MLS As a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World's Game in the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tsg Hoffenheim

DFB-POKAL · VIKTORIA KÖLN · TSG HOFFENHEIM VIKTORIA GEGEN FORTSCHREITENDE IMPFMÜDIGKEIT Wir freuen uns, Sponsor von Viktoria Köln zu sein. Z_ViktoriaKöln1_210x297_2107.indd 1 20.07.2021 17:01:03 INHALT Viktoria, Inhalt Vorwort Wichtige Adressen 3 Eric Bock 4 Realisierung: Herausgeber: Event für treue FC Viktoria Köln 1904 Vorbericht Dauerkarten- Spielbetriebs GmbH Günter-Kuxdorf-Weg 1 TSG Hoffenheim Inhaber 51103 Köln 10 13 Telefon: 02 21 - 84 56 41 94 Telefax: 02 21 - 84 56 45 86 www.viktoria1904.de E-Mail: [email protected] Geschäftsführung: Top Thema: Andreas Rettig, Viktoria mit Patrick Sontheimer Eric Bock & Axel Freisewinkel Impfaktion 15 im Interview 19 Redaktion Frank Bleydorn, Julia Schulz, Jakob Settgast Bilder: © Viktoria Köln, Markus Scheuren, Damals: Als Julia Schulz, Jakob Settgast, Besnik Abazaj, TSG Hoffenheim Viktoria Köln den Präsidium: Neues von FC Union Berlin Günter Pütz, Willy Scheer, der Jugend besiegte Holger Kirsch, Franz Wunderlich 21 27 Layout | Satz | Druck: KölnTotal GmbH Heinrich-Pesch-Straße 7 50739 Köln Telefon: 0221 - 946 946 0 Telefax: 0221 - 946 946 10 Promis bei Finde E-Mail: [email protected] Viktoria den Fehler www.koelntotal.de 37 41 3 VORWORT Liebe Viktorianer*, die Drittliga-Saison hat gerade begonnen. Doch heute Sponsoren und VIP-Gäste. Um in diesem Bereich ein noch steht der DFB-Pokal auf dem Programm. Nachdem wir uns besserer Gastgeber zu sein, haben wir im Vorfeld der Sai- Ende Mai im Bitburger-Pokalfinale in Bonn gegen Aleman- son fleißig daran gearbeitet, unser Hospitality-Angebot nia Aachen durchgesetzt haben, waren wir sehr gespannt, auszubauen. welches Los uns der DFB-Pokal in der 1. Hauptrunde be- scheren würde. -

Messi's Achievements for the 2011-2012 Season

Messi's Achievements for the 2011-2012 Season Individual Records Club (FC Barcelona) 1 The first player to score and assist in every trophy competition (6 in total) in one season. 2 The 2nd club player (after Pedro) to score in 6 official competitions in one season. 3 Leading Barça scorer in Spanish Supacopa with 8 goals. 4 Scored 35 La Liga home goals to set new club and Liga records. 5 With 14 La Liga hat-tricks, sets a new record surpassing César's 13. 6 2nd Barcelona player to win Pichichi twice (shares record with Quini). 7 Converted 10 penalties in La Liga to equal record set by Ronald Koeman (1989-1990). 8 Scored in 10 consecutive Liga games (in which he played) to equal Martin (1942/43) and Ronaldo (1996/97). 9 Equalled record set by Eto'o (2007-08) to score in 7 consecutive La Liga Away games. 10 At age 24, becomes La Liga's youngest player to score 150 goals to set club and Liga records. 11 With 214 games, beats Cocu's record (205 games) to become foreign player with most La Liga games for the club. 12 First player to score 8 hat-tricks in a single La Liga season. 13 15th October 2011: Surpasses Kubala’s 2nd place club record of 194 goals. (With a brace vs. Racing Santander at Camp Nou.) 14 29th October 2011: Scores the club's fastest La Liga hat-trick in 17 minutes (vs. Mallorca at Camp Nou.) 15 19th February 2012: Becomes the club's youngest player to play 200 La Liga games. -

