Supplementary Materials the Thermodynamics of Selenium Minerals in Near-Surface Environments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Application of Near-Infrared and Mid-Infrared Spectroscopy to the Study of 3 Selected Tellurite Minerals: Xocomecatlite, Tlapallite and Rodalquilarite 4 5 Ray L

QUT Digital Repository: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/ Frost, Ray L. and Keeffe, Eloise C. and Reddy, B. Jagannadha (2009) An application of near-infrared and mid- infrared spectroscopy to the study of selected tellurite minerals: xocomecatlite, tlapallite and rodalquilarite. Transition Metal Chemistry, 34(1). pp. 23-32. © Copyright 2009 Springer 1 2 An application of near-infrared and mid-infrared spectroscopy to the study of 3 selected tellurite minerals: xocomecatlite, tlapallite and rodalquilarite 4 5 Ray L. Frost, • B. Jagannadha Reddy, Eloise C. Keeffe 6 7 Inorganic Materials Research Program, School of Physical and Chemical Sciences, 8 Queensland University of Technology, GPO Box 2434, Brisbane Queensland 4001, 9 Australia. 10 11 Abstract 12 Near-infrared and mid-infrared spectra of three tellurite minerals have been 13 investigated. The structure and spectral properties of two copper bearing 14 xocomecatlite and tlapallite are compared with an iron bearing rodalquilarite mineral. 15 Two prominent bands observed at 9855 and 9015 cm-1 are 16 2 2 2 2 2+ 17 assigned to B1g → B2g and B1g → A1g transitions of Cu ion in xocomecatlite. 18 19 The cause of spectral distortion is the result of many cations of Ca, Pb, Cu and Zn the 20 in tlapallite mineral structure. Rodalquilarite is characterised by ferric ion absorption 21 in the range 12300-8800 cm-1. 22 Three water vibrational overtones are observed in xocomecatlite at 7140, 7075 23 and 6935 cm-1 where as in tlapallite bands are shifted to low wavenumbers at 7135, 24 7080 and 6830 cm-1. The complexity of rodalquilarite spectrum increases with more 25 number of overlapping bands in the near-infrared. -

Washington State Minerals Checklist

Division of Geology and Earth Resources MS 47007; Olympia, WA 98504-7007 Washington State 360-902-1450; 360-902-1785 fax E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.dnr.wa.gov/geology Minerals Checklist Note: Mineral names in parentheses are the preferred species names. Compiled by Raymond Lasmanis o Acanthite o Arsenopalladinite o Bustamite o Clinohumite o Enstatite o Harmotome o Actinolite o Arsenopyrite o Bytownite o Clinoptilolite o Epidesmine (Stilbite) o Hastingsite o Adularia o Arsenosulvanite (Plagioclase) o Clinozoisite o Epidote o Hausmannite (Orthoclase) o Arsenpolybasite o Cairngorm (Quartz) o Cobaltite o Epistilbite o Hedenbergite o Aegirine o Astrophyllite o Calamine o Cochromite o Epsomite o Hedleyite o Aenigmatite o Atacamite (Hemimorphite) o Coffinite o Erionite o Hematite o Aeschynite o Atokite o Calaverite o Columbite o Erythrite o Hemimorphite o Agardite-Y o Augite o Calciohilairite (Ferrocolumbite) o Euchroite o Hercynite o Agate (Quartz) o Aurostibite o Calcite, see also o Conichalcite o Euxenite o Hessite o Aguilarite o Austinite Manganocalcite o Connellite o Euxenite-Y o Heulandite o Aktashite o Onyx o Copiapite o o Autunite o Fairchildite Hexahydrite o Alabandite o Caledonite o Copper o o Awaruite o Famatinite Hibschite o Albite o Cancrinite o Copper-zinc o o Axinite group o Fayalite Hillebrandite o Algodonite o Carnelian (Quartz) o Coquandite o o Azurite o Feldspar group Hisingerite o Allanite o Cassiterite o Cordierite o o Barite o Ferberite Hongshiite o Allanite-Ce o Catapleiite o Corrensite o o Bastnäsite -

