Małgorzata Bugaj Panoptikum 2019, 21:81-94

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Historical Articulation of the Disabled Body in the Archive

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons English Theses & Dissertations English Spring 2019 Speaking for the Grotesques: The Historical Articulation of the Disabled Body in the Archive Violet Marie Strawderman Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Disability Studies Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Strawderman, Violet M.. "Speaking for the Grotesques: The Historical Articulation of the Disabled Body in the Archive" (2019). Master of Arts (MA), thesis, English, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/ 3qzd-0r71 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds/80 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the English at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPEAKING FOR THE GROTESQUES: THE HISTORICAL ARTICULATION OF THE DISABLED BODY IN THE ARCHIVE by Violet Marie Strawderman B.A. May 2016, Old Dominion University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS ENGLISH OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY May 2019 Approved by: Drew Lopenzina (Director) Ruth Osorio (Member) Elizabeth J. Vincelette (Member) ABSTRACT SPEAKING FOR THE GROTESQUES: THE HISTORICAL ARTICULATION OF THE DISABLED BODY IN THE ARCHIVE Violet Marie Strawderman Old Dominion University, 2019 Director: Dr. Drew Lopenzina This project examines the ways in which the disabled body is constructed and produced in larger society, via the creation of and interaction with (and through) the archive. -

Cassette Books, CMLS,P.O

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 319 210 EC 230 900 TITLE Cassette ,looks. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. PUB DATE 8E) NOTE 422p. AVAILABLE FROMCassette Books, CMLS,P.O. Box 9150, M(tabourne, FL 32902-9150. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) --- Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adults; *Audiotape Recordings; *Blindness; Books; *Physical Disabilities; Secondary Education; *Talking Books ABSTRACT This catalog lists cassette books produced by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped during 1989. Books are listed alphabetically within subject categories ander nonfiction and fiction headings. Nonfiction categories include: animals and wildlife, the arts, bestsellers, biography, blindness and physical handicaps, business andeconomics, career and job training, communication arts, consumerism, cooking and food, crime, diet and nutrition, education, government and politics, hobbies, humor, journalism and the media, literature, marriage and family, medicine and health, music, occult, philosophy, poetry, psychology, religion and inspiration, science and technology, social science, space, sports and recreation, stage and screen, traveland adventure, United States history, war, the West, women, and world history. Fiction categories includer adventure, bestsellers, classics, contemporary fiction, detective and mystery, espionage, family, fantasy, gothic, historical fiction, -

Victorian Blockbuster Bodies and the Freakish Pleasure of Looking

Nineteenth-Century Contexts An Interdisciplinary Journal ISSN: 0890-5495 (Print) 1477-2663 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gncc20 Victorian Blockbuster Bodies and the Freakish Pleasure of Looking Sharrona Pearl To cite this article: Sharrona Pearl (2016) Victorian Blockbuster Bodies and the Freakish Pleasure of Looking, Nineteenth-Century Contexts, 38:2, 93-106, DOI: 10.1080/08905495.2016.1135366 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08905495.2016.1135366 Published online: 12 Feb 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 135 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gncc20 Download by: [University of Pennsylvania] Date: 20 October 2016, At: 06:50 NINETEENTH-CENTURY CONTEXTS, 2016 VOL. 38, NO. 2, 93–106 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08905495.2016.1135366 Victorian Blockbuster Bodies and the Freakish Pleasure of Looking Sharrona Pearl The Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA Introduction Let us think together about pleasure. Is everything that we enjoy pleasurable, and can there be plea- sure in that which we do not enjoy? And, poignantly, when and why do we feel the need to apologize for pleasure? Pleasure has been coupled with a variety of visual practices and experiences, and, at its extremes, has been tarred with the judgmental brush of fetish.1 There are some things, it seems, that are not okay to look at. Or, more specifically, there are some things that are not okay to enjoy looking at. -

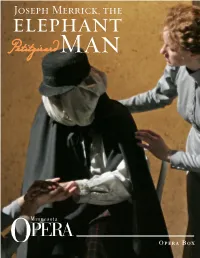

Joseph Merrick, the Elephant Man Opera Box Lesson Plan Unit Overview with Related Academic Standards

