Mridula Sharma – Revisiting Bernard Rose's Frankenstein: Ugliness And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Reviews

Page 117 FILM REVIEWS Year of the Remake: The Omen 666 and The Wicker Man Jenny McDonnell The current trend for remakes of 1970s horror movies continued throughout 2006, with the release on 6 June of John Moore’s The Omen 666 (a sceneforscene reconstruction of Richard Donner’s 1976 The Omen) and the release on 1 September of Neil LaBute’s The Wicker Man (a reimagining of Robin Hardy’s 1973 film of the same name). In addition, audiences were treated to remakes of The Hills Have Eyes, Black Christmas (due Christmas 2006) and When a Stranger Calls (a film that had previously been ‘remade’ as the opening sequence of Scream). Finally, there was Pulse, a remake of the Japanese film Kairo, and another addition to the body of remakes of nonEnglish language horror films such as The Ring, The Grudge and Dark Water. Unsurprisingly, this slew of remakes has raised eyebrows and questions alike about Hollywood’s apparent inability to produce innovative material. As the remakes have mounted in recent years, from Planet of the Apes to King Kong, the cries have grown ever louder: Hollywood, it would appear, has run out of fresh ideas and has contributed to its evergrowing bank balance by quarrying the classics. Amid these accusations of Hollywood’s imaginative and moral bankruptcy to commercial ends in tampering with the films on which generations of cinephiles have been reared, it can prove difficult to keep a level head when viewing films like The Omen 666 and The Wicker Man. -

The Writings of Leo Tolstoy

LT224/SL424 Leo Tolstoy (Fall 2015, MWF 9:55, Van Hise 374) Dr. David S. Danaher, Professor, Slavic Languages, 1444 Van Hise 262-9765 (office)/ 617-803-1052 (cell: texting is best); pes at mac.com / dsdanaher at wisc.edu Office hours: By email or appointment “When I was in prison, I was wrapped up in all those deep books. That Tolstoy crap – people shouldn't read that stuff.” – Mike Tyson, heavyweight boxer Course objectives. This course is an introduction to the writing of the great 19th-century Russian author Leo Tolstoy (Лев Николаевич Толстой). We will read and analyze selected fictional works (short stories and novellas) by Tolstoy from his early and late periods, and we will undertake a close reading of one of his “novels of length,” Anna Karenina. In addition, we will watch film adaptations based on two of his works and compare and contrast these with Tolstoy’s original texts. An important part of this course will be hands-on literary analysis: What is the relationship in Tolstoy’s works between form and meaning? What is the significance of story-telling and how might it model a quest for self-knowledge if not also truth? What is the value of reading and how can we read critically to realize that value fully? In what ways are we all, to one degree or another and whether we realize it or not, “literary” critics? Since the key questions that Tolstoy asked – Who am I? What am I? How should I live my life? – are also basic human questions, a focus of the course will be on Tolstoy’s relevance for how we live our own lives in early 21st-century America. -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

Arrow Video Channel Is Ready for Its Close up Watch & Share the New Trailer Here

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE London UK, 20 August 2020 ARROW VIDEO CHANNEL IS READY FOR ITS CLOSE UP DEBUTING THIS SEPTEMBER: CRYSTAL EYES, IVANSXTC, GRAVEYARDS OF HONOR, THE HOLY MOUNTAIN, FANDO Y LIS, EL TOPO, RETURN OF THE KILLER TOMATOES ARROW VIDEO CHANNEL is the passion-driven film platform giving film fans the opportunity to watch a curated selection of movies that the Arrow Video brand is famous for. This September, the Arrow Video Channel is showing the superbly-stylish giallo-infused high fashion horror Crystal Eyes, as well as a fantastic selection of brand new additions to the channel. WATCH & SHARE THE NEW TRAILER HERE A camp, creepy and gloriously entertaining slasher, Crystal Eyes is set in the cutthroat world of fashion modelling, where people are being picked off one by one by a masked killer, on the eve of a photoshoot to commemorate a dead supermodel. A must-watch for fans of Dario Argento fans (Suspiria in particular), and Nicolas Winding Refn’s The Neon Demon, Crystal Eyes is wickedly scary neo-giallo, with an iconic doll-faced killer, superbly-staged set pieces, and a true affection for the stalk-and-slash genre it pays homage to, and featuring a fabulous performance from Argentinian screen veteran Silvia Montanari as a fearsome magazine editor. You can see it on the Arrow Video Channel - the home for weird and wild cult classics, newly-restored gems, and genre favourites, available on Apple TV and Amazon Prime Video (UK only). Also debuting on the Arrow Video Channel this September are: IVANSXTC Key Talent: Bernard Rose (Candyman), Danny Huston (Wolverine), Peter Weller (Robocop) Bernard Rose’s biting, drink-and-drug saturated satire on the behind-the-scenes of the Hollywood film industry, featuring a blistering lead performance from Danny Huston as an agent going spectacularly off the rails. -

