Revised Osborne Looking at Frankenstein Final Submission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015, Volume 8

V O L U M E 8 2015 D E PAUL UNIVERSITY Creating Knowledge THE LAS JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE SCHOLARSHIP CREATING KNOWLEDGE The LAS Journal of Undergraduate Scholarship 2015 EDITOR Warren C. Schultz ART JURORS Adam Schreiber, Coordinator Laura Kina Steve Harp COPY EDITORS Stephanie Klein Rachel Pomeroy Anastasia Sasewich TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 Foreword, by Interim Dean Lucy Rinehart, PhD STUDENT RESEARCH 8 S. Clelia Sweeney Probing the Public Wound: The Serial Killer Character in True- Crime Media (American Studies Program) 18 Claire Potter Key Progressions: An Examination of Current Student Perspectives of Music School (Department of Anthropology) 32 Jeff Gwizdalski Effect of the Affordable Care Act on Insurance Coverage for Young Adults (Department of Economics) 40 Sam Okrasinski “The Difference of Woman’s Destiny”: Female Friendships as the Element of Change in Jane Austen’s Emma (Department of English) 48 Anna Fechtor Les Musulmans LGBTQ en Europe Occidentale : une communauté non reconnue (French Program, Department of Modern Languages) 58 Marc Zaparaniuk Brazil: A Stadium All Its Own (Department of Geography) 68 Erin Clancy Authority in Stone: Forging the New Jerusalem in Ethiopia (Department of the History of Art and Architecture) 76 Kristin Masterson Emmett J. Scott’s “Official History” of the African-American Experience in World War One: Negotiating Race on the National and International Stage (Department of History) 84 Lizbeth Sanchez Heroes and Victims: The Strategic Mobilization of Mothers during the 1980s Contra War (Department -

Film Reviews

Page 117 FILM REVIEWS Year of the Remake: The Omen 666 and The Wicker Man Jenny McDonnell The current trend for remakes of 1970s horror movies continued throughout 2006, with the release on 6 June of John Moore’s The Omen 666 (a sceneforscene reconstruction of Richard Donner’s 1976 The Omen) and the release on 1 September of Neil LaBute’s The Wicker Man (a reimagining of Robin Hardy’s 1973 film of the same name). In addition, audiences were treated to remakes of The Hills Have Eyes, Black Christmas (due Christmas 2006) and When a Stranger Calls (a film that had previously been ‘remade’ as the opening sequence of Scream). Finally, there was Pulse, a remake of the Japanese film Kairo, and another addition to the body of remakes of nonEnglish language horror films such as The Ring, The Grudge and Dark Water. Unsurprisingly, this slew of remakes has raised eyebrows and questions alike about Hollywood’s apparent inability to produce innovative material. As the remakes have mounted in recent years, from Planet of the Apes to King Kong, the cries have grown ever louder: Hollywood, it would appear, has run out of fresh ideas and has contributed to its evergrowing bank balance by quarrying the classics. Amid these accusations of Hollywood’s imaginative and moral bankruptcy to commercial ends in tampering with the films on which generations of cinephiles have been reared, it can prove difficult to keep a level head when viewing films like The Omen 666 and The Wicker Man. -

John Collins Production Designer

John Collins Production Designer Credits include: BRASSIC Director: Rob Quinn, George Kane Comedy Drama Series Producer: Mags Conway Featuring: Joseph Gilgun, Michelle Keegan, Damien Molony Production Co: Calamity Films / Sky1 FEEL GOOD Director: Ally Pankiw Drama Series Producer: Kelly McGolpin Featuring: Mae Martin, Charlotte Richie, Sophie Thompson Production Co: Objective Fiction / Netflix THE BAY Directors: Robert Quinn, Lee Haven-Jones Crime Thriller Series Producers: Phil Leach, Margaret Conway, Alex Lamb Featuring: Morven Christie, Matthew McNulty, Louis Greatrex Production Co: Tall Story Pictures / ITV GIRLFRIENDS Directors: Kay Mellor, Dominic Leclerc Drama Series Producer: Josh Dynevor Featuring: Miranda Richardson, Phyllis Logan, Zoe Wanamaker Production Co: Rollem Productions / ITV LOVE, LIES AND RECORDS Directors: Dominic Leclerc, Cilla Ware Drama Producer: Yvonne Francas Featuring: Ashley Jensen, Katarina Cas, Kenny Doughty Production Co: Rollem Productions / BBC One LAST TANGO IN HALIFAX Director: Juliet May Drama Series Producer: Karen Lewis Featuring: Sarah Lancashire, Nicola Walker, Derek Jacobi Production Co: Red Production Company / Sky Living PARANOID Directors: Kenny Glenaan, John Duffy Detective Drama Series Producer: Tom Sherry Featuring: Indira Varma, Robert Glennister, Dino Fetscher Production Co: Red Production Company / ITV SILENT WITNESS Directors: Stuart Svassand Mystery Crime Drama Series Producer: Ceri Meryrick Featuring: Emilia Fox, Richard Lintern, David Caves Production Co: BBC One Creative Media Management -