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis . .22 Laurent Petitgirard – a biography ............................25 Background Notes . .27 History of Opera ........................................31 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .42 The Standard Repertory ...................................46 Elements of Opera .......................................47 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................51 Glossary of Musical Terms .................................57 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .60 Acknowledgements . .62 GIACOMO PUCCINI NOVEMBER 5 – 13, 2005 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART MARCH 4 – 12, 2006 mnopera.org SAVERIO MERCADANTE APRIL 8 – 15, 2006 LAURENT PETITGIRARD MAY 13 – 21, 2006 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 620 North First Street, Minneapolis, MN 55401 Kevin Ramach, PRESIDENT AND GENERAL DIRECTOR Dale Johnson, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear Educator, Thank you for using a Minnesota Opera Opera Box. This collection of material has been designed to help any educator to teach students about the beauty of opera. This collection of material includes audio and video recordings, scores, reference books and a Teacher’s Guide. The Teacher’s Guide includes Lesson Plans that have been designed around the materials found in the box and other easily obtained items. In addition, Lesson Plans have been aligned with State and National Standards. See the Unit Overview for a detailed explanation. Before returning the box, please fill out the Evaluation Form at the end of the Teacher’s Guide. As this project is new, your feedback is imperative. Comments and ideas from you – the educators who actually use it – will help shape the content for future boxes. In addition, you are encouraged to include any original lesson plans. -

PRESS RELEASE BERNARD POMERANCE, Author of The

PRESS RELEASE IMAGE CAN BE DOWNLOADED HERE BERNARD POMERANCE, author of The Elephant Man dies in New Mexico. Bernard Pomerance, the American playwright and poet who wrote the Tony Award winning play The Elephant Man, died at his home in Galisteo, New Mexico on the morning of Saturday, August 26, 2017. The death was confirmed by his long time agent Alan Brodie. The cause of death was complications from cancer. Bernard Kline Pomerance was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1940. He studied at the University of Chicago before moving to London in 1968. His first play, High in Vietnam, Hot Damn, was directed by Roland Rees with whom he went on (together with David Aukin) to form the theatre company Foco Novo in 1972 which was at the forefront of British Theatre in the 1970s and 80s. Mr. Pomerance first wrote The Elephant Man for Foco Novo premiering at Hampstead Theatre in 1977 and the play went on to become one of the most successful plays to ever come out of London theatre and was produced around the world. The play opened on Broadway at the Booth Theatre in 1979 and it went on to play 916 performances and won the Tony Award for Best Play. The leading role of John Merrick has been played by numerous leading actors over the years including David Schofield (who originated the role at Hampstead and in the 1980 production at the National Theatre) Philip Anglim, David Bowie, Billy Crudup and most recently Bradley Cooper who starred in the play’s last revival in 2015 at the Booth Theatre in New York and at the Theatre Royal Haymarket in London the next year. -

Working Paper: Understanding the Multiple Roles of the Emergency Manager Through Pomerance’S the Elephant Man

1 Working Paper: Understanding the Multiple Roles of the Emergency Manager through Pomerance’s The Elephant Man Cindy L Pressley ([email protected]) and Michael Noel ([email protected]) Stephen F Austin State University *Cindy L Pressley is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Government at Stephen F Austin State University. Michael Noel is a graduate student in the Master’s of Public Administration Program at Stephen F Austin State University. 2 Working Paper: Understanding the Multiple Roles of the Emergency Manager through Pomerance’s The Elephant Man BISHOP: I find my sessions with him utterly moving, Mr. Treves. He struggles so. I suggested he might like to be confirmed; he leaped at it like a man lost in a desert to an oasis. TREVES: He is very excited to do what others do if he thinks it is what others do. BISHOP: Do you cast doubt, sir, on his faith? TREVES: No, sir, I do not. Yet he makes all of us think he is deeply like ourselves. And yet we’re not like each other. I conclude that we have polished him like a mirror, and shout hallelujah when he reflects us to the inch. I have grown sorry for it. -p. 64, The Elephant Man This paper first began to develop out of a story told by William Alexander Percy in his autobiography Lanterns on the Levee: Recollections of a Planter’s Son originally published in 1941. One story he relates is that of the deadly 1927 Mississippi flood that killed close to 1,000 people. -