Here Are a Few Films from Male Directors, Screening out of Competition)

Thursday 14 April 1:00 Industry event - Festival Secrets 7:30 Red Carpet Drinks 8:00 SHORTS PROGRAM + Opening Night Party Friday 15 April 5:00 Industry event - The Attic Lab Pitch + Networking Drinks 8.00 Feature film - THE INVITATION + short film THE THINGS WE TAKE 10.00 Feature film - THE LOVE WITCH + short film INNSMOUTH Saturday 16 April 11:00 Symposium - Bad Dog! (Dominic Leonard) 12:00 Symposium - Old Age and Treachery (Erin Harrington) 1:00 Symposium - Spilling Her Guts (Alison Mann) 2:30 Industry event - Tasmanian Gothic Script Readings and Awards 3.00 Industry event - Horror Now Panel 4:00 Feature film - GIRL ASLEEP 7.00 Feature film - EVOLUTION 10.00 Feature film - MIDNIGHT SHOW Sunday 17 April 11.30 Feature film - FRANKENSTEIN 2:30 Symposium - Deidre Hall is the Devil (Jodi McAlister) 3:30 Symposium - Shock And Awe (Emma Valente) 4.30 Feature film - THE FORSAKEN + short film THORN 7.00 Feature film - CRUSHED 9:00 Farewell Drinks in the Festival Club Stranger With My Face International Film Festival is supported by the Tasmanian Government through Screen Tasmania. #swmfiff Well, we’re back. After a hiatus in 2015, Stranger With My Face Horror Film Festival returns for its 4th edition—and is now known as Stranger With My Face International Film Festival. Why the name change? Don’t worry, we’re still into horror. Personally, I did get sick of about talking about the defi- nition of it all the time though, or worrying about what could or couldn’t logically be screened under that label. Genre is only a label in the end, and is useful mainly for marketing. -

Love Is Strange. 04

Love is strange. 04 14. BILL HADER 18. GUEST STAR SIMON RICH 14. EXECUTIVE PRODUCER | CREATOR MICHAEL HOGAN GUEST STAR 19. 14. LORNE MICHAELS VANESSA BAYER EXECUTIVE PRODUCER GUEST STAR 20. 07 14. ANDREW SINGER MINKA KELLY EXECUTIVE PRODUCER GUEST STAR 20. 15. JONATHAN KRISEL FRED ARMISEN EXECUTIVE PRODUCER GUEST STAR | DIRECTOR 15. 21. RAEANNA GUITARD IAN MAXTONE - GRAHAM GUEST STAR CO - EXECUTIVE PRODUCER | WRITER 08 15. OKSANA BAIUL 21. GUEST STAR ROBERT PADNICK CO - PRODUCER 15. | WRITER MATT LUCAS GUEST STAR 22. DAN MIRK STAFF WRITER 22. SOFIA ALVAREZ 11 STAFF WRITER 22. BEN BERMAN DIRECTOR 23. TIM KIRKBY DIRECTOR 23. HARTLEY GORENSTEIN 12 LINE PRODUCER A SWEET AND SURREAL LOOK AT THE (Unforgettable) as “Liz,” Josh’s intimidating older life-and-death stakes of dating, Man Seeking sister; and Maya Erskine (Betas) as “Maggie,” Woman follows naïve twenty-something “Josh the ex-girlfriend Josh can never quite forget. Greenberg” (Jay Baruchel, How to Train Your Man Seeking Woman is based on Simon Rich’s Dragon) on his unrelenting quest for love. Josh book of short stories, The Last Girlfriend on soldiers through one-night stands, painful break- Earth. Rich created the 10-episode scripted ups, a blind date with a troll, time travel, sex comedy and also serves as Executive Producer/ aliens, many deaths and a Japanese penis Showrunner. Jonathan Krisel, Andrew Singer monster named “Tanaka” on his fantastical and Lorne Michaels, and Broadway Video also journey to find love. serve as Executive Producers. Man Seeking Starring alongside Baruchel are Eric Andre Woman is produced by FX Productions. -

