Venue Management Rob Ammon—Slippery Rock University Editorial Review Board Members: University of South Carolina Peter J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Program 2020

FOOTBALL PROGRAM 2020 20 19 92nd SEASON OF Wesgroup is a proud supporter of Vancouver College’s Fighting Irish Football Team. FOOTBALL 5400 Cartier Street, Vancouver BC V6M 3A5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Principal’s Message ...............................................................2 Irish Football Team Awards 1941-2019 ..............................19 Head Coach’s Message .........................................................2 Irish Records 1986-2019 ......................................................22 Vancouver College Staff and Schedules 2020 .......................3 Irish Provincial Championship Game 2020 Fighting Irish Coaches and Supporting Staff ................4 Award Winners 1966-2018 .................................................29 Irish Alumni Currently Playing in the CFL and NFL ................5 Back in the Day ....................................................................29 2020 Fighting Irish Graduating Seniors .................................6 Irish Cumulative Record Against Opponents 1929-2018 .....30 Fighting Irish Varsity Statistical Leaders 2019 ......................8 Fighting Irish Varsity Football Team 2019 ...........................34 Vancouver College Football Awards 2019 .............................9 Irish Statistics 1996-2018 ...................................................35 Irish Varsity Football Academic Awards ...............................10 Archbishops’ Trophy Series 1957-2018 .............................38 Irish Academics 2020 ..........................................................10 -

Chicago White Sox James Pokrywczynski Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette College of Communication Faculty Research and Communication, College of Publications 1-1-2011 Chicago White Sox James Pokrywczynski Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. "Chicago White Sox," in Encyclopedia of Sports Management and Marketing. Eds. Linda E. Swayne and Mark Dodds. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2011: 213-214. Publisher Link. © 2011 Sage Publications. Used with permission. Chicago White Sox 213 Chicago White Sox The Chicago White Sox professional baseball fran- chise has constantly battled for respect and attention since arriving in Chicago in 1901. Some of the lack of respect has been self-inflicted, coming from stunts such as uniforms with short pants, or a disco record demolition promotion that resulted in a forfeiture of a ballgame, one of the few in baseball history. The other source of disrespect comes from being in the same market with the Chicago Cubs, which has devel- oped an elite and special image in the minds of many despite having the longest championship drought in professional sports history. The past 20 years have featured an uptick in the franchise’s reputation, with the opening of a new ballpark (called U.S. Cellular Field since 2003) that seats 40,000 plus, and a World Series championship in 2005. The franchise began in 1901 when Charles Comiskey moved his team, the St. Paul Saints, to Chicago to compete in a larger market. Comiskey soon built a ballpark on the south side of town, named it after himself, and won two champion- ships, the last under his ownership in 1917. -

Mls Cup Ticket Giveaway Official Rules No

MLS CUP TICKET GIVEAWAY OFFICIAL RULES NO PURCHASE NECESSARY TO ENTER. OPEN TO LEGAL RESIDENTS OF THE UNITED STATES (EXCLUDING RESIDENTS OF RHODE ISLAND, PUERTO RICO, THE U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS, AND OTHER COMMONWEALTHS, TERRITORIES AND POSSESSIONS AND WHERE OTHERWISE PROHIBITED BY LAW), WHO HAVE REACHED 18 YEARS OF AGE NO LATER THAN NOVEMBER 1, 2016. 1. By entering this CONTEST (the "Contest") and accepting the terms herein, you agree to be bound by the following rules ("Official Rules"), which constitute a binding agreement between you, on one hand, and SeatGeek, Inc., on the other (“SeatGeek”). SeatGeek and any website companies hosting and promoting the Contest, their respective parent companies, affiliates, subsidiaries, advertising and promotion agencies, and all of their agents, officers, directors, shareholders, employees, and agents are referred to as the Contest Entities. These Official Rules apply only to the Contest and not to any other sweepstakes or contest sponsored by SeatGeek. 2. CONTEST DETAILS: SeatGeek shall give away, for no consideration, 4 VIP ticket packages for the 2016 MLS Cup. The Contest will be promoted by SeatGeek during November and December 2016. 3. ELIGIBILITY: This Contest is open only to legal residents of the United States (excluding residents of Rhode Island, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and other commonwealths, territories and possessions, and where otherwise prohibited by law) who have reached 18 YEARS OF AGE no later than November 1, 2016 ("Entrants"). Individuals in any of the following categories are not eligible to enter or win this Contest: (a) employees of SeatGeek or their affiliates, parents, subsidiaries, professional advisors and promotional agencies or other entities involved in the sweepstakes; and (b) individuals who are immediate family members or who reside in the same household as any individual described above. -

