M a T a N U Sk a So C C Er C Lu B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHILADELPHIA UNION V PORTLAND TIMBERS (Sept

PHILADELPHIA UNION v PORTLAND TIMBERS (Sept. 10, PPL Park, 7:30 p.m. ET) 2011 SEASON RECORDS PROBABLE LINEUPS ROSTERS GP W-L-T PTS GF GA PHILADELPHIA UNION Union 26 8-7-11 35 35 30 1 Faryd Mondragon (GK) at home 13 5-1-7 22 19 15 3 Juan Diego Gonzalez (DF) 18 4 Danny Califf (DF) 5 Carlos Valdes (DF) Timbers 26 9-12-5 32 33 41 MacMath 6 Stefani Miglioranzi (MF) on road 12 1-8-3 6 7 22 7 Brian Carroll (MF) 4 5 8 Roger Torres (MF) LEAGUE HEAD-TO-HEAD 25 Califf Valdes 15 9 Sebastien Le Toux (FW) ALL-TIME: 10 Danny Mwanga (FW) Williams G Farfan Timbers 1 win, 1 goal … 7 11 Freddy Adu (MF) Union 0 wins, 0 goals … Ties 0 12 Levi Houapeu (FW) Carroll 13 Kyle Nakazawa (MF) 14 Amobi Okugo (MF) 2011 (MLS): 22 9 15 Gabriel Farfan (MF) 5/6: POR 1, PHI 0 (Danso 71) 11 16 Veljko Paunovic (FW) Mapp Adu Le Toux 17 Keon Daniel (MF) 18 Zac MacMath (GK) 19 Jack McInerney (FW) 16 10 21 Michael Farfan (MF) 22 Justin Mapp (MF) Paunovic Mwanga 23 Ryan Richter (MF) 24 Thorne Holder (GK) 25 Sheanon Williams (DF) UPCOMING MATCHES 15 33 27 Zach Pfeffer (MF) UNION TIMBERS Perlaza Cooper Sat. Sept. 17 Columbus Fri. Sept. 16 New England PORTLAND TIMBERS Fri. Sept. 23 at Sporting KC Wed. Sept. 21 San Jose 1 Troy Perkins (GK) 2 Kevin Goldthwaite (DF) Thu. Sept. 29 D.C. United Sat. Sept. 24 at New York 11 7 4 Mike Chabala (DF) Sun. -

De Jeugdvoetbaltrainer

De JeugdVoetba lTrainer 4e JAARGANG | FEBRUARI 2015 | www.devoetbaltrainer.nl nummer nummer 30 Percy van Lierop Koningsoefeningen en provocatieregels Provocatieve coaching Hulpmiddel voor beïnvloeding Thema: Verdedigen tegen twee spitsen A-jeugd Mark Lakwijk B-jeugd Jeroen Geerink C-jeugd Jochem de Weerdt D-jeugd Marc Jansen 33_jvtcover.indd 33 22-01-15 11:32 De JeugdVoetba lTrainer Tekst: Paul Geerars Percy van Lierop: ‘Straatkwaliteiten en flexibiliteit maken het verschil’ Koningsoefeningen en provocatieregels Percy van Lierop was zeven jaar lang werkzaam bij Red Bull Salzburg, in draaien denken bij het horen van de naam Wiel Coerver, maar dan doe je verschillende functies tot en met Hoofd Jeugdopleiding. Geïnspireerd door hem veel tekort. Dat is natuurlijk ook gedeeltelijk zijn eigen schuld, door zijn Wiel Coerver zette hij daar een manier van werken neer die vleugels gaf aan manier van presenteren, eigengereid als hij was. Ik weet dat zijn ideeën op de talentenfabriek van de Oostenrijkse club. Nu probeert hij hetzelfde te het gebied van voetbaltraining bedoeld waren om uiteindelijk in het stadion, bewerkstelligen in de buurt van München. De Voetbaltrainer tekende zijn 11:11, goed te voetballen. Uiteindelijk gaat het om het proces van 1:1 tot interessante verhaal op. 11:11 en dat spelers de juiste beslis- singen kunnen nemen en uiteindelijk het verschil kunnen maken. Dat de Percy van Lierop speelde zelf in de Deutsche Fussball Internat, een voet- basis daarvoor een goede (technische) jeugd van PSV en trainde als zeven- balschool in Bad Aibling, onder de basisvaardigheid is door middel van tienjarige met het eerste team mee. In rook van München (samenwerkings- vereenvoudigde trainingsvormen, daar 1996 begon zijn trainersloopbaan. -

