Raising a Red Card: Why Freddy Adu Should Not Be Allowed to Play Professional Soccer Jenna Merten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

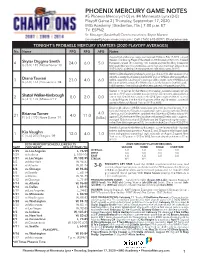

PHOENIX MERCURY GAME NOTES #5 Phoenix Mercury (1-0) Vs

PHOENIX MERCURY GAME NOTES #5 Phoenix Mercury (1-0) vs. #4 Minnesota Lynx (0-0) Playoff Game 2 | Thursday, September 17, 2020 IMG Academy | Bradenton, Fla. | 7:00 p.m. ET TV: ESPN2 Sr. Manager, Basketball Communications: Bryce Marsee [email protected] | Cell: (765) 618-0897 | @brycemarsee TONIGHT'S PROBABLE MERCURY STARTERS (2020 PLAYOFF AVERAGES) No. Name PPG RPG APG Notes Aquired by the Mercury in a sign-and-trade with Dallas on Feb. 12, 2020...named Western Conference Player of the Week on 9/8 for week of 8/31-9/6...finished 4 Skylar Diggins-Smith 24.0 6.0 5.0 the season ranked 7th in scoring, 10th in assists and tied for 4th in three-point G | 5-9 | 145 | Notre Dame '13 field goals (46)...scored a postseason career-high and team-high 24 points on 9/15 vs. WAS...picked up her first playoffs win over Washington on 9/15 WNBA's all-time leader in postseason scoring and ranks 3rd in all-time assists in the playoffs...6 assists shy of passing Sue Bird for 2nd on WNBA's all-time playoffs as- 3 Diana Taurasi 23.0 4.0 6.0 sists list...ranked 5th in the league in scoring and 8th in assists...led the WNBA in 3-pt G | 6-0 | 163 | Connecticut '04 field goals (61) this season, the 11th time she's led the league in 3-pt field goals... holds a perfect 7-0 record in single elimination games in the playoffs since 2016 Started in 10 games for the Mercury this season..scored a career-high 24 points on 9/11 against Seattle in a career-high 35 mimutes...also posted a 2 Shatori Walker-Kimbrough 8.0 2.0 0.0 career-high 5 steals this season in the 8/14 game against Atlanta...scored G | 6-1 | 170 | Missouri '19 in double figures 5 of the final 8 games of the regular season...scored 8 points in Mercury's Round 1 win on 9/15 vs. -

PHILADELPHIA UNION V PORTLAND TIMBERS (Sept

PHILADELPHIA UNION v PORTLAND TIMBERS (Sept. 10, PPL Park, 7:30 p.m. ET) 2011 SEASON RECORDS PROBABLE LINEUPS ROSTERS GP W-L-T PTS GF GA PHILADELPHIA UNION Union 26 8-7-11 35 35 30 1 Faryd Mondragon (GK) at home 13 5-1-7 22 19 15 3 Juan Diego Gonzalez (DF) 18 4 Danny Califf (DF) 5 Carlos Valdes (DF) Timbers 26 9-12-5 32 33 41 MacMath 6 Stefani Miglioranzi (MF) on road 12 1-8-3 6 7 22 7 Brian Carroll (MF) 4 5 8 Roger Torres (MF) LEAGUE HEAD-TO-HEAD 25 Califf Valdes 15 9 Sebastien Le Toux (FW) ALL-TIME: 10 Danny Mwanga (FW) Williams G Farfan Timbers 1 win, 1 goal … 7 11 Freddy Adu (MF) Union 0 wins, 0 goals … Ties 0 12 Levi Houapeu (FW) Carroll 13 Kyle Nakazawa (MF) 14 Amobi Okugo (MF) 2011 (MLS): 22 9 15 Gabriel Farfan (MF) 5/6: POR 1, PHI 0 (Danso 71) 11 16 Veljko Paunovic (FW) Mapp Adu Le Toux 17 Keon Daniel (MF) 18 Zac MacMath (GK) 19 Jack McInerney (FW) 16 10 21 Michael Farfan (MF) 22 Justin Mapp (MF) Paunovic Mwanga 23 Ryan Richter (MF) 24 Thorne Holder (GK) 25 Sheanon Williams (DF) UPCOMING MATCHES 15 33 27 Zach Pfeffer (MF) UNION TIMBERS Perlaza Cooper Sat. Sept. 17 Columbus Fri. Sept. 16 New England PORTLAND TIMBERS Fri. Sept. 23 at Sporting KC Wed. Sept. 21 San Jose 1 Troy Perkins (GK) 2 Kevin Goldthwaite (DF) Thu. Sept. 29 D.C. United Sat. Sept. 24 at New York 11 7 4 Mike Chabala (DF) Sun. -

