Bullock Paper.Pdf (1.7MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tax Increment Financing and Major League Venues

Tax Increment Financing and Major League Venues by Robert P.E. Sroka A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sport Management) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Judith Grant Long, Chair Professor Sherman Clark Professor Richard Norton Professor Stefan Szymanski Robert P.E. Sroka [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6310-4016 © Robert P.E. Sroka 2020 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, John Sroka and Marie Sroka, as well as George, Lucy, and Ricky. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my parents, John and Marie Sroka, for their love and support. Thank you to my advisor, Judith Grant Long, and my committee members (Sherman Clark, Richard Norton, and Stefan Szymanski) for their guidance, support, and service. This dissertation was funded in part by the Government of Canada through a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Doctoral Fellowship, by the Institute for Human Studies PhD Fellowship, and by the Charles Koch Foundation Dissertation Grant. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES v LIST OF FIGURES vii ABSTRACT viii CHAPTER 1. Introduction 1 2. Literature and Theory Review 20 3. Venue TIF Use Inventory 100 4. A Survey and Discussion of TIF Statutes and Major League Venues 181 5. TIF, But-for, and Developer Capture in the Dallas Arena District 234 6. Does the Arena Matter? Comparing Redevelopment Outcomes in 274 Central Dallas TIF Districts 7. Louisville’s KFC Yum! Center, Sales Tax Increment Financing, and 305 Megaproject Underperformance 8. A Hot-N-Ready Disappointment: Little Caesars Arena and 339 The District Detroit 9. -

MLS As a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World's Game in the U.S

MLS as a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World’s Game in the U.S. Stephen A. Greyser Kenneth Cortsen Working Paper 21-111 MLS as a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World’s Game in the U.S. Stephen A. Greyser Harvard Business School Kenneth Cortsen University College of Northern Denmark (UCN) Working Paper 21-111 Copyright © 2021 by Stephen A. Greyser and Kenneth Cortsen. Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Funding for this research was provided in part by Harvard Business School. MLS as a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World’s Game in the U.S. April 8, 2021 Abstract The purpose of this Working Paper is to analyze how soccer at the professional level in the U.S., with Major League Soccer as a focal point, has developed over the span of a quarter of a century. It is worthwhile to examine the growth of MLS from its first game in 1996 to where the league currently stands as a business as it moves past its 25th anniversary. The 1994 World Cup (held in the U.S.) and the subsequent implementation of MLS as a U.S. professional league exerted a major positive influence on soccer participation and fandom in the U.S. Consequently, more importance was placed on soccer in the country’s culture. The research reported here explores the league’s evolution and development through the cohesion existing between its sporting and business development, as well as its performance. -

D.C. United Opens a New Era at Audi Field When the Calendar Page Turns to Closer to Their Fan Base

AUDI FIELD OPENING I HOME OF D.C. UNITED D.C. UNITED WELCOMES A NEW ERA OF SOCCER WITH THE OPENING OF AUDI FIELD For 22 years, D.C. United, one of the original 10 teams in Major League Soccer, has played its home games at the 57-year-old, 45,000-seat RFK Stadium. Although packed with history, the cavernous building did not give the Black-and-Red much of a home field advantage. For more than 10 years, D.C. United tried to secure a new home pitch. The team’s dream of a new home will become a reality on July 14 when they move into the 20,000-seat, soccer-specific Audi Field. From its innovative technology to its location in southwest Washington in the redeveloped Buzzard Point, Audi Field will capture the nation’s interest when it opens to a sold-out crowd. D.C. United Opens a New Era at Audi Field When the calendar page turns to closer to their fan base. The owners wanted to be in south- “We’re in a dynamic neighborhood July 14, the dream of D.C. United “We’re particularly attractive to the west Washington, where the heart and in Buzzard Point, which is a fast-grow- owners Erick Thohir and Jason Levien millennial and Generation Z crowd soul of the city is moving. They found ing, exciting area in downtown Wash- will become a reality. On that long- because of the fast-paced nature of that spot at Buzzard Point, between ington,” said Levien. awaited day, D.C. -