Frans Hoek: ‘Er Wordt Meer 24 Wim Koevermans: F.: 088- 850 86 13 Geworden

Coaches Betaald Voetbal Magazine Ronald Koeman: ‘Bondscoach van eigen land blijft erebaan’ pagina 13 -16 Uitgave 08 | Juni 2014 Inhoud Colofon Coaches Betaald Voetbal Magazine is het magazine voor de leden en De trainer/coach: relaties van de CBV. Gehele of gedeeltelijke overname bewaker EN DRAGER van van artikelen is alleen toegestaan na schriftelijke toestemming van de CBV. DE Voetbalcultuur Coaches Betaald Voetbal Magazine verschijnt tweemaal per jaar. Met de aftrap van de Coach Tour ‘Hollandse Meesters’ als laatste Redactie programma-onderdeel van het Nederlands Trainerscongres, op Rob Heethaar, Petra Balster vrijdag 9 mei in Zwolle gehouden, heeft de vereniging Coaches Ontwerp en vormgeving Guts Communication Betaald Voetbal een eerste aanzet gegeven tot het beter positioneren van de trainer/coach. De trainer/coach verdient een Foto’s: ProShots meer bepalende positie aan de overlegtafel en in het speelveld Hans Peter van Velthoven (pag. 27) van sport, clubs en bonden. Met de Coach Tour willen we de Drukwerk Hollandse trainer/coach nadrukkelijker in beeld brengen als Drukkerij Meijerink bewaker en drager van de Hollandse Voetbalcultuur. Advertenties 09 Advertenties dienen een duidelijke link te hebben met de CBV of haar We zijn van plan dit kalenderjaar nog minimaal twee sessies te werkelijk om gaat, zitten we niet aan tafel. Dat kan en mag relaties. De redactie heeft hierin het organiseren en hopen daarbij, in navolging van Co Adriaanse niet langer zo zijn.” 03 Voorwoord: Bewaker en 18 Trainerscongres valt in de laatste oordeel. Voor informatie over en John van den Brom, op de welwillende medewerking van drager van de Voetbalcultuur smaak advertenties kunt u contact opnemen een paar van onze eigen ‘ambassadeurs’. -

Faculty of Business Administration and Economics

FACULTY OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION AND ECONOMICS Working Paper Series Working Paper No. 2018-10 THE SUPERSTAR CODE - DECIPHERING KEY CHARACTERISTICS AND THEIR VALUE Franziska Prockl May 2018 THE SUPERSTAR CODE - DECIPHERING KEY CHARACTERISTICS AND THEIR VALUE. Franziska Prockl Paderborn University, Management Department, Chair of Organizational, Media and Sports Economics, Warburger Str. 100, D-33098 Paderborn. May 2018 Working Paper ABSTRACT The purpose of the presented research is to advance the superstar literature on the aspect of superstar’s characteristics and value. Typically, superstar research is faced with one problem: They apply the same criteria to determine who their superstars are as to describe them later because they lack “an objective measure of star quality” (Krueger, 2005, p.18). To avoid this complication, the author chose to study Major League Soccer’s (MLS) designated players as this setting present a unique, as discrete, assignment of star status. MLS has formally introduced stars in 2007 under the designated player (DP) rule which delivers over 100 star-observations in the last ten years to investigate MLS strategy of star employment. The insights from this data set demonstrate which characteristics are relevant, whether MLS stars can be categorized as Rosen or Adler stars, and what the MLS pays for and in this sense values most. A cluster analysis discovers a sub group of ten stars that stand out from the others, in this sense superstars. A two-stage regression model confirms the value stemming from popularity, leadership qualities, previous playing level, age and national team experience but refutes other typical performance indicators like games played and goals scored or position. -