Senate Extends Rights to UM Non-Students

Hurricane Blues Festival Program Inside Inside Special Suntan U? UM Blues Festival see page 4 tyqs fcw see Page 6 Vol. 48 No. 27 Friday, Feb. 16, 1973 284-4401 Senate Extends Rights To UM Non-Students By MICHAEL A. PARKER * * * And CHUCK GOMEZ Of The Hurricana Stall A move which could lead Carnival to more student participation on faculty decision-making boards was finalized Monday "Now administrative members can by Student Body Government Slated (SBG) senators. supply the Senate with needed knou> Senators voted in favor of giving a faculty member, an administrator and an ledge concerning any conflicting leg Thursday employe seats on the student Senate. The three representa islation with V.M. policy.** Called Largest tives would have regular Senate privileges including Of Its Kind voting rights and being able Poepelman to propose legislation. "Carni-Gras," a three-night "We felt they should have UM student -sponsored voting rights," said Senate carnival of games, conces speaker Kevin Poeppelman, sions, rides and educational "because there are often exhibits will open Thursday, many issues which would Feb. 22 on the intramural affect student relationships Presently students sit on during which some Senators tatives are expected to be se field and continue through with faculty, administration such boards as the Union complained that seating fac ated by the end of February. Saturday, Feb. 24. and employes." Board of Governors and ulty members would not in Dr. William Butler, vice Hours are 7 to 11:30 p.m., But Poeppelman told the Rathskeller Advisory Board, effect guarantee students but there is little campus president for student affairs, Thursday and Friday and 1 Hurricane that the move was could sit on faculty boards. -

King Lear − Learning Pack

King Lear − Learning Pack Contents About This Pack ................................................................1 Background Information ..................................................2 Teaching Information ........................................................3 Adaptation Details & Plot Synopsis..................................5 Find Out More...................................................................12 1 King Lear − Learning Pack About This learning pack supports the Donmar Warehouse production of King Lear, directed by Michael Grandage, which opened on 7th December 2010 in London. Our packs are designed to support viewing the recording on the National Theatre Collection. This pack provides links to the UK school curriculum and other productions in the Collection. It also has a plot synopsis with timecodes to allow you to jump to specific sections of the play. 1 King Lear − Learning Pack Background Information Recording Date – 3rd February, 2011 Location – Donmar Warehouse, London Age Recommendation – 12+ Cast Earl of Kent .................................................. Michael Hadley Early of Gloucester ...........................................Paul Jesson Edmund ...........................................................Alec Newman King Lear ......................................................... Derek Jacobi Goneril................................................................Gina McKee Regan ............................................................Justine Mitchell Cordelia .............................................Pippa -