Mineral Processing

Mineral Processing Foundations of theory and practice of minerallurgy 1st English edition JAN DRZYMALA, C. Eng., Ph.D., D.Sc. Member of the Polish Mineral Processing Society Wroclaw University of Technology 2007 Translation: J. Drzymala, A. Swatek Reviewer: A. Luszczkiewicz Published as supplied by the author ©Copyright by Jan Drzymala, Wroclaw 2007 Computer typesetting: Danuta Szyszka Cover design: Danuta Szyszka Cover photo: Sebastian Bożek Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej Wybrzeze Wyspianskiego 27 50-370 Wroclaw Any part of this publication can be used in any form by any means provided that the usage is acknowledged by the citation: Drzymala, J., Mineral Processing, Foundations of theory and practice of minerallurgy, Oficyna Wydawnicza PWr., 2007, www.ig.pwr.wroc.pl/minproc ISBN 978-83-7493-362-9 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................9 Part I Introduction to mineral processing .....................................................................13 1. From the Big Bang to mineral processing................................................................14 1.1. The formation of matter ...................................................................................14 1.2. Elementary particles.........................................................................................16 1.3. Molecules .........................................................................................................18 1.4. Solids................................................................................................................19 -

Tyrrellite (Cu, Co, Ni)3Se4 C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1

Tyrrellite (Cu, Co, Ni)3Se4 c 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1 Crystal Data: Cubic. Point Group: 4/m 32/m. Rounded grains and subhedral cubes. Physical Properties: Cleavage: {001}, poor. Fracture: Conchoidal. Tenacity: Brittle. Hardness = ∼3.5 VHN = 343–368 (100 g load). D(meas.) = n.d. D(calc.) = 6.6(2) Optical Properties: Opaque. Color: Pale bronze; pale brassy bronze in reflected light. Streak: Black. Luster: Metallic. R: (400) 41.8, (420) 42.6, (440) 43.5, (460) 44.4, (480) 45.0, (500) 45.5, (520) 45.9, (540) 46.3, (560) 46.5, (580) 46.8, (600) 47.0, (620) 47.3, (640) 47.5, (660) 47.6, (680) 47.8, (700) 48.0 Cell Data: Space Group: Fm3m. a = 10.005(4) Z = 8 X-ray Powder Pattern: Ato Bay, Canada. 1.769 (10), 2.501 (9), 2.886 (7), 3.016 (6), 1.926 (6), 5.780 (4), 3.537 (4) Chemistry: (1) (2) Cu 12.7 13.7 Co 17.7 11.6 Ni 6.9 12.0 Se 62.4 62.0 Total 99.7 99.3 (1) Beaverlodge district [sic; Goldfields district], Canada; by electron microprobe, corresponding to Cu1.01Co1.52Ni0.60Se4.00. (2) Hope’s Nose, England; by electron microprobe; corresponding to Cu1.10Ni1.04Co1.00Se4.00. Mineral Group: Linnaeite group. Occurrence: With other selenides, as the youngest hydrothermal replacements and open space fillings in sheared Precambrian rocks, which also contain uraninite deposits (Goldfields district, Canada). Association: Umangite, klockmannite, clausthalite, pyrite, hematite, chalcopyrite, chalcomenite (Ato Bay, Canada); berzelianite, eucairite, crookesite, ferroselite, bukovite, kruˇtaite, athabascaite, calcite, dolomite (Petrovice deposit, Czech Republic). -

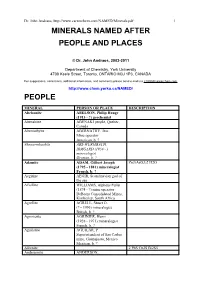

Minerals Named After Scientists

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Minerals.pdf 1 MINERALS NAMED AFTER PEOPLE AND PLACES © Dr. John Andraos, 2003-2011 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ PEOPLE MINERAL PERSON OR PLACE DESCRIPTION Abelsonite ABELSON, Philip Hauge (1913 - ?) geochemist Abenakiite ABENAKI people, Quebec, Canada Abernathyite ABERNATHY, Jess Mine operator American, b. ? Abswurmbachite ABS-WURMBACH, IRMGARD (1938 - ) mineralogist German, b. ? Adamite ADAM, Gilbert Joseph Zn3(AsO3)2 H2O (1795 - 1881) mineralogist French, b. ? Aegirine AEGIR, Scandinavian god of the sea Afwillite WILLIAMS, Alpheus Fuller (1874 - ?) mine operator DeBeers Consolidated Mines, Kimberley, South Africa Agrellite AGRELL, Stuart O. (? - 1996) mineralogist British, b. ? Agrinierite AGRINIER, Henri (1928 - 1971) mineralogist French, b. ? Aguilarite AGUILAR, P. Superintendent of San Carlos mine, Guanajuato, Mexico Mexican, b. ? Aikenite 2 PbS Cu2S Bi2S5 Andersonite ANDERSON, Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Minerals.pdf 2 Andradite ANDRADA e Silva, Jose B. Ca3Fe2(SiO4)3 de (? - 1838) geologist Brazilian, b. ? Arfvedsonite ARFVEDSON, Johann August (1792 - 1841) Swedish, b. Skagerholms- Bruk, Skaraborgs-Län, Sweden Arrhenite ARRHENIUS, Svante Silico-tantalate of Y, Ce, Zr, (1859 - 1927) Al, Fe, Ca, Be Swedish, b. Wijk, near Uppsala, Sweden Avogardrite AVOGADRO, Lorenzo KBF4, CsBF4 Romano Amedeo Carlo (1776 - 1856) Italian, b. Turin, Italy Babingtonite (Ca, Fe, Mn)SiO3 Fe2(SiO3)3 Becquerelite BECQUEREL, Antoine 4 UO3 7 H2O Henri César (1852 - 1908) French b. Paris, France Berzelianite BERZELIUS, Jöns Jakob Cu2Se (1779 - 1848) Swedish, b. -

