Race and Recreation in Charlotte, North Carolina, 1927-1973

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Church Launches Affordable Urban Housing Community

NASCAR Cup Series driver BUBBA WALLACE and Hornets owner MICHAEL JORDAN join forces for historic pairing THE VOICE OF THE BLACK COMMUNITY SINCE 1906 TheThe CharlotteCharlotte PostPost WEEK OF SEPTEMBER 24, 2020 VOLUME 47, NUMBER 3 WWW.THECHARLOTTEPOST.COM $1.50 Lawsuit aims to overturn referenda By Herbert L. White [email protected] The North Carolina NAACP is ap- pealing its case to invalidate two constitutional amendments to the state’s highest court. The civil rights organization will appeal last week’s Court of Ap- peals ruling to overturn a 2019 Su- perior Court decision to block referendums on a voter ID require- ment and lowering the state in- come tax up were illegal because law- makers were elected from illegal racially gerrymandered dis- LAUREL STREET tricts. The NAACP is appealing to the N.C. An artist's rendering of the proposed apartment community at Seventh and Alexander streets. The neighborhood is a collaboration between Little Supreme Court. Wake Rock Community Development Corp. and Charlotte developer Laurel Street. County Superior Spearman Court Judge Bryan Collins declared in February 2019 the amendments were invalid be- Church launches affordable cause they were placed on the 2018 ballot by lawmakers elected in 2016 from racially gerryman- dered districts, which, the NAACP argues, don’t legally represent urban housing community North Carolina voters. Lawmakers elected from the 2016 district maps were ordered by a federal Little Rock AME project to break ground in 2021, open to residents in 2022 court to redraw those boundaries By Herbert L. White Charlotte is also donating vacant land – tle Rock AME Zion’s senior pastor and for the 2018 elections, which Court a former brownfield site – for the project board chair and founder of its CDC. -

Relocating to the Greater Charlotte & Lake Norman

RELOCATING TO THE GREATER CHARLOTTE & 1 LAKE NORMAN AREA TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome to Lake Norman, NC! .............................................................................4 Relocation Resources Moving and Storage ............................................................................. 6 Tips for a Stress-Free Moving Experience ........................................... 7 Utilities ................................................................................................. 8 Trash and Recycling .............................................................................. 9 Landscaping and Exterior Home Care .................................................. 9 Home Improvement Stores ................................................................. 10 Garden Centers .................................................................................... 10 Vehicle Registration and License Transfer ........................................... 11 Family Resources Schools ................................................................................................. 12 Hospitals and Medical .......................................................................... 14 Veterinarians ........................................................................................ 15 Pet Sitters & Boarding Facilities ........................................................... 16 Tips For Moving With Pets ................................................................... 17 Preferred Local Real Estate Professionals ...........................................18 -

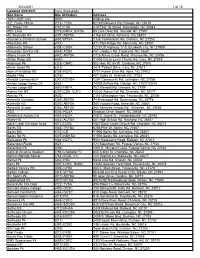

REEL INDEX (Charlotte Observers Clippings Microfilm)

1 CHARLOTTE OBSERVER CLIPPINGS FILE REEL INDEX REEL 1 (BOX 1) Babies – Jan. 1958 – Dec. 1970 Ballots - Election – July 1958 – Nov. 1970 Bank Robberies (General [& some U.S.]) – Apr. 1952 – Dec. 1969 (list of people committing robbery, time to be served, etc. from Apr. 1952 - July 1957 – then clippings start with Aug. 1958) Bank Robberies Charlotte – Aug. 1958 – Nov. 1969 Bank Robberies, N. C. – May 1956 – Dec. 1969 Bank Robberies, S. C. – July 1958 – Dec. 1969 Banking – Dec. 1956 – Dec. 1969 Elections, Primary & Regular Data – May 1958 – Dec. 1969 Elections North Carolina – May 1952 – Dec. 1970 (repeat of subject card with 1960) Election Presidential – Oct. 1956 – Dec. 1970 Elections Charlotte Municipal – Apr. 1943 – Nov. 1969 Elections Mecklenburg County – Feb. 1958 – Nov. 1969 Elections Mecklenburg State House of Representatives – Apr. 1960 – Dec. 1969 Elections - Mecklenburg State Senator – Feb. 1957 – Dec. 1969 Elections, Mecklenburg Precincts & Registrars – Oct. 1948 – Nov. 1969 Duke Power Co. – Oct. 1956 – Dec. 1969 REEL 2 (BOX 2) Charlotte Area Fund – Aug. 1963 – Dec. 1969 Charlotte City Council – Oct. 1944 – Dec. 1969 Duke Power Co. – Feb. 1963 (one clipping only – no subject announcement) Vietnam Negotiations – May 1967 – Dec. 1969 Park and Recreation Commission – Aug. 1942 – Dec. 1969 Charlotte City Parks – Apr. 1956 – Dec. 1969 Freedom Park – Aug. 1944 – May 1968 Charlotte Public Library Park - Mar. 1956 - May 1968 (now known as Arequipa Park - Nov. 1971) REEL 3 (BOX 3) Schools, Charlotte Mecklenburg School Systems – Dec. 1947 – Dec. 1969 Charlotte Police Dept. – Jan. 1950 – Dec. 1969 Charlotte Mecklenburg Board of Education (Sessions Laws) 1959 (Merger of City and County Systems) (Reprint of H. -

