Chapter 5. the Integration of Youth Soccer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 Women's Soccer Guide.Indd Sec1:87 10/17/2014 12:43:12 PM Bbuffsuffs Inin Thethe Leagueleague

BBuffsuffs InIn thethe LeagueLeague Th e National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL) is the top level professional women’s soccer league in the United States. It began play in spring 2013 with eight teams: Boston Breakers, Chicago Red Stars, FC Kansas City, Portland Th orns FC, Seattle Reign FC, Sky Blue FC, the Washington Spirit and the Western New York Flash. Th e Houston Dash joined the league in 2014. Based in Chicago, the NWSL is supported by the United States Soccer Federation, Canadian Soccer Association and Federation of Mexican Football. Each of the league’s nine clubs will play a total of 24 games during a 19-week span, with the schedule beginning the weekend of April 12-13 and concluding the weekend of Aug. 16-17. Th e top four teams will qualify for the NWSL playoff s and compete in the semifi nals on Aug. 23-24. Th e NWSL will crown its inaugural champion aft er the fi nal on Sunday, Aug. 31. Nikki Marshall (2006-09): Defender, Portland Th orns FC At Colorado: Holds 20 program records ... Th e all-time leading scorer with 42 goals ... Leads the program with 93 points, 18 game-winning goals and 261 shots attempted ... Set class records as a freshman and sophomore with 17 and nine goals, respectively ... Scored the fastest regulation and overtime goals in CU history, taking less than 30 seconds to score against St. Mary’s College in 2009 (8-1) and against Oklahoma in 2007 (2-1, OT) ... Ranks in the top 10 in 32 other career, season and single game categories .. -

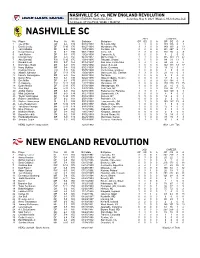

MLS Game Guide

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

MLS: Five Things to Watch Post All-Star Game

MLS: Five Things to Watch Post All-Star Game Author : Steven Jotterand Tonight the soccer world turns to Chicago, Illinois. Well, sort of. MLS will field their best against the epic Real Madrid in a glorified exhibition match. This All-Star game signals a transition to the second half of the season. Clubs will begin to turn up the heat as the hunt for the Cup begins. Here are five things to look out for post the All-Star game: LA Galaxy & Orlando City’s Push: In 2016, the Seattle Sounders lost 12 of their first 20 games. Two days after their 12th loss, they sacked Sigi Schmid and hired Brian Schmetzer as interim. One day after naming their new man in charge, Seattle made a splash and signed creative Uruguayan midfielder Nicklas Lodeiro as a Designated Player. A club that was trending nowhere, changed their fortunes around. Within weeks, they were one of the most feared clubs in the league. The Sounders also went on to lift the MLS Cup. 1 / 3 The Galaxy are pretty much exactly in the same position heading into the All-Star Game as Sounders was in 2016. Having lost ten of the first 21 games and sitting in ninth in a weaker Western Conference, the board sacked Curt Onalfo, hired Sigi Schmid, and signed Mexican international attacking midfielder Jonathan dos Santos from Villarreal as a Designated player. Related Post: Orlando City SC: Upstart Lions Stalking and Devouring Their MLS Prey Struggling Orlando City did not sack their manager, but just pulled off the largest trades in MLS history for Dom Dwyer. -

The Best of Soccer Journal: Techniques & Tactics

150 mm 166 mm 166 mm 150 mm Jay Martin (Ed.) The Best of Soccer Journal Journal of Soccer The Best TRAINING EXAMPLE LEARN WHAT TO COACH THE EDITOR The Best of Soccer Journal Warm-up exercises This book offers the experience of the best coaches who have ever Jay Martin, Ph.D. Coaches should be careful during the warm-up phase of practices written for NSCAAs renowned Soccer Journal. Shape your training that players begin with passes that are somewhat shorter than the according to the practical instructions given in this collection. If Techniques + Tactics Martin’s third National length of passes that will occur during the concluding warm-up you want to strengthen the technique and tactics of your team on Coach of the Year award activities. Be certain that your players are warmed up properly and the field, the given training plans will easily provide you with the caps a fairy-tale ending to are stretched sufficiently to prevent injury. knowledge to improve the skills of you players. · the 2011 season. Not only Techniques + Tactics Techniques did his Bishops win their sec- Exercise 1 Based in Kansas City, KS., the NSCAA is the largest soccer coaches’ ond NCAA national title, but Short, short, long passing in groups of five. Begin with players in a organization in the world. Since its founding in 1941, it has grown the victory in the champion- 30 x 30-yard space and expand as needed (Diagram # 1). Player to include more than 30,000 members who coach both genders at ship game gave Martin his receiving the long pass should take a controlling touch and dribble all levels of the sport. -