Vancouver Whitecaps FC BC REX Program

British Columbia Soccer Association Suite 250 – 3410 Lougheed Highway, Vancouver, BC V5M 2A4 Phone: 604-299-6401 Fax: 604-299-9610 Website: www.bcsoccer.net BC Soccer High Performance Annual Plan- 2017 Phase One 2017 BC Soccer facilitated Match Schedule - Male Development Pathway BC Soccer High Performance Program BC Soccer High Performance Program matches to be integrated with the Vancouver Whitecaps FC BC REX Program. Schedule Vancouver Whitecaps FC Residency U15 (2002) # Date Team Level - Age Location/Time 1. Tuesday 28 Feb BC Soccer BC HPP (2002/2001) SFU Field 4 4:30pm K/O 2. Tuesday 28 Mar BC Soccer BC HPP (2002/2001) 3. Tuesday 25 Apr BC Soccer BC HPP (2002/2001) 4. Tuesday 6 June BC Soccer BC HPP (2002/2001) Vancouver Whitecaps FC Residency U14 (2003) # Date Team Level - Age Location/Time 1. Tuesday 28 Feb BC Soccer BC HPP (2003/2002) SFU Field 4 6:00pm K/O 2. Tuesday 28 Mar BC Soccer BC HPP (2003/2002) 3. Tuesday 25 Apr BC Soccer BC HPP (2003/2002) 4. Tuesday 6 June BC Soccer BC HPP (2003/2002) Vancouver Whitecaps FC Residency U16 (2000/01) # Date Team Level - Age Location/Time 1. Tuesday 4 Apr BC Soccer BC HPP M (1999/2000) SFU Field 4 430pm K/O 2. Tuesday 16 May BC Soccer BC HPP M (1999/2000) 3. Tuesday 13 June BC Soccer BC HPP M (1999/2000) BC Soccer U17/U18 Canada Games/Showcase Matches # Date Team Level - Age Location/Time 1. Wednesday 22 Feb BC Soccer BC HPP M (1999/2000) Empire Field 2pm K/O 2. -