Major League Soccer Atlanta United Vs Philadelphia Union Reddit Live

major league soccer atlanta united vs philadelphia union reddit : liveStream, time GO LIVE http://nufilm.live/event/major-league-soccer-atlanta-united-vs-philadelphia-union-reddit CLICK HERE GO LIVE http://nufilm.live/event/major-league-soccer-atlanta-united-vs-philadelphia-union-reddit 75 votes, 850 comments. FT: Atlanta United FC 2-0 Philadelphia Union Atlanta United FC scorers: Julian Gressel (10'), Josef Martínez (80') Venue … 19' Haris Medunjanin (Philadelphia Union) is shown the yellow card. 19' Second yellow card to Haris Medunjanin (Philadelphia Union). 21' Goal! Atlanta United FC 1, Philadelphia Union 0. Josef Martínez (Atlanta United FC) converts the penalty with a right footed shot to the top left corner. 23' Substitution, Philadelphia Union. Warren Creavalle Atlanta United FC 1, Philadelphia Union 0. Julian Gressel (Atlanta United FC) right footed shot from the centre of the box to the bottom right corner. Assisted by Leandro González Pirez. 33' Goal! Atlanta United FC 2, Philadelphia Union 0. Josef Martínez (Atlanta United FC) left footed shot from the left side of the box to the bottom right Find Atlanta United vs Philadelphia Union result on Yahoo Sports. View full match commentary including video highlights, news, team line-ups, player ratings, stats and more. Major League Soccer 2021 Table. Philadelphia Union are in the 3rd position of Major League Soccer and they are in contention for Final Series Play-offs. Atlanta United are in the 10th position of Major League Soccer. Eastern Conference # Philadelphia have kept a clean sheet in their last 3 away matches (Major League Soccer). Philadelphia win or draw 1.57 Philadelphia win or draw 1.57 Atlanta United is playing against Philadelphia Union in the USA Major League Soccer. -

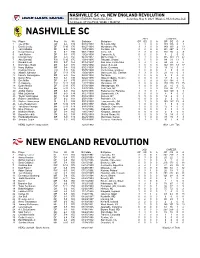

MLS Game Guide

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

Rgv Fc Toros 2021 Information

2021 SEASON GAME NOTES HOME PLAYER2021 SCHEDULE INFO DATE OPPONENT TIME RESULT 05/01 vs. New Mexico United 7:30PM CST W, 1-0 05/06 vs. San Diego Loyal 7:00PM CST W, 1-0 05/16 vs. San Antonio FC 7:30PM CST W, 2-1 05/22 @ El Paso Locomotive FC 8:30PM CST - 05/29 @ San Antonio FC 7:30PM CST - 06/06 @ Miami FC 6:30PM CST - 06/12 vs. Real Monarchs SLC 7:00PM CST - 06/16 vs. Austin Bold FC 7:00PM CST - 0-0-1 06/19 @ San Antonio FC 7:30PM CST - 06/25 vs. Tulsa FC 7:30PM CST - AWAY 06/30 vs. El Paso Locomotive FC 7:00PM CST - 07/10 @ Austin Bold FC 8:00PM CST - 07/17 @ Orange County SC 7:00PM CST - 07/24 vs. Austin Bold FC 8:00PM CST - 07/31 @ Phoenix Rising FC 9:30PM CST - 08/04 @ Real Monarchs SLC 9:00PM CST - 08/08 vs. San Antonio FC 7:30PM CST - 08/14 vs. Colorado Springs Switchbacks FC 7:00PM CST - 08/17 @ Austin Bold FC 8:00PM CST - 08/21 @ El Paso Locomotive FC 8:30PM CST - 08/29 @ OKC Energy FC 5:00PM CST - 3-0-0 09/04 vs. Loudoun United 7:00PM CST - 09/11 @ Colorado Springs Switchbacks FC 8:00PM CST - MATCH INFO 09/18 vs. Colorado Springs Switchbacks FC 7:00PM CST - Saturday, May 22 09/22 @ New Mexico United 8:00PM CST - Southwest University Park 09/25 vs. Atlanta United II 8:00PM CST - 8:30 p.m. -

Live Athletic Bilbao Vs Real Sociedad Online Athletic Bilbao Vs Real Sociedad Stream