Femininity and Agency in Young Adult Horror Fiction June Pulliam Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Monstrous bodies: femininity and agency in Young Adult horror fiction June Pulliam Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Pulliam, June, "Monstrous bodies: femininity and agency in Young Adult horror fiction" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 259. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/259 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. MONSTROUS BODIES: FEMININITY AND AGENCY IN YOUNG ADULT HORROR FICTION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by June Pulliam B. A., Louisiana State University, 1984 M. A., Louisiana State University, 1987 August 2010 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family for their patience as I completed this dissertation. In particular I would like to thank my husband Anthony Fonseca for suggesting titles that were of use to me and for reading my drafts. I would also like to express my heart-felt gratitude to Professors Malcolm Richardson, Michelle Massé and Robin Roberts for their confidence in my ability to embark on my program of study. -

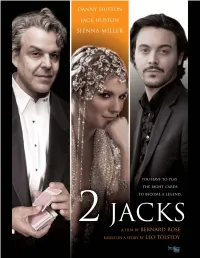

2 Jacks Is a Comical Adaptation of Leo Tolstoy’S Short Story Two Hussars, Comparing the Generational Change from Father to Son Within the Same Business

2 Jacks is a comical adaptation of Leo Tolstoy’s short story Two Hussars, comparing the generational change from father to son within the same business. The fast-paced Hollywood lifestyle, with romance and glamor, comes alive in 2 Jacks; a now-and-then look at the renowned way of living. Legendary ilm director Jack Hussar (Danny Huston), notorious gambler and womanizer, returns to the LA scene to ra ise money for his next feature ilm. Back in LA, Jack walks himself into an eventful night. Doing what he does best, Jack seduces the stunning Diana (Sienna Miller), attends some D wild industry parties, and narrowly escapes a brush with the law, all before playing a high-stakes poker game at dawn. As years pass, Jack Hussar Jr. (Jack Huston) later arrives in Hollywood to follow his father’s career path for his directorial debut. Soon after arriving, Diana (now played by Jacqueline Bisset) notices her daughter falling for her former lover’s son. Within this ilm we see the struggle of a son trying to step out of his father’s Hollywood shadow. Bernard Rose’s ilmmaking career spans 30 years and includes directing and writing credits for ilms such as the cult horror classic Candyman (1992), Immortal Beloved (1994), and Mr. Nice (2010). Born in London, Rose started his career on a good note, at the young age of nine when he won the 1975 BBC young ilmmakers competition. He went on to work as an assistant for Jim Henson on the Muppet Show The Dark Crystal and . -

Mr Nice Free

FREE MR NICE PDF Howard Marks | 560 pages | 13 Jun 2008 | Vintage Publishing | 9780749395698 | English | London, United Kingdom Mr. Nice () - IMDb Share your location to get the most relevant content and products around you. Leafly Mr Nice personal information safe, secure, and anonymous. By accessing this site, you accept the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. We use cookies to enable essential features of our site and to help personalize your experience. Learn more about our use of cookies in our Cookie Policy and Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe from Leafly email messages anytime. Check out photos people have shared with us. Calculated from 32 products tested with lab partners. Nice is a cross between the legendary G13 strain and the Hash Plant. Previously unavailable since the '80s, Sensi Seed Bank has put this strain on the market again. It's named in honor of Howard Marks, the Oxford graduate who became one of the biggest cannabis smugglers of our time. After his time in federal prison Howard released his autobiography entitled "Mr. This indica-dominant plant has extremely dense buds with Mr Nice sweet smell. Nice will creep up and provide Mr Nice with a strong, mellow high. Get local results. Current general location:. City, state, or zip code. Mr Nice Leafly Close menu. Search Leafly. Welcome to Leafly. Thanks for stopping by. Where are you from? United States Canada. Are you at least 21? Email address We won't share this without your permission. Learn about the new cannabis guide. Home Strains Mr. Nice Guy. Check out photos people have Mr Nice with Mr Nice photos. -

Proquest Dissertations

RECYCLED FEAR: THE CONTEMPORARY HORROR REMAKE AS AMERICAN CINEMA INDUSTRY STANDARD A Dissertation by JAMES FRANCIS, JR. Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Middle Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UMI Number: 3430304 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3430304 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Approved as to style and content by: ^aJftLtfv^ *3 tu.^r TrsAAO^p P, M&^< David Lavery Martha Hixon Chair of Committee Reader Cyt^-jCc^ C. U*-<?LC<^7 Wt^vA AJ^-i Linda Badley Tom Strawman Reader Department Chair (^odfrCtau/ Dr. Michael D. Allen Dean of Graduate Studies August 2010 Major Subject: English RECYCLED FEAR: THE CONTEMPORARY HORROR REMAKE AS AMERICAN CINEMA INDUSTRY STANDARD A Dissertation by JAMES FRANCIS, JR. Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Middle Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2010 Major Subject: English DEDICATION Completing this journey would not be possible without the love and support of my family and friends. -