Conference Brochure Confirmed Speakers

CONFERENCE BROCHURE CONFIRMED SPEAKERS GIANNI INFANTINO DAVID DEIN MBE VICTOR MONTAGLIANI DATO’ WINDSOR JOHN PRESIDENT AMBASSADOR - THE FA & PREMIER PRESIDENT GENERAL SECRETARY FIFA LEAGUE CONCACAF ASIAN FOOTBALL CONFEDERATION LISA BAIRD JAKE EDWARDS JOHN BARNES MBE PHILIPPE MOGGIO COMMISSIONER PRESIDENT FORMER INTERNATIONAL & MANAGER GENERAL SECRETARY NWSL UNITED SOCCER LEAGUE SPORTS COMMENTATOR CONCACAF JOSEPH DAGROSA JR DIDAC LEE YON DE LUISA LUDOVICA MANTOVANI CHAIRMAN BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEMBER PRESIDENT PRESIDENT - WOMEN’S FOOTBALL KAPITAL FOOTBALL GROUP FC BARCELONA MEXICAN FOOTBALL FEDERATION ITALIAN FOOTBALL FEDERATION (FIGC) RONAN JOYCE TOMOS GRACE PATRICK SCHMIDIGER HEIDI PELLERANO LEAD - EMEA sports TEAM HEAD OF SPORT SENIOR LEGAL COUNSEL CHIEF COMMERCIAL OFFICER partnerships YOUTUBE FIFA CONCACAF facebooK HUGO VARELA MONCHI SEBASTIÁN LANCESTREMÈRE JULIANO BELLETTI SENIOR PARTNER SPORT MANAGING DIRECTOR Sports Industry MANAGING DIRECTOR FORMER INTERNATIONAL PLAYER KAPITAL FOOTBALL GROUP SEVILLA FC MICROSOFT CORP JENNIFER valentine RAMON ALARCON RUBIALES SENIOR DIRECTOR - SOCCER, NORTH KARINA LEBLANC CBO & MEMBER OF THE BOARD OF COURT JESKE AMERICA HEAD OF WOMEN’S FOOTBALL DIRECTORS EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT ADIDAS CONCACAF REAL BETIS BALOMPIE UNITED SOCCER LEAGUE SEAN BAI AMANDA DUFFY JAMES KIRKHAM GERARD HOULLIER GENERAL MANAGER - ACADEMY EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT CHIEF BUSINESS OFFICER SOCCER MANAGER VALENCIA CF ORLANDO PRIDE DEFECTED RECORDS RED BULL company JOYCE COOK CHIEF SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY & CHRISTIAN LAU JAKE DAVIS -

1 in the United States District Court for the Western

Case 3:15-cv-00181-KC Document 105 Filed 09/02/15 Page 1 of 38 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS EL PASO DIVISION JORGE CARLOS VERGARA § MADRIGAL, § § Plaintiff/Petitioner, § § v. § EP-15-CV-181-KC § ANGELICA FUENTES TELLEZ, § § Defendant/Respondent. § ORDER On this day, the Court considered Jorge Carlos Vergara Madrigal’s First Amended Verified Petition for Return of Children Under the Hague Convention (the “Amended Petition”), ECF No. 58, in the above-captioned case (the “Case”). By the Amended Petition, Vergara alleges that his wife, Angélica Fuentes Téllez (“Fuentes”), wrongfully removed his two minor children, V.V.F. and M.I.V.F. (collectively, the “Children”) from Mexico and retained them in the United States without his consent. See Am. Pet. 1.1 In accordance with the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction (“Convention” or “Hague Convention”), Vergara seeks the Children’s return to their country of habitual residence in Mexico. Id. at 11. The Case has been a troubling one for this Court. In short, the evidence introduced by the parties causes the Court to wonder whether Vergara cares more about gaining a strategic advantage over his wife in their ongoing divorce proceedings than he does about the happiness 1 When citing to documents that actually appear on the Court’s docket, the Court refers to the pagination assigned by the Court’s electronic docketing system unless otherwise indicated. 1 Case 3:15-cv-00181-KC Document 105 Filed 09/02/15 Page 2 of 38 and well-being of his Children. -

