Joseph Merrick, the Elephant Man Opera Box Lesson Plan Unit Overview with Related Academic Standards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Casting Announced for Asolo Rep's MORNING AFTER GRACE Directed by Peter Amster; Production Runs Jan

MORNING AFTER GRACE Page 1 of 6 ***For Immediate Release*** December 19, 2017 Casting Announced for Asolo Rep's MORNING AFTER GRACE Directed by Peter Amster; Production runs Jan. 17 - March 4 (SARASOTA, December 19, 2017) — Asolo Rep continues its repertory season with MORNING AFTER GRACE, a poignant comedy about new love for the older set. Penned by playwright Carey Crim, a fresh voice for the American stage, and directed by Asolo Rep Associate Artist Peter Amster (Asolo Rep: Born Yesterday, Living on Love, The Matchmaker, and more), MORNING AFTER GRACE previews January 17 and 18, opens January 19 and runs in rotating repertory through March 4 in the Mertz Theatre, located in the FSU Center for the Performing Arts. The morning after a funeral, Abigail and Angus awake from a whirlwind, booze-fueled one- night-stand on Angus' couch. And so begins this unconventional comedy, set in a not-so- distant Florida retirement community. As Abigail and Angus uncover the meaning of their hook-up and future, Abigail's neighbor Ollie, a retired baseball pro, struggles to find a way to make sense of his past and the secret he's hidden for decades. Hilarious and heart- warming, MORNING AFTER GRACE reminds us that it is never too late to rediscover love, and yourself, again. -more- MORNING AFTER GRACE Page 2 of 6 MORNING AFTER GRACE premiered at the Purple Rose Theatre Company in 2016. Asolo Rep's production of the play has provided an exciting opportunity for Carey Crim to be in rehearsals and work with Peter Amster to hone and fine tune the play even further. -

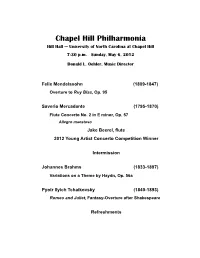

Concert Program

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Hill Hall — University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 6, 2012 Donald L. Oehler, Music Director Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Overture to Ruy Blas, Op. 95 Saverio Mercadante (1795-1870) Flute Concerto No. 2 in E minor, Op. 57 Allegro maestoso Jake Beerel, flute 2012 Young Artist Concerto Competition Winner Intermission Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56a Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) Romeo and Juliet, Fantasy-Overture after Shakespeare Refreshments Inspirations William Shakespeare conveyed the overwhelming impact of Julius Caesar in imperial Rome: “Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world like a Colussus.” So might 19th century composers have viewed the figure of Ludwig van Beethoven. With his Symphony No. 3, known as Eroica, composed in 1803, Beethoven radically altered the evolution of symphonic music. The work was inspired by Napoléon Bonaparte’s republican ideals while rejecting that ‘hero’s’ assumption of an imperial mantle. Beethoven broke precedent by employing his art “as a vehicle to convey beliefs,” expanding beyond compositional technique to add the “dimension of meaning and interpretation. All the more remarkable…the high priest of absolute music, effected this change.” (composer W.A. DeWitt) Beethoven, in a word, brought Romanticism to the concert hall, “replac[ing] the Enlightenment cult of reason with a cult of instinct, passion, and the creative genius as virtual demigod. The Romantics seized upon Beethoven’s emotionalism, his sense of the individual as hero.” (composer/writer Jan Swafford) The expression of this new sensibility took many forms, ranging from intensified expression within classical forms, exemplified by Felix Mendelssohn or Johannes Brahms, to the unbridled fervor of Piyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, the revolutionary virtuosity and structural innovations of Franz Liszt, the hallucinatory visions of Hector Berlioz, and the megalomania of Richard Wagner. -