Madrid Close In

PREVIEW ISSUE FOUR – 24TH APRIL 2012 MADRID CLOSE IN REAL TAKE THE SPOILS IN THE EL CLASICO AND CLOSE IN ON THE SILVERWARE After a poor week for both sides in Europe, Real and Barca were desperate to grab a win against their biggest rivals on a dramatic, rain-lashed Saturday night at the Nou Camp. It was Real that grabbed the vital win and probably clinched the La Liga title. Los Merengues went ahead through German midfielders Sami Khedira and were comfortable for long periods, but Barca’s Chilean substitute Alexis Sánchez equalised with just 20 minutes remaining. Cristiano Ronaldo’s clinical strike just three minutes later settled the game with Madrid now seven points clear, with only four games remaining. Madrid coach José Mourinho named an very attacking team and his side began the better. Ronaldo’s early header from a corner brought a superb flying save from goalkeeper Víctor Valdés. His opposite number Iker Casillas was then quickly off his line when full-back Dani Alves dispossessed Sergio Ramos. The game was being played at a fearsome pace and French striker Karim Benzema brought the best out of Valdés again. Barca thought they had gone front when Alves had the ball in the net after a Cristian Tello run, but the youngster had been flagged offside. INSIDE THIS WEEK’S WFW Real’s brave start was rewarded when Pepe’s header from another corner was half- - RESULTS ROUND-UP ON ALL MAJOR stopped by Valdes and Khedira tackled an COMPETITIONS FROM AROUND THE hesitant Carles Puyol to push the ball into the WORLD net to put Madrid ahead. -

Onside: a Reconsideration of Soccer's Cultural Future in the United States

1 ONSIDE: A RECONSIDERATION OF SOCCER’S CULTURAL FUTURE IN THE UNITED STATES Samuel R. Dockery TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin May 8, 2020 ___________________________________________ Matthew T. Bowers, Ph.D. Department of Kinesiology Supervising Professor ___________________________________________ Elizabeth L. Keating, Ph.D. Department of Anthropology Second Reader 2 ABSTRACT Author: Samuel Reed Dockery Title: Onside: A Reconsideration of Soccer’s Cultural Future in the United States Supervising Professors: Matthew T. Bowers, Ph.D. Department of Kinesiology Elizabeth L. Keating, Ph.D. Department of Anthropology Throughout the course of the 20th century, professional sports have evolved to become a predominant aspect of many societies’ popular cultures. Though sports and related physical activities had existed long before 1900, the advent of industrial economies, specifically growing middle classes and ever-improving methods of communication in countries worldwide, have allowed sports to be played and followed by more people than ever before. As a result, certain games have captured the hearts and minds of so many people in such a way that a culture of following the particular sport has begun to be emphasized over the act of actually doing or performing the sport. One needs to look no further than the hours of football talk shows scheduled weekly on ESPN or the myriad of analytical articles published online and in newspapers daily for evidence of how following and talking about sports has taken on cultural priority over actually playing the sport. Defined as “hegemonic sports cultures” by University of Michigan sociologists Andrei Markovits and Steven Hellerman, these sports are the ones who dominate “a country’s emotional attachments rather than merely representing its callisthenic activities.” Soccer is the world’s game. -