Ucla World Cup Players 2006

UCLA’S NATIONAL TEAM CONNECTION Snitko competed for the United States in Atlanta, and the 1992 Olympic team UCLA WORLD CUP PLAYERS 2006 ........Carlos Bocanegra included six former Bruins ̶ Friedel, ........................Jimmy Conrad Henderson, Jones, Lapper, Moore and ............................ Eddie Lewis Zak Ibsen ̶ on its roster, the most .............Frankie Hejduk (inj.) from any collegiate institution. Other 2002 ..................Brad Friedel UCLA Olympians include Caligiuri, ...................... Frankie Hejduk .............................. Cobi Jones Krumpe and Vanole (1988) and Jeff ............................ Eddie Lewis Hooker (1984). ......................Joe-Max Moore Several Bruins were instrumental to 1998 ..................Brad Friedel ...................... Frankie Hejduk the United States’ gold medal win .............................. Cobi Jones at the 1991 Pan American Games. ......................Joe-Max Moore Friedel tended goal for the U.S., while 1994 ................Paul Caligiuri Moore nailed the game-winning goal ............................Brad Friedel in overtime in the gold-medal match .............................. Cobi Jones against Mexico. Jones scored one goal ........................... Mike Lapper ......................Joe-Max Moore Bruins Pete Vagenas, Ryan Futagaki, Carlos Bocanegra, Sasha and an assist against Canada. A Bruin- Victorine and Steve Shak (clockwise from top left) won bronze 1990 ................Paul Caligiuri dominated U.S. team won a bronze medals for the U.S. at the 1999 Pan -

PHILADELPHIA UNION V PORTLAND TIMBERS (Sept

PHILADELPHIA UNION v PORTLAND TIMBERS (Sept. 10, PPL Park, 7:30 p.m. ET) 2011 SEASON RECORDS PROBABLE LINEUPS ROSTERS GP W-L-T PTS GF GA PHILADELPHIA UNION Union 26 8-7-11 35 35 30 1 Faryd Mondragon (GK) at home 13 5-1-7 22 19 15 3 Juan Diego Gonzalez (DF) 18 4 Danny Califf (DF) 5 Carlos Valdes (DF) Timbers 26 9-12-5 32 33 41 MacMath 6 Stefani Miglioranzi (MF) on road 12 1-8-3 6 7 22 7 Brian Carroll (MF) 4 5 8 Roger Torres (MF) LEAGUE HEAD-TO-HEAD 25 Califf Valdes 15 9 Sebastien Le Toux (FW) ALL-TIME: 10 Danny Mwanga (FW) Williams G Farfan Timbers 1 win, 1 goal … 7 11 Freddy Adu (MF) Union 0 wins, 0 goals … Ties 0 12 Levi Houapeu (FW) Carroll 13 Kyle Nakazawa (MF) 14 Amobi Okugo (MF) 2011 (MLS): 22 9 15 Gabriel Farfan (MF) 5/6: POR 1, PHI 0 (Danso 71) 11 16 Veljko Paunovic (FW) Mapp Adu Le Toux 17 Keon Daniel (MF) 18 Zac MacMath (GK) 19 Jack McInerney (FW) 16 10 21 Michael Farfan (MF) 22 Justin Mapp (MF) Paunovic Mwanga 23 Ryan Richter (MF) 24 Thorne Holder (GK) 25 Sheanon Williams (DF) UPCOMING MATCHES 15 33 27 Zach Pfeffer (MF) UNION TIMBERS Perlaza Cooper Sat. Sept. 17 Columbus Fri. Sept. 16 New England PORTLAND TIMBERS Fri. Sept. 23 at Sporting KC Wed. Sept. 21 San Jose 1 Troy Perkins (GK) 2 Kevin Goldthwaite (DF) Thu. Sept. 29 D.C. United Sat. Sept. 24 at New York 11 7 4 Mike Chabala (DF) Sun. -