Handbills 178T

Handbills 178T 178T1- John Bramwell Taylor Collection 178T2-Circus Modern 178T3-Fairs Early 178T4-Steam Fairs (including Harry Lee) 178T5-Wall of Death (including Billy Bellhouse and Alma Skinner Collections) 178T6-Circus (early travelling and permanent) 178T7- George Dawson Collection 178T8-Shufflebottom Family Collection 178T9-Hamilton Kaye Collection 178T10-Fairs (modern, including David Fitzroy Collection) 178T11-Rail Excursions 178T12-New Variety and Theatre 178T13-Marisa Carnesky Collection 178T14-Variety and Music Hall 178T15-Pleasure Gardens 178T16-Waxworks (travelling and fixed) 178T17-Early Film and Cinema (travelling and fixed) 178T18- Travelling entertainments 178T19-Optical shows (travelling and fixed) 178T20-Panoramas (travelling and fixed) 178T21-Menageries/performing animals (travelling and fixed) 178T22-Oddities and Curios (travelling and fixed) 178T23- Fixed entertainment venues 178T24-Wild West 178T25-Boxing 178T26-Lulu Adams Collection 178T27-Cyril Critchlow Collection –see separate finding aid 178T28- Magic and Illusion 178T29 – Hal Denver Collection 178T30 – Charles Taylor Collection 178T31-Fred Holmes Collection (Jasper Redfern) 178T32-Hodson Family Collection 178T33-Gerry Cottle Collection 178T34 - Ben Jackson Collection 178T35 – Family La Bonche Project Collection 178T36 – Paul Braithwaite Collection 178T37 – Chris Russell Collection 178T38 – Exhibitions 178T39 – David Robinson (Not yet available) 178T40 – Circus Friends Association Collection (Not yet available) 178T41 – O’Beirne Collection 178T42 – Smart Family -

THE ELEPHANT MAN by Bernard Pomerance

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Publicity Contact: Email: [email protected] “ELOQUENTLY WRITTEN – DEEPLY MOVING” Thursday Night Theater Club Presents A Classic True-life Tale in THE ELEPHANT MAN By Bernard Pomerance Opening March 21 at El Portal Theatre Press Review Night: March 22, 2019 LOS ANGELES (January 28, 2019) – Thursday Night Theatre Club is proud to present a classic true-life tale and heart wrenching story that depicts the best and the worst of humanity. The Elephant Man is an eloquently written play by Bernard Pomerance, and is being directed by Robyn Cohen at The Historic El Portal Theatre. Running March 21 – 23 and April 3 – 14, 2019. Tickets: www.ElPortalTheatre.com ABOUT THE SHOW Taking place in Victorian England 1884, this gripping drama is based on the real life events of Joseph Carey Merrick. The Elephant Man is the story of a 19th century Englishman who has an unprecedented physical deformation. As a victim of a rare skin and bone disease called Proteus Syndrome, Merrick eventually becomes the star of a traveling freak show circuit. When the renowned Dr. Frederick Treves takes Merrick under his care, he is astonished by the young man’s brilliant mind, unshakable faith, and passionate desire for love, acceptance and romance. Merrick‘s astonishing and moving story is the basis for this Tony award winning play. Part of that story includes Merrick’s acquaintance with a beautiful actress, Mrs. Kendal. She becomes entranced by Merrick‘s pure and genuine soul. As a complex friendship between the three main characters blossoms, Dr. Treves and Mrs. Kendall struggle to protect Merrick from the severity of his worsening condition, as well as from a world of opportunism, exploitation that make achieving a normal life seem all but impossible. -