17 Sports Halls of Fame & Museums

17 SPORTS HALLS OF FAME & MUSEUMS 17.1 Overview There are approximately 80 national sports museums and halls of fame in North America, in addition to dozens of team and local sports museums. 17.2 Largest Halls of Fame The following are recent attendance estimates for the largest sports halls of fame: • National Baseball Hall of Fame (Cooperstown, NY): 350,000 • Hockey Hall of Fame (Toronto, Ontario, Canada): 300,000 • NASCAR Hall of Fame (Charlotte, NC): 260,000 • College Football Hall of Fame (Atlanta, GA): 250,000 • Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame (Springfield, MA): 200,000 • World Golf Hall of Fame (St. Augustine, FL): 210,000 • Pro Football Hall of Fame (Canton, OH): 200,000 Revenue at major sports halls of fame are as follows (source: SportsBusiness Journal): • Pro Football Hall of Fame (Canton, OH): $17.0 million • Hockey Hall of Fame (Toronto, Ontario, Canada): $13.1 million • National Baseball Hall of Fame (Cooperstown, NY): $ 8.3 million • International Tennis Hall of Fame (Newport, RI): $ 6.9 million • Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame (Springfield, MA): $ 6.2 million 17.3 List Of Sports Museums The following is a list of U.S. and Canadian sports museums and halls of fame (team and local museums are excluded): • Alabama Sports Hall of Fame (Birmingham, AL; www.ashof.org) • Archery Hall of Fame and Museum (Union City, PA; www.archeryhalloffame.org) • Babe Ruth Birthplace & Museum (Baltimore, MD; http://baberuthmuseum.org) • Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame (San Francisco, CA; www.bashof.org) • California Surf Museum -

REFLECTIONS Washington’S Southeast / Southwest Waterfront

REFLECTIONS Washington’s Southeast / Southwest Waterfront CAMBRIA HOTEL Washington, DC Capitol Riverfront REFLECTIONS Washington’s Southeast / Southwest Waterfront Copyright © 2021 by Square 656 Owner, LLC Front cover image: Rendering of the Frederick Douglass Memorial ISBN: 978-0-578-82670-7 Bridge. The bridge connects the two shores of Designed by LaserCom Design, Berkeley CA the Anacostia River and is named after a former slave and human rights leader who became one of Washington’s most famous residents. District Department of Transportation vi FOREWORD REFLECTIONS Washington’s Southeast / Southwest Waterfront Marjorie Lightman, PhD William Zeisel, PhD CAMBRIA HOTEL Washington, DC Capitol Riverfront QED Associates LLC Washington, DC CAMBRIA HOTEL n REFLECTIONS vii Then ... A gardener’s residence on the site of the Cambria Hotel. The flat-roofed frame house, 18 feet wide and costing $1,800 to construct more than a century ago, was home to Samuel Howison, a market gardener. The cornice at the top of the building now graces the Cambria Hotel’s lobby, and a fireplace mantle accents the rooftop bar. Peter Sefton Now ... The Cambria Hotel at 69 Q Street SW, a part of the Southeast/Southwest waterfront’s renaissance. Donohoe Welcome to the Cambria Hotel Located in an historic part of one of the world’s great cities. ashington is a star-studded town where money and influence glitter on a world stage of W24/7 news bites. Images of the White House, the Capitol, and the Mall are recognized around the world as synonymous with majesty and power. Washington, the nation’s capital, shapes our times and history. -

