters sent: 7 recieved:4 total: 11 Chi Engling Coordinates (lat/long):23.646272 116.626946 Accurate?N Letters sent: 1 recieved:0 total: 1 Geodata unreliable Fuzhou Coordinates (lat/long):26.05016 119.31839 Accurate?N Letters sent: 32 -

Who Counts Most? Assessing Human Well-Being in Sustainable Forest Management

FA-CIFOR-Tool8Cover 6/15/99 8:25 AM Page 1 8 Who Counts Most? Assessing Human Well-Being The Grab Bag: Supplementary Methods for Assessing Human Well-Being Human Assessing for Methods Bag: Supplementary Grab The in Sustainable Forest Management Who Counts Most? Assessing Human Well-Being in Sustainable Forest Management presents a tool, ‘the Who Counts Matrix’, for differentiating ‘forest actors’, or people whose well-being and forest management are intimately intertwined, from other stakeholders. The authors argue for focusing formal attention on forest actors in efforts to develop sustainable forest management. They suggest seven dimensions by which forest actors can be differentiated from other stakeholders, and a simple scoring technique for use by formal managers in deter- mining whose well-being must form an integral part of sustainable forest management in a given locale. Building on the work carried out by the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) on criteria and indi- cators, they present three illustrative sets of stakeholders, from Indonesia, Côte d’Ivoire and the United States, and Who Counts Matrices from seven trials, in an appendix. 8The Criteria & Indicators Toolbox Series FA-CIFOR-Toolbox8-11.05 6/15/99 7:51 AM Page A2 ©1999 by Center for International Forestry Research Designed and Printed by AFTERHOURS +62 21 8306819 Photography Gorilla g. beringei by Tim Geer (WWF) Waterfall, Indonesia by Susan Archibald Kenyah hunter, Tanah Merah, Indonesia by Alain Compost Dendrobium sp. (Wild orchid) by Plinio Sist The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of Ms Rahayu Koesnadi to quality control of this manual.