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

Eric Mandat's Chips Off the Ol' Block

California State University, Northridge FLUTTER, SWING, AND SQUAWK: ERIC MANDAT’S CHIPS OFF THE OL’ BLOCK A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Music in Performance By Nicole Irene Moran December 2012 Thesis of Nicole Irene Moran is approved: ___________________________________ ___________________ Dr. Lawrence Stoffel Date ___________________________________ ___________________ Professor Mary Schliff Date ___________________________________ ___________________ Dr. Julia Heinen, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Dedicated to: Robert Paul Moran (12/13/39- 8/6/11) iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ii Dedication iii Abstract v FLUTTER, SWING, AND SQUAWK: ERIC MANDAT’S CHIPS OFF THE OL’ BLOCK 1 Recital Program 26 Bibliography 27 iv ABSTRACT FLUTTER, SWING, AND SQUAWK: ERIC MANDAT’S CHIPS OFF THE OL’ BLOCK By Nicole Irene Moran Master of Music in Performance The bass clarinet first appeared in the music world as a supportive instrument in orchestras, wind ensembles and military bands, but thanks to Giuseppe Saverio Raffaele Mercadante’s opera Emma d'Antiochia (1834), the bass clarinet began to embody the role of a soloist. Important passages in orchestral works such as Strauss’ Don Quixote (1898) and Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring (1913) further advanced the perception of the bass clarinet as a solo instrument, and beginning in the 1970’s, composers such as Harry Sparnaay and Brian Ferneyhough began writing solo works for unaccompanied bass clarinet. In the twenty-first century, clarinet virtuoso and composer Eric Mandat experiments with the capabilities of the bass clarinet in his piece Chips Off the Ol’ Block, utilizing enormous registral leaps, techniques such as multiphonics and quarter-tone fingerings, as well as incorporating jazz-inspired rhythms into the music. -

A Bestiary of the Arts

LA LETTRE ACADEMIE DES BEAUX-ARTS A BESTIARY OF THE ARTS 89 Issue 89 Spring 2019 Editorial • page 2 News: Annual Public Meeting of the Five Academies News: Installations under the Coupole: Adrien Goetz and Jacques Perrin News: Formal Session of the Académie des beaux-arts • pages 3 to 7 Editorial The magnificent Exhibition: “Oriental Visions: Cynocephalus adorning the cover of this edition of From Dreams into Light” La Lettre emanates a feeling of peaceful strength Musée Marmottan Monet true to the personality of its author, Pierre-Yves • pages 8 and 9 File: Trémois, the oldest member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts after being elected to Paul Lemangy’s “A bestiary of the arts” seat on 8 February 1978. • pages 10 to 34 Through the insatiable curiosity and astounding energy that he brings to the table at the age of News: “Concerts for a seat” ninety-eight, Pierre-Yves Trémois shows us Elections: Jean-Michel Othoniel, the extent to which artistic creation can be Marc Barani, Bernard Desmoulin, regenerative, especially when it is not seeking to conform to any passing trend. News: The Cabinet des estampes de la In May 2017 we elected forty-three year-old composer Bruno Mantovani to Jean bibliothèque de l’Institut Prodromidès’ seat. Tribute: Jean Cortot Watching the two passionately converse about art, we realized that the half • pages 35 to 37 century separating them was of no importance. The Académie des Beaux-Arts is known for the immense aesthetic diversity Press release: “Antônio Carlos Jobim, running throughout its different sections. highly-elaborate popular music” This reality is in stark contrast with academicism. -

Saverio MERCADANTE

SAVERIOMERCADANTE Flute Concertos Nos. 1, 2 and 4 Patrick Gallois, Flute and Conductor Sinfonia Finlandia Jyväskylä Saverio Mercadante (1795-1870): here, not only in the Largo, but also at various points in the which the soloist plays from the start, in the first of no fewer faster movements either side of it, providing an effective than five entries, one of which (the second) introduces a new Flute Concertos Nos. 1, 2 and 4 contrast to the more acrobatic writing and brighter rhythms. In theme and another (the fourth) sees a modulation to the Saverio Mercadante was born in 1795 in the southern Italian 18) and a trio for flute, violin and guitar (1816). The young the Allegro maestoso, the most demanding of the movements minor. These five sections alternate with four brief orchestral town of Altamura. Between 1808 and 1819 he studied the composer’s interest in the flute, an instrument which at that from a formal point of view, orchestral interludes separate interludes, reduced in both scale and significance. violin, cello, bassoon, clarinet and flute, as well as composition time had yet to be fully technically developed, stemmed three substantial passages in which the soloist is called on The title-page of the Flute Concerto No. 1, Op. 49, (under Giovanni Furno, Giacomo Tritto and Nicola Zingarelli), from his everyday life at the conservatory, where he was to play all kinds of embellishments, high-speed passages gives both its date of composition, 1813, and the name of its at the conservatory of Naples, then known as the Royal mixing with virtuoso teachers and fellow students – the best (including octave leaps, extended chromatic passages, dedicatee, Mercadante’s fellow student Pasquale Buongiorno, College of Music. -