Revision 2 of Ms. 5419 Page 1 Time's Arrow in the Trees of Life And

Revision 2 of Ms. 5419 Time’s Arrow in the Trees of Life and Minerals Peter J. Heaney1,* 1Dept. of Geosciences, Penn State University, University Park, PA 16802 *To whom correspondence should be addressed: [email protected] Page 1 Revision 2 of Ms. 5419 1 ABSTRACT 2 Charles Darwin analogized the diversification of species to a Tree of Life. 3 This metaphor aligns precisely with the taxonomic system that Linnaeus developed 4 a century earlier to classify living species, because an underlying mechanism – 5 natural selection – has driven the evolution of new organisms over vast timescales. 6 On the other hand, the efforts of Linnaeus to extend his “universal” organizing 7 system to minerals has been regarded as an epistemological misfire that was 8 properly abandoned by the late nineteenth century. 9 The mineral taxonomies proposed in the wake of Linnaeus can be 10 distinguished by their focus on external character (Werner), crystallography (Haüy), 11 or chemistry (Berzelius). This article appraises the competition among these 12 systems and posits that the chemistry-based Berzelian taxonomy, as embedded 13 within the widely adopted system of James Dwight Dana, ultimately triumphed 14 because it reflects Earth’s episodic but persistent progression with respect to 15 chemical differentiation. In this context, Hazen et al.’s (2008) pioneering work in 16 mineral evolution reveals that even the temporal character of the phylogenetic Tree 17 of Life is rooted within a Danan framework for ordering minerals. 18 19 Page 1 Revision 2 of Ms. 5419 20 INTRODUCTION 21 In an essay dedicated to the evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr, Stephen Jay 22 Gould (2000) expresses his indignation at the sheer luckiness of Carolus Linnaeus 23 (1707-1778; Fig. -

PALLADIUM and PLATINUM MINERALS from the SERRA PELADA Au–Pd–Pt DEPOSIT, CARAJÁS MINERAL PROVINCE, NORTHERN BRAZIL

1451 The Canadian Mineralogist Vol. 40, pp. 1451-1463 (2002) PALLADIUM AND PLATINUM MINERALS FROM THE SERRA PELADA Au–Pd–Pt DEPOSIT, CARAJÁS MINERAL PROVINCE, NORTHERN BRAZIL ALEXANDRE RAPHAEL CABRAL§ AND BERND LEHMANN Institut für Mineralogie und Mineralische Rohstoffe, Technische Universität Clausthal, Adolph-Roemer-Str. 2A, D–38678 Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany ROGERIO KWITKO-RIBEIRO Centro de Desenvolvimento Mineral, Companhia Vale do Rio Doce, BR 262/ km 296, 33030-970 Santa Luzia – MG, Brazil CARLOS HENRIQUE CRAVO COSTA Diretoria de Metais Nobres, Companhia Vale do Rio Doce, Caixa Postal 51, Serra dos Carajás, 68516-000 Parauabepas – PA, Brazil ABSTRACT The Serra Pelada garimpo (1980–1984) was the site of the most spectacular gold rush in recent history, but the mineralogy of the bonanza-style mineralization has not so far been documented in detail. Rediscovery of an early drill-core, recovered in 1982 from the near-surface lateritic portion of the garimpo area, has provided coarse-grained gold aggregates for this study. The centimeter-long aggregates of gold occur in powdery, earthy material. They exhibit a delicate arborescent fabric and are coated by goethite. Four compositional types of gold are recognized: palladian gold with an atomic ratio Au:Pd of 7:1 (“Au7Pd”), Hg- bearing palladian gold (Au–Pd–Hg), Pd-bearing gold with up to 3 wt.% Pd (Pd-poor gold) and pure gold. A number of platinum- group minerals (PGM) are included in, or attached to the surface of, palladian gold: “guanglinite”, Sb-bearing “guanglinite”, atheneite and isomertieite, including the noteworthy presence of Se-bearing PGM (Pd–Pt–Se, Pd–Se, Pd–Hg–Se and Pd–Bi–Se phases, and sudovikovite and palladseite). -