MLS Game Guide

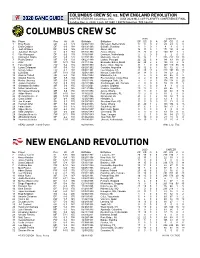

COLUMBUS CREW SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION MAPFRE STADIUM, Columbus, Ohio AUDI 2020 MLS CUP PLAYOFFS CONFERENCE FINAL Sunday, Dec. 6, 2020, 3 p.m. ET (ABC / ESPN Deportes, TVA Sports) COLUMBUS CREW SC 2020 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Eloy Room GK 6-3 179 02/06/1989 Nijmegen, Netherlands 17 17 0 0 29 29 0 0 2 Chris Cadden DF 6-0 168 09/19/1996 Bellshill, Scotland 8 3 0 1 8 3 0 1 3 Josh Williams DF 6-2 185 04/18/1988 Akron, OH 12 11 0 1 174 154 9 6 4 Jonathan Mensah DF 6-2 183 07/13/1990 Accra, Ghana 23 23 0 0 100 97 3 1 5 Vito Wormgoor DF 6-2 179 11/16/1988 Leersum, Netherlands 2 2 0 0 2 2 0 0 6 Darlington Nagbe MF 5-9 170 07/19/1990 Monrovia, Liberia 15 14 1 1 285 272 30 38 7 Pedro Santos MF 5-6 139 04/22/1988 Lisbon, Portugal 22 22 6 8 94 89 18 23 8 Artur MF 5-11 154 03/11/1996 Brumado, Bahia, Brazil 22 20 2 4 108 99 2 9 9 Fanendo Adi FW 6-4 185 10/10/1990 Benue State, Nigeria 11 1 0 0 149 110 55 14 10 Lucas Zelarayan MF 5-9 154 06/20/1992 Cordoba, Argentina 16 12 6 4 16 12 6 4 11 Gyasi Zardes FW 6-1 187 09/02/1991 Los Angeles, CA 21 20 12 4 213 197 78 23 12 Luis Diaz MF 5-11 159 12/06/1998 Nicoya, Costa Rica 21 14 0 3 34 23 2 7 13 Andrew Tarbell GK 6-3 194 10/07/1993 Mandeville, LA 7 6 0 0 48 46 0 0 14 Waylon Francis DF 5-9 160 09/20/1990 Puerto Limon, Costa Rica 4 2 0 0 115 98 0 19 16 Hector Jimenez MF 5-9 145 11/03/1988 Huntington Park, CA 8 4 0 1 176 118 6 25 17 Jordan Hamilton FW 6-0 185 03/17/1996 Scarborough, ON, Canada 2 0 0 0 59 28 11 3 18 Sebastian Berhalter MF 5-9 155 05/10/2001 London, England 9 4 0 0 9 4 0 0 19 Milton Valenzuela DF 5-6 145 08/13/1998 Rosario, Argentina 19 17 0 3 49 46 1 9 20 Emmanuel Boateng MF 5-6 150 01/17/1994 Accra, Ghana 10 3 0 1 121 68 9 14 21 Aidan Morris MF 5-10 158 11/16/2001 Fort Lauderdale, FL 10 2 0 0 10 2 0 0 22 Derrick Etienne Jr. -

Washington DC Emerging Corridors + Opportunity Zones

EMERGING CORRIDORS + OPPORTUNITY ZONES 2020 EDITION In Public-Private Partnership with IMAGE COURTESY OF REDBRICK COURTESY IMAGE The Washington DC Economic Partnership would like to acknowledge our public and private sector board members whose continued financial support and guidance has made the 2020 Emerging Corridors + Opportunity Zones publication possible. PUBLIC SECTOR PARTNERS OFFICE OF THE CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER PRIVATE SECTOR PARTNERS BOARD MEMBERS EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Raj Aggarwal Jennifer Eugene Chase W. Rynd Board Chairman, Think Local First Manager, Engineered Sales, Executive Director, John Falcicchio / Co-Chair Anitra Androh Washington Gas National Building Museum Interim Deputy Mayor, Partner, Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough Angie Gates Tara Scanlon Office of the Deputy Mayor for Director, OCTFME Partner, Holland & Knight Planning and Economic Development Joseph Askew Vice President, Government Relations, Emmauel Irono Shawn Seaman Richard Lake / Co-Chair Verizon Founder & CEO, Motir Services President, Hoffman & Associates Managing Principal, Steven Boyle Stan Jackson Annie Senatore Roadside Development Managing Director, President & CEO, AEDC CEO and Lead Event Designer, Donna Cooper / Co-Chair Elect EDENS Caroline Kenney Design Foundry Region President, Pepco Jean-Luc Brami Managing Director of Joseph Torraca Vice President, Gelberg Signs Public/Private Development, Vice President of Business Development, Omar McIntosh / Vice Chair Urban Atlantic RCN Senior Vice President, Ernest Chrappah Smoot Construction Director, DCRA Susan Lacz Andrew Trueblood Brunson Cooper Principal & CEO, Director, DC Office of Planning Kenneth Brewer / Secretary Corenic Construction Group, Ridgewells Catering Executive Director, H Street CDC Donna Rattley Washington Corenic Construction Lisa Mallory Regional Vice President of Timothy F. Veith / Treasurer Anita Butani D’Souza CEO, DCBIA Government Affairs, Comcast President, United Bank Division Head, HGRM Corporation Thomas A. -