The Art of Music :A Comprehensive Ilbrar

1wmm H?mi BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT or Hetirg W, Sage 1891 A36:66^a, ' ?>/m7^7 9306 Cornell University Library ML 100.M39 V.9 The art of music :a comprehensive ilbrar 3 1924 022 385 342 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924022385342 THE ART OF MUSIC The Art of Music A Comprehensive Library of Information for Music Lovers and Musicians Editor-in-Chief DANIEL GREGORY MASON Columbia UniveTsity Associate Editors EDWARD B. HILL LELAND HALL Harvard University Past Professor, Univ. of Wisconsin Managing Editor CESAR SAERCHINGER Modem Music Society of New Yoric In Fourteen Volumes Profusely Illustrated NEW YORK THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC Lillian Nordica as Briinnhilde After a pholo from life THE ART OF MUSIC: VOLUME NINE The Opera Department Editor: CESAR SAERCHINGER Secretary Modern Music Society of New York Author, 'The Opera Since Wagner,' etc. Introduction by ALFRED HERTZ Conductor San Francisco Symphony Orchestra Formerly Conductor Metropolitan Opera House, New York NEW YORK THE NASTIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC i\.3(ft(fliji Copyright, 1918. by THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC, Inc. [All Bights Reserved] THE OPERA INTRODUCTION The opera is a problem—a problem to the composer • and to the audience. The composer's problem has been in the course of solution for over three centuries and the problem of the audience is fresh with every per- formance. -

William and Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM AND MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth -

Professor Niecks on Melodrama Author(S): Frederick Niecks Source: the Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol

Professor Niecks on Melodrama Author(s): Frederick Niecks Source: The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, Vol. 42, No. 696 (Feb. 1, 1901), pp. 96-97 Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3366388 . Accessed: 21/12/2014 00:58 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.235.251.160 on Sun, 21 Dec 2014 00:58:46 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions L - g6 THE MUSICAL TIMES.-FEBRUARY I, I901. of any service is, of course, always undesirable. musical society as well as choir inspectorand con- But it is permissible to remind our young and ductor to the Church Choral Association for the enthusiastic present-day cathedral organists that the Archdeaconryof Coventry. In I898 he became rich store of music left to us by our old English church organistand masterof the choristersof Canterbury composers should not be passed by, even on Festival Cathedral,in succession to Dr. -

Małgorzata Bugaj Panoptikum 2019, 21:81-94

Małgorzata Bugaj Panoptikum 2019, 21:81-94. https://doi.org/10.26881/pan.2019.21.05 Małgorzata Bugaj University of Edinburgh “We understand each other, my friend”. The freak show and Victorian medicine in The Elephant Man. Anxieties around the human body are one of the main preoccupations in the cinema of David Lynch. Lynch’s films are littered with grotesque corporealities (such as the monstrous baby in Eraserhead¸1977; or Baron Harkonnen in The Dune, 1984) and those of disabled or crippled characters (the protagonist in the short Amputee; 1973; the one-armed man in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, 1992). The bodies in his films are often presented as fragmented (literally, cut off from the whole, or figuratively, by using close-ups) or distorted in the eye of the camera (a technique used, for example, in Wild at Heart, 1990, or Inland Empire, 2006). The director frequently highlights human biology, particularly in bodies that are shown to lose control over their physiological functions (vomiting blood in The Alphabet, 1968, or urinating in Blue Velvet, 1986). This interest in characters defined primarily through their abnormal corporeal forms is readily apparent in Lynch’s second feature The Elephant Man (1980) centring on a man severely afflicted with a disfiguring disease1. 5IFGJMN MPPTFMZCBTFEPO4JS'SFEFSJDL5SFWFTNFNPJSThe Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences (1923), revolves around three characters inspired by real- life personas: John Merrick (the titular ‘Elephant Man’ Joseph Carey Merrick, %PDUPS5SFWFT UIFBGPSFNFOUJPOFE4JS'SFEFSJDL5SFWFT and Bytes (Tom Norman, 1860-1930). Accordingly, the story shifts between dif- 1 It is worth noting that the film was released in the wake of a cultural rediscovery of the John Merrick story nearly a century after his death. -