Live Athletic Bilbao Vs Real Sociedad Online | Athletic Bilbao Vs Real Sociedad Stream Live Athletic Bilbao Vs Real Sociedad Online | Athletic Bilbao Vs Real Sociedad Stream 1 / 2 Basque Derby Ath Bilbao vs Real Sociedad New Orleans Watch Party. Saved by American Sports Saloon. 1. BilbaoDerbySoccer SeasonSoccer MatchAmerican .... How to watch the Real Sociedad vs Athletic Bilbao live stream video. Predictions, H2H, statistics and live score. La Liga 07/04/2021.. Dec 31, 2020 — Watch Live Stream Online Athletic Bilbao - Real Sociedad (31.12.20). Live Stream Football ... To leave comments, you have to register or login. Apr 28, 2015 — Athletic Bilbao Vs Real Sociedad (La Liga): Live stream, TV channels, Head to Head, Prediction, Lineups, Preview, Watch online, 28 April 2015 .... VsSocre provide live scores, results, predictions ,Head to Head,Lineups and mroe data for this game. Totally, Athletic Bilbao got 14 goals and Real Sociedad got .... Athletic Bilbao vs Real Sociedad live streaming: Watch Copa del Rey Final online, preview and predictions of match on Saturday 3 April 2021. Correct score. Live football, athletics, boxing and more, plus 24-hour news. Still enjoy the series and movies you love. Explore Showmax Pro. Recent Highlights. COSAFA Cup.. Apr 3, 2021 — Venue: Estadio La Cartuja, Seville, Spain. TV Channels: Not available in India Live Streaming: MEGOGO. Which broadcaster shows the final .... Apr 2, 2021 — Athletic Bilbao vs. Real Sociedad: Copa del Rey final live stream, TV channel, how to watch online, news, odds. By Sandra Herrera.. DERBI CLÁSICO | Real Madrid Atlético de Madrid | LaLiga 2003/04. Athletic Bilbao vs. Real Madrid. -

Church Launches Affordable Urban Housing Community

NASCAR Cup Series driver BUBBA WALLACE and Hornets owner MICHAEL JORDAN join forces for historic pairing THE VOICE OF THE BLACK COMMUNITY SINCE 1906 TheThe CharlotteCharlotte PostPost WEEK OF SEPTEMBER 24, 2020 VOLUME 47, NUMBER 3 WWW.THECHARLOTTEPOST.COM $1.50 Lawsuit aims to overturn referenda By Herbert L. White [email protected] The North Carolina NAACP is ap- pealing its case to invalidate two constitutional amendments to the state’s highest court. The civil rights organization will appeal last week’s Court of Ap- peals ruling to overturn a 2019 Su- perior Court decision to block referendums on a voter ID require- ment and lowering the state in- come tax up were illegal because law- makers were elected from illegal racially gerrymandered dis- LAUREL STREET tricts. The NAACP is appealing to the N.C. An artist's rendering of the proposed apartment community at Seventh and Alexander streets. The neighborhood is a collaboration between Little Supreme Court. Wake Rock Community Development Corp. and Charlotte developer Laurel Street. County Superior Spearman Court Judge Bryan Collins declared in February 2019 the amendments were invalid be- Church launches affordable cause they were placed on the 2018 ballot by lawmakers elected in 2016 from racially gerryman- dered districts, which, the NAACP argues, don’t legally represent urban housing community North Carolina voters. Lawmakers elected from the 2016 district maps were ordered by a federal Little Rock AME project to break ground in 2021, open to residents in 2022 court to redraw those boundaries By Herbert L. White Charlotte is also donating vacant land – tle Rock AME Zion’s senior pastor and for the 2018 elections, which Court a former brownfield site – for the project board chair and founder of its CDC. -

2017 United Soccer League Media Guide

Table of Contents LEAGUE ALIGNMENT/IMPORTANT DATES ..............................................................................................4 USL EXECUTIVE BIOS & STAFF ..................................................................................................................6 Bethlehem Steel FC .....................................................................................................................................................................8 Charleston Battery ......................................................................................................................................................................10 Charlotte Independence ............................................................................................................................................................12 Colorado Springs Switchbacks FC .......................................................................................................................................14 FC Cincinnati .................................................................................................................................................................................16 Harrisburg City Islanders ........................................................................................................................................................18 LA Galaxy II ..................................................................................................................................................................................20 -

Relocating to the Greater Charlotte & Lake Norman

RELOCATING TO THE GREATER CHARLOTTE & 1 LAKE NORMAN AREA TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome to Lake Norman, NC! .............................................................................4 Relocation Resources Moving and Storage ............................................................................. 6 Tips for a Stress-Free Moving Experience ........................................... 7 Utilities ................................................................................................. 8 Trash and Recycling .............................................................................. 9 Landscaping and Exterior Home Care .................................................. 9 Home Improvement Stores ................................................................. 10 Garden Centers .................................................................................... 10 Vehicle Registration and License Transfer ........................................... 11 Family Resources Schools ................................................................................................. 12 Hospitals and Medical .......................................................................... 14 Veterinarians ........................................................................................ 15 Pet Sitters & Boarding Facilities ........................................................... 16 Tips For Moving With Pets ................................................................... 17 Preferred Local Real Estate Professionals ...........................................18 -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2021