(500) Days of Summer 2009

(500) Days of Summer 2009 (Sökarna) 1993 [Rec] 2007 ¡Que Viva Mexico! - Leve Mexiko 1979 <---> 1969 …And Justice for All - …och rättvisa åt alla 1979 …tick…tick…tick… - Sheriff i het stad 1970 10 - Blåst på konfekten 1979 10, 000 BC 2008 10 Rillington Place - Stryparen på Rillington Place 1971 101 Dalmatians - 101 dalmatiner 1996 12 Angry Men - 12 edsvurna män 1957 127 Hours 2010 13 Rue Madeleine 1947 1492: Conquest of Paradise - 1492 - Den stora upptäckten 1992 1900 - Novecento 1976 1941 - 1941 - ursäkta, var är Hollywood? 1979 2 Days in Paris - 2 dagar i Paris 2007 20 Million Miles to Earth - 20 miljoner mil till jorden 1957 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea - En världsomsegling under havet 1954 2001: A Space Odyssey - År 2001 - ett rymdäventyr 1968 2010 - Year We Make Contact, The - 2010 - året då vi får kontakt 1984 2012 2009 2046 2004 21 grams - 21 gram 2003 25th Hour 2002 28 Days Later - 28 dagar senare 2002 28 Weeks Later - 28 veckor senare 2007 3 Bad Men - 3 dåliga män 1926 3 Godfathers - Flykt genom öknen 1948 3 Idiots 2009 3 Men and a Baby - Tre män och en baby 1987 3:10 to Yuma 2007 3:10 to Yuma - 3:10 till Yuma 1957 300 2006 36th Chamber of Shaolin - Shaolin Master Killer - Shao Lin san shi liu fang 1978 39 Steps, The - De 39 stegen 1935 4 månader, 3 veckor och 2 dagar - 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days 2007 4: Rise of the Silver Surfer - Fantastiska fyran och silversurfaren 2007 42nd Street - 42:a gatan 1933 48 Hrs. -

Małgorzata Bugaj Panoptikum 2019, 21:81-94

Małgorzata Bugaj Panoptikum 2019, 21:81-94. https://doi.org/10.26881/pan.2019.21.05 Małgorzata Bugaj University of Edinburgh “We understand each other, my friend”. The freak show and Victorian medicine in The Elephant Man. Anxieties around the human body are one of the main preoccupations in the cinema of David Lynch. Lynch’s films are littered with grotesque corporealities (such as the monstrous baby in Eraserhead¸1977; or Baron Harkonnen in The Dune, 1984) and those of disabled or crippled characters (the protagonist in the short Amputee; 1973; the one-armed man in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, 1992). The bodies in his films are often presented as fragmented (literally, cut off from the whole, or figuratively, by using close-ups) or distorted in the eye of the camera (a technique used, for example, in Wild at Heart, 1990, or Inland Empire, 2006). The director frequently highlights human biology, particularly in bodies that are shown to lose control over their physiological functions (vomiting blood in The Alphabet, 1968, or urinating in Blue Velvet, 1986). This interest in characters defined primarily through their abnormal corporeal forms is readily apparent in Lynch’s second feature The Elephant Man (1980) centring on a man severely afflicted with a disfiguring disease1. 5IFGJMN MPPTFMZCBTFEPO4JS'SFEFSJDL5SFWFTNFNPJSThe Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences (1923), revolves around three characters inspired by real- life personas: John Merrick (the titular ‘Elephant Man’ Joseph Carey Merrick, %PDUPS5SFWFT UIFBGPSFNFOUJPOFE4JS'SFEFSJDL5SFWFT and Bytes (Tom Norman, 1860-1930). Accordingly, the story shifts between dif- 1 It is worth noting that the film was released in the wake of a cultural rediscovery of the John Merrick story nearly a century after his death. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

The Omen! BLOODY VALENTINES Exploitation Movie King John Dunning Interviewed!

THE DEVIL’S CHILD THE MAKinG OF THE Omen! BLOODY VALENTINES EXPLOitatiON MOvie KinG JOHN DunninG IntervieWED! MEDIEVAL MADNESS THE BLOOD On Satan’S SCARY MOVIE ClaW! ROUNDUP NEW DVDS and Blu-Rays DSD RevieWED! FREE! 06 Check out the teaser issue of CultTV Times... covering everything from NCIS to anime! Broadcast the news – the first full issue of Cult TV Times will be available to buy soon at Culttvtimes.com Follow us on : (@CultTVTimes) for the latest news and issue updates For subscription enquiries contact: [email protected] Introduction MACABRE MENU A WARM WELCOME TO THE 4 The omen 09 DVD LIBRARY 13 SUBS 14 SATAn’S CLAW DARKSIDe D I G I TA L 18 John DUnnIng contributing scripts it has to be good. I do think that Peter Capaldi is a fantastic choice for the new Doctor, especially if he uses the same language as he does in The Thick of It! Just got an early review disc in of the Blu-ray of Corruption, which is being released by Grindhouse USA in a region free edition. I have a bit of a vested interest in this one because I contributed liner notes and helped Grindhouse’s Bob Murawski find some of the interview subjects in the UK. It has taken some years to get this one in shops but the wait has been worthwhile because I can’t imagine how it could have been done better. I’ll be reviewing it at length in the next print issue, out in shops on October 24th. I really feel we’re on a roll with Dark Side at present. -