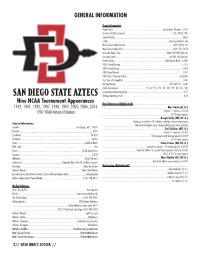

San Diego State Aztecs Starters Returning/Lost

GENERAL INFORMATION Team Information Head Coach ................................................................................. Lev Kirshner (Rutgers, 1991) Record at SDSU (Seasons) .............................................................................138-167-55 (19) Career Record ................................................................................................................Same E-mail .................................................................................................. [email protected] Men’s Soccer Office Phone ............................................................................. (619) 594-0136 Men’s Soccer Office Fax ................................................................................. (619) 594-1674 Associate Head Coach ...........................................................................Matt Hall (20th Season) Assistant Coach ......................................................................................Josh Hill (3rd Season) Home Facility ..................................................................................SDSU Sports Deck (1,250) 2018 Overall Record .................................................................................................... 7-10-1 2018 Home Record ....................................................................................................... 5-5-0 2018 Road Record ........................................................................................................ 2-5-1 2018 Pac-12 Record/Finish ......................................................................................2-8-0/6th -

2011 Nerevolution Mg Sm.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CLUB PAGE YOUTH DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM PAGE Welcome 2 Program Overview 198 2011 Schedule 4 Youth Program Date of Note 198 2011 Quick Facts 5 U.S. Soccer Development Academy 199 Club History 6 SUM Under-17 Cup 199 THE CLUB Gillette Stadium 8 U.S. Soccer Development Academy Clubs 200 Investor/Operators 10 Coaching Staff 201 Executives 12 Academy Alumni 202 Team Staff 14 2011 Schedules 203 Uniform History 17 Under-18 Squad 204 Under-16 Squad 206 2011 REVOLUTION PAGE 2011 Alphabetical Roster 20 MAJOR LEAGUE SOCCER PAGE 2011 Numerical Roster 20 MLS Staff Directory 210 2011 Team TV/Radio Guide 21 MLS Player Rules and Regulations 211 How the Revolution Was Built 22 2010 In Review 215 Head Coach Steve Nicol 23 Chicago Fire 216 Assistant Coaches 24 Chivas USA 218 Team Staff 25 Colorado Rapids 220 Player Profiles 28 Columbus Crew 222 D.C. United 224 TEAM HISTORY PAGE FC Dallas 226 Year-by-Year Results 64 Houston Dynamo 228 2010 In Review 65 LA Galaxy 230 2009 In Review 70 New York Red Bulls 232 2008 In Review 76 Philadelphia Union 234 2007 In Review 82 Real Salt Lake 236 2006 In Review 88 San Jose Earthquakes 238 2005 In Review 94 Seattle Sounders FC 240 2004 In Review 100 Sporting Kansas City 242 2003 In Review 106 Toronto FC 244 2002 In Review 112 Portland Timbers 246 2001 In Review 119 Vancouver Whitecaps 246 2000 In Review 124 2011 Conference Alignments 247 1999 In Review 130 1998 In Review 135 MEDIA INFORMATION PAGE 1997 In Review 140 General Information & Policies 250 1996 In Review 146 Revolution Communications Directory -

Marketing of Professional Women's Soccer in the United States

MARKETING OF PROFESSIONAL WOMEN’S SOCCER IN THE UNITED STATES THROUGH FEMINIST THEORIES by CHRISTOPHER HENDERSON (Under the Direction of James J. Zhang) ABSTRACT Despite the success of the United States Women’s National Team (USWNT), two women’s soccer leagues have quickly failed in the U.S. This doctoral dissertation examines the past and present of the marketing of professional women’s soccer in the United States emphasizing feminist themes to fulfill three objectives: (a) to critically examine the history of the marketing of women’s soccer in the United States to identify and gain a better comprehension of changes in theory and practice of marketing in women’s soccer in the U.S. over time; (b) to identify and explain the use of three feminist themes in the marketing of women’s soccer, specifically in the NWSL; and (c) to analyze the impact of these three feminist themes on the related marketing strategies used within in the NWSL in an effort to build a framework while also developing recommendations for marketing practitioners for the promotion and marketing of professional women’s soccer in the United States. The historical analysis segment revealed that the failure of the first two professional women’s soccer leagues in the United States were largely a result of poor resource allocation and an inability to connect with and retain fans, the media, and sponsors. The Women’s United Soccer Association (WUSA) burned through capital at an unsustainable rate and was unable to maintain the excitement of the 1999 Women’s World Cup, leading to microscopic television ratings and perennially falling attendance. -