Special Invitation IMG Academy 2019

IMPORTANT INFORMATION Monday 12th to Sunday 18th August 2019 4 or 8 MATCHES GUARANTEED FOR EVERY PARTICIPANT! * See regulations Organizers: www.ten-pro.net Contact & Registration: [email protected] The venue: www.imgacademy.com Established over 40 years ago as the Bollettieri Tennis Academy, IMG Academy sets the standard by which all tennis academies around the world are measured. Located in Bradenton, FL., IMG Academy is the world's largest multi-sport training and educational institution and has developed 16 ATP/WTA No. 1 players as well as some of the world's top juniors. IMG Academy tennis provides players with the opportunity to train in a global atmosphere with expert coaches who have collegiate and ATP/ WTA/ITF experience. With year-round weekly and multi-week camp programs as well as a 5th-12th grade boarding school, IMG Academy is the optimal setting for athletes to reach their full potential. Learn more about IMG camp and boarding school programs at: www.imgacademy.com TOURNAMENTS INFORMATION! TEN-PRO & IMG ACADEMY invite you to participate at this unique International tennis tournament for worldwide highly talented boys and girls, born in 2004 up to and including 2011. It will be played in six separate competitions in each age category at the same time U10, U11, U12, U13, U14 and U15. This outdoor tournament will be held at IMG ACADEMY Address: 5650 Bollettieri BLVD. Bradenton, Florida,USA WE GUARANTEE EVERY PLAYER 4 OR 8 MATCHES! *see regulations NOTE: Players are guaranteed 4 matches per category or 8 matches for registration in two categories.This request should be send to [email protected] for the attention of Goran Novakovic. -

Faculty of Business Administration and Economics

FACULTY OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION AND ECONOMICS Working Paper Series Working Paper No. 2018-10 THE SUPERSTAR CODE - DECIPHERING KEY CHARACTERISTICS AND THEIR VALUE Franziska Prockl May 2018 THE SUPERSTAR CODE - DECIPHERING KEY CHARACTERISTICS AND THEIR VALUE. Franziska Prockl Paderborn University, Management Department, Chair of Organizational, Media and Sports Economics, Warburger Str. 100, D-33098 Paderborn. May 2018 Working Paper ABSTRACT The purpose of the presented research is to advance the superstar literature on the aspect of superstar’s characteristics and value. Typically, superstar research is faced with one problem: They apply the same criteria to determine who their superstars are as to describe them later because they lack “an objective measure of star quality” (Krueger, 2005, p.18). To avoid this complication, the author chose to study Major League Soccer’s (MLS) designated players as this setting present a unique, as discrete, assignment of star status. MLS has formally introduced stars in 2007 under the designated player (DP) rule which delivers over 100 star-observations in the last ten years to investigate MLS strategy of star employment. The insights from this data set demonstrate which characteristics are relevant, whether MLS stars can be categorized as Rosen or Adler stars, and what the MLS pays for and in this sense values most. A cluster analysis discovers a sub group of ten stars that stand out from the others, in this sense superstars. A two-stage regression model confirms the value stemming from popularity, leadership qualities, previous playing level, age and national team experience but refutes other typical performance indicators like games played and goals scored or position. -