Download Data When the Moon Is Bright

Why buy a single stock when you can invest in the entire sector? BENEFITS INCLUDE: - S&P 500 Components - The all-day tradability of stocks CHICAGO PILE-1 … - The diversifi cation of mutual funds - Liquidity - Total transparency - Expenses - 0.14%** INQUIRY … BELLOW’S PAPERS … FANTASTIC BEASTS … MARTIN LUTHER … FIRST AMENDMENT SCHOLAR HEALTH CARE Sector SPDR ETF Top 10 Holdings* Company Name Symbol Weight XLV Johnson & Johnson JNJ 11.45% Pfi zer PFE 6.50% Unitedhealth UNH 6.21% Merck MRK 5.61% Amgen AMGN 4.20% AbbVie ABBV 3.85% Medtronic MDT 3.56% Gilead Sciences GILD 3.51% *Components and weightings Celgene CELG 3.48% as of 8/31/17. Please see website for daily updates. Bristol-Myers Squibb BMY 3.22% Holdings subject to change. Visit www.sectorspdrs.com or call 1-866-SECTOR-ETF An investor should consider investment objectives, risks, charges and expenses carefully before investing. To obtain a prospectus, which contains this and other information, call 1-866-SECTOR-ETF or visit www.sectorspdrs.com. Read the prospectus carefully before investing. The S&P 500, SPDRs®, and Select Sector SPDRs® are registered trademarks of Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC. and have been licensed for use. The stocks included in each Select Sector Index were selected by the compilation agent. Their composition and weighting can be expected to di er to that in any similar indexes that are published by S&P. The S&P 500 Index is an unmanaged index of 500 common stocks that is generally considered representative of the U.S. stock market. -

Author List for Advertisers This Is the Master Set of Authors Currently Available to Be Used As Target Values for Your Ads on Goodreads

Author List for Advertisers This is the master set of authors currently available to be used as target values for your ads on Goodreads. Use CTRL-F to search for your author by name. Please work with your Account Manager to ensure that your campaign has a sufficient set of targets to achieve desired reach. Contact your account manager, or [email protected] with any questions. 'Aidh bin Abdullah Al-Qarni A.G. Lafley A.O. Peart 029 (Oniku) A.G. Riddle A.O. Scott 37 Signals A.H. Tammsaare A.P.J. Abdul Kalam 50 Cent A.H.T. Levi A.R. Braunmuller A&E Kirk A.J. Church A.R. Kahler A. American A.J. Rose A.R. Morlan A. Elizabeth Delany A.J. Thomas A.R. Torre A. Igoni Barrett A.J. Aalto A.R. Von A. Lee Martinez A.J. Ayer A.R. Winters A. Manette Ansay A.J. Banner A.R. Wise A. Meredith Walters A.J. Bennett A.S. Byatt A. Merritt A.J. Betts A.S. King A. Michael Matin A.J. Butcher A.S. Oren A. Roger Merrill A.J. Carella A.S.A. Harrison A. Scott Berg A.J. Cronin A.T. Hatto A. Walton Litz A.J. Downey A.V. Miller A. Zavarelli A.J. Harmon A.W. Exley A.A. Aguirre A.J. Hartley A.W. Hartoin A.A. Attanasio A.J. Jacobs A.W. Tozer A.A. Milne A.J. Jarrett A.W. Wheen A.A. Navis A.J. Krailsheimer Aaron Alexovich A.B. Guthrie Jr. A.J. -

2015 Tony Award® Nominations Best Play Best Best Best Featured Best Actor Actress Actress Director Steven Geneva Sarah Moritz Von Boyer Carr Stiles Stuelpnagel