LSTA Grant Lesson Plan Writing Cohort Submitted by Rebecca Griffith, Isaac Bear Early College High School

William Madison Randall Library LSTA Grant Lesson Plan Writing Cohort Submitted by Rebecca Griffith, Isaac Bear Early College High School Overview Abstract Examine the work performed by the women and teenagers of the Women’s Good Will Committee of High Point, North Carolina as they labor to bridge race relations in their community. Explore primary source documents using close reading strategies. Discover how the work of the High Point Women’s Good Will Committee serves as a positive model for other groups to replicate. Extrapolate and apply the work of the High Point Women’s Good Will Committee to a current societal ill and seek areas in which adults and students can cooperatively find solutions to these problems. Standards AH2.H.4 – Analyze how conflict and compromise have shaped politics, economics and culture in the United States. AH2.H.5 – Understand how tensions between freedom, equality and power have shaped the political, economic and social development of the United States. AH2.H.7 – Understand the impact of war on American politics, economics, society and culture. Objectives AH2.H.4.1 – Analyze the political issues and conflicts that impacted the United States since Reconstruction and the compromises that resulted (e.g., Populism, Progressivism, working conditions and labor unrest, New Deal, Wilmington Race Riots, Eugenics, Civil Rights Movement, Anti-War protests, Watergate, etc.). AH2.H.4.3 – Analyze the social and religious conflicts, movements and reforms that impacted the United States since Reconstruction in terms of participants, strategies, opposition, and results (e.g., Prohibition, Social Darwinism, Eugenics, civil rights, anti-war protest, etc.). -

8/24/2021 1 of 14 Updated 8/24/2021 (Xxx) Three-Digits Site Name Site Id/Club(S) Address TBA (USSF-NC) (000) Holding Site A.E. F

9/24/2021 1 of 15 Updated 9/24/2021 (xxx) three-digits Site Name Site id/Club(s) Address TBA (USSF-NC) (000) holding site A.E. Finley YMCA (716) TYSC 9216 Baileywick Rd, Raleigh, NC 27615 A.L.Brown HS (752) CSA 415 East 1st Street, Kannapolis, NC 28083 ABC Land (776) NRFA, EWSA 65 Liles Dean Rd, Wendell NC 27591 AC Reynolds HS (001) ABYSA 1 Rocket Drive, Asheville, NC 28803 Alamance Christian School (693) MYSA 1336 Townbranch Rd, Graham, NC 27253 Albemarle HS (747) 311 Park Ridge Rd, Albemarle, NC 28001 Albemarle School (334) CUSA 1210 US Highway 17 S, Elizabeth City, NC 27909 Alexander Central HS (524) ACSA 161 Liledoun Rd, Taylorville, NC 28681 Allens Creek Pk (442) ABYSA 1725 Allens Creek Road, Waynesville, NC 28786 Alston Ridge ES (630) 11555 Green Level Church Rd, Cary, NC 27519 Anderson Pk (328) CHAC 302 Hwy NC 54 W, Carrboro, NC 27510 Annie Jones Pk (315) 1414 Tarbert Drive, Cary, NC 27511 Apex Friendship MS (734) NCFC 7701 Humie Olive Rd, Apex, NC 27502 Apollo Field (248) 401 Goley St, Graham, NC 27253 Arcadia Community F (342) DCYSA 1291 Community Rd, Lexington, NC 27295 Archer Lodge Comm Ctr (681) 14009 Buffalo Rd, Clayton, NC 27527+D476 Archer Lodge MS (680) NRFA 762 Wendell Rd, Wendell, NC 27591 Ardrey Kell HS (257) CSA, CUFC 10220 Ardrey Kell Rd, Charlotte, NC 28277 Arnette Pk (602) 2165 Wilmington Hwy, Fayetteville, NC 28306 Asheville Christian (265) ABYSA 74 Riverwood Rd, Swannanoa, NC 28778 Asheville HS (003) ABYSA 340 Victoria Road, Asheville, NC 28801 Asheville School (263) ABYSA 360 Asheville School Rd, Asheville, NC 28806 ASU (004) HCSA Stadium Drive, Boone, NC 28608 Athletics & Activity Ctr (553) HCSA 708 S. -