JOURNAL the Russell Society

JOURNAL OF The Russell Society Volume 20, 2017 www.russellsoc.org JOURNAL OF THE RUSSELL SOCIETY The journal of British Isles topographical mineralogy EDITOR Dr Malcolm Southwood 7 Campbell Court, Warrandyte, Victoria 3113, Australia. ([email protected]) JOURNAL MANAGER Frank Ince 78 Leconfield Road, Loughborough, Leicestershire, LE11 3SQ. EDITORIAL BOARD R.E. Bevins, Cardiff, U.K. M.T. Price, OUMNH, Oxford, U.K. R.S.W. Braithwaite, Manchester, U.K. M.S. Rumsey, NHM, London, U.K. A. Dyer, Hoddlesden, Darwen, U.K. R.E. Starkey, Bromsgrove, U.K. N.J. Elton, St Austell, U.K. P.A. Williams, Kingswood, Australia. I.R. Plimer, Kensington Gardens, S. Australia. Aims and Scope: The Journal publishes refereed articles by both amateur and professional mineralogists dealing with all aspects of mineralogy relating to the British Isles. Contributions are welcome from both members and non-members of the Russell Society. Notes for contributors can be found at the back of this issue, on the Society website (www.russellsoc.org) or obtained from the Editor or Journal Manager. Subscription rates: The Journal is free to members of the Russell Society. The non-member subscription rates for this volume are: UK £13 (including P&P) and Overseas £15 (including P&P). Enquiries should be made to the Journal Manager at the above address. Back numbers of the Journal may also be ordered through the Journal Manager. The Russell Society: named after the eminent amateur mineralogist Sir Arthur Russell (1878–1964), is a society of amateur and professional mineralogists which encourages the study, recording and conservation of mineralogical sites and material. -

1 Revision 1 Single-Crystal Elastic Properties of Minerals and Related

Revision 1 Single-Crystal Elastic Properties of Minerals and Related Materials with Cubic Symmetry Thomas S. Duffy Department of Geosciences Princeton University Abstract The single-crystal elastic moduli of minerals and related materials with cubic symmetry have been collected and evaluated. The compiled dataset covers measurements made over an approximately seventy year period and consists of 206 compositions. More than 80% of the database is comprised of silicates, oxides, and halides, and approximately 90% of the entries correspond to one of six crystal structures (garnet, rocksalt, spinel, perovskite, sphalerite, and fluorite). Primary data recorded are the composition of each material, its crystal structure, density, and the three independent nonzero adiabatic elastic moduli (C11, C12, and C44). From these, a variety of additional elastic and acoustic properties are calculated and compiled, including polycrystalline aggregate elastic properties, sound velocities, and anisotropy factors. The database is used to evaluate trends in cubic mineral elasticity through consideration of normalized elastic moduli (Blackman diagrams) and the Cauchy pressure. The elastic anisotropy and auxetic behavior of these materials are also examined. Compilations of single-crystal elastic moduli provide a useful tool for investigation structure-property relationships of minerals. 1 Introduction The elastic moduli are among the most fundamental and important properties of minerals (Anderson et al. 1968). They are central to understanding mechanical behavior and have applications across many disciplines of the geosciences. They control the stress-strain relationship under elastic loading and are relevant to understanding strength, hardness, brittle/ductile behavior, damage tolerance, and mechanical stability. Elastic moduli govern the propagation of elastic waves and hence are essential to the interpretation of seismic data, including seismic anisotropy in the crust and mantle (Bass et al. -

Raman Spectroscopic Study of the Tellurite Minerals: Carlfriesite and Spirof- fite

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Frost, Ray, Dickfos, Marilla,& Keeffe, Eloise (2009) Raman spectroscopic study of the tellurite minerals: Carlfriesite and spirof- fite. Spectrochimica Acta - Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 71(5), pp. 1663-1666. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/17256/ c Copyright 2009 Elsevier Reproduced in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2008.06.014 QUT Digital Repository: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/ Frost, Ray L. and Dickfos, Marilla J. and Keeffe, Eloise C. (2009) Raman spectroscopic study of the tellurite minerals : carlfriesite and spiroffite. Spectrochimica Acta Part A Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 71(5). pp. 1663-1666. © Copyright 2009 Elsevier Raman spectroscopic study of the tellurite minerals: carlfriesite and spiroffite Ray L. Frost, • Marilla J. Dickfos and Eloise C. Keeffe Inorganic Materials Research Program, School of Physical and Chemical Sciences, Queensland University of Technology, GPO Box 2434, Brisbane Queensland 4001, Australia. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract Raman spectroscopy has been used to study the tellurite minerals spiroffite 2+ and carlfriesite, which are minerals of formula type A2(X3O8) where A is Ca for the mineral carlfriesite and is Zn2+ and Mn2+ for the mineral spiroffite. -