Thomas Müller - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Thomas Müller - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Thom... Thomas Müller From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Thomas Müller (German pronunciation: [ˈtʰoː.mas ˈmʏ.lɐ]; Thomas Müller born 13 September 1989) is a German footballer who plays for Bayern Munich and the German national team. Müller plays as a midfielder or forward, and has been deployed in a variety of attacking roles – as an attacking midfielder, second striker, and on either wing. He has been praised for his positioning, team work and stamina, and has shown consistency in scoring and creating goals. A product of Bayern's youth system, he made his first-team breakthrough in the 2009–10 season after Louis van Gaal was appointed as the main coach; he played almost every game as the club won the league and cup double and reached the Champions League final. This accomplishment earned him an international call-up, and at the end of the season he was named in Germany's squad for the 2010 World Cup, where he scored five goals in six appearances Müller with Germany in 2012 as the team finished in third place. He was named as the Personal information Best Young Player of the tournament and won the Golden [1] Boot as the tournament's top scorer, with five goals and Full name Thomas Müller three assists. He also scored Bayern's only goal in the Date of birth 13 September 1989 Champions League final in 2012, with the team eventually Place of birth Weilheim, West Germany losing on penalties. -

A Perfect Script? Manchester United's Class of '92. Journal of Sport And

Citation: Dart, J and McDonald, P (2017) A Perfect Script? Manchester United’s Class of ‘92. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 41 (2). pp. 118-132. ISSN 1552-7638 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723516685272 Link to Leeds Beckett Repository record: https://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/id/eprint/3425/ Document Version: Article (Accepted Version) The aim of the Leeds Beckett Repository is to provide open access to our research, as required by funder policies and permitted by publishers and copyright law. The Leeds Beckett repository holds a wide range of publications, each of which has been checked for copyright and the relevant embargo period has been applied by the Research Services team. We operate on a standard take-down policy. If you are the author or publisher of an output and you would like it removed from the repository, please contact us and we will investigate on a case-by-case basis. Each thesis in the repository has been cleared where necessary by the author for third party copyright. If you would like a thesis to be removed from the repository or believe there is an issue with copyright, please contact us on [email protected] and we will investigate on a case-by-case basis. This is the pre-publication version To cite this article: Dart, J. and McDonald, P. (2016) A Perfect Script? Manchester United’s Class of ’92 Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 1-17 Article first published online: December 23, 2016 To link to this article: DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723516685272 A Perfect Script? Manchester United's Class of ‘92 Abstract The Class of ‘92 is a documentary film which features six Manchester United F.C. -

2011 Boston Breakers Media Guide Alyssa Naeher

BOSbreakers_programAd.pdf 1 4/7/11 3:46 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 2011 BOSTON BREAKERS Schedule Breakers B1 2011 Boston Breakers Contents Team Information: WPS Info: Team History ..........................................4 2009 Statistics....................................43 Front Office........................... ..................6 2010 Statistics....................................45 Breakers Head Coach Bio.....................................7 League Info ........................................47 Assistant Coach Bios............................8 Timeline ..............................................48 Stadium History....................................9 WPS Playoffs ......................................50 Stadium Directions............................10 Tickets & Seating Chart.....................11 Ticket Packages .................................. 12 Kristine Lilly Feature..........................14 Player Info: Roster......................................................16 Jordan Angeli.......................................18 Leah Blayney....................................... 19 Liz Bogus .............................................. 20 Rachel Buehler.....................................21 Lauren Cheney ................................... 22 Stephanie Cox ..................................... 23 Niki Cross...............................................24 Kelsey Davis ......................................... 25 Ifeoma Dieke........................................26 Taryn Hemmings ............................... 27 Amy LePeilbet