Page 1 MEET CHARLOTTE MEET CHARLOTTE

EXPERIENCEMEET THE MOMENTUM MEET CHARLOTTE CHARLOTTE SEE WHY MAJOR COMPANIES TAP INTO CHARLOTTE’S ENERGY TO ESTABLISH NEW HQS. MOMENTUM. Charlotte teems with activity. This is a city that is luring new residents by the day and major new corporate headquarters practically by the month. Why is Charlotte such a kinetic environment? The pillars of talent to propel healthy businesses, low cost of living to attract young workers, ENERGY. proactive city government to encourage innovative companies, and an environment that appeals to weekend adventurers and new families alike. CHARLOTTEIt’s a city that works hard and plays well, with a booming corporate IS landscape that welcomes newcomers and makes them feel as if they’re DYNAMICPOSITIVITY. being ushered into an inclusive and highly desirable community. 02 06 INDUSTRIES 05 HEADQUARTERS & HISTORY 07 COMMERCE IN CHARLOTTE 09 TALENT & AFFORDABILITY 10 INNOVATION 11 EDUCATION & JOBS 12 UNIVERSITIES 14 CHARLOTTE LIVING 13 CHARLOTTECOMMUNITY-DRIVEN & WORLDIS CLASS 16 CHARLOTTE CULTURE 19 PUTTING CHARLOTTE 17 TRANSPORTATION & INFRASTRUCTURE BUSINESSES ON THE MAP TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE 21 RESILIENCE & RESOLVE 22 COMMUNITY RESPONSE DYNAMIC23 MOMENTUM & VISION 25 CONTACT US 04 CHARLOTTE’S HERITAGE TARGET INDUSTRIES TARGET OPERATIONS FUELS ITS MOMENTUM A CITY OF INDUSTRY The office buildings and warehouses of Charlotte bustle Charlotte is a city built on commerce. Growing healthy, groundbreaking businesses FINANCE HEADQUARTERS with activity. Buttoned-down bankers collaborate with is at the core of Charlotte’s DNA. The energy that flows through Charlotte’s business freewheeling fintech experts changing the future of community starts with its students and young workforce and continues up to C-Suites. -

MLS As a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World's Game in the U.S

MLS as a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World’s Game in the U.S. Stephen A. Greyser Kenneth Cortsen Working Paper 21-111 MLS as a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World’s Game in the U.S. Stephen A. Greyser Harvard Business School Kenneth Cortsen University College of Northern Denmark (UCN) Working Paper 21-111 Copyright © 2021 by Stephen A. Greyser and Kenneth Cortsen. Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Funding for this research was provided in part by Harvard Business School. MLS as a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World’s Game in the U.S. April 8, 2021 Abstract The purpose of this Working Paper is to analyze how soccer at the professional level in the U.S., with Major League Soccer as a focal point, has developed over the span of a quarter of a century. It is worthwhile to examine the growth of MLS from its first game in 1996 to where the league currently stands as a business as it moves past its 25th anniversary. The 1994 World Cup (held in the U.S.) and the subsequent implementation of MLS as a U.S. professional league exerted a major positive influence on soccer participation and fandom in the U.S. Consequently, more importance was placed on soccer in the country’s culture. The research reported here explores the league’s evolution and development through the cohesion existing between its sporting and business development, as well as its performance. -