Madrid Close In

PREVIEW ISSUE FOUR – 24TH APRIL 2012 MADRID CLOSE IN REAL TAKE THE SPOILS IN THE EL CLASICO AND CLOSE IN ON THE SILVERWARE After a poor week for both sides in Europe, Real and Barca were desperate to grab a win against their biggest rivals on a dramatic, rain-lashed Saturday night at the Nou Camp. It was Real that grabbed the vital win and probably clinched the La Liga title. Los Merengues went ahead through German midfielders Sami Khedira and were comfortable for long periods, but Barca’s Chilean substitute Alexis Sánchez equalised with just 20 minutes remaining. Cristiano Ronaldo’s clinical strike just three minutes later settled the game with Madrid now seven points clear, with only four games remaining. Madrid coach José Mourinho named an very attacking team and his side began the better. Ronaldo’s early header from a corner brought a superb flying save from goalkeeper Víctor Valdés. His opposite number Iker Casillas was then quickly off his line when full-back Dani Alves dispossessed Sergio Ramos. The game was being played at a fearsome pace and French striker Karim Benzema brought the best out of Valdés again. Barca thought they had gone front when Alves had the ball in the net after a Cristian Tello run, but the youngster had been flagged offside. INSIDE THIS WEEK’S WFW Real’s brave start was rewarded when Pepe’s header from another corner was half- - RESULTS ROUND-UP ON ALL MAJOR stopped by Valdes and Khedira tackled an COMPETITIONS FROM AROUND THE hesitant Carles Puyol to push the ball into the WORLD net to put Madrid ahead. -

Onside: a Reconsideration of Soccer's Cultural Future in the United States

1 ONSIDE: A RECONSIDERATION OF SOCCER’S CULTURAL FUTURE IN THE UNITED STATES Samuel R. Dockery TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin May 8, 2020 ___________________________________________ Matthew T. Bowers, Ph.D. Department of Kinesiology Supervising Professor ___________________________________________ Elizabeth L. Keating, Ph.D. Department of Anthropology Second Reader 2 ABSTRACT Author: Samuel Reed Dockery Title: Onside: A Reconsideration of Soccer’s Cultural Future in the United States Supervising Professors: Matthew T. Bowers, Ph.D. Department of Kinesiology Elizabeth L. Keating, Ph.D. Department of Anthropology Throughout the course of the 20th century, professional sports have evolved to become a predominant aspect of many societies’ popular cultures. Though sports and related physical activities had existed long before 1900, the advent of industrial economies, specifically growing middle classes and ever-improving methods of communication in countries worldwide, have allowed sports to be played and followed by more people than ever before. As a result, certain games have captured the hearts and minds of so many people in such a way that a culture of following the particular sport has begun to be emphasized over the act of actually doing or performing the sport. One needs to look no further than the hours of football talk shows scheduled weekly on ESPN or the myriad of analytical articles published online and in newspapers daily for evidence of how following and talking about sports has taken on cultural priority over actually playing the sport. Defined as “hegemonic sports cultures” by University of Michigan sociologists Andrei Markovits and Steven Hellerman, these sports are the ones who dominate “a country’s emotional attachments rather than merely representing its callisthenic activities.” Soccer is the world’s game. -

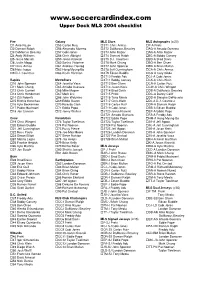

Upper Deck Major League MLS 2004

www.soccercardindex.com Upper Deck MLS 2004 checklist Fire Galaxy MLS Stars MLS Autographs (x/20) 1 Ante Razov 55 Carlos Ruiz ST1 Chris Armas P-A Preki 2 Damani Ralph 56 Alejandro Moreno ST2 DaMarcus Beasley AG-A Amado Guevara 3 DaMarcus Beasley 57 Cobi Jones ST3 Ante Razov AR-A Ante Razov 4 Andy Williams 58 Chris Albright ST4 Damani Ralph BC-A Bobby Convey 5 Jesse Marsch 59 Jovan Kirovski ST5 D.J. Countess BD-A Brad Davis 6 Justin Mapp 60 Sasha Victorine ST6 Mark Chung BO-A Ben Olsen 7 Chris Armas 61 Andreas Herzog ST7 John Spencer BR-A Brian Mullan 8 Nate Jaqua 62 Hong Myung-Bo ST8 Jeff Cunningham CA-A Chris Armas 9 D.J. Countess 63 Kevin Hartman ST9 Edson Buddle CG-A Cory Gibbs ST10 Freddy Adu CJ-A Cobi Jones Rapids MetroStars ST11 Bobby Convey CK-A Chris Klein 10 John Spencer 64 Joselito Vaca ST12 Ben Olsen CR-A Carlos Ruiz 11 Mark Chung 65 Amado Guevara ST13 Jason Kreis CW-A Chris Wingert 12 Chris Carrieri 66 Mike Magee ST14 Brad Davis DB-A DaMarcus Beasley 13 Chris Henderson 67 Mark Lisi ST15 Preki DC-A Danny Califf 14 Zizi Roberts 68 John Wolyniec ST16 Tony Meola DD-A Dwayne DeRosario 15 Ritchie Kotschau 69 Eddie Gaven ST17 Chris Klein DJ-A D.J. Countess 16 Kyle Beckerman 70 Ricardo Clark ST18 Carlos Ruiz DR-A Damani Ralph 17 Pablo Mastroeni 71 Eddie Pope ST19 Cobi Jones EB-A Edson Buddle 18 Joe Cannon 72 Jonny Walker ST20 Jovan Kirovski EP-A Eddie Pope ST21 Amado Guevara FA-A Freddy Adu Crew Revolution ST22 Eddie Pope HM-A Hong Myung-Bo 19 Chris Wingert 73 Taylor Twellman ST23 Taylor Twellman JA-A Jeff Agoos 20 Edson Buddle 74 -