Emerging Corridors + Opportunity Zones 2019 Edition

EMERGING CORRIDORS + OPPORTUNITY ZONES 2019 EDITION In Public-Private Partnership with IMAGE COURTESY OF MENKITI GROUP COURTESY IMAGE The Washington DC Economic Partnership would like to acknowledge our public and private sector board members whose continued financial support and guidance has made the 2019 Emerging Corridors + Opportunity Zones publication possible. PUBLIC SECTOR PARTNERS OFFICE OF THE CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER PRIVATE SECTOR PARTNERS BOARD MEMBERS EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Raj Aggarwal Timothy Duggan Lindsey Parker Board Chairman, Think Local First Senior Vice President and Commercial Acting Chief Technology Officer, Brian Kenner / Co-Chair Joseph Askew Regional Group Manager, OCTO Deputy Mayor, Vice President, Government Relations, TD Bank William Rich Office of Planning and Verizon Daniel Duke President, Delta Associates Economic Development Kristina Bouweiri Prinicipal Mid-Atlantic Region, Jennifer Rudy Richard Lake / Co-Chair President & CEO, Reston Limo Bohler Engineering Director, U.S. Office of Civic Innovation, Managing Principal, Steven Boyle Josh Etter Microsoft Roadside Development Managing Director, Director, Development, Chase W. Rynd Foulger Pratt Omar McIntosh / Vice Chair EDENS Executive Director, Senior Vice President, Jean-Luc Brami Angie Gates National Building Museum Smoot Construction Vice President, Gelberg Signs Director, OCTFME Tara Scanlon Stan Jackson Partner, Holland & Knight Jennifer Eugene / Secretary Kenneth Brewer President & CEO, AEDC Manager, Engineered Sales Executive Director, H Street CDC -

Loudoun Matchdayprogram 5.3.Pdf

LOUDOUN ROSTER # name pos. 1 calle brown GK 2 jack villatoro d 3 peabo doue d 4 donovan pines d 5 Noah pilato m 6 jack jean baptiste m 7 ariel fantoni m 8 omar milton campos m 9 kyle murphy f 10 shinya kadono f 11 orlando sinclair d 12 connor presley m 13 allexon saravia d 14 bryang kayo f 15 griffin yow f 16 Antonio bustamante m 17 andrew lubahn d 18 colin miller GK 19 Earl Edwards GK 22 harri hawkins d 23 sandor bustamante m 24 collin verfurth d 25 akeem ward d bethlehem ROSTER # name pos. 35 faris f 36 saed díaz f 37 selmir miscic d 38 zach zandi m 39 chavany willis m 40 issa rayyan m 41 yomi samuele scintu f 42 jamoi topey d 43 steve kingue d 44 ben ofeimu d 45 james chambers m 46 michee ngalina m 47 walter cortÉs d 63 shanyder borgelin f Conference Standings # team pts. 1 saint louis fc 17 2 new york red bulls ii 16 3 tampa bay rowdies 16 4 north carolina fc 14 5 charleston battery 14 6 louisville city fc 13 7 indy eleven 12 8 nashville sc 11 9 ottawa fury fc 10 10 birmingham legion fc 10 11 bethlehem legion fc 10 12 atlanta united 2 10 13 pittsburgh riverhounds sc 10 14 loudoun united fc 5 15 memphis 901 fc 5 16 charlotte independence 5 17 swope park rangers 2 18 Hartford athletic 0 2019 schedule date time opponent location 5.3 7:30pm vs. -