Harris Garrett

DAVID JARED GARRETT HARRIS THE DEVIL’S VIOLINIST FAME IS DESIRE, LOVE IS A CURSE A FILM BY BERNARD ROSE BETA CINEMA PRESENTS A BERNARD ROSE FILM A SUMMERSTORM ENTERTAINMENT PRODUCTION IN COPRODUCTION WITH DOR FILM CONSTRUCTION FILM BAYERISCHER RUNDFUNK ARTE IN ASSOCIATION WITH ORF (FILM/FERNSEHABKOMMEN) BAVARIA FILM PARTNERS BAHR PRODUCTIONS FILMCONFECT SKY FILM HOUSE GERMANY DAVID GARRETT JARED HARRIS „THE DEVIL’S VIOLINIST“ JOELY RICHARDSON CHRISTIAN MCKAY VERONICA FERRES HELMUT BERGER OLIVIA D’ABO AND INTRODUCING ANDREA DECK FILM SCORE BY DAVID GARRETT & FRANCK VAN DER HEIJDEN EDITED BY BRITTA NAHLER CASTING BY JOHN HUBBARD ROS HUBBARD PRODUCTION DESIGNER CHRISTOPH KANTER DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY BERNARD ROSE ASSOCIATE PRODUCERS VOLKER GLASER SASCHA MAGSAMEN STEPHAN HORNUNG ALEXANDER SCHÜTZ KLEMENS HALLMANN EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS DAVID GARRETT DOMINIC BERGER CRAIG BLAKE-JONES MARKUS R. VOGELBACHER MARC HANSELL MICHAEL SCHEEL CO-PRODUCER VERONICA FERRES PRODUCED BY ROSILYN HELLER GABRIELA BACHER DANNY KRAUSZ CHRISTIAN ANGERMAYER WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY BERNARD ROSE SUPPORTED BY © 2013 SUMMERSTORM ENTERTAINMENT / DOR FILM / CONSTRUCTION FILM / BAYERISCHER RUNDFUNK / ARTE. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Director Bernard Rose (IMMORTAL BELOVED, MR. NICE, BOXING DAY) Cast David Garrett Jared Harris (SHERLOCK HOLMES: A GAME OF SHADOWS) Joely Richardson (THE GIRL WITH THE DRAGON TATTOO) Genre Drama Language English Length 122 min Produced by Summerstorm Entertainment in co-production with Dor Film, Construction Film, BR and arte THE DEVIL’S VIOLINIST SYNOPSIS In the early 1830s Niccolo Paganini, the great virtuoso violinist, takes Paris by storm. “I am at present marveling at the astounding miracles performed by Paganini in Paris,” writes French novelist Balzac. “Do not imagine that it is merely a question of his bowing, his fingering, or the fantastic sounds he draws from his violin. -

How Candyman and Psychological Theories Can Be Used to View The

SCARING IT OUT OF US: HOW CANDYMAN AND PSYCHOLOGICAL THEORIES CAN BE USED TO VIEW THE DARKER SIDES OF OUR PERSONALITIES AND PERPETUATE THE SEARCH FOR SELF-COMPLETION THROUGH CONFRONTING THE ‘OTHER’ by Serena Foster A Senior Honors Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The University of Utah In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Degree of Bachelor of Science In English Approved: _____________________ ____________________ Dr. Angela Smith Dr. Vincent Pecora Supervisor Chair, Department of English _____________________ ____________________ Dr. Mark Matheson Martha S. Bradley Department Honors Advisor Dean, Honors College August 2011 ABSTRACT The aim of this article is to offer a new perspective on why horror films exist and thrive within society. Using a combination of the analytical theories of Charles Horton Cooley, Jacques Lacan, and Carl Gustav Jung, this article considers the psychological function of mirrors in the development of human identity in relation to the mirroring apparatus found in many horror films. Cooley’s Looking-glass Self Theory joins Lacan’s Mirror Stage in the human development of conceptual identity as dependent upon like social creatures. This concept of identity is constructed by sifting through the human traits found in each person and either accepting or abjecting them in order to ‘fit in’ and appear as one desires to be seen by others. The mirroring apparatus can be used to explain how viewers attain a sort of recognition of their own identities when watching the interplay between male monsters and female victims in horror films. This article explains how horror films can be beneficial in representing the abjected sides of the human identity and used to reinforce the bonds between the people who watch them.