Mridula Sharma – Revisiting Bernard Rose's Frankenstein: Ugliness And

/ 95 Revisiting Bernard Rose’s Frankenstein: Ugliness and Exclusion MRIDULA SHARMA Abstract ary Shelley’s attempt to present what Ellen Moers labels as a ‘female gothic’ seems Mto endorse rigid notions of beauty: the transgression of socially approbated ideals of beauty leads to textual disposal in Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. Frankenstein’s desertion of the creation, for instance, testifies to the writer’s conscious effort to portray the beautiful and the ugly within the ambit of societal expectations of physical attractiveness. It is interesting to study the representation of the narrative in cinema because the transposition of Mary Shelley’s description into characters played by actors in reality is further influenced by the director’s perceptions of the textual reading as well as his presumptions of beauty. Bernard Rose’s film titled, Frankenstein (2015), appropriates the original text for public consumption: the monster’s initial corporeal beauty is transformed into supposed hideousness due to Frankenstein’s attempt to further augment his creation’s physical strength. The insertion of the monster’s Oedipal desire for Elizabeth supplements the investigation in the element of romance that is somewhat governed by the internalisation of conventional ideas of beauty. This paper endeavours to critique the contrast between the textual and cinematic portrayal of Frankenstein’s monster by examining the duality in the promotion of beauty in Rose’s film and contrasting it with the narrative space within Mary Shelley’s 1818 edition. Keywords: Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, Bernard Rose, Monster, Ugliness, Exclusion. Introduction The creations of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Rose’s Frankenstein have been referred to as the ‘monster’ in the article. -

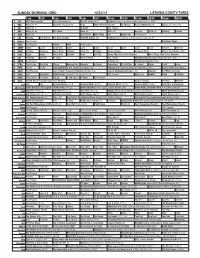

Sunday Morning Grid 12/21/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/21/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Kansas City Chiefs at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Young Men Big Dreams On Money Access Hollywood (N) Skiing U.S. Grand Prix. 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. Outback Explore 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Atlanta Falcons at New Orleans Saints. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Christmas Angel 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Alsace-Hubert Heirloom Meals Man in the Kitchen (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Christmas Twister (2012) Casper Van Dien. (PG) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia 101 Dalmatians ›› (1996) Glenn Close. -

Catrin Meredydd Production Designer

Catrin Meredydd Production Designer Winner of BAFTA Cymru award for Best Production Design 2017 for Damilola, Our Loved Boy. Winner of BAFTA Cymru award for Best Production Design 2019 for Black Mirror: Bandersnatch. Agents Madeleine Pudney Assistant 020 3214 0999 Eliza McWilliams [email protected] 020 3214 0999 Daniela Manunza Assistant [email protected] Lizzie Quinn [email protected] + 44 (0) 203 214 0911 Credits In Development Production Company Notes CHASING AGENT Great Point Media / Rabbit Track Dirs: Declan Lawn & Adam FREEGARD Pictures / The Development Partnership Patterson 2021 Prods: Michael Bronner, Kitty Kaletsky & Robert Taylor SOULMATES 2 AMC / Amazon Postponed 2020 Film Production Company Notes United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] MRS LOWRY AND SON Genesius Pictures Dir: Adrian Noble Prod: Debbie Gray Period Drama 1930's Starring Vanessa Redgrave & Timothy 2019 Spall IBOY Wigwam Films/ Pretty Dir: Adam Randall Pictures Prods: Lucan Toh, Oliver Roskill, Emily Leo, Contemporary Gail Mutrux 2016 With Bill Milner, Rory Kinnear, Miranda Richardson, Maisie Williams BELIEVE Bill and Ben Productions Dir: David Scheinmann Prods: Manuela Noble, Ben Timlett 1950's/1980's With Brian Cox, Toby Stephens, Natascha 2013 McElhone Television Production Company Notes CURSED Netflix Dirs: Jon East, Zetna Fuentes, Daniel Nettheim and Sarah O'Gorman 10 x 60 Medieval Drama Showrunners: Tom Wheeler and Frank Miller 2019