06.04.15 • BACKSTAGE.COM 2015 TONY AWARD® NOMINATIONS BEST PLAY BEST BEST BEST FEATURED BEST ACTOR ACTRESS ACTRESS DIRECTOR STEVEN GENEVA SARAH MORITZ VON BOYER CARR STILES STUELPNAGEL THE MOST-NOMINATED Photo by Joan Marcus coverwrap V02.indd 1 6/2/15 4:21 PM TONY AWARD NOMINATION BEST ACTOR-STEVEN BOYER “THE SENSATIONAL STEVEN BOYER’s performance as Jason is tender and touching, his performance as Tyrone outlandish and hilarious; put them together and you have that rarely seen (although often hailed) acting achievement: A TRUE TOUR DE FORCE.” THE MOST-NOMINATED TONY AWARD NOMINATION BEST ACTRESS- GENEVA CARR “THE WONDERFUL GENEVA CARR plays a character on the dangerous edge of desperation throughout, but she keeps Margery sympathetic, giving her fragility a soft sexiness that makes her believable as an object of desire to both the lonely pastor and the teenage delinquent.” Photos by Joan Marcus Untitled-3 1 6/1/15 12:13 PM 06.04.15 • BACKSTAGE.COM 0604 COVER V02.indd 1 6/2/15 11:43 AM BEFORE THEY WERE STARS, THEY WERE STUDENTS. Christian Borle, Carnegie Mellon Alumnus, 2015 Tony Awards Stephen Schwartz, Carnegie Mellon nominee for Best Performance Alumnus, 2015 Isabelle Stevenson by a Featured Actor in a Musical Award Recipient THE TONY AWARDS® AND CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY ARE PROUD TO PRESENT THE INAUGURAL EXCELLENCE IN THEATRE EDUCATION AWARD. TUNE IN TO THE 69TH ANNUAL TONY AWARDS ON CBS, SUNDAY, JUNE 7. CMU.EDU/TONY-AWARDS • #CMUtonys Untitled-18 1 5/26/15 4:11 PM CONTENTS vol. 56, no. 23 | 06.04.15 COVER STORY page 18 NEWS 8 On the scene at the 2015 Heller Awards YOUR 2015 9 MN Acting Studio’s new workshops 10 Six missing Tony Award categories TONY- ADVICE 13 THE WORKING ACTOR Bypassing the gatekeepers NOMINATED 14 SECRET AGENT MAN Who’s on your team? 16 #IGOTCAST ACTORS Courtney Jensen And why their performances reigned FEATURES supreme on 2014–15 Broadway stages 6 BACKSTAGE 5 WITH… Debi Mazar 12 INSIDE JOB Gerald Griffith, VoiceoverCity 14 SPOTLIGHT ON… Ty Simpkins 16 NOW STREAMING “L.A. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Peter Blair, Executive Director December 15, 2010 Ph

BoHo Theatre 2437 W Farragut Ave #3B, Chicago, IL 60625 773-791-2393 www.BoHoTheatre.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Peter Blair, Executive Director December 15, 2010 Ph. 860-833-1107 (not for publication) [email protected] BOHO THEATRE CONTINUES ITS SEASON AT THEATER WIT WITH THE ELEPHANT MAN CHICAGO— BoHo Theatre presents Bernard Pomerance’s The Elephant Man, winner of the Tony, Drama Desk, and New York Drama Critics’ Circle Awards for best play, running January 7 through February 6, 2011 at Theater Wit, 1229 W Belmont Avenue. The Elephant Man is directed by June Eubanks. ―He makes all of us think he is deeply like ourselves. And yet we’re not like each other. I conclude that we have polished him like a mirror, and shout hallelujah when he reflects us to the inch. I have grown sorry for it.‖ –The Elephant Man In Victorian London, Dr. Frederick Treves discovers the misshapen, stunted John Merrick in a freak show and rescues him in order to study his peculiar deformity. But Merrick turns out to be unusually bright and articulate, and soon becomes the toast of high society. His new popularity, however, only increases his frustration and isolation created by his deformed exterior. Has he simply traded one freak show for another? BoHo brings this thrillingly intimate story to life with a boldly physical staging that highlights the layers of self, intentional and not, that separate us all from each other. LISTING INFORMATION The Elephant Man By Bernard Pomerance Directed by June Eubanks Cast: Thad Anzur, Zach Bloomfield, Jill Connolly, Cameron Feagin, Michael Kingston, Michael Mercier, Steve O'Connell, Laura Rook, Stephanie Sullivan, and Mike Tepeli as John Merrick.