Subject: (Cointelpro) White Hate Groups Sub 8 Section 2 157-9

FREEDOM OF INFORMATION AND PRIVACY ACTS SUBJECT: (COINTELPRO) WHITE HATE GROUPS SUB 8 SECTION 2 157-9 FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION NOTICE THE BEST COPIES OBTAINABLE ARE INCLUDED IN THE REPRODUCTION OF THE FILE. PAGES INCLUDED THAT ARE BLURRED, LIGHT OR OTHERWISE DIFFICULT TO READ ARE THE RESULT OF THE CONDITION AND OR COLOR OF THE ORIGINALS PROVIDED. THESE ARE THE BEST COPIES AVAILABLE. * V! Maetr WS (187 -8) - ar r 1 - tr. Memie ~-C -w - L The~ 1*1/6 1. tL "3am ad Okewa - a...papr atltlltta genera earth Crettas, Erte asettl ass er t N r a ta sr na - easte - ale sw ntli ~~to as sale thelL use*II fis **** **r( J~n as mura me-- wa sees: S4to a -an Elma M '.1,- lan;cKr~ a .~~r gkr .....sa poem tr ** ammes as rseasest as i aders Mtes Sma anMe etso eaisas waths sinsuelistatiimes3Ld gmas .. wi /m rn tam set-tr*9**-5 orsrlasse - -af- - cine. ... c.....s asIo OCT 20O196 Comedd .. .. 0... 1 96 6- - ca L,QO nO p un FD-350 (Rev. 7-16-43) , - r. DeLoe Mr. Mohr_ SMr. Wick. Mr. Casper- Mr. Callahan_ Mr. Conrad. (Mount Clipping in Space Below) Mr. FePt. Mr. Gaii __ Mr. Roe Mr. Sullivan Mr. Tavd Mr. Trottar Tdele. Room Kis H-dxet Mis Gandy (Indicate poqe, naes of newpaper, city and *tate.) 16 NEWS AND OBSRVE - Raleigh, N.C. -I af ssA merw Editor: Ttle: Character: or sficatio n: * Submittlnq Office: CE Being Investigated F -36 iRev. 5-22-64) 9 FBI Date: 10/14/66 Transmit the baliwing in ' ,(Tpe in plainlext or code I via AIRiL (Priorit)) ----- ------ -------------------------------------------- - DIRECTOR, FBI (157-9-8) - SAC, CRARLOTTE (157-281) COETERTMI.TGENCE pnoanu INTERNAL SECURITY - - DIS8RUKPrIO ReBulet, 9/29/66. -

OBJ (Application/Pdf)

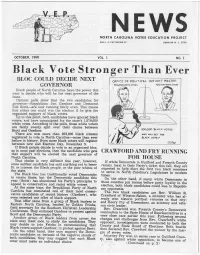

NEWS NORTH CAROLINA VOTER EDUCATION PROJECT 336'A E. PETTIGREW ST. DURHAM, Cl . C.27701 OCTOBER, 1968 VOL 1 NO. 1 Black Vote Stronger Than Ever BLOC COULD DECIDE NEXT GOVERNOR Black people of North Carolina have the power this year to decide who will be the next governor of the state. Opinion polls show that the two candidates for governor—Republican Jim Gardner and Democrat Bob Scott—are now running fairly even. This means that either one could win the election if he gets the organized support of black voters. Up to this point, both candidates have ignored black voters, and have campaigned for the state's 1,579,000 white votes. According to the polls, these white voters are fairly evenly 5pl.it over their choice 'between Scott and Gardner. There are now more than 303,000 black citizens registered to vote in North Carolina—more than ever before in history. Even more black voters will register between now and Election Day, November 5. If Black people decide to vote in an organized bloc, as in most past elections, then the candidate who gets that support will be elected the next governor of CRAWFORD AND FRY RUNNING North Carolina. FOR HOUSE ' rl .C 'a If white Democrats in Guilford and Forsyth County since neither candidate has said anything yet to bene remain loyal to their Party's ticket this fall, they are fit or interest the Black people, or the poor whites of expected to help elect the first two black members the state. to serve in North Carolina's Legislature in modern The Black bloc has traditionally voted Democratic times. -