Dutch Pro Academy Training Sessions Vol 1

This ebook has been licensed to: Bob Hansen ([email protected]) If you are not Bob Hansen please destroy this copy and contact WORLD CLASS COACHING. This ebook has been licensed to: Bob Hansen ([email protected]) Dutch Pro Academy Training Sessions Vol 1 By Dan Brown Published by WORLD CLASS COACHING If you are not Bob Hansen please destroy this copy and contact WORLD CLASS COACHING. This ebook has been licensed to: Bob Hansen ([email protected]) First published September, 2019 by WORLD CLASS COACHING 3404 W. 122nd Leawood, KS 66209 (913) 402-0030 Copyright © WORLD CLASS COACHING 2019 All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher. Author – Dan Brown Edited by Tom Mura Front Cover Design – Barrie Bee Dutch Pro Academy Training Sessions I 1 ©WORLD CLASS COACHING If you are not Bob Hansen please destroy this copy and contact WORLD CLASS COACHING. This ebook has been licensed to: Bob Hansen ([email protected]) Table of Contents 3 Overview and Itinerary 8 Opening Presentation with Harry Jensen, KNVB 10 Notes from Visit to ESA Arnhem Rijkerswoerd Youth Club 12 Schalke ’04 Stadium and Training Complex Tour 13 Ajax Background 16 Training Session with Harry Jensen, KNVB 19 Training Session with Joost van Elden, Trekvogels FC 22 Ajax Youth Team Sessions 31 Ajax U13 Goalkeeper Training 34 Ajax Reserve Game & Attacking Tendencies Dutch Pro Academy Training Sessions I 2 ©WORLD CLASS COACHING If you are not Bob Hansen please destroy this copy and contact WORLD CLASS COACHING. -

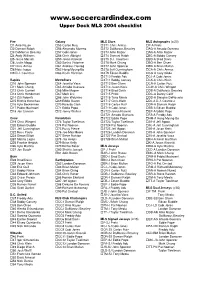

Upper Deck Major League MLS 2004

www.soccercardindex.com Upper Deck MLS 2004 checklist Fire Galaxy MLS Stars MLS Autographs (x/20) 1 Ante Razov 55 Carlos Ruiz ST1 Chris Armas P-A Preki 2 Damani Ralph 56 Alejandro Moreno ST2 DaMarcus Beasley AG-A Amado Guevara 3 DaMarcus Beasley 57 Cobi Jones ST3 Ante Razov AR-A Ante Razov 4 Andy Williams 58 Chris Albright ST4 Damani Ralph BC-A Bobby Convey 5 Jesse Marsch 59 Jovan Kirovski ST5 D.J. Countess BD-A Brad Davis 6 Justin Mapp 60 Sasha Victorine ST6 Mark Chung BO-A Ben Olsen 7 Chris Armas 61 Andreas Herzog ST7 John Spencer BR-A Brian Mullan 8 Nate Jaqua 62 Hong Myung-Bo ST8 Jeff Cunningham CA-A Chris Armas 9 D.J. Countess 63 Kevin Hartman ST9 Edson Buddle CG-A Cory Gibbs ST10 Freddy Adu CJ-A Cobi Jones Rapids MetroStars ST11 Bobby Convey CK-A Chris Klein 10 John Spencer 64 Joselito Vaca ST12 Ben Olsen CR-A Carlos Ruiz 11 Mark Chung 65 Amado Guevara ST13 Jason Kreis CW-A Chris Wingert 12 Chris Carrieri 66 Mike Magee ST14 Brad Davis DB-A DaMarcus Beasley 13 Chris Henderson 67 Mark Lisi ST15 Preki DC-A Danny Califf 14 Zizi Roberts 68 John Wolyniec ST16 Tony Meola DD-A Dwayne DeRosario 15 Ritchie Kotschau 69 Eddie Gaven ST17 Chris Klein DJ-A D.J. Countess 16 Kyle Beckerman 70 Ricardo Clark ST18 Carlos Ruiz DR-A Damani Ralph 17 Pablo Mastroeni 71 Eddie Pope ST19 Cobi Jones EB-A Edson Buddle 18 Joe Cannon 72 Jonny Walker ST20 Jovan Kirovski EP-A Eddie Pope ST21 Amado Guevara FA-A Freddy Adu Crew Revolution ST22 Eddie Pope HM-A Hong Myung-Bo 19 Chris Wingert 73 Taylor Twellman ST23 Taylor Twellman JA-A Jeff Agoos 20 Edson Buddle 74 -