Vibrational Spectroscopic Study of the Uranyl Selenite Mineral Derriksite

Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 117 (2014) 473–477 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/saa Vibrational spectroscopic study of the uranyl selenite mineral derriksite Cu4UO2(SeO3)2(OH)6ÁH2O ⇑ Ray L. Frost a, , JirˇíCˇejka b, Ricardo Scholz c, Andrés López a, Frederick L. Theiss a, Yunfei Xi a a School of Chemistry, Physics and Mechanical Engineering, Science and Engineering Faculty, Queensland University of Technology, GPO Box 2434, Brisbane Queensland 4001, Australia b National Museum, Václavské námeˇstí 68, CZ-115 79 Praha 1, Czech Republic c Geology Department, School of Mines, Federal University of Ouro Preto, Campus Morro do Cruzeiro, Ouro Preto, MG 35400-00, Brazil highlights graphical abstract We have studied the mineral derriksite Cu4UO2(SeO3)2(OH)6ÁH2O. A comparison was made with the other uranyl selenites. Namely demesmaekerite, marthozite, larisaite, haynesite and piretite. Approximate U–O bond lengths in uranyl and O–HÁÁÁO hydrogen bond lengths were calculated. article info abstract Article history: Raman spectrum of the mineral derriksite Cu4UO2(SeO3)2(OH)6ÁH2O was studied and complemented by Received 20 May 2013 the infrared spectrum of this mineral. Both spectra were interpreted and partly compared with the spec- Received in revised form 29 July 2013 tra of demesmaekerite, marthozite, larisaite, haynesite and piretite. Observed Raman and infrared bands Accepted 2 August 2013 were attributed to the (UO )2+, (SeO )2À, (OH)À and H O vibrations. The presence of symmetrically dis- Available online 22 August 2013 2 3 2 tinct hydrogen bonded molecule of water of crystallization and hydrogen bonded symmetrically distinct hydroxyl ions was inferred from the spectra in the derriksite unit cell. -

Chrisstanleyite Ag2pd3se4 C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1

Chrisstanleyite Ag2Pd3Se4 c 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1 Crystal Data: Monoclinic. Point Group: 2/m or 2. Anhedral crystals, to several hundred µm, aggregated in grains. Twinning: Fine polysynthetic and parquetlike, characteristic. Physical Properties: Tenacity: Slightly brittle. Hardness = ∼5 VHN = 371–421, 395 average (100 g load), D(meas.) = n.d. D(calc.) = 8.30 Optical Properties: Opaque. Color: Silvery gray. Streak: Black. Luster: Metallic. Optical Class: Biaxial. Pleochroism: Slight; pale buff to slightly gray-green buff. Anisotropism: Moderate; rose-brown, gray-green, pale bluish gray, dark steel-blue. Bireflectance: Weak to moderate. R1–R2: (400) 35.6–43.3, (420) 36.8–44.2, (440) 37.8–45.3, (460) 39.1–46.7, (480) 40.0–47.5, (500) 41.1–48.0, (520) 42.1–48.5, (540) 42.9–48.7, (560) 43.5–49.1, (580) 44.1–49.3, (600) 44.4–49.5, (620) 44.6–49.6, (640) 44.5–49.3, (660) 44.4–49.2, (680) 44.2–49.1, (700) 44.0–49.0 Cell Data: Space Group: P 21/m or P 21. a = 6.350(6) b = 10.387(4) c = 5.683(3) β = 114.90(5)◦ Z=2 X-ray Powder Pattern: Hope’s Nose, England. 2.742 (100), 1.956 (100), 2.688 (80), 2.868 (50b), 2.367 (50), 1.829 (30), 2.521 (20) Chemistry: (1) (2) (3) Pd 37.64 35.48 37.52 Pt 0.70 Hg 0.36 Ag 25.09 24.07 25.36 Cu 0.18 2.05 Se 36.39 38.50 37.12 Total 99.30 101.16 100.00 (1) Hope’s Nose, England; by electron microprobe, average of 26 analyses; corresponding to (Ag2.01Cu0.02)Σ=2.03Pd3.02Se3.95.