James Bollettieri Has Tennis in His Blood. While He's the Son of Famed

James Bollettieri has tennis in his blood. While he’s the son of famed coach Nick Bollettieri —founder of the IMG Academy, which developed stars like Anna Kournikova and Andre Agassi —Bollettieri has staked his own claim as an elite coach over a career spanning 45 years. Bollettieri, 65, doesn’t think of tennis as merely a sport, but part of a varied “lifestyle” that encompasses art, photography, his love of surfing, and the outdoors. It’s all part of a whole that defines who he is. Some of Bollettieri’s earliest memories of tennis stretch back to being four years old and on the court beside his dad up to his young adult years traveling the country, initially observing his father and later mentoring and shaping tennis greats himself. Bollettieri says he started coaching at just 15, working during the summers at his father’s camp, filling in wherever he was needed. “It started out with ‘son, go down there and take care of that section of mainly adult women,’ helping out wherever there was a need, which eventually grew to running camps, which is a big responsibility,” Bollettieri says. That dovetailed with his burgeoning interest in photography, which began when he was in the ninth grade. He would go on to earn his Bachelor of Arts in photography from the University of Miami. Bollettieri has photographed the likes of John McEnroe and Roger Federer, his work appearing everywhere from ESPN and art galleries to the walls of tennis clubs around the country and the U.S. Open. “I would say it’s the depth of the photo that makes a good one. -

Upper Deck Major League MLS 2005

www.soccercardindex.com Upper Deck MLS 2005 checklist Fire Revolution MLS Goal Men MLSignatures (x/25) 1 Tony Sanneh 59 Pat Noonan GM1 Justin Mapp AE-S Alecko Eskandarian 2 Ante Razov (Crew) 60 Taylor Twellman GM2 Joe Cannon AG-S Amado Guevara 3 Andy Herron 61 Steve Ralston GM3 Edson Buddle AR-S Ante Razov 4 Chris Armas 62 Andy Dorman GM4 Jon Busch BC-S Brian Ching 5 Kelly Gray 63 Jose Cancela GM5 Eddie Johnson BM-S Brian Mullan 6 Nate Jaqua 64 Clint Dempsey GM6 Freddy Adu CA-S Chris Armas 7 Justin Mapp 65 Matt Reis GM7 Jaime Moreno CD-S Clint Dempsey 66 Jay Heaps GM8 Josh Wolff CJ-S Cobi Jones Rapids GM9 Nick Rimando CR-S Carlos Ruiz 8 Joe Cannon Earthquakes GM10 Davy Arnaud DA-S Davy Arnaud 9 Pablo Mastroeni 67 Craig Waibel GM11 Carlos Ruiz DK-S Dema Kovalenko 10 Landon Donovan (Galaxy) 68 Ryan Cochrane GM12 Amado Guevara EB-S Edson Buddle 11 Jean Philippe Peguero 69 Pat Onstad GM13 Pat Noonan EG-S Eddie Gaven 12 Mark Chung 70 Brian Ching GM14 Taylor Twellman EP-S Eddie Pope 13 Jordan Cila 71 Brian Mullan GM15 Pat Onstad FA-S Freddy Adu 14 Chris Henderson 72 Dwayne De Rosario GM16 Brian Ching JA-S Jonny Walker 73 Troy Dayak GM17 Ante Razov JB-S Jon Busch Crew 74 Eddie Robinson GM18 Jeff Cunningham JC-S Joe Cannon 15 Edson Buddle JG-S Jeff Agoos 16 Jon Busch CD Chivas USA MLS Jersey JK-S Jason Kreis 17 Jeff Cunningham (Rapids) 75 Arturo Torres BC-J Brian Ching JM-S Justin Mapp 18 Ross Paule 76 Orlando Perez CA-J Chris Armas JO-S Jaime Moreno 19 Klye Martino 77 Ezra Hendrickson CR-J Carlos Ruiz JP-S Jean Philippe Peguero 20 Simon Elliott -