MLS Game Guide

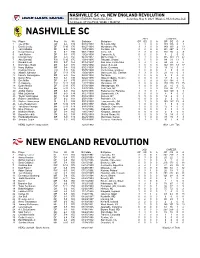

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

Download This Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 8, 2019 CONTACT: Mayor’s Press Office 312.744.3334 [email protected] MAYOR LIGHTFOOT, THE CHICAGO PARK DISTRICT AND CHICAGO FIRE SOCCER CLUB ANNOUNCE THE TEAM’S RETURN TO SOLDIER FIELD The Fire to Return to Soldier Field starting in March 2020 CHICAGO – Mayor Lori E. Lightfoot, Chicago Park District Superintendent & CEO Mike Kelly, and the Chicago Fire Soccer Club today announced that the team will return to Soldier Field to play their home games starting in 2020. SeatGeek Stadium in Bridgeview, Illinois has been home to the Fire since 2006, and the team will continue to utilize the stadium as a training facility and headquarters for Chicago Fire Youth development programs. “Chicago is the greatest sports town in the world, and I am thrilled to welcome the Chicago Fire back home to Solider Field, giving families in every one of our neighborhoods a chance to cheer for their team in the heart of our beautiful downtown,” said Mayor Lori E. Lightfoot. “From arts, culture, business, sports, and entertainment, Chicago is second to none in creating a dynamic destination for residents and visitors alike, and I look forward to many years of exciting Chicago Fire soccer to come.” The Chicago Fire was founded in 1997 and began playing in Major League Soccer in 1998. The Fire won the MLS Cup and the Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup its first season, and additional U.S. Open Cups in 2000, 2003, and 2006. As an early MLS expansion team, the Fire played at Soldier Field from 1998 until 2001 and then from 2003 to 2005 before moving to Bridgeview in 2006. -

LA Galaxy II Will Hit the Road When They Take on Southern California Counterparts Orange County SC on Saturday at 7 P.M

2021 USL Championship LA Galaxy II vs. Orange County SC Overall : 2-2-2 Location: OC Great Park Overall: 1-1-0 GD: +5 Saturday, May 29 GD: 0 Form (last 5): WDWDL Kickoff: 7 p.m. Form: WL BROADCAST: ESPN+ MATCH PREVIEW: LA Galaxy II will hit the road when they take on Southern California counterparts Orange County SC on Saturday at 7 p.m. PT at OC Great Park (ESPN+). LA Galaxy II enter the match having just lost one of their previous five contests. This year, Los Dos are 2-2-2 with eight points, with 11 goals scored and six conceded for a +5 goal differential. In their last match, LA Galaxy II fell to Oakland Roots at Dignity Health Sports Park on Sunday evening. LA Galaxy II featured three first-team players in the starting XI on Wednesday evening: Eric Lopez, Augustine Williams and Kai Koreniuk. Midfielder Axel Picazo scored his first goal as a member of LA Galaxy II. Saturday marks the first contest of the year between LA Galaxy II and Orange County SC. All time, LA Galaxy II are 12-8-4 against OCSC. In their most recent contest, LA Galaxy II earned a 3-1 win over OCSC on Sept. 30, 2020 at Dignity Health Sports Park. In 2020, Los Dos finished the regular season 8-6-2 with 26 points (4-3-1 at home and 4-3-1 on the road), earning them second place in Group B standings and clinching a berth in the USL Championship Playoffs for the second-straight season. -

Ucla World Cup Players 2006

UCLA’S NATIONAL TEAM CONNECTION Snitko competed for the United States in Atlanta, and the 1992 Olympic team UCLA WORLD CUP PLAYERS 2006 ........Carlos Bocanegra included six former Bruins ̶ Friedel, ........................Jimmy Conrad Henderson, Jones, Lapper, Moore and ............................ Eddie Lewis Zak Ibsen ̶ on its roster, the most .............Frankie Hejduk (inj.) from any collegiate institution. Other 2002 ..................Brad Friedel UCLA Olympians include Caligiuri, ...................... Frankie Hejduk .............................. Cobi Jones Krumpe and Vanole (1988) and Jeff ............................ Eddie Lewis Hooker (1984). ......................Joe-Max Moore Several Bruins were instrumental to 1998 ..................Brad Friedel ...................... Frankie Hejduk the United States’ gold medal win .............................. Cobi Jones at the 1991 Pan American Games. ......................Joe-Max Moore Friedel tended goal for the U.S., while 1994 ................Paul Caligiuri Moore nailed the game-winning goal ............................Brad Friedel in overtime in the gold-medal match .............................. Cobi Jones against Mexico. Jones scored one goal ........................... Mike Lapper ......................Joe-Max Moore Bruins Pete Vagenas, Ryan Futagaki, Carlos Bocanegra, Sasha and an assist against Canada. A Bruin- Victorine and Steve Shak (clockwise from top left) won bronze 1990 ................Paul Caligiuri dominated U.S. team won a bronze medals for the U.S. at the 1999 Pan -