Part 3 of THE YEAR IN REVIEW pages 7-13 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXXIX No. 5 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JANUARY 31, 2021 $2.00 Ukraine celebrates Unity Day Ukraine’s SBU suspects former agency colonel of plotting to murder one of its generals by Mark Raczkiewycz KYIV – On January 27, the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) said it had secured an arrest warrant for Dmytro Neskoromnyi, a former first deputy head of the agency, on suspicion of conspiring to murder a serving SBU general. Mr. Neskoromnyi, a former SBU colonel, allegedly plotted the assassination with currently serving Col. Yuriy Rasiuk of the SBU’s Alpha anti-terrorist unit. The alleged target was 38-year-old Brig. Gen. Andriy Naumov. Mr. Naumov heads the agency’s internal security department, which is responsible for preventing corruption among the SBU’s ranks. RFE/RL In a news release, the SBU provided video RFE/RL A human chain on January 22 links people along the Paton Bridge in Kyiv over the and audio recordings, as well as pictures, as Security Service of Ukraine Brig. Gen. Dnipro River that bisects the Ukrainian capital, symbolizing both sides uniting when evidence of the alleged plot. The former col- Andriy Naumov the Ukrainian National Republic was formed in 1919. onel was allegedly in the process of paying “If there is a crime, we must act on it. $50,000 for carrying out the murder plot. by Roman Tymotsko (UPR), Mykhailo Hrushevskyy. And, in this case, the SBU worked to pre- Mr. -

Bullock Paper.Pdf (1.7MB)

MAXIMIZING COMMUNITY-BASED DEVELOPMENT OUTCOMES: THE CASE OF RALEIGH’S DOWNTOWN SOUTH PROPOSAL Caylin Bullock A capstone thesis paper submitted to the Faculty Director of the Urban & Regional Planning Program at Georgetown University’s School of Continuing Studies in fulfillment of the requirements for Masters of Professional Studies in Urban & Regional Planning. Project Advisor: Michael Stevens, AICP Academic Advisor: Uwe S. Brandes © Copyright 2019 by Caylin Bullock All Rights Reserved 1 ABSTRACT This paper explores a proposed large mixed-use development project in Raleigh, North Carolina as a case study to identify potential linkages between privately conceived urban development, community benefits, and the corresponding roles played by the private sector, municipalities and community stakeholders. Following a literature review and review of case study precedent practices, research was conducted through unstructured interviews with public and private stakeholders in Raleigh and analysis of project-based scenarios. This paper argues that when receiving proposals, cities must embrace partnerships to maximize positive community-based development outcomes. KEYWORDS Community Benefit Agreement (CBA), Equitable Development, Development Agreement, Public-Private Partnerships, Stadium Development, Raleigh, North Carolina RESEARCH QUESTIONS What are national best practices in the finance and development of large-scale mixed-use urban development projects comparable to the Downtown South proposal? In the case of Raleigh, how might the municipality more aggressively position its actions to ensure long-term equitable development outcomes for historically underserved community stakeholders in close proximity to the project? How might Raleigh institutionalize a project-based agreement as a binding and durable governance structure for future development projects? 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... -

1 BEFORE the UNITED STATES OLYMPIC COMMITTEE Hope Solo, Claimant Vs. United States Soccer Federation, Inc., Respondent COMPLAIN

BEFORE THE UNITED STATES OLYMPIC COMMITTEE Hope Solo, Claimant vs. United States Soccer Federation, Inc., Respondent COMPLAINT UNDER SECTION 220527 OF THE TED STEVENS ACT I. INTRODUCTION 1. Pursuant to the Ted Stevens Olympic and Amateur Sports Act1 (the “Stevens Act”), the United States Olympic Committee (“USOC”) has recognized the United States Soccer Federation (“USSF” or the “Federation”) as the National Governing Body (“NGB”) for the sport of soccer in the United States. This Complaint is being filed because the USSF has become blinded to its fundamental obligation as an NGB to “develop interest and participation throughout the United States and be responsible to the persons and amateur sports organizations it represents.”2 Instead, because of the power, prestige, status and money flowing from the Federation’s alliance with Major League Soccer, a professional men’s league (the “MLS”), and its affiliate, Soccer United Marketing, LLC (“SUM”), the USSF’s paramount concern has become protecting and nurturing the MLS, even if at the expense of other stakeholders, including those involved in professional women’s and amateur soccer. 1 36 U.S.C. § 220501 et seq. 2 Id. § 220524(1). 1 2. Because of its institutional bias in favor of MLS and commercial partnership with SUM, the Federation now appears to believe that its effectiveness should be judged not by how well amateur, youth, women’s and non-MLS men’s professional soccer are doing, but how well MLS is performing and how much money the Federation’s partnership with SUM is generating. Some Federation officials believe they are doing a good job because the entry fee MLS charges new teams keeps increasing even though not a penny of that money goes to the Federation or its non-MLS stakeholders.