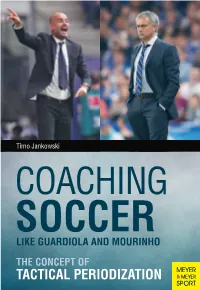

Tactical Periodization Has Become the Preferred Training Theory of FC Aarau

TIMO JANKOWSKI TIMO JANKOWSKI Timo Jankowski holds the UEFA A License and is Life Kinetic and COACHING Functional Fitness trainer. Following A soccer player is more than the sum of his parts: endurance, speed, shooting technique, his jobs as coach of the German passing technique, and many more. Football Association as well as of All of these factors need to be turned into one system to create good players. Traditional the U16 of Grasshoppers Zurich, Jan- training theory doesn’t achieve that because each skill is trained individually. kowski currently trains the U16 team This is why the concept of Tactical Periodization has become the preferred training theory SOCCER of FC Aarau. In addition, he runs a ISBN 978-1-78255-062-4 for many of the current most successful soccer coaches: Pep Guardiola, José Mourinho, sports center with a hotel and soccer Diego Simeone, André Villas-Boas, and many others train according to these principles. school. He is the author of Successful $ 16.95 US/$ 29.95 AUS/£ 12.95 UK/b 16.95 German Soccer Tactics. By creating match-like situations in practice, players learn to link their technical, tactical, Timo Jankowski and athletic abilities to match intelligence. They will learn to transfer their skills to soccer LIKE GUARDIOLA AND MOURINHO matches and they can improve endurance, technique, and tactics all at the same time while enjoying the practice sessions more. For this book, the author has evaluated and analyzed hundreds of training sessions and has tailored exercises to specific demands. All exercises are performed with a ball so that players learn to apply each skill to the game. -

Raising a Red Card: Why Freddy Adu Should Not Be Allowed to Play Professional Soccer Jenna Merten

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 15 Article 12 Issue 1 Fall Raising a Red Card: Why Freddy Adu Should Not Be Allowed to Play Professional Soccer Jenna Merten Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Jenna Merten, Raising a Red Card: Why Freddy Adu Should Not Be Allowed to Play Professional Soccer, 15 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 205 (2004) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol15/iss1/12 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS RAISING A RED CARD: WHY FREDDY ADU SHOULD NOT BE ALLOWED TO PLAY PROFESSIONAL SOCCER INTRODUCTION "Ifwe don't stand up for children, then we don't stand for much."1 The United States is a nation that treasures its children. 2 Recognizing children's vulnerability, the United States has enacted many laws to protect them. For example, federal and state laws allow children to disaffirm contracts, protect children's sexual health and development through statutory rape laws, prevent children from viewing overtly sexual and violent movies and television shows, require children to follow many restrictions to obtain a 3 driver's license, and prohibit children from using tobacco and alcohol. Additionally, the government protects children's labor and employment. Realizing the increase in the number of child laborers during the Industrial Revolution and the poor working conditions and health problems child laborers suffered, Congress enacted the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) in 1938.4 Through the FLSA, Congress aimed to protect children's health and well-being by preventing them from employment itself and limiting the hours of employment and types of employment children may obtain.5 In the years after it became law, the FLSA was successful in eradicating the most 1. -