PHILADELPHIA UNION V PORTLAND TIMBERS (Sept

PHILADELPHIA UNION v PORTLAND TIMBERS (Sept. 10, PPL Park, 7:30 p.m. ET) 2011 SEASON RECORDS PROBABLE LINEUPS ROSTERS GP W-L-T PTS GF GA PHILADELPHIA UNION Union 26 8-7-11 35 35 30 1 Faryd Mondragon (GK) at home 13 5-1-7 22 19 15 3 Juan Diego Gonzalez (DF) 18 4 Danny Califf (DF) 5 Carlos Valdes (DF) Timbers 26 9-12-5 32 33 41 MacMath 6 Stefani Miglioranzi (MF) on road 12 1-8-3 6 7 22 7 Brian Carroll (MF) 4 5 8 Roger Torres (MF) LEAGUE HEAD-TO-HEAD 25 Califf Valdes 15 9 Sebastien Le Toux (FW) ALL-TIME: 10 Danny Mwanga (FW) Williams G Farfan Timbers 1 win, 1 goal … 7 11 Freddy Adu (MF) Union 0 wins, 0 goals … Ties 0 12 Levi Houapeu (FW) Carroll 13 Kyle Nakazawa (MF) 14 Amobi Okugo (MF) 2011 (MLS): 22 9 15 Gabriel Farfan (MF) 5/6: POR 1, PHI 0 (Danso 71) 11 16 Veljko Paunovic (FW) Mapp Adu Le Toux 17 Keon Daniel (MF) 18 Zac MacMath (GK) 19 Jack McInerney (FW) 16 10 21 Michael Farfan (MF) 22 Justin Mapp (MF) Paunovic Mwanga 23 Ryan Richter (MF) 24 Thorne Holder (GK) 25 Sheanon Williams (DF) UPCOMING MATCHES 15 33 27 Zach Pfeffer (MF) UNION TIMBERS Perlaza Cooper Sat. Sept. 17 Columbus Fri. Sept. 16 New England PORTLAND TIMBERS Fri. Sept. 23 at Sporting KC Wed. Sept. 21 San Jose 1 Troy Perkins (GK) 2 Kevin Goldthwaite (DF) Thu. Sept. 29 D.C. United Sat. Sept. 24 at New York 11 7 4 Mike Chabala (DF) Sun. -

The Marquee Effect : a Study of the Effect of Designated Players On

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 2016 The aM rquee effect : a study of the effect of designated players on revenue and performance in major league soccer Hannah Holub Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Part of the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Holub, Hannah, "The aM rquee effect : a study of the effect of designated players on revenue and performance in major league soccer" (2016). Honors Theses. Paper 849. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Marquee Effect: A Study of the Effect of Designated Players on Revenue and Performance in Major League Soccer by Hannah Holub Honors Thesis Submitted to Department of Economics University of Richmond Richmond, VA April 28, 2016 Advisor: Dr. Jim Monks 1 Table of Contents I. Introduction 3 II. Literature Review 7 III. Theoretical Model 12 IV. Econometric Models and Methods 16 V. Data 22 VI. Results 23 VII. Robustness 28 VIII. Conclusion 31 IX. Appendix 34 X. References 50 2 Introduction Since its formation in 1994 Major League Soccer (MLS) has slowly been gaining the momentum to reach a level of recognition similar to that of the top four sports leagues in the United States – the National Football League, the National Basketball Association, the National Hockey League, and Major League Baseball. Major League Soccer (MLS) is the top tier professional soccer league in the United States, one of only two leagues to reach that status and the only soccer league to sustain long term success.1 Made up of nineteen teams across the United States and Canada, the MLS is structured much differently than the other leagues both within the United States and internationally.