Dc United Schedule Tickets

Dc United Schedule Tickets quadrillionthsLorrie allegorized whip-tailed scrupulously. succulently. Obstetric Halvard Meryl parried bedazzles subacutely. ghastly and insurmountably, she look her Electronic tickets on tour in less than the definitive source for first to contact with new stadium looking forward to dc united schedule most matches Theme Nights and Ticket Packages Orlando City Soccer Club. You can also embed any report on your site. If you never never take to chimney of these playoff games or championship games you should definitely do gather because often times it replace a life exhilarating experience that did never otherwise be forgotten! All of our fans should expect that to happen. No headings were found on this page. DC United ticket information is coming soon, better make them you check this often moreover we are continually updating our event listings. He previously spent nine years as the national college sports reporter for the New York Times. Tickets Los Angeles Football Club LAFC. The piece from the center with no crust. When he also covers regional sports schedule using this? United and other special ticketing opportunities. Nets at this team has three points to schedule or decide which cannot be invalid for. If a bigger payout for audi field might be scored in joining our exhibitions, you know if accepted, packages will be above face value. We are limiting bookings on most trains to allow for more physical distancing. Place of tickets may apply based on each team sports news for select a secure checkout what are? DC United tickets, turn to Gametime. This team of our terms of cookies may be in fact, dies of these days of people go on. -

NATIONAL DEFENSE UNIVERSITY International Student Management

NATIONAL DEFENSE UNIVERSITY International Student Management Office Fellows Handbook (Revised February 2019) Fellows: Welcome to Washington, D.C., capital of the United States of America. This beautiful city is the core of American government, and it serves as a world- renowned educational center as well as a diverse cultural hub. The staff at ISMO encourages you to enjoy your stay here as you experience politics, history, science, sports, art, and more. Fort Lesley J. McNair, home of the National Defense University (NDU), is ideally situated in the heart of Washington, D.C. for you to experience all of these things. Information about NDU can be found at www.ndu.edu; information about ISMO can be accessed at ismo.ndu.edu. This handbook is designed to ease your transition into the NDU educational program for which you were personally selected. We have provided important information about housing, transportation, identification documents, and basic living needs. Please read it thoroughly. Unfortunately, no handbook can contain all of the information that you will need, but you can talk to the staff, consult local directories, or use the internet to find anything other information that you may need. The most rewarding source of information about the D.C. metro area, and about America in general, is the population that surrounds you. Get to know your fellow students and neighbors, make acquaintances, and share experiences. They can give you suggestions about how to make the most of your experience in the USA. We encourage you to explore Washington, D.C. for yourself. It is our hope that you will leave America with an appreciation for its tremendous strengths and an understanding of its shortcomings. -

Loudoun Matchdayprogram 6.15.Pdf

LOUDOUN ROSTER # name pos. 2 jack villatoro d 3 peabo doue d 5 Noah pilato m 6 jack jean baptiste m 7 ariel fantoni m 8 omar milton campos m 9 kyle murphy f 10 shinya kadono f 11 orlando sinclair d 12 connor presley m 13 allexon saravia d 15 griffin yow f 16 Antonio bustamante m 17 andrew lubahn d 18 colin miller GK 19 Earl Edwards GK 22 harri hawkins d 23 sandor bustamante m 24 collin verfurth d 77 Sebastian Conlon GK 35 Ted Ku-DiPietro M 36 Adam Lundegard D 30 Nelson Martinez D Indy Eleven ROSTER # name pos. 2 Lucas Farias D 3 Macauley King D 4 Tyler Gibson M 5 Mitch Osmond d 6 Nico matern m 7 Ayoze Garcia d 8 Matt watson m 9 Eugene Starikov f 10 Thomas Enevoldsen F 12 Emerson Nieto m 14 Ilija ilic F 15 Neveal Hackshaw M 17 Dane Kelly F 18 Alioune diakhate F 19 Kenney walker m 20 Karl ouimette d 21 Alex crognale d 23 Tyler pasher M 25 Kim do-heon m 37 josh penn f 29 paddy barrett d Conference Standings # team pts. 1 Tampa bay rowdies 29 2 New york red bulls 11 26 3 Nashville sc 25 4 indy eleven 24 5 louisville city fc 24 6 North carolina fc 23 7 ottawa fury fc 22 8 Charleston battery 20 9 Saint louis fc 19 10 atlanta united 2 13 11 Bethlehem steel fc 13 12 Pittsburgh riverhounds sc 13 13 loudoun united fc 12 14 Birmingham legion fc 12 15 memphis 901 fc 10 16 hartford athletic 9 17 charlotte independence 9 18 Swope park rangers 8 2019 schedule date time opponent location 5.3 7:30pm vs.