Media Kit March 2021

MEDIA KIT MARCH 2021 ABOUT IMG ACADEMY IMG Academy is one of the world’s most prestigious sports, performance and educational institutions. Established in 1978 with a pioneering concept known as the Nick Bollettieri Tennis Academy, IMG Academy has since grown to become a global phenomenon. With our world-renowned boarding school and noted sports camps, IMG continues to set the standard for total academic, athletic and personal development in youth student-athletes. The 600-acre, Bradenton, Florida campus annually attracts hundreds of teams, groups and events for training and competition. Pro, Olympic and collegiate athletes leverage cutting-edge sport science to gain a greater edge on the competition. Adult athletes turn back the clock with sport instruction that hones their game, then unwind in a setting of contemporary luxury in the Legacy Hotel at IMG Academy. Corporate professionals become better leaders, teammates and communicators with our dynamic retreats and IMG Institute programming. As we continue to grow campus and refine our developmental methodology, our goal remains steadfast: Help the most dedicated and passionate maximize their inherent potential. KEY FACTS • Sport programs offered: Tennis (launched 1978), Golf (1993), Soccer (1994), Baseball (1994), Basketball (2001), Football (2010), Lacrosse (2010), Track & Field and Cross Country (2013) • Boarding school: { 1,200+ student-athletes (Grade 6-12 and Post-Graduate) hailing from 49 U.S. states and 60+ countries in the 2020-2021 student body { Methodology that balances academics, -

Chapter 5. the Integration of Youth Soccer

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Fútbol Americano : Immigration, Social Capital, and Youth Soccer in Southern California Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4436w58z Author Keyes, David Gordon Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Fútbol Americano: Immigration, Social Capital, and Youth Soccer in Southern California A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by David Gordon Keyes Committee in charge: Professor David Pedersen, Chair Professor Wayne Cornelius Professor Robert Edelman Professor Joseph Hankins Professor Nancy Postero 2015 © David Gordon Keyes, 2015 All rights reserved Signature Page The dissertation of David Gordon Keyes is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2015 iii Table of Contents Signature Page ............................................................................................. iii Table of Contents ......................................................................................... iv List of Figures .............................................................................................. vi Vita ............................................................................................................... vii Abstract of the Dissertation -

Major League Soccer As a Case Study in Complexity Theory

Florida State University Law Review Volume 44 Issue 2 Winter 2017 Article 1 Winter 2017 Major League Soccer as a Case Study in Complexity Theory Steven A. Bank UCLA School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Contracts Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation Steven A. Bank, Major League Soccer as a Case Study in Complexity Theory, 44 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 385 (2018) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol44/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAJOR LEAGUE SOCCER AS A CASE STUDY IN COMPLEXITY THEORY STEVEN A. BANK* ABSTRACT Major League Soccer has long been criticized for its “Byzantine” roster rules and regu- lations, rivaled only by the Internal Revenue Code in its complexity. Is this criticism fair? By delving into complexity theory and the unique nature of the league, this Article argues that the traditional complaints may not apply in the context of the league’s roster rules. Effectively, critics are applying the standard used to evaluate the legal complexity found in rules such as statutes and regulations when the standard used to evaluate contractual complexity is more appropriate. Major League Soccer’s system of roster rules is the product of a contractual and organizational arrangement among the investor-operators.