Charles H. Baker Partner

Charles H. Baker Partner New York D: +1-212-326-2121 [email protected] Charles Baker is Co-Chair of O’Melveny’s Sports Industry Group. Admissions Chuck’s corporate practice encompasses mergers and acquisitions, private equity, and venture capital transactions, with Bar Admissions a core focus in the sports, media and consumer sectors. New York Chuck has represented buyers and sellers of sports franchises in the National Football League, National Basketball Association, Education National Hockey League, Major League Baseball, Major League Cornell University, J.D. Soccer, National Women’s Soccer League and many of the European football leagues. Recently, Chuck represented David Tepper, founder and president of global hedge fund Appaloosa Management, in his acquisition of the NFL’s Carolina Panthers and Charlotte FC, MLS’s 30th expansion team. Chuck has been featured by dozens of national publications and other media outlets as a thought leader in the fields of sports and entertainment law, and is also a frequent public speaker on those topics. Most recently, Law360 named Chuck to its 2020 list of Sports & Betting MVPs. The American Lawyer named Chuck to its prestigious 2019 “Dealmakers of the Year” list and he was also profiled in Variety’s 2018 and 2017 “Dealmakers Elite New York,” a feature spotlighting the most important players in the fields of law, finance, representation, and executive leadership. Chuck has been recognized nationally for sports law in the last six editions of Chambers USA: America’s Leading Lawyers for Business, which has described him as a “very strong practitioner” who is “well connected, incredibly bright and just able to get the deal closed” with “tremendous experience and know-how in the sports space.” O’Melveny & Myers LLP 1 He was also recognized by Law360 in 2015 and 2016 for his stellar M&A and sports law work, and by the Global M&A Network for his work on the sale of the Atlanta Hawks NBA team, naming it the “2015 USA Deal of the Year” at its prestigious M&A Atlas Awards. -

National Football League

NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE {Appendix 3, to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 21} Research completed as of August 7th, 2020 Team: Arizona Cardinals Principal Owner: Michael Bidwell Year Established: 1898 Team Website Twitter: @AZCardinals Most Recent Purchase Price ($/Mil): $.05 (1932) Current Value ($/Mil): $2.25 B Percent Change From Last Year: 5% Stadium: State Farm Stadium Date Built: 2006 Facility Cost ($/Mil): $455 Percentage of Stadium Publicly Financed: 76% Facility Financing: The Arizona Sports & Tourism Authority, a public entity, contributed $300.4 million, most of which came from a 1% hotel/motel tax, a 3.25% car rental tax, and a stadium- related sales tax. The Arizona Cardinals contributed $145.4 million. Glendale contributed $9.9 million. The Cardinals purchased the land for the stadium for $18.5 million. Facility Website Twitter: @StateFarmStdm UPADTE: In October 2019, President Michael Bidwell became Chairman after longtime Arizona Cardinals owner William Bidwell passed away at the age of 88. State Farm Stadium is set to host Super Bowl LVII in 2023 and the NCAA men’s basketball Final Four in 2024. NAMING RIGHTS: In 2018, the Cardinals Stadium reached an 18-year naming rights agreement with State Farm Insurance. Due to a confidentiality agreement, team owner Bidwill declined to state to the public the value of the new naming rights deal with State Farm. Sports Business Daily reported that the University of Phoenix was paying between $8-$9 million a year for the previous naming rights deal before State Farm Insurance obtained -

2021-22 Charlotte Athletics Almanac

2021-22 CHARLOTTE ATHLETICS ALMANAC ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: This almanac is designed to provide a quick reference into the histories of the Charlotte 49ers athletic program, an athletic department which sponsors 18 NCAA Division I sports entering the 2021-22 academic year. More comprehensive information on each sport can be found linked on Charlotte49ers.com. CREDITS: Lead Editor: Travis Woods Assistant Editors: Tom Whitestone, Sean Fox, past media relations personnel GENERAL INFORMATION Location .........................Charlotte, NC 28223 Founded ....................................................... 1946 Enrollment ................................................30,146 Nickname ....................................................49ers Colors ......................................Green and White NCAA Affiliation ...................................Division I Conference ............................ Conference USA Chancellor ............................ Dr. Sharon Gaber Athletics Director .................................Mike Hill OVERVIEW SOCIAL MEDIA The Charlotte 49ers are UNC Charlotte's NCAA Division I athletic program. Members of Con- ference USA, the Charlotte 49ers boast 18 NCAA sports. Male sports are baseball, basketball, INFORMATION cross country, football, golf, soccer, tennis, indoor track and field and outdoor track and field. Female sports are basketball, cross country, golf, soccer, softball, tennis, indoor track Website ...................www.charlotte49ers.com Twitter ........................................Charlotte49ers