Upper Deck Major League MLS 2005

www.soccercardindex.com Upper Deck MLS 2005 checklist Fire Revolution MLS Goal Men MLSignatures (x/25) 1 Tony Sanneh 59 Pat Noonan GM1 Justin Mapp AE-S Alecko Eskandarian 2 Ante Razov (Crew) 60 Taylor Twellman GM2 Joe Cannon AG-S Amado Guevara 3 Andy Herron 61 Steve Ralston GM3 Edson Buddle AR-S Ante Razov 4 Chris Armas 62 Andy Dorman GM4 Jon Busch BC-S Brian Ching 5 Kelly Gray 63 Jose Cancela GM5 Eddie Johnson BM-S Brian Mullan 6 Nate Jaqua 64 Clint Dempsey GM6 Freddy Adu CA-S Chris Armas 7 Justin Mapp 65 Matt Reis GM7 Jaime Moreno CD-S Clint Dempsey 66 Jay Heaps GM8 Josh Wolff CJ-S Cobi Jones Rapids GM9 Nick Rimando CR-S Carlos Ruiz 8 Joe Cannon Earthquakes GM10 Davy Arnaud DA-S Davy Arnaud 9 Pablo Mastroeni 67 Craig Waibel GM11 Carlos Ruiz DK-S Dema Kovalenko 10 Landon Donovan (Galaxy) 68 Ryan Cochrane GM12 Amado Guevara EB-S Edson Buddle 11 Jean Philippe Peguero 69 Pat Onstad GM13 Pat Noonan EG-S Eddie Gaven 12 Mark Chung 70 Brian Ching GM14 Taylor Twellman EP-S Eddie Pope 13 Jordan Cila 71 Brian Mullan GM15 Pat Onstad FA-S Freddy Adu 14 Chris Henderson 72 Dwayne De Rosario GM16 Brian Ching JA-S Jonny Walker 73 Troy Dayak GM17 Ante Razov JB-S Jon Busch Crew 74 Eddie Robinson GM18 Jeff Cunningham JC-S Joe Cannon 15 Edson Buddle JG-S Jeff Agoos 16 Jon Busch CD Chivas USA MLS Jersey JK-S Jason Kreis 17 Jeff Cunningham (Rapids) 75 Arturo Torres BC-J Brian Ching JM-S Justin Mapp 18 Ross Paule 76 Orlando Perez CA-J Chris Armas JO-S Jaime Moreno 19 Klye Martino 77 Ezra Hendrickson CR-J Carlos Ruiz JP-S Jean Philippe Peguero 20 Simon Elliott -

UEFA Cup to Arrive in Rotterdam on Friday

Media Release Route de Genève 46 Case postale Communiqué aux médias CH-1260 Nyon 2 Union des associations Tel. +41 22 994 45 59 européennes de football Medien-Mitteilung Fax +41 22 994 37 37 uefa.com [email protected] Date: 08/04/2002 No. 57 - 2002 UEFA Cup to arrive in Rotterdam on Friday Trophy to be handed back by Liverpool FC at City Hall and displayed till May 8 final On Friday 12 April the UEFA Cup will arrive in Rotterdam and will be put on display to the public until the UEFA Cup final, which is to be played at Stadion Feijenoord, more popularly known as De Kuip, on Wednesday 8 May. The occasion will be marked by a special event at the City Hall in Rotterdam, starting at 13.00, with the official handover ceremony scheduled to start at 13.30 in the Burgerzaal. The UEFA Cup will be handed back to UEFA by Liverpool FC, winners of last season’s thrilling and dramatic final at the Westfalenstadion in Dortmund. The English club will be represented by Chief Executive Rick Parry and manager Gérard Houllier. Once the trophy has been returned to UEFA, it will immediately be handed over to the Lord Mayor of Rotterdam, Ivo Opstelten, for safe keeping until the final. Although De Kuip has been the scenario for some memorable finals – the last one having been the EURO 2000 final between Italy and France – this is only the second time that the UEFA Cup will have been presented to the winning team in the stadium.