Dossier Pedagogique

PINOCCHIO Concerts réservés aux élèves de l’école primaire (cycle 2) : Lundi 16 mars 2020 – 9h00 et 10h30 Mardi 17 mars 2020 – 9h00 et 10h30 Jeudi 19 mars 2020 – 9h00 et 10h30 Auditorium Henri Dutilleux de Douai DOSSIER PEDAGOGIQUE Pinocchio Laurent Petitgirard sur un texte d’Edouard Signolet d’après Carlo Collodi Récitante > Isabelle Carré-Legrand Orchestre de Douai – Région Hauts-de-France Illustrations > Laëtitia La Saux Présentation > Michèle Eloire Orchestre de Douai – Douai Trade Center – 100 rue Pierre Dubois 59500 Douai – Tél. 03 27 71 77 77 – [email protected] Pinocchio PINOCCHIO Musique de Laurent Petitgirard sur un texte d’Edouard Signolet d’après Carlo Collodi Le livre-CD est disponible chez Didier Jeunesse L’auteur : Né en 1881 sous la plume de l’écrivain toscan Carlo Collodi, Pinocchio s’impose comme l’enfant terrible de la littérature italienne. La version hollywoodienne des studios Disney s’éloigne du roman italien d’origine : le petit garçon au cœur tendre du maître américain diffère radicalement du gamin insupportable imaginé par Collodi. C’est ce personnage a priori peu sympathique que le dramaturge Edouard Signolet a choisi pour sa version de Pinocchio, dans laquelle le pantin de bois, têtu, malpoli et ingrat doit vivre ses aventures pour évoluer et grandir. Le compositeur : Né en 1950, Laurent Petitgirard a étudié le piano avec Serge Petitgirard et la composition avec Alain Kremski. Musicien éclectique, sa carrière de compositeur de musique symphonique, d’opéras et de musique de chambre se double d'une importante activité de chef d'orchestre. Laurent Petitgirard a également composé de nombreuses musiques de films pour des metteurs en scène tels Otto Preminger, Jacques Demy, Francis Girod, Peter Kassovitz. -

Mannheim Le 12 Nov:Bre Mon Trés Cher Pére!2 1778 I Arrived Here Well

0504.1 MOZART TO HIS FATHER, SALZBURG Mannheim le 12 Nov:bre Mon Trés cher Pére!2 1778 I arrived here well on the 6th and surprised all my good friends in a pleasant way; – praise and thanks be to God that I am once again in my beloved Mannheim! [5] I assure you that you would say the same if you were here; I am lodging with Mad:me Cannabich3 – who, along with her family and all good friends, was almost beside herself for joy when she saw me again; – we have not finished talking yet, for she is telling me all the stories and changes that have happened my absence; – [10] I have not yet eaten at home the whole time I have been here – for it is full-blooded, this fighting over me; in a word; as I love Mannheim, Mannheim loves me; – And I do not know for sure, I believe I will yet in the end be taken on4 here! – here, not in Munich; for the Elector5 would, I believe, <be very glad to have his residence in Manheim again>, [15] since he will not possibly be able <to put up> with the <crudities> of the <Bavarian gentlemen> for long! – You know that the Mannheim troupe6 is in Munich? – there they have already whistled the 2 leading actresses, Mad:me Toscani7 and Mad:me Urban,8 off the stage, and there was so much noise that <the Elector himself> leaned out of his <box> and said sh– – [20] but after no-one allowed themselves to be put off by that, he sent someone down, – but <Count Seau9>, after he said to some officers they should not make so much noise, <the Elector> didn’t like to see it, received this answer; – <it was with their good money that they got in> there and <they are not taking orders from anyone> – yet what a fool I am! [25] You will long since have heard this from our – ;10 Now here comes something; – perhaps I can earn 40 louis d’or11 here! – Admittedly I must stay here 6 weeks – or 2 months at the most; – Seiler’s troupe12 is here – who will already be known to you by renomè;13 – Herr von Dallberg14 is their director; – this man 1 This letter contains passages in "family code"; these